Overview

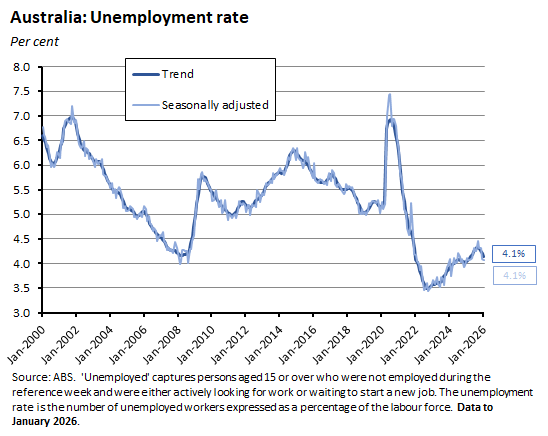

- Australia’s labour market continues to look tight. At 4.1 per cent, January’s unemployment rate remains a bit below the level that the RBA reckons is consistent with inflation at target.

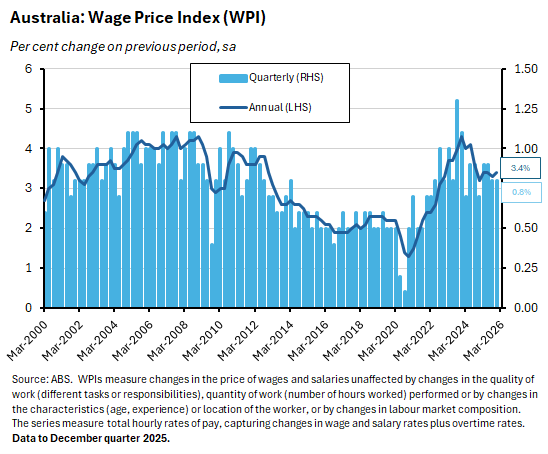

- Wage growth was little changed in the December quarter of last year, with the annual rate of increase in the Wage Price Index (WPI) running at 3.4 per cent. While our lacklustre labour productivity growth suggests that this pace sits uncomfortably with the inflation target, it was still not enough to stop real wage growth going backwards on an annual basis.

- Both the labour force and WPI readings are in line with the RBA’s recent assessment of economic conditions.

- The Minutes of the February 2026 meeting of the Monetary Policy Board highlight the central bank’s shift to a more hawkish judgement of inflation risks. At the same time, however, they also depict a Board that remains uncertain about the future path for policy and firmly in data-dependent mode.

TThis week, we review new numbers for employment and unemployment for January 2026 and for wage growth in the December quarter 2025. We also analyse the Minutes from the February 2026 Monetary Policy Board meeting. We see little in either the labour market data or in the Minutes to change our view that at least onemore rate increase remains the most probable outcome going forward. There is also our regular roundup of further reading and listening, including the latest IMF assessment of the Australian economy.

Labour market conditions remain tight

Australia’s unemployment rate remained unchanged at 4.1 per cent (seasonally adjusted) in January 2026, beating the consensus forecast for a slight uptick to 4.2 per cent. After peaking at almost 680,000 in September last year, the number of unemployed persons has now fallen for four consecutive months to stand at less than 625,000.

Measured on a trend basis, the unemployment rate fell to 4.1 per cent last month, down from 4.2 per cent in December 2025. That marks the lowesttrend unemployment rate since April 2025.

Despite a slight increase in hours worked over the month, the seasonally adjusted underemployment rate moved in the opposite direction to the unemployment rate, increasing by 0.2 percentage points to 5.9 per cent. That was enough to nudge the overall underutilisation rate back up to 10 per cent after the latter had fallen briefly into single digit territory in December last year.

