It has been a quiet week on the domestic data front. The main economic news came in the form of the minutes to this month’s Monetary Policy Board (MPB) meeting, which set out why a majority of the Board had resolved to leave policy on hold, despite a cross-MPB consensus that more rate cuts were inbound.

Based on the Minutes, that majority view was that a ‘cautious and gradual’ approach to easing was merited and that this approach was more consistent with a temporary pause in the easing cycle. That caution reflects ongoing central bank uncertainty regarding both the level of the ‘neutral’ cash rate and the true extent of labour market tightness. As well as a desire to see the more reliable June quarterly CPI reading before cutting rates again, (rather than relying on the volatile monthly CPI Indicator readings). Taking the MPB Minutes at face value, the implications are that the RBA will continue to ease policy, but that it will do so gradually and that the remaining amount of easing will be ‘modest’. All that, of course, is conditional on the economy continuing to track in line with the central bank’s forecasts.

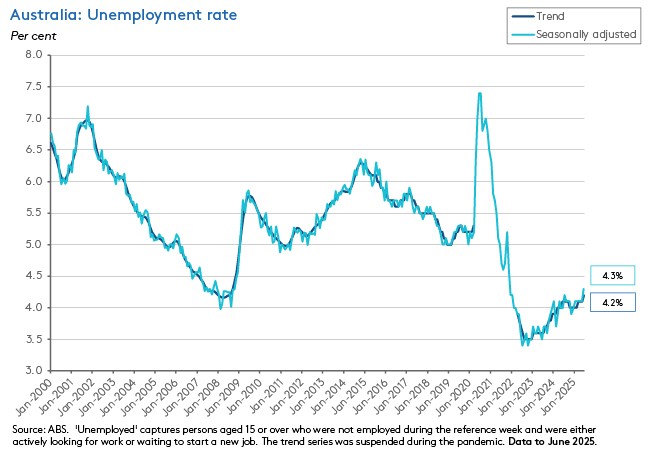

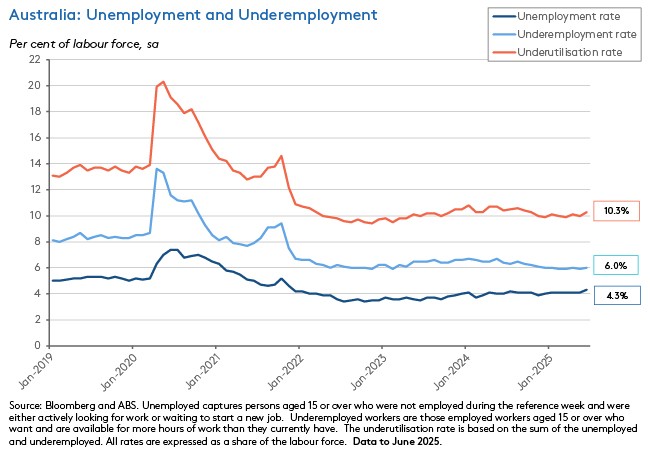

Worth mentioning in this context are last week’s labour market results, which printed weaker than the median forecast as the unemployment rate rose to 4.3 per cent and its highest level since November 2021. Employment growth was also weak. These signs of labour market softening are in line with the central bank’s forecasts and as such should be consistent with the RBA delivering another rate cut at next month’s meeting, provided that the June quarter CPI (due on 30 July) does not deliver an unpleasant surprise in the meantime. On that front, the Governor warned in a speech this week that the RBA judged that the pace of disinflation as measured by the trimmed mean could turn out to be a little slower than the RBA had projected back in May. So, one to watch.

Meanwhile, central banks – notably the US Federal Reserve – have also been prominent in the international financial news in recent weeks. Commentators and markets have focused on President Trump’s long-running antagonism towards Fed Chair Powell, with Trump once again calling on Powell to reduce interest rates while musing openly about firing him. Powell’s term as Fed chair ends in May next year (although his term as governor runs until January 2028) and markets are already speculating that his replacement is likely to be a more biddable Trump loyalist. The current bout of pressure on US central bank independence is perhaps the most prominent example of what central bank watchers worry is a more general risk of ‘fiscal dominance’. Below, we examine the thesis that fiscal dominance could be the next episode of a global regime shift to follow the dramatic changes to the international trading system already underway.

