Unsurprisingly, possible implications of the war between Israel and Iran dominated much of the past week’s economic and financial news and analysis. Equally unsurprisingly, much of the focus was on potential consequences for the oil price and what an oil shock would do to an already-shaky international economic outlook.

What has surprised at least some observers has been relatively modest moves in market prices in response. We dig into shifting assessments around the risk of an oil price spike and its effects below. We also take a look at this week’s Australian labour market numbers, which combined a fifth successive month of an unchanged 4.1 per cent unemployment rate with weaker-than-expected employment numbers. And we check in on the Treasurer’s speech to the National Press Club on economic reform.

Finally, many thanks to those of you who were able to attend this week’s economic briefing either in person or online. I hope you found it interesting.

Oil price risk, again

Intensified conflict between Israel and Iran is once again raising fears that the global economic outlook will be vulnerable to an ‘oil shock’ originating in the Middle East. To date, the oil price response to the war has been relatively modest. After an initial spike, prices have retreated somewhat. Financial markets more broadly have also been fairly sanguine, at least so far. But will that last?

We previously considered the implications of an oil price shock triggered by conflict in the region in our 4 October 2024 update. Back then, we made the point that the historical record told us two things.

First, that regional conflicts have all been associated with varying degrees of disruption to the global oil market. These include the 1956-57 Suez Crisis, the 1973-74 Arab oil embargo in response to the Yom Kippur War, the 1978-79 Iranian Revolution, the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war, the 1990 Iraq invasion of Kuwait and the first Gulf War, the 2011 Libyan civil war, the 2019 attacks on Saudi oil facilities and the levying of sanctions on Iran, and most recently the period of turmoil instigated by the October 2023 Hamas attack on Israel. On at least two occasions in the 1970s, resultant economic fallout was substantial, manifesting in lower growth and higher inflation and arguably contributing to the international economic regime change that ended the Keynesian era and replaced it with a new Neoliberal settlement.

But second, that same historical record shows no simple, mechanical relationship between an oil shock and global economic outcomes. Similarly-sized supply shocks have generated considerably different degrees of economic disruption. That is because the economic consequences are determined by a broad range of