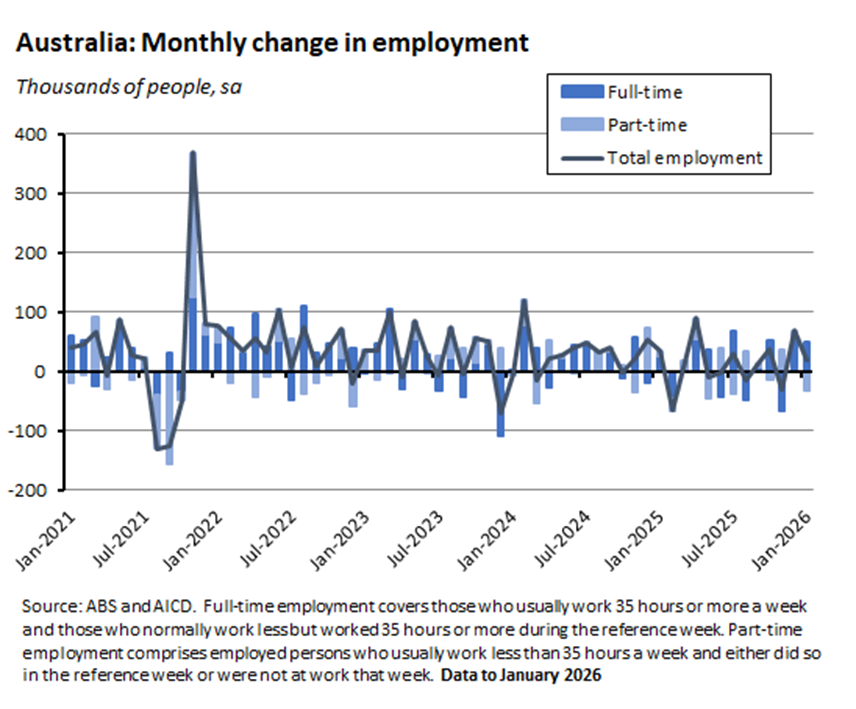

According to the ABS, the number of employed people rose by 17,800 over the month, driven by a 50,500 increase in full-time employment that was only partially offset by a 32,700 drop in part-time employment. In this case, the result was slightly weaker than the market had expected, with the consensus forecast having anticipated an employment gain of around 20,000. Month-by-month, the employment numbers continue to be volatile.

The participation rate was unchanged at 66.7 per cent in January, while the employment to population ratio edged down by 0.1 percentage point to 63.9 per cent.

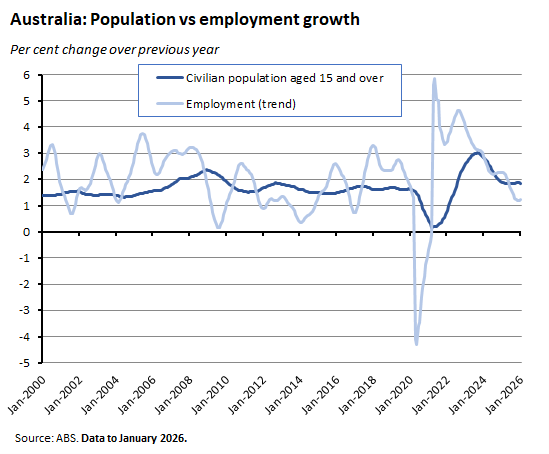

Most of this month’s labour force numbers were consistent with the story of a labour market where conditions remain on the tight side. Still, there were some contrary indications. Along with that tick up in the underemployment rate, recent results have also shown the trend pace of employment growth dipping below the pace of working-age population growth, suggesting the possibility of a future loosening in conditions as we move deeper into the year.

Wage growth little changed in December quarter 2025

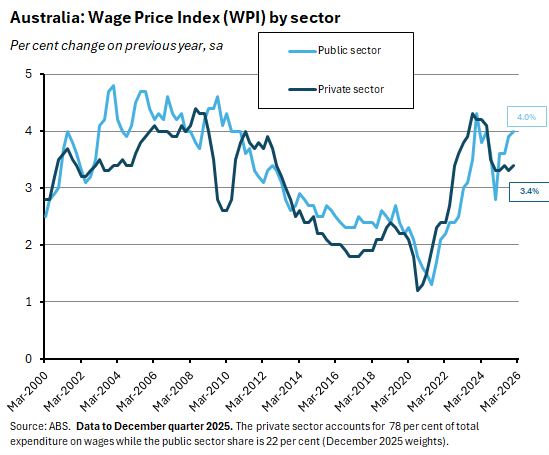

The ABS said the Wage Price Index (WPI) rose 0.8 per cent (seasonally adjusted) over the December quarter last year and was up 3.4 per cent year-on-year. Both quarterly and annual growth rates were in line with market consensus forecasts. The quarterly rate of wage growth was also unchanged from the September quarter 2025, while the annual rate ticked up from a revised 3.3 per cent rate (the original Q3:2025 release had previously put the corresponding rise in the WPI at 3.4 per cent).

