This week’s meeting of the Reserve Bank’s Monetary Policy Board (MPB) left the cash rate target unchanged and also signalled a shift in the central bank’s risk assessment.

Upside risks to inflation are now front of mind and the debate at Martin Place has shifted decisively. The old question was, would the RBA be able to deliver one final rate cut in the easing cycle early next year? The new question is, will Australia’s central bank now leave rates unchanged for a prolonged period or instead start tightening policy in the first half of 2026? In the words of Governor Michele Bullock, from her post-meeting press conference:

‘I don’t think there are interest rate cuts in the horizon for the foreseeable future. The question is, is it just an extended hold from here or is there possibility of a rate rise? I couldn’t put a probability on those but I think they’re the two things that the Board will be looking closely at coming into the new year.’

One way to think about this is in terms of two views on what recent inflation numbers tell us. The first is that some elements of inflation are proving disappointingly persistent, making the return to target take longer than the RBA is comfortable with. That would argue for the governor’s ‘extended hold’ option. The second is that the spike upwards in recent inflation readings signals that inflation is not just proving more persistent, but that this persistence is broad based and that inflation may even be at risk of re-accelerating as the economy hits its speed limit. A near-term rate increase would be the appropriate response in this case.

For now, all this leaves any case for a future cut reliant on a negative shock to activity, perhaps from adverse developments in the global economy. But the MPB’s view is that such downside risks have abated, even asinflation risk has increased.

One note of caution. In the RBA’s data-dependent world, we have already seen how market expectations about the future path for rates can swing quite quickly as additional information becomes available. After all, the current shift in market sentiment largely reflects one quarterly and one monthly inflation reading. Tracking the data flow will continue to be important, and this week’s release of the November labour force numbers serve as a timely reminder of this point. While the unemployment rate was unchanged last month - despite consensus forecasts for a slight increase - the underemployment rate rose by 0.4 percentage points. At the same time, employment fell by more than 20,000, despite market expectations for positive job growth. That indicates a modest degree of labour market weakening, although not enough to materially alter the MPB’s analysis of the current balance of risks.

We dig deeper into the MPB’s latest thinking below, review this week’s labour market release in a bit more detail and provide the usual selection of further reading and listening.

The MPB is likely to debate the case for a rate hike next February

As noted above, the RBA’s Monetary Policy Board (MPB) voted unanimously this week to leave the cash rate target unchanged at 3.6 per cent. That decision was widely expected by markets, which meant that once again this was another meeting where most of the anticipation involved messaging around the decision, rather the decision itself. RBA-watchers were particularly keen to see whether the MPB would signal a shift to a more hawkish outlook for policy. The backdrop here was October’s uncomfortably high reading from the new monthly CPI, which put headline inflation well above target at 3.8 per cent and underlying inflation at 3.3 per cent.

In that context, MPB did sound more hawkish this week, albeit paired with its usual caution around reading too much into a small sample of recent data points. Consider the second paragraph of this week’s short statement by the Board:

‘While inflation has fallen substantially since its peak in 2022, it has picked up more recently…some of the recent increase in underlying inflation was due to temporary factors and there is uncertainty about how much signal to take from the monthly CPI data, given it is a new data series. Nevertheless, the data do suggest some signs of a more broadly based pick-up in inflation, part of which may be persistent and will bear close monitoring.’

Similarly, according to the penultimate paragraph:

‘The recent data suggest the risks to inflation have tilted to the upside, but it will take a little longer to assess the persistence of inflationary pressures. Private demand is recovering. Labour market conditions still appear a little tight but further modest easing is expected. The Board therefore judged that it was appropriate to remain cautious, updating its view of the outlook as the data evolve.’

So, the MPB (1) acknowledged that inflation has picked up, (2) thinks a portion of that increase is broad-based and could prove persistent, and (3) now judges the risks to inflation are tilted to the upside.

Governor Bullock’s press conference following the MPB meeting further reinforced these messages, using language that was more hawkish than the preceding statement. Responding to the opening question, she explained that the board ‘didn’t consider the case for a rate cut at all’ at this week’s meeting, and added that although the MPB ‘didn’t explicitly consider the case for a rate rise…we did consider and discuss quite a lot the circumstances and what might need to happen if we were to decide that interest rates had to rise again at some point next year.’

In response to further questions, the Governor indicated that another rate cut was no longer on the cards:

‘I would say at this moment that given what’s happening with underlying momentum in the economy, it does look like additional cuts are not needed.’

She explained that this reflected a shift in the Board’s risk assessment:

‘The Board does think that relative to six months ago or seven months ago, a lot of the downside risks seemed to have abated a bit and some of the upside risks seem to have been generated.’

