Welcome to the first weekly economic update of 2026.

It has been a turbulent start to the year.

AUS operation to remove Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro earlier this month was followed by public musings from Washington about the possibility of further interventions in Cuba, Colombia, Mexico...and Greenland. Despite the drama, this first exercise of the ‘Donroe Doctrine’ left markets largely unmoved. But for Australia, a new era of militarised resource competition and great power spheres of influence makes foran uncomfortable prospect.

Growing public unrest in Iran has been associated with mounting violence, leading to speculation about possible US military intervention. While global oil markets mostly shrugged off the implications of the Venezuelan adventure, with world excess supply relative to demand continuing to dominate near-term market dynamics, the deteriorating security situation in the Gulf has injected a new element of volatility into oil prices.

Meanwhile, the ongoing confrontation between the White House and the US Federal Reserve has intensified. The Department of Justice has issued the Fed Chair with subpoenas. In response, Jerome Powell finally went on the offensive, declaring that monetary policy was being subject to political pressure. Financial markets did notice this latest crack in the edifice of central bank independence – gold and silver set new record highs, and the US dollar weakened a little – but once again markets have so far remained relatively sanguine. Undue complacency, faith in the durability of Fed independence, or just a recognition that fiscal dominance was already our new reality?

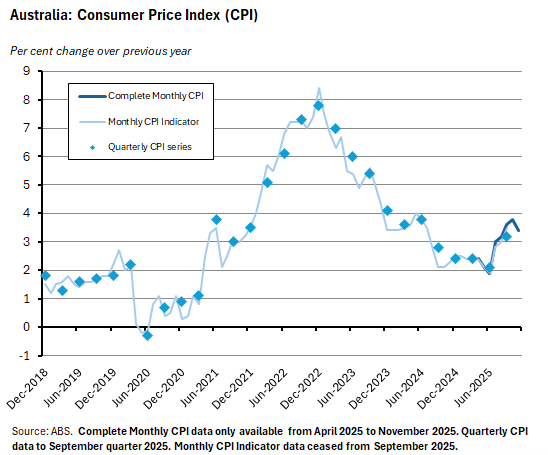

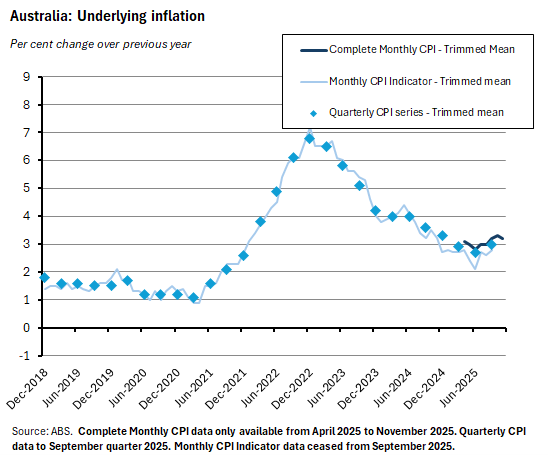

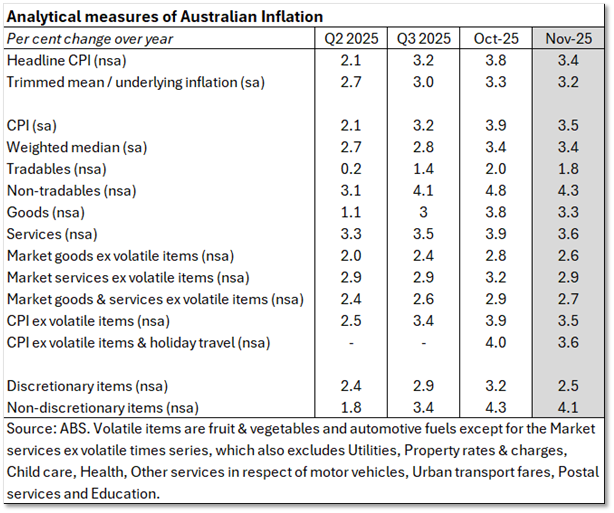

Finally, on the domestic data front, the main economic news since the Christmas break has been the November 2025 inflation reading. This showed a degree of moderation relative to the October 2025 result. The headline rate of CPI inflation fell from 3.8 per cent to 3.4 per cent while underlying inflation eased from 3.3 per cent to 3.2 per cent. But with both rates still running above the top of the RBA's inflation target band, the Monetary Policy Board (MPB) is likely to debate the case for a rate increase at its upcoming meeting on 2-3 February.