Overall, the annual rate of wage growth remained relatively stable across last year, running at 3.4 per cent in the March, June and December quarters and at 3.3 per cent in the September quarter. On a quarterly basis, the pace of growth moderated slightly from 0.9 per cent in the first half of the year to 0.8 per cent in the second half.

Wages in both the private and public sector also rose 0.8 per cent over the quarter, although on an annual basis, private sector wage growth at 3.4 per cent once again lagged public sector wage growth of four per cent. That marked a fourth consecutive quarter of a gap in favour of the public sector. The ABS said the strong growth in public sector wages across 2025 was due to new state-level public sector wage agreements that delivered multiple pay increases across the year. Those agreements included both backdated increases that took effect soon after the agreement was finalised, followed by a further scheduled rise later in the year.

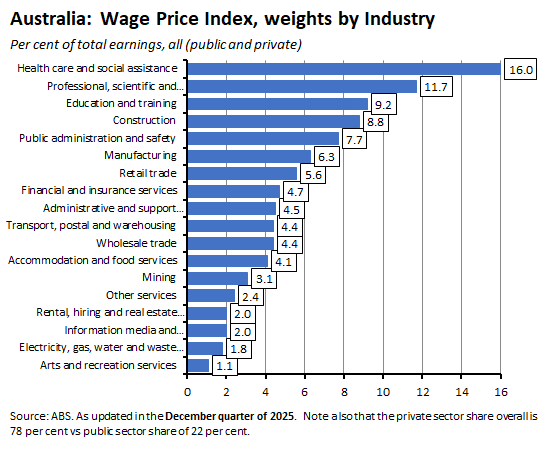

The Bureau said the main contributor to wage growth for both the private and public sectors in the December quarter was the Health care and social assistance industry, where wages were up 1.1 per cent over the quarter and 4.4 per cent over the year. The industry contributed 0.18 percentage points to total quarterly wage growth. That was well ahead of the contribution of the Education and training industry, which made the second largest contribution (0.07 percentage points). The ABS said wage growth in the private sector component of this industry was lifted by Commonwealth funded initiatives in aged care and in early childhood care and education, while growth in the public sector component was largely driven by scheduled enterprise agreement increases paid to NSW healthcare workers.

According to the latest weights for the WPI, the Health care and social assistance industry (public and private together) currently accounts for about 16 per cent of total expenditure on wages, making it the largest contributor to the economy’s wage bill. It accounts for about 12.5 per cent of the total private sector wage bill and 28.5 per cent of public sector expenditure on wages.

But real wage growth went backwards last quarter

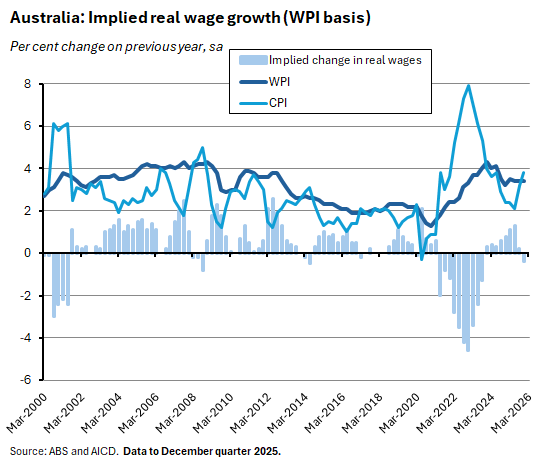

One notable feature of December quarter numbers was the relationship between nominal wage growth and inflation. At an annual rate of 3.4 per cent, growth in nominal wages fell behind the annual increase in the December quarter headline Consumer Price Index (CPI) of 3.6 per cent. That brought to an end a sequence of eight consecutive quarters when wage growth had edged ahead of inflation.