We also dig into last week’s labour market numbers, including a look at trends in market vs non-market sector hours worked, summarise the rest of this week’s data releases and deliver our regular linkage roundup which includes the announcement of a new complete Monthly CPI. As usual, if you’d like to see the charts that accompany the analysis, please click through to read the web site version.

Will ‘fiscal dominance’ be the next big regime shift?

Earlier this year, we argued that the Trump administration’s tariff policies marked a significant global regime shift in the domain of international trade policy. Subsequent events including but not limited to the ‘Liberation Day’ tariff announcements, have confirmed that judgement.

Now, a new candidate for regime shift has emerged in the form of ‘fiscal dominance.’ Fiscal dominance arises when monetary policy becomes effectively subordinate to fiscal policy, such that budgetary constraints leave the central bank finds unable to raise interest rates and tighten policy. Those constraints can take two broad forms. First, the central bank may be subject to political pressure to keep interest rates low to reduce debt servicing costs and increase fiscal space. Second, budget constraints – in the form of extremely high debt and debt service burdens – may eventually become so binding that any attempt to increase interest rates would push debt service to levels that would trigger fiscal and economic crises. Under some conditions, this could even involve a resort to direct monetary financing. The canonical economic paper here is Neil Wallace and Thomas Sargent’s 1981 Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic. It argues that in circumstances where fiscal policy dominates monetary policy, such that the fiscal authority independently sets its budgets and the monetary authority, then treats the subsequent profile of debt and deficits as constraints in terms of the amount of financing to be raised by bond issuance and seigniorage (the profits from issuing currency), the monetary authority could find itself unable to control either the growth rate of the monetary base or inflation. This will tend to be the case when the interest rate on government bonds (r) is greater than the growth rate of the economy (g).

The risk of fiscal dominance is on the rise due to a combination of factors.

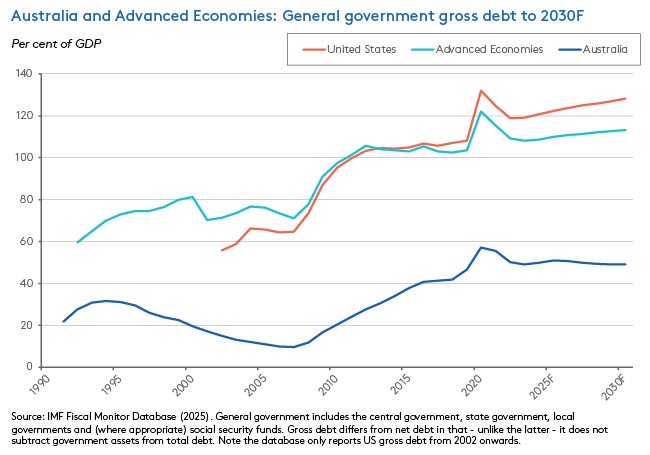

First, and underpinning the whole story, is the emergence across advanced economies of large fiscal deficits and high debt-to-GDP ratios. These are products of the global financial crisis (GFC) and the Great Recession that followed, and more recently of the COVID-19 pandemic and the extensive fiscal policy response. Exacerbating fiscal risk is the prospect of rising budgetary pressures over the medium term. Rich world governments face a growing fiscal burden due to population ageing, looming investment costs associated with the energy transition and escalating pressures to spend more on defence in an insecure world.

Further worsening the situation is the risk of a deteriorating relationship between the interest rate paid on public debt (r) and the growth rate of the economy (g), given by r-g. When growth rates are persistently higher than the interest rate paid on public debt (that is, when r – g is negative) this is good news for debt dynamics. Worryingly, however, there are significant uncertainties over the future trajectory of both variables.

In the case of g, medium-term economic growth prospects face multiple headwinds in the form of low rates of actual and potential growth weighed down by lacklustre productivity, rising policy uncertainty, elevated geopolitical risks and increased levels of protectionism. Regarding r, interest rates – and therefore government borrowing costs – are under upward pressure not just from the present high debt burden but also from the risk of higher inflation in an environment that looks likely to be characterised by more adverse supply shocks. Higher risk premia could also push bond yields up yet further if inflation risks prove to be more persistent or if government fiscal credibility erodes.