Markets currently think there is roughly a 1-in-3 chance of the MPB delivering a rate hike next month, but the Board is yet to be influenced by the December 2025 monthly Labour Force report (due 22 January) and the December 2025 quarterly and monthly inflation readings (due 28 January).

More detail below along with the usual roundup of other Australian data releases and a selection of related further reading and listening.

Iran and the oil market

At the time of hitting ‘send’ on the draft version of this week’s economic update, the outlook for developments in Iran remained unclear. Press reports began the day highlighting the news that the United States had evacuated some personnel from an airbase in Qatar, which was interpreted as clearing the way for impending US military strikes after President Trump had told Iranian protesters on Tuesday this week that ‘help is on its way.’ But subsequent media reports then suggested that an attack was not imminent, after the US President cited assurances from Tehran on the treatment of protesters. Other reports pointed to the operational limitations imposed by recent US military activities in the Caribbean.

In terms of the potential international economic impact of these developments, one obvious place to start is with the oil market. When we looked at oil price risk back in June last year in the context of the conflict between Israel and Iran, the message then was that the historical record told us that regional conflicts have all been associated with varying degrees of disruption to the global oil market. But the historical record also displays no simple, mechanical relationship between oil supply shocks and global economic outcomes. That is because economic outcomes are also usually heavily influenced by the prevailing mix of broader demand and supply side factors.

Since much of that analysis still holds, we won’t repeat it all here. However, given the importance of demand and supply factors in the oil market, it is worth updating last year’s take with the IEA’s December 2025 assessment of the oil market.

According to the IEA, the world economy was enjoying a global oil surplus at the end of 2025, with observed global oil stocks having risen by around 1.3 million barrels per day on average between January and November last year and global observed inventories reaching four-year highs in October. The IEA’s own oil balance analysis implied an even larger stock build of closer to two million barrels per day over the first three quarters of 2025. Looking ahead, the IEA forecasts world oil demand to rise by 860,000 barrels per day this year while global oil supply is projected to increase by a larger 2.4 million barrels per day, increasing the net supply surplus (note that the IEA’s January 2026 oil market report will be published on the 21st of this month).

Venezuela, the ‘Donroe Doctrine’ and resource security

A second major geopolitical flashpoint this month was the US intervention in Venezuela. On 3 January 2026, US forces seized Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro in a successful pre-dawn raid. In the aftermath of Operation Absolute Resolve, various senior voices in Washington speculated about further operations in the Western Hemisphere, from Colombia to Cuba and beyond. Theregime in Havana is seen as particularly vulnerable.

While there have been multiple – and sometimes contradictory – takes on the drivers and implications of the Maduro operation, two theories have tended to dominate.

First, this is widely seen as the first major implementation of the so-called ‘Donroe Doctrine’ (earlier, smaller measures included strikes on boats in the Caribbean and the seizure of Venezuelan oil tankers). This relates to the new US National Security Strategy and its introduction of the ‘Trump Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine’, which declares that Washington will now seek to ‘reassert and enforce the Monroe Doctrine to restore American pre eminence in the Western Hemisphere…We will deny non-Hemispheric competitors the ability to position forces or other threatening capabilities, or to own or control strategically vital assets, in our Hemisphere (p.15).’

This interpretation also seemed to fit with subsequent mentions of additional White House regional ambitions, including Greenland. And it is also consistent with the propositionthat we are moving into a world order characterised by ‘spheres of influence’ for the major powers.

Second, observers have also highlighted President Trump’s comments regarding Venezuela’s oil in the context of the country’s vast reserves to argue that there is a resource security / oil market strategy in play here. Proponents of this view point to Trump’s long-term interest (since at least the 1980s) in securing US control over energy markets, his claims that the United States will take 30 million to 50 million barrels of Venezuelan crude, and declared plans to exert US control over Venezuela’s national oil company Petroleos de Venezuela SA, more commonly known as PDVSA.

In this view of the world, not only is Washington now reasserting the former commercial rights of US oil companies that lost assets to previous rounds of nationalisation, but is seeking to take effective control of the world’s largest oil reserves (more than 300 billion barrels or around 17 per cent of the world total, although some argue these figures are overstated). Combine this with the United States’ status as the world’s largest oil producer, add the dominance of large US oil companies in Guyana, and on some estimates the US would then oversee about 30 per cent of global reserves. This would shift the balance of power in global oil markets away from OPEC.