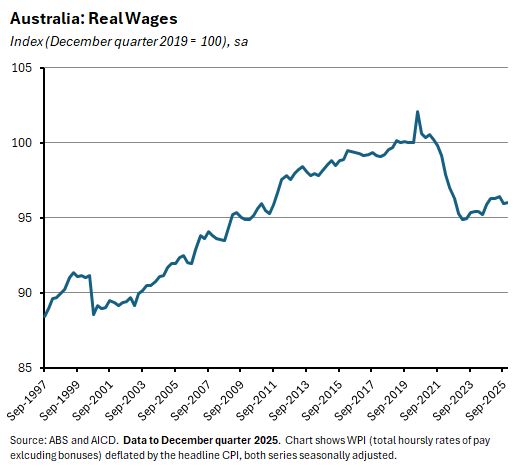

Real wages as captured by the WPI remain well down on their pre-pandemic level (although see the following section on what the WPI measures when it comes to wages vs earnings).

A quick note: Just what is the WPI measuring?

Some readers may have seen the media clip from last week in which RBA Governor Michele Bullock was accused of ‘gaslighting’ Australians as to the state of the economy and real wage growth. Part of that debate involved a discussion as to the relative merits of the WPI as a measure of ‘what people actually earn’.

So, what does the WPI actually measure?

Formally, the WPI measures changes in the price of wages and salaries in the Australian labour market over time. In this way, the WPI is akin to the CPI, in that it tracks changes in the hourly rate paid to a fixed group of jobs, much like the CPI tracks changes in the price of a fixed basket of goods. To achieve this measure of a pure price change, the WPI strips out the effect of compositional changes such as fluctuations in the quality or quantity of work performed or shifts in the structure of the workforce. The headline WPI also excludes bonuses. And by definition, the WPI does not include superannuation.

In contrast, the national accounts measure of average earnings per hour (AENA) is a measure of the average wage bill, covering both changes in the composition of the labour force, along with non-wage payments including allowances, superannuation, and redundancy payments. So, for example, compositional shifts such as a structural rise in the share of higher paying jobs in the labour force, a cyclical increase in the rate of job promotions in a tight labour market, a general upturn in hours worked, or an increase in labour market turnover involving more workers moving to higher paid jobs would all show up as rise in AENA, but by design would not appear as a change in the WPI.

Finally on this topic, note that the RBA tends to think that AENA is a better indicator of broad inflationary pressures in the economy, at least in theory, although in practice it is also a much noisier (more volatile) series than the WPI.

Labour market numbers have no big RBA implications

So, what do this week’s jobs and wage data mean for the RBA and the future trajectory of the cash rate?

Despite that drop in real wage growth, this week’s wage numbers will do little to change the RBA’s view that current labour market conditions remain a little tighter than it is comfortable with. After all, the December quarter numbers told a story that was mostly unchanged from the rest of the year. And at 3.4 per cent, nominal wage growth is still running a bit above where the RBA would like it to be, given our current weak rate of growth in labour productivity.

Recall that last November, we did a deep dive into the September quarter 2025 WPI release and set out the linkages between wages, productivity growth, unit labour costs, and inflation in some detail. In summary, back then we noted the RBA’s decision to pare back its estimate of labour productivity growth over the next couple of years to an annual rate of just 0.7 per cent. One consequence was that Martin Place reckoned the rate of nominal wage growth compatible with inflation at target as measured by the WPI had fallen to around 2.9 per cent.

That said, the step down in the quarterly pace of growth from the first half to the second half of 2025 should offer a degree of comfort. And the nature of the lift from wage growth in the Health care and social assistance industry was also notable, to the extent that it added to the headline rate without directly reflecting underlying labour demand and supply conditions. On balance, then, there was nothing here likely to sound any new alarm bells at Martin Place.

Likewise, the January labour force report was also broadly consistent with the RBA’s recent assessment of labour market conditions. For example, at 4.1 per cent, the unemployment rate remains below the RBA’s estimate of the rate it reckons is compatible with inflation at target. That is usually taken to be around 4.5 or 4.6 per cent, although last year, the RBA’s model-based estimates suggested that the so-called non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) could be a little higher than that, perhaps between 4.6 and 4.8 per cent.

MPB Minutes set out the RBA’s new inflation risk assessment

The RBA published the Minutes of the 2-3 February 2026 Monetary Policy Board (MPB) Meeting this week. The Minutes offer further insight into the RBA’s changed assessment of inflation risk that drove this month’s unanimous MPB vote to increase the cash rate target.