Another complication is the changing nature of the investor base for government debt. The latest BIS Annual Economic Review highlights how the current reduction in central bank holdings of government securities (due to the unwinding of bond purchases associated with previous bouts of quantitative easing) is changing the balance of supply and demand in government debt markets. The BIS cites evidence that these shifts have already generated some widening in term premia as private investors must fill the gap left by official purchases. At the same time, investor appetite for government bonds more generally has shown signs of weakening. The BIS reckons this diminution in appetite could reflect a rising correlation between stocks and bonds (implying a reduction in the traditional hedging properties of government securities for investment portfolios) as well as a response to increased inflation expectations and inflation uncertainty. These developments have already led to lower convenience yields on US Treasuries (that is, the premium investors place on holding government bonds for their safety and liquidity seems to have fallen).

The Review also emphasises that high public debt burdens create financial vulnerabilities, for example, by making the financial system vulnerable to falling asset values triggered by rate increases. A large repricing of government debt can lead to substantial losses for banks and any other financial institutions with large sovereign debt exposures. The BIS notes that these vulnerabilities can play out not just in response to an explicit tightening of monetary policy but also in response to perceived increases in fiscal risk, citing the UK gilt market disruption in September 2022 as an example.

Another crucial element in this story is the rise of populism, which on one measure is at or close to all-time highs in terms of the share of countries which now have populist governments. History suggests that populism is typically associated with macroeconomic instability across at least three areas. First, populist governments tend to embrace economic nationalism and protectionist trade policies. Second, they are often associated with higher public debt and higher inflation rates. Third, they are frequently tempted to tamper with existing institutions and here central bank independence offers a potentially attractive target.

Finally, and related, the ongoing confrontation between the Trump Presidency and the US Federal Reserve has propelled the issue of central bank independence back into the headlines. Trump’s frustration with the Powell-led Fed is longstanding, but in recent weeks his public attacks have focused on the need for the Fed to cut interest rates to lower the cost of US government debt service.

Fears of fiscal dominance last spiked in the aftermath of the GFC, as the consequent massive increase in central bank balance sheets, swollen government budget deficits and sharp increase in public debt burdens combined to prompt concerns that the boundary between monetary policy and government debt management was becoming increasingly blurred. Then, central bank independence emerged relatively unscathed. Whether it will do so again remains to be seen.

MPB Minutes show board favours a ‘cautious and gradual’ approach to monetary easing

This week brought the publication of the Minutes of the Monetary Policy Board (MPB) meeting held on 7-8 July 2025 at which the RBA surprised financial markets and most RBA watchers (including this one) by leaving the cash rate target unchanged at 3.85 per cent. As the Minutes report:

‘Members noted that a 25 basis point reduction in the cash rate at the current meeting was almost fully priced in by market participants and was also expected by most market economists…Members acknowledged that there had been previous occasions when market participants had been very confident about the outcome of a monetary policy decision, but the (Reserve Bank) Board had decided on an alternative course.’

As we know, the Board split over the decision, with six members voting in favour of leaving policy unchanged and three opposed. The Minutes set out the broad contours of the debate, starting by emphasising the common ground across the MPB:

‘All members agreed that, based on the information currently available, the outlook was for underlying inflation to decline further in year-ended terms, warranting some additional reduction in interest rates over time. The focus at this meeting was on the appropriate timing and extent of further easing, against the backdrop of heightened uncertainty.’

So, there was no disagreement on the proposition that the cash rate would need to fall from its current rate. Instead, the debate was over the timing of the next rate cut. According to the Minutes, the case for sticking with the status quo this month reflected several considerations:

- Some recent economic indicators had either been in line with or slightly stronger than RBA staff projections. For example, the RBA judged that a few monthly indicators of inflation were marginally higher than would be consistent with the May 2025 Statement on Monetary Policy (SMP) forecasts for June quarter inflation, which called for a 2.1 per cent annual headline rate and 2.6 per cent underlying inflation.

- At the same time, ‘the sharp declines in the [May] monthly indicators for headline and trimmed-mean inflation were likely to have overstated the easing in underlying inflation momentum’.