That might then allow the President to drive down oil prices towards his targeted US$50 per barrel and ease affordability concerns at home. At the same time, renewed access to Venezuela’s heavy crude would also be helpful for US Gulf Coast oil refineries which are set up to handle that type of oil.

It's fair to say that many critics are deeply unconvinced by all this. They point to the fact that – as noted above – the global oil market is currently in surplus, with estimated supply running comfortably ahead of demand. In turn, this means oil prices are not only relatively low right now, but they are currently well below the kind of level that would make new investment in Venezuela look commercially attractive. Venezuelan oil is mostly extra-heavy crude from the Orinoco Belt (in the past, Trump himself has described Venezuelan oil as ‘the dirtiest, worst oil probably anywhere in the world’). Breakeven costs here are more than US$80 per barrel, which is well above both current prices and breakeven prices for alternatives such as Canadian tar sands. Complicating matters still further is the catastrophic state of Venezuelan oil facilities, with consensus estimates suggesting that a broad recovery in capacity would require between US$10 billion to US$20 billion of investment a year over the space of about a decade. And that capex would need to be delivered in an extremely challenging investment environment characterised by ‘gangs, goons and guerillas’. Then there is the discomfort that asuccessful effort to lower oil prices would imply for the domestic US oil industry.

Despite all this perfectly reasonable scepticism, however, the oil story still meshes with broader geo-economic and geopolitical narratives suggesting the return of the energy weapon and a new era of resource imperialism.

Further, note that there is significant overlap between these two interpretations. If Washington can secure a degree of control over Venezuelan oil, it can thereby disrupt Beijing’s access to cheap, sanctioned oil. China has been Venezuela’s biggest buyer since the start of the current decade, receiving an estimated 395,000 barrels per day last year (about four per cent of China’s seaborne crude imports) on one count. China also buys sanctioned oil from Russia and Iran, and in both cases disruption risk has risen in recent months. Maduro’s removal is also seen as a setback for Beijing’ s influence in the Western hemisphere more broadly.

To date, the direct implications of these developments for Australia have been limited. However, Canberra will not welcome a new world order predicated on resource imperialism and great power spheres of influence. Australia has been rightly able to pride itself as being an efficient and reliable resource exporter and has enjoyed significant economic benefits from that status. In the new order, operatingconditions seem set to become more challenging.

One recent, albeit quite modest, sign of the potential discomforts involved can be seen in the iron ore relationship with China. Last year, tough negotiations between the China Mineral Resources Group (CMRG), China’s state-run iron ore buyer, and BHP over the price of iron ore reportedly saw Beijing halt purchases of the company’s product and issue directives to import terminals in order to dent the pricing power of mining companies, prompting Prime Minister Albanese to express his concern. According to recent reporting, CMRG is expected to continue flexing its muscles into this year.

Powell under pressure: Another crack in the edifice of Central Bank independence?

Turning from geopolitical developments to central banking, last Friday, the US Department of Justice delivered grand jury subpoenas to the Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell regarding testimony he gave to the US Senate Banking Committee regarding the costly renovation work on the Fed’s HQ. On Sunday, Powell responded with a statement arguing that the move was part of the current administration’s efforts to exert greater control over US monetary policy. According to Powell:

‘This new threat is not about my testimony last June or about the renovation of the Federal Reserve buildings…Those are pretexts. The threat of criminal charges is a consequence of the Federal Reserve setting interest rates based on our best assessment of what will serve the public, rather than following the preferences of the President. This is about whether the Fed will be able to continue to set interest rates based on evidence and economic conditions—or whether instead monetary policy will be directed by political pressure or intimidation.’

In a press conference at the end of last year, President Trump did tell reporters that ‘We’re thinking about bringing a suit against Powell for incompetence,’ and remarked that the cost of renovation was ‘the highest price of construction per square foot in the history of the world.’ But Trump has now denied any direct role in the subpoenas, telling journalists ‘I don’t know anything about it, but he’s certainly not very good at the Fed, and he’s not very good at building buildings.’