To start with, the minutes discuss the rise in inflation that was the immediate trigger for the decision to tighten policy. The focus here is on how durable that rise would prove, with an emphasis on the role of capacity pressures, including in the labour market:

‘Members discussed the likely persistence of the rise in inflation. They noted that inflation in the second half of 2025 had been broadly based: the share of items in the basket with prices rising by an annualised rate of more than 2.5 per cent had increased sharply and was high by historical standards. The breadth of inflation was consistent with the staff’s assessment that economy-wide capacity pressures – which looked to have increased in the second half of 2025 – had contributed to some of the recent increase.’

At the same time, the Minutes also note that much of the rise in inflation was likely temporary in nature:

‘The staff judged that the larger part of the increase had reflected less-persistent factors, including price volatility in categories such as electricity, travel and groceries, and some sector-specific demand and price pressures that had affected prices of new dwellings and durable goods.’

The RBA’s view of the economic outlook and its increase in forecast inflation reflect the combined impact of several factors: A stronger-than-expected performance in private demand (led by more robust consumption and investment spending); a slight downgrade in the assessment of spare capacity (including a labour market judged to be ‘a little tighter than consistent with full employment’); and evidence of an easing in broader financial conditions, along with signs that monetary policy settings were no longer restrictive.

‘Members noted that inflation had picked up in the second half of 2025 and was currently too high… while the larger part of the increase probably reflected less-persistent factors that would fade over time, some of it was due to underlying inflationary pressure that would be likely to persist with current policy settings. In light of that judgement, the central projection for inflation had been revised materially higher, remaining above target throughout 2026 and only returning close to the midpoint of the target range around mid-2028 (on the assumption that the cash rate follows the market path).’

While the Minutes report that the MPB members did consider the case for leaving the cash rate target unchanged to allow the Board to accumulate more evidence, ultimately, they rejected that argument, since:

‘…members agreed that there was a stronger case to increase the cash rate target by 25 basis points at this meeting. This case rested on their judgements that some part of the rise in inflationary pressures would persist (reflecting greater capacity pressure), that the risks around both the Board’s objectives (price stability and full employment) had shifted, and that financial conditions were currently not restrictive enough to bring inflation back to target within a reasonable period.’

It followed that the Board’s inflation and employment risk assessments had changed:

‘Members also judged that the risks surrounding the Board’s two objectives had shifted materially since the previous meeting, in ways that warranted tighter monetary policy. Regarding risks to meeting the Board’s inflation objective, members emphasised that the staff forecast is for inflation to stay above the midpoint of the target range for at least another two years…if this inflation outlook proved true, it would extend the already long period during which underlying inflation had mostly been above the target range. In relation to risks to the Board’s full employment objective, members agreed that the downside risks to which they had been alert for some time appeared to have abated…the persistent resilience of the labour market reduced their concern about the likelihood of a sharp deterioration in the near term.’

So far, so hawkish.

But the Minutes do also note that the MPB remains unsure about the outlook. As we wrote after the February meeting, at least one more rate increase (likely in May) still looks the most probable outcome. But it is worth noting that a tightening trajectory is not yet fully locked in. Here the Minutes note:

‘…members agreed that the prevailing uncertainties meant it was not possible to have a high degree of confidence in any particular path for the cash rate. They pointed to risks on both sides of the central projection for inflation. If demand growth proved weaker, supply capacity stronger, the pick-up in inflation largely a function of sector specific shocks or the stance of policy more restrictive than believed, then inflation might abate more rapidly than projected. However, if demand growth continued to pick up, supply was more constrained than thought, longer term inflation expectations began to rise or policy was not restrictive, then inflation might prove more persistent than in the central case. Future policy decisions would need to respond to these evolving risks.’

In other words, the RBA remains firmly in data-dependent mode.

Further reading and listening

- The latest IMF Article IV report on the Australian economy. The Fund’s main policy recommendations are to contain price pressures and rebuild fiscal buffers while using structural reforms to target productivity. To that end, fiscal policy should adopt a ‘growth friendly fiscal consolidation’ from FY2026/27, while structural reforms should include corporate tax reform, advancing digitalisation and AI adoption, boosting competition and business dynamism and labour market reforms. One suggested approach to revenue reform, for example, is to increase the GST rate and remove GST exemptions and offset this with changes to corporate income tax settings. The IMF suggests the latter could include an allowance for corporate equity and/or lowering the tax rate, coupled with adjustments to resource rent taxes. The Fund also highlights the importance of fiscal coordination across various levels of government, noting rising state and territory debt. On the productivity front, the Article IV cites several structural headwinds, including the slow pace of adoption of new technologies, fading business dynamism and inefficiency in capital reallocation, which together have manifested in a gap between Australian firms and the global frontier. At the same time, expansion of non-market sectors of the economy has weighed on overall productivity growth. Here, the Fund points to three reform areas it reckons warrant close attention: regulatory compliance costs, skills mismatch and falling innovation.