- In addition, an apparent reduction in the likelihood that the most severe negative scenarios for the world economy around trade policy and tariffs will play out meant that expectations could now apply less weight to downside scenarios and more to the central case SMP forecast.

- That same SMP forecast was conditioned on ‘a relatively modest and gradual path of further easing of monetary policy’.

- There was some risk that if low productivity growth persisted, then recent supposedly ‘subdued’ GDP outcomes were in fact broadly consistent with the effective supply capacity of the economy.

- Members were unsure as to just how far interest rates needed to fall before monetary policy ceased being restrictive and returned to a neutral setting. Given that uncertainty, ‘it might be prudent to lower interest rates cautiously as the required degree of policy restrictiveness declines’.

In contrast, the minority view was that:

’…there was already sufficient evidence to be confident that inflation was on track to be sustainably back at the midpoint of the target range, if not lower. This implied less need to wait before easing policy further, which was a relevant consideration given the lags in the effect of monetary policy on economic activity and inflation.’

This side of the argument also stressed the downside risks associated with ongoing uncertainty around the global economic outlook, as well as concerns about the strength of domestic activity and the labour market. (These applied where there was a risk that market sector employment might not pick up enough to offset an expected slowdown in the growth of non-market sector employment).

Again, we already know the outcome of this debate:

‘…a majority of members judged that the case to hold the cash rate target unchanged at this meeting was the stronger one. They believed that lowering the cash rate a third time within the space of four meetings would be unlikely to be consistent with the strategy of easing monetary policy in a cautious and gradual manner to achieve the Board’s inflation and full employment objectives’.

There are three other points worth highlighting from this week’s release.

First, and as already touched on, the MPB remains uncertain about the level of the neutral cash rate. According to the Minutes, the board spent some time discussing how best to assess ‘neutral’. The forecasts in the May SMP suggested that underlying inflation would stay around the midpoint of the target range and the labour market would remain close to full employment, based on an assumption that the cash rate would decline gradually to a little over three per cent by the middle of next year. It follows that the RBA judges the current setting of monetary policy is only modestly restrictive – that is, quite close to neutral. Likewise, the Minutes report that the average of a range of alternative model-based estimates of the neutral rate point to a similar conclusion, although it cautions that such estimates are ‘subject to considerable dispersion and uncertainty and the average is sensitive to the choice of models included in the range’.

Second, the Minutes note that at the start of this year employment growth in the non-market sector had started to ease from its previous rapid pace, while employment growth in the market sector had picked up a little in year-ended terms. In this context, the MPB judged that ‘a key consideration for the economic outlook was the extent to which any further slowing in growth in non-market sector employment and activity would be offset by stronger growth in the market sector.’ (For more on the market vs non-market split, see the labour market analysis that follows below.)

Third, MPB members also discussed the degree of spare capacity in the labour market. At the time of the meeting, the unemployment rate had been stable for almost half a year and the assessment of RBA staff was that labour market conditions were tight, although this judgement came ‘with a considerable degree of uncertainty’. The Minutes say that relatively low unemployment and underemployment rates and a relatively high ratio of job vacancies to unemployed workers all supported this view, as did ongoing elevated growth in unit labour costs, albeit with that mostly due to weak productivity growth.

On the other hand, measures of job mobility had fallen and growth in the wage price index (WPI) had slowed.

Earlier this month, then, the majority of the MPB wanted to stick with a ‘cautious and gradual’ approach to returning the cash rate to a more neutral setting. A sense that the cash rate was already reasonably close to neutral and a judgement that the labour market remained tight reinforced that caution, although in both cases those assessments came with a relatively high degree of uncertainty attached. It follows that, should the economy continue to track in line with the RBA’s forecasts (an important caveat!) we should (1) continue to expect more rate cuts from here but (2) also expect them to be delivered relatively slowly and (3) anticipate a neutral or terminal rate likely to be around three per cent.

Last week’s labour force results suggest the labour market is softening

While the weekly note was taking a short break last week, the ABS reported that Australia’s unemployment rate rose to 4.3 per cent in June 2025 (seasonally adjusted), up from 4.1 per cent in May. That was a weaker result than the consensus market forecast for a 4.1 per cent rate. It also ended a sequence of five consecutive months of an unchanged unemployment rate and marked the highest rate recorded since November 2021. On a trend basis, the unemployment rate also edged higher, rising from 4.1 per cent in May to 4.2 per cent last month. By way of comparison, the forecasts in the RBA’s May Statement on Monetary Policy have unemployment averaging 4.2 per cent across the June quarter (in line with the actual outcome) before rising to 4.3 per cent in the December quarter of this year.