Of course, one irony here is that it was President Trump that nominated Powell to be Fed Chair in back in November 2017, with his nomination citing Powell’s ‘steady leadership, sound judgement and policy expertise.’ Yet by 2018 tensions had already emerged, when the Fed’s decision to start tightening monetary policy drew Trump’s ire, with the President describing Fed policy as variously ‘crazy’, ‘loco’, and ‘ridiculous’ and calling its rate increases ‘a big mistake.’ By August 2019, with a US-China trade war underway, the President was asking ‘who is our bigger enemy, Jay Powell or Chairman Xi?’

During his second term, President Trump has once again been deeply unhappy with the Fed’s approach to monetary policy, last year attacking Powell for what Trump sees as the central bank’s failure to cut interest rates quickly enough. As well as bashing Powell repeatedly on social media, in April 2025 President Trump discussed the possibility of firing the Fed chief, declaring to reporters that ‘If I want him out, he’ll be out of there real fast’ although Trump subsequently said he had never had any plans to dismiss Powell.

As part of the White House campaign to exert greater control over US monetary policy, Powell has not been the only target. Last year, the Trump administration sought to remove Fed governor Lisa Cook from her position, citing allegations that she submitted fraudulent information on mortgage applications. In that context, the US Supreme Court is set to hear arguments later this month over the scopeof presidential power when it comes to dismissing Fed officials.

Yet through all this, Powell has largely avoided a direct confrontation with the Trump administration. Friday’s subpoenas changed his mind.

Powell’s term as Fed Chair ends in May this year anyway and the White House is already considering potential successors including the ‘two Kevins’ - White House economic adviser Kevin Hassett and former Fed governor Kevin Warsh. With President Trump having declared via a post on Truth Social that ‘anybody that disagrees with me will never be the Fed Chairman,’ an obvious question is why the White House doesn’t just wait for Powell’s departure?

One theory is that the pressure on Powell reflects a broader play for control of the Fed’s seven-member board of governors. Typically, most Fed chairs step down at the end of their term, but if he were so minded, Powell would in theory be able to stay on as a governor until 2028, effectively blocking the administration from adding another Trump-friendly appointment. Currently, two of the seven Fed governors were appointed by the first Trump administration while a third – Stephen Miran, previously the chair of Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers - was appointed in September last year.

Another theory is that the White House is sending a broader signal to the Fed at large about itsdesire for monetary policy acquiescence.

Last year we argued that fiscal dominance – the effective subordination of monetary policy to fiscal policy – was a strong candidate for the next big economic ‘regime shift’ to reshape the world economy. The argument was partly economic, highlighting the consequences of large fiscal deficits, high public debt to GDP ratios, a deterioration in the relationship between interest and growth rates, and ongoing shifts in the nature of the investor base for government debt. It was also partly political, noting that the rise of populism was an uncomfortable fit with the technocratic idea of independent central banks. These latest developments are in line with that prediction.

The proposition that the stakes for central bank independence are high is supported by the response of central bankers past and present to recent events.

The three former extant US Fed Chairs – Janet Yellen, Ben Bernanke and Alan Greenspan – have joined other prominent US economic figures in signing a statement declaring that ‘The Federal Reserve’s independence and the public’s perception of that independence are critical for economic performance…The reported criminal inquiry into Federal Reserve Chair Jay Powell is an unprecedented attempt to use prosecutorial attacks to undermine that independence.’

Likewise, a dozen central bank governors from leading international central banks including Australia’s own RBA as well as the ECB, the Bank of England, and the Bank of Canada have issued a statement of their own announcing that ‘We stand in full solidarity with the Federal Reserve System and its Chair Jerome H. Powell. The independence of central banks is a cornerstone of price, financial and economic stability in the interest of the citizens that we serve. It is therefore critical topreserve that independence….’

And yet.

If recent developments do in fact herald a major financial regime change, market reaction to date has been remarkably modest. Yes, gold and silver both jumped to record highs on Monday this week following Powell’s Sunday Statement. And the US dollar did weaken a little. All of which was enough to allow some observers to detect a modest version of the so-called ‘debasement trade’ (which involves diversifying out of the US dollar into gold and other alternatives). But set against that was the mild reaction of Treasury markets, which would in theory be worried about higher inflation risk, which seemed to suggest that markets just didn’t care very much. For its part, the share market – which would benefit from lower interestrates, at least in the short term – appeared to be largely unaffected.

So, does that market reaction signal a collective judgement that Fed independence will survive this latest scrape intact? Or to the contrary, that markets have already priced in the fiscal dominance theory? Perhaps even more radically, does it tell us that markets are just not that bothered about central bank independence after all? Then again, this could just be the latest example of market complacency in the face of big structural shifts in the global environment.