- The accompanying IMF Selected Issues paper offers a deep dive into Australia’s labour market resilience. The authors caution that the current mix of persistently low unemployment and high vacancies might be overstating the labour market’s cyclical strength, as low unemployment is in part a product of a high job finding rate and strong job retention during the post-pandemic period. But they also note that structural drivers may be keeping labour demand elevated, reflecting some mix of structural and policy changes (expansion in the NDIS and an aging population) and skill shortages. On the supply side of the labour market, they cite strong net migration flows, higher female labour force participation, and increased participation by older and less healthy workers as structural drivers of higher participation while the cost-of-living squeeze has been a cyclical support.

- From the e61 Institute, a review of Australia’s fiscal sustainability.

- Related, the Grattan Institute has some suggestions for this year’s budget.

- Last Friday, the government announced it had appointed Professor Bruce Peston to the RBA’s Monetary Policy Board (MPB) to replace outgoing member Alison Watkins. (Very) short bio at UNSW Business School. Google scholar page. List of Conversation articles. AFR reaction.

- RBA Assistant Governor (Economic) Sarah Hunter gave a speech on defining full employment and its relationship with inflation. She sets out some of the thinking behind the RBA’s judgement that the current labour market ‘remains a bit tight’ and explains the central bank’s evolving approach in its use of NAIRU (non accelerating inflation rate of unemployment) models to assess the labour market. Today, the RBA thinks of these models as estimating the unemployment rate at which current inflation would converge to expected inflation (set at 2.5 per cent, the midpoint of the target range) and then remain stable. In this modified approach, Hunter explains, anchored inflation expectations mean that when the labour market is away from full employment, underlying inflation will be away from target but not necessarily be accelerating away from it. That is, the ‘non-accelerating’ part of NAIRU is now less applicable. Overall, the message is that according to the RBA’s framework, ‘the labour market has stabilised and remains a bit tight…our full employment and inflation objectives are entwined, and the data is painting a complementary picture with a bit too much pressure on both sides.’

- The final report of the Carbon Leakage Review recommends that Australia introduce border carbon adjustment for imports of a small group of commodities, starting with cement and clinker.

- The 60th anniversary of decimal currency in Australia.

- The IMF’s new Article IV Report on China.

- The Economist magazine says Japan’s new prime minister, Takaichi Sanae, is now the world’s most powerful woman.

- Also from the Economist, a warning that the rich world should beware ‘Brazilifcation’, which in this case references the constraints imposed by a high public sector debt service burden.

- The Munich Security Report 2026.

- The first OECD economic survey of the Philippines.

- According to the WSJ, healthcare jobs have become the engine of the US labour market.

- Also from the WSJ, the Chinese approach to managing an AI stock market boom.

- How AI is affecting jobs and productivity in Europe.

- See also Firm data on AI. According to this survey of almost 6,000 CFOs, CEOs and executives across the US, UK, Germany, and Australia, while around 70 per cent of firms actively use AI, 80 per cent of firms report a negligible impact of AI on employment or productivity over the past three years. On the other hand, they predict sizeable impacts over the next three years, including a 1.4 per cent lift to productivity, a 0.8 per cent increase in output and a 0.7 per cent fall in employment.

- A new BIS Bulletin looks at the economic impact of AI in emerging markets.

- From the FT, Martin Wolf’s take on population decline and an optimistic view on life in a depopulating world.

- Also from the FT, why Arctic rivers are turning orange.

- The snowball effect.

- The challenges of working in open-plan offices.

- The Conversations with Tyler podcast talks to Joe Studwell about his new book, How Africa Works. (Studwell’s earlier How Asia Works is a classic).

- Adam Tooze on how to think about the AI boom plus the state of the German economy.

- The FT Economics Show discusses how China is fighting ‘involution’.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content