The underemployment rate also increased in June, rising to six per cent from 5.9 per cent in May. As a result, the combined underutilisation rate climbed to 10.3 per cent from ten per cent over the same period.

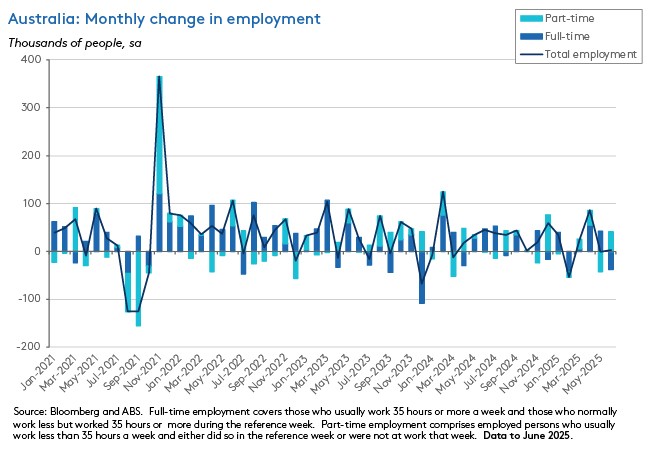

In another sign of emerging labour market softness, employment rose by a subdued 2,000 persons last month. That was weaker than the consensus forecast, which had anticipated an increase of 20,000 people and followed a 1,100 fall in employment in May. Full-time employment fell by 38,200 in June while part-time employment rose by 40,200.

Monthly hours worked in all jobs fell by 19 million hours, a decline of 0.9 per cent from May.

The employment to population ratio was unchanged at 64.2 per cent last month, while the participation rate increased slightly, rising from 67 per cent in May to 67.1 per cent in June. That increase – the rise in people looking for work – explains the monthly rise in the unemployment rate, as the growth in employment failed to keep up with the increase in labour supply.

A look at hours worked in the market and non-market sectors

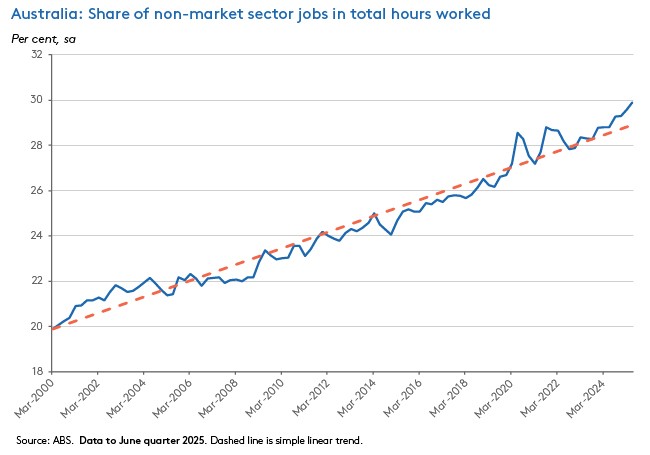

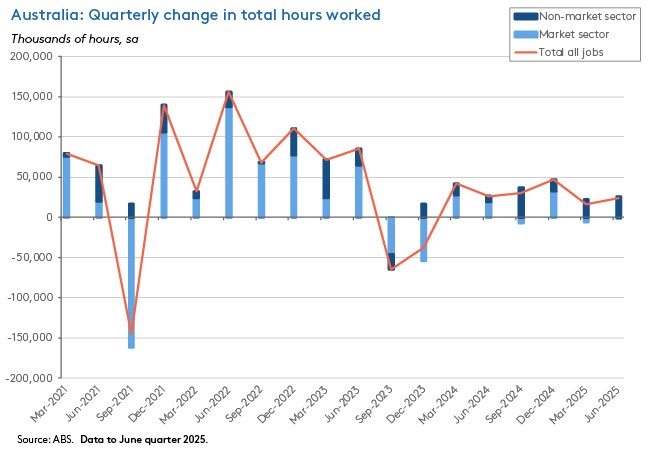

The June labour force release also included quarterly data on the split between hours worked in the market and non-market sectors (the latter comprises three industries: Public administration and safety; Education and training; and Health care and social assistance). Trends in non-market vs market sector employment have been a popular theme over the past year and were also referenced in the latest MPB Minutes discussed above, so a quick look at the numbers is worthwhile.