All that said, the MPB did remain cautious about just how much weight to place on both the September quarter’s result and the monthly October print. In the case of the former, the Governor noted there were some mixed messages in the data, commenting that ‘there’s enough in the quarterly inflation print to suggest that there is some persistence there, but there’s also a bit to say, there was a whole lot of random things that just went up and maybe they’re not going to go up again at the same rate’. In the case of the latter, she reminded her audience (in line with our comments at the time) that ‘We don’t know how the monthly numbers are going to play out yet because it’s a new series. They’re volatile. They’re not seasonally adjusted in a way that they normally would be with a long series of data. And the other thing is we don’t know how the series behaves.’

The MPB next meets on 2-3 February 2026. At which point the Board will hope to be better placed to decide whether the signal that the September quarter data sent on underlying inflation was ‘just a whole lot of unrelated one-off factors’ or whether it was ‘demonstrating that there are underlying capacity pressures in the economy’.

Labour market shows modest signs of weakening

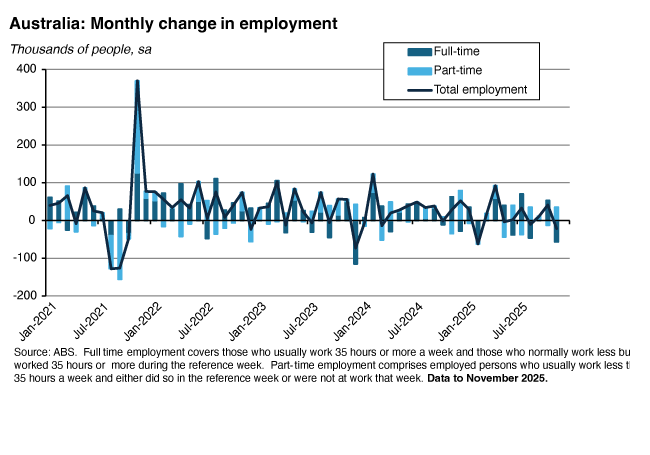

The ABS said the number of employed people in Australia in November 2025 fell by 21,300 (seasonally adjusted) over the month. A 56,500 drop in full-time employment drove the decline, only partially offset by a 35,200 increase in part-time work.

That result was much weaker than the market consensus forecast, which had expected a 20,000 increase for last month.

Both the participation rate (down from 66.9 per cent to 66.7 per cent) and the employment to population ratio (down from 64 per cent to 63.8 per cent) also declined in November.

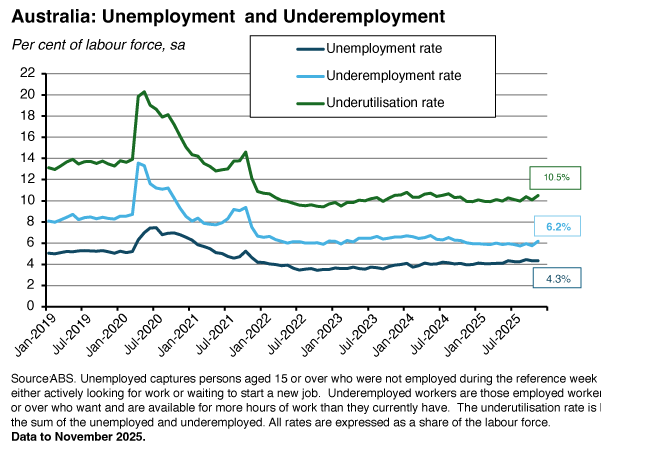

The seasonally adjusted unemployment rate was unchanged at 4.3 per cent. Here, the consensus forecast had predicted a modest rise to 4.4 per cent. The underemployment rate did increase, however, rising from 5.7 per cent to 6.2 per cent, its highest rate since October last year. As a result, the overall underutilisation rate increased to 10.5 per cent, its highest rate since August 2024.

Overall, November results suggested a modest degree of easing in the labour market. They also follow a strong October reading (and before that a weak September result) and as such reinforce the point we made last month about the volatility in recent monthly outcomes.

Other Australian data points to note

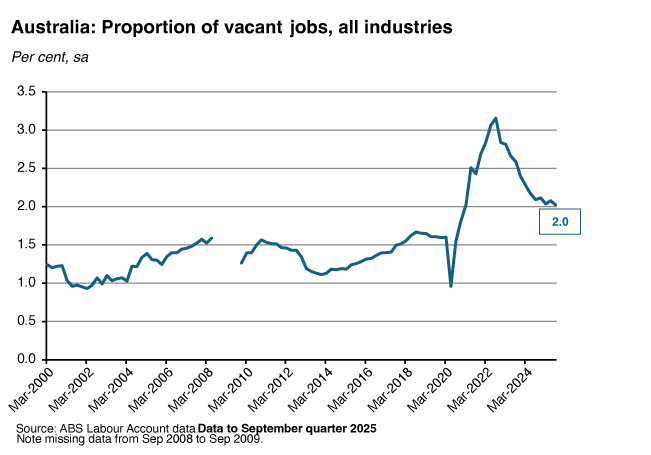

Last Friday, the ABS released the Labour Account for the September quarter 2025. The number of filled jobs rose by 107,600 (0.7 per cent) over the quarter to 16.1 million, with main jobs up 67,300 (0.5 per cent) and secondary jobs rising 40,300 (3.8 per cent). In annual terms, growth in filled jobs was just 1.2 per cent, which the Bureau noted was the slowest annual result since the March quarter 2021. The number of job vacancies fell 1.9 per cent over the quarter and was down two per cent over the year, with vacancies falling in 13 out of 19 industries over the quarter. The vacancy rate fell back to two per cent.