Australia’s inflation rate eased – slightly– in November 2025

Finally, returning to Australia and the domestic economy, readers will remember that towards the end of last year, the debut of Australia’s new monthly CPI delivered an uncomfortably high inflation reading. The annual rate of headline inflation for October 2025 had printed well above target at 3.8 per cent while underlying inflation as measured by the trimmed mean hit 3.3 per cent. Those results, along with a surprisingly strong set of numbers for the September quarter 2025, contributed to the hawkish message delivered by the RBA after the December 2025 meeting of the Monetary Policy Board (MPB). As a result, markets began to treat the February 2026 MPB meeting as ‘live.’

Last week, the November 2025 inflation numbers reported a modest drop in the headline and underlying annual rates, but not by enough to materially change the policy debate at Martin Place (on which, see below) as both measures remained above the top of the RBA’s target band. According to the ABS, the headline inflation rate slowed from 3.8 per cent to 3.4 per cent. On a monthly basis, the CPI was unchanged in original terms (but up 0.2 per cent on a seasonally adjusted basis).

The decline in underlying inflation (as measured by the trimmed mean) was smaller, with the rate easing from 3.3 per cent to 3.2 per cent. In month-on-month terms, thetrimmed mean rose 0.3 per cent.

The Bureau said that the largest contributor to annual inflation in November was the Housing group, which was up 5.2 per cent, down from 5.9 per cent in October. Within that group, the main drivers were Electricity (up 19.7 per cent vs 37.1 per cent in the previous month*), Rents (up four per cent) and New Dwellings (up 2.8 percent).

*The ABS notes that excluding the impact of Commonwealth and State Government electricity rebates over the past year, electricity prices rose 4.6 per cent over the year to November compared to five per cent rise in October.

Most analytical measures of inflation (see table below) likewise reported a slight deceleration relative to the October readings.

What has the RBA been saying about monetary policy?

What does that result mean for RBA policy? To provide a bit of context to that question, it is first worth noting that we have received a couple of additional pieces ofcommunication from Australia’s central bank since our last weekly update.

First up, back on 23 December 2025, the RBA published the Minutes of the December 2025 Monetary Policy Board (MPB) meeting. Recall, that on 5 December last year Governor Michele Bullock had told the post-meeting press conference that:

‘I don’t think there are interest rate cuts in the horizon for the foreseeable future. The question is, is it just an extended hold from here or is there possibility of a rate rise? I couldn’t put a probability on those, but I think they’re the two things that the Board will be looking closely at coming into the new year.’

The detail of the Minutes reinforces the hawkish shift that was apparent in the immediate post-meeting rhetoric, albeit tempered by a degree of caution as to whether the appropriate response will require a rate increase or an extended period of an unchanged cash rate policy.

Thus the Minutes explain that while ‘the September quarter CPI release had been well above the forecast published in the August Statement…[and]…the detail within the October monthly CPI data pointed to the possibility that inflation in the December quarter could also be higher than had been expected in the November forecast…’, there were also ‘several reasons to be cautious about how much signal to draw from these data.’

Likewise, MPB members were also uncertain as to whether financial conditions were restrictive or not, with the Minutes reporting that while some ‘members judged that, on balance, financial conditions were perhaps no longer restrictive’ others ‘assessed that, on balance, financial conditions were a little restrictive.’Quite…balanced, then.

Overall, the Minutes sum up:

‘Members noted that the economy appeared to be operating with a degree of excess demand and it was not clear whether financial conditions were sufficiently restrictive to bring aggregate demand and supply back to balance. Members discussed the circumstances in which, should these trends persist, an increase in the cash rate might need to be considered at some point in the coming year.

However, members judged that it was too early to determine whether inflation would be more persistent than they had assumed in November, given the uncertainties about the reliability of the signal from the new data series at present.’

And go on to say:

‘Overall, while recent data suggested the risks to inflation had tilted to the upside, members felt it would take a little longer to assess the persistence of inflationary pressures. As a result…it was appropriate to leave the cash rate target unchanged at this meeting and assess at future meetings how their judgements about the key considerations had evolved.’

Importantly, this discussion predated last week’s inflation numbers.