Two key points stand out.

First, the rise in the non-market sector share in total hours worked is a long-running trend, although there are signs that the pace of increase has increased in the aftermath of the pandemic (see chart below). At the start of the 2000s (March quarter 2000) non-market jobs accounted for 19.9 cent of total hours worked. By the end of the decade (December quarter 2009) that share had risen to 23 per cent. By the end of the next decade (December quarter 2019) it had risen again, climbing to 26.7 per cent. And as of the June quarter this year, the share stood at 29.9 per cent.

Second, a look at the recent quarterly change in hours worked by sector shows that the non-market sector has driven much of the rise in hours worked. For example, over the year from the June quarter 2024, the non-market sector accounted for about 84 per cent of the increase in total hours worked in all jobs.

What else happened on the Australian data front this week?

- The S&P Global Flash Australia Composite PMI Output Index rose from 51.6 in June 2025 to 53.6 in July 2025, indicating that growth in business activity in Australia gathered pace at the start of the September quarter of this year. The index has now been above a neutral 50 reading for ten consecutive months with July’s reading the strongest since April 2022. According to S&P, the acceleration in activity reflected the first rise in manufacturing production in three months, the fastest expansion in services activity for 16 months, and the strongest rise in overall new orders in 39 months (although manufacturing export orders remained in contraction). Less positively, business confidence fell to an eight-month low this month, although it remained in positive territory overall. The July PMI survey results also pointed to increased price pressures, with average input prices climbing at their fastest pace in three months due to higher service sector cost inflation more than offsetting an easing in manufacturing input price inflation.

- The ANZ-Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence Index was little changed last week, falling 0.2 points to 86.3 points in the week ending 20 July 2025. Across the various subindices, there were increases for short-term and medium-term economic confidence that were largely offset by falls for current and future financial conditions and for the ‘time to buy a major item’ subindex. Weekly inflation expectations fell 0.2 percentage points to 4.7 per cent.

- The ABS said that payroll jobs increased 0.7 per cent in the month from 15 February 2025 to the week ending 15 March 2025. Job numbers were up 0.2 per cent over the year. The Bureau also announced that this was the final release in this series. The Payroll Jobs indexes will now be replaced by a new monthly Employee Jobs measure, that will appear in the Monthly Employee Earnings Indicator from February 2026.

Other things to note...

- The ABS has announced that its work to transition from the quarterly Consumer Price Index (CPI) to a complete monthly measure was on track, with Bureau to commence a Monthly CPI publication on 26 November 2025. The new Monthly CPI data series and the new monthly analytical series will include back data to April 2024. They will replace the current Monthly CPI Indicator series, which will cease publication. More detail on the complete monthly measure.

- RBA Governor Michele Bullock gave a speech on The RBA’s dual mandate – Inflation and employment. As part of her remarks, and in line with message from Minutes discussed above, she noted that ‘The Board continues to judge that a measured and gradual approach to monetary policy easing is appropriate.’ According to the Governor, the RBA still expects the annual rate of trimmed mean inflation in the June quarter to slow from its 2.9 per cent rate in the March quarter, but perhaps not quite to the 2.6 per cent rate it forecast back in May. She also reminded her audience that the June quarter outcome for the unemployment rate (at 4.2 per cent) was in line with the central bank’s May forecasts, and that this meant ‘the labour market moved a little further toward balance’. Elsewhere in her speech, the Governor addressed the RBA’s success in bringing inflation down without a significant cost in terms of joblessness, which she attributed to the temporary nature of supply-driven price increases, stable inflation expectations, and greater labour market adjustment through lower vacancies and reduced hours work relative to less employment.

- Also from the RBA, the July 2025 Bulletin includes articles on a (closer to) real time labour quality index, on International students and the Australian economy, and how changes in global shipping costs affect Australian inflation. Notably, the first of these finds ‘little to no evidence that the entry of workers with less skills and human capital can explain weak productivity growth over recent years. In fact, human capital grew over the period, contributing to productivity growth, and this growth was if anything faster than what was observed over the years leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic. This suggests that productivity is unlikely to pick up as recent dynamics unwind – for example, through some of these workers gaining new skills or leaving the labour market. More generally, it suggests that other factors – including those evident before the pandemic – are contributing to the recent weak productivity outcomes.’ The piece on students reckons that ‘the rapid growth in international student numbers post-pandemic likely contributed to high inflation over this period, but was not a major driver’. Finally, the article on shipping costs reckons that ‘shocks to global shipping costs were large enough to have contributed materially to trimmed mean inflation during the pandemic’ although these is ‘substantial uncertainty’ around the estimates. There is also an updated Explainer on productivity.

- Leviathan Rampant: A new CIS report on the rising trend of government spending in Australia. According to the CIS, while Commonwealth real per capita expenditure has grown at an average annual rate of 1.8 per cent since 2012-13, annual real GDP growth averaged just 0.8 per cent over the same period as annual productivity growth averaged 0.5 per cent. The report highlights a dozen social spending, care economy and defence programs, along with public debt interest, that have averaged annual growth of almost 10 per cent over this period, lifting their share of the budget from around 35 per cent to almost 50 per cent in 12 years, with the NDIS dominating the story.

- The e61 Institute says there are better ways to cut student debt than current government policy.

- Michelle Grattan asks, what might the Treasurer get out of August’s economic reform roundtable? According to Grattan, any progress on rebalancing the tax system away from income to consumption is unlikely, with the government more likely to favour tax changes affecting wealth and the resources sector.

- The Economist magazine examines disaster-proof capitalism, writing that the global economy has been largely unmoved by our chaotic contemporary geopolitics, with world real GDP growth chugging along at a fairly consistent three per cent per annum. The magazine puts this shock-absorbing success down to the emergence of a new form of capitalism which it terms ‘the Teflon economy’. This combines firms that are better than ever at dealing with shocks, the shift to a more stable services-based economy, the rise of the United States as an alternative energy producer to Russia and the Middle East, and extreme fiscal activism on the part of governments – the average rich-country government now runs a fiscal deficit of more than four per cent of GDP plus holds vast contingent liabilities. Less cheerily, the piece notes that the disconnect between market values and geopolitical risk has echoes of…1940.

- Related, the WSJ says the global economy is powering through an historic increase in tariffs. Potential explanations for global economic resilience advanced here include pandemic-era lessons learned, including strengthened – and more localised – supply chains; lavish government spending, particularly in the United States and Germany; and a lower-than-expected hit from higher uncertainty. It is also possible that precautionary inventory buildups boosted activity.

- Why Trump’s trade threats aren’t working to secure durable, significant gains for the United States. This piece argues that the inability of the Trump administration to deliver credible commitments is part of the problem, as is the administration’s general unpopularity with non-Americans.

- Has the US Treasury market started to crack?

- Analysing some of the costs and benefits of a shorter working week.

- The BIS Bulletin series considers the policy implications of growing links between the traditional financial system and stablecoins.

- A new IMF working paper examines the energy origins of the post-pandemic global inflation surge

- Also from the IMF, the latest country report on Brazil.

- An FT Big Read asks, will the current drive to deregulate financial services spur growth or crisis? Or put slightly differently, is this just the latest episode in the familiar boom-and-bust pattern of financial regulation?

- Also from the FT, the growing BRICs divide between carbon nations and electrostates.

- The OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2025-34 says that global agricultural and fish production is expected to increase by 14 per cent over the next decade. This will mainly reflect productivity improvements, particularly in middle-income countries. The report also reckons that rising productivity will lead to a fall in real agricultural commodity prices over the medium term. Meanwhile, as demand for both food and animal feed grows, and with production often located far from consumption areas, the OECD estimates that 22 per cent of all calories will cross international borders over the next ten years.

- How to make sense of the AI revolution.

- The Odd Lots podcast talks about the pressures on Fed independence.

- Conversations with Tyler speaks with medievalist Helen Castor.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content