ABS data on Industrial Disputes in the September quarter 2025 reported a total of 216 disputes over the year, involving more than 89,000employees and with more than 151,000 working days lost.

ABS estimates of Industrial Level KLEMS (capita, labour, energy, materials, and services) Multifactor Productivity. The estimates are for the 16 market sector industries and cover 2023-24.

The ABS Water Account for Australia, for the 2023-24 financial year.

Further reading and listening

- The ABS lists 10 things that happened in the Australian economy during the previous quarter.

- The December edition of the RBA’s chart pack.

- Andrew Shearer, Director General of National Intelligence, on Australia’s geopolitical challenges.

- The Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) presents its 2025-26 National Fiscal Outlook, which consolidates forecasts from state and territory budgets with the Commonwealth fiscal accounts. According to the PBO, the national fiscal outlook has worsened since the previous year’s assessment, ‘reflecting a deterioration in aggregates across most jurisdictions’. The PBO said this deterioration is due to increases in forecast expenses that exceed projections of increased revenues in each jurisdiction. Its scenario analysis also finds a weaker long-term fiscal sustainability outlook compared to its 2024 report. Even so, the PBO still judges that the national fiscal position is likely to remain sustainable, provided growth in expenses falls more into line with growth in revenues.

- From the e61 Institute, is Australia set to be Data Central? The author sounds a note of caution over the direct implications of data centre investment for Australian growth – much of their value is imported, the post construction employment footprint is small and they could compete for other sectors for energy – arguing that ‘the bigger prize potentially lies in how much domestic data centre investment can be leveraged to help unlock Australia’s digital infrastructure and encourage digitisation among individual firms’.

- The CEO of the Grattan Institute warns that Australia’s policy reform clock is ticking and suggests a list of policy changes, including a gradual reduction of the capital gains tax discount on housing, scaling back superannuation concessions, and (at the state level) unlocking greater housing density in the inner suburbs of Australian cities.

- The 2025 US National Security Strategy (NSS). A view from ASPI offering an Australian perspective, the FT’s Gideon Rachman on why the NSS makes for uncomfortable reading in Europe. A take from the European Council on Foreign Relations. And in the WSJ, Walter Russel Meade offers a different perspective again with a focus on the ‘Trump Corollary’ to the Monroe Doctrine.

- Some thoughts on the implications of China’s record US$1 trillion trade surplus.

- A revised and expanded edition of the CEPR’s e-book on the economic consequences of the Second Trump administration. A summary column argues that the direction of travel is now clear – a world with higher trade barriers, weaker institutions and more fragile growth.

- Related, and also from the CEPR, The narrowing path: Trade and development in a new era. According to the authors, ‘…the export-led growth miracles of recent decades reflected a unique historical moment that has ended. While trade will remain an important source of growth, developing countries now face a substantially more constrained environment where replicating past successes will be harder and more conditional on major powers' strategic choices.’

- The December 2025 BIS Quarterly Review analyses market performance over the September to November period of this year, contrasting markets’ risk-on mood with mounting challenges from market volatility, policy uncertainty, growing unease about a possible economic slowdown, and concerns about stretched equity market valuations.

- Also from the BIS, a new Bulletin on the implications for monetary policy of the rise of non-bank financial institutions.

- The FT’s Martin Wolf explains why the world should worry about stablecoins.

- For a second year running, a southern European country tops the Economist magazine’s economy of the year list. Portugal gets number one spot this time, after Spain won in 2024. Australia ranks 18th out of the 36 ‘mostly rich’ countries scored by the magazine.

- Three new reports from the OECD. First, a decade of OECD competition trends, data and insights. This looks at trends in global competition enforcement – including merger activity, antitrust enforcement and resources and institutional setting – over the years from 2015 to 2024. Second, the OECD Skills Outlook 2025, which ‘examines how countries can build the 21st century skills needed to sustain growth and social progress’. And third, Revenue Statistics 2025 which reports data on tax revenues in OECD countries. The average tax-to-GDP ratio of OCED members increased to 34.1 per cent in 2024, its highest level on record.

- The WSJ speculates as to how a Chinese invasion of Taiwan might unfold.

- The December edition of the IMF’s Finance and Development magazine focuses on the era of big data.

- The top 10 archaeological discoveries of 2025.

- This Sinica podcast from last month discusses the Nexperia dispute, which make for a useful case study for the current geoeconomic contest over semiconductor supply chains.

- Bloomberg’s Big Take podcast on why we can’t quit Microsoft Excel, and what AI might mean for the ubiquitous spreadsheet.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content