Second, and more recently, on 8 January this year, RBA Deputy Governor Andrew Hauser told an interviewer from the ABC that rate cuts remain off the central bank’s near-term agenda:

‘It’s true…that in the December meeting…the Governor said that in light of the most recent inflation data…that the likelihood, at least in the near term, of further rate cuts was probably very low. That’s still true, I think, if I’m honest with you.’

And with direct reference to the November 2025 inflation results, Hauser said:

‘It ticked down. That was helpful. But it was largely as we had expected, and we…will be waiting for the quarterly inflation in about two- or three-weeks’ time before we take a view on where we think inflation is today. But inflation above three per cent, let’s be clear, is too high. We’re charged to keep inflation between two to three per cent and it’s currently above that.’

It follows that the November inflation numbers will do little to alter the likelihood that the MPB members will once again be debating whether inflation requires a pre-emptive rate hike, or if Martin Place can continue December’s policy of watching and waiting.

At the time of writing, financial markets were pricing in a roughly one-in-three chance of a rate rise next month. By then, however, the MPB will have new data from the December monthly labour force report (due on 22 January) and the December quarterly and monthly inflation readings (due 28 January) to hand. Those numbers are likely to play an important role in informing the MPB’s decision.

Other Australian data points to note

ANZ-Indeed Australian Job Ads fell 0.5 per cent over the month in December 2025 to be 7.4 per cent lower over the year. The December monthly drop followed a downwardly revised 1.5 per cent decline in November last year and marked thesmallest monthly fall in six months.

In another read on the Australian labour market, the ABS reported that total job vacancies in November 2025 were down 0.2 per cent from their level in August last year (seasonally adjusted), and 5.2 per cent lower compared to November 2024. Private sector vacancies drove that annual decline, dropping by 6.8 per cent over the year, while public sector vacancies were up 8.9 per cent over the same period. Vacancies are now down 31 per cent from their May 2022 peak but are still 42 per cent higher than they were in pre-pandemic November 2019.

The ABS Monthly Spending Indicator delivered another strong result in November 2025. According to the Bureau, household spending was up one per cent month-on-month (current prices, seasonally adjusted) and 6.3 per cent higher over the year. That followed a monthly increase of 1.4 per cent in October, with the ABS highlighting the impact of major events on spending on services (up 1.2 per cent over the month) and of Black Friday sales on goods expenditure (up 0.9 per cent in monthly terms).

Earlier this month, Cotality said that its National Home Value Index rose 0.7 per cent in December 2025 to leave the index up 8.6 per cent relative to December 2024. The Combined Capitals Index was up 0.5 per cent month-on-month and 8.2 per cent year-on-year. Cotality said that the monthly gain in the National Index was the smallest in five months and highlighted small monthly declines (each of 0.1 per cent) in Sydney and Melbourne. According to the data provider, the relatively soft end to the year reflected the combined impact of changed assumptions on the trajectory of interest rates (now likely to be higher for longer) plus cost-of-living pressures and worsening affordability.

Further reading and listening

- Treasury’s PopulationStatement 2025.

- And Treasury’s 2025-26 Tax Expenditures and Insights Statement.

- On the cost of Victoria’s fire damage.

- On Australia-China trade.

- The Lowy Interpreter considers Australia’s emerging Greenland dilemma.

- Eurasia group’s top risks 2026.

- A WSJ long read examines the obscure bank collapse that sent Iran into a tailspin.

- Related, a look at the deep roots of Iran’s economic crisis.

- The Economist magazine reckons that an American oil empire is a deeply flawed idea.

- An OECD Policy Brief on the role of subsidies in the solar panel industry.

- A new edition of the BIS Bulletin examines the financing of the AI boom.

- The IMF on new job creation in the AI Age.

- While US CFOs struggle to see any impact from AI on labour productivity, decision-making speed, customer satisfaction, or time spent on high value-added tasks.

- So, will the economy survive the AI revolution?

- From the FT, why the world has started stockpiling food again.

- Also from the FT, (US) economists are facing their own recession due to waning interest, declining student demand, and a cratering job market.

- Recent episodes of Bloomberg’s Odd Lots podcast consider the fight over Fed independence, the Donroe Doctrine, and Venezuela and the oil market.

- For related perspectives, the FT’s Unhedged podcast on the showdown at the Federal Reserve and Imperialism and the markets.

- The UnHerd podcast explains Why Trump will get Greenland.

- And the LRB podcast asks John Lanchester, will the AI bubble burst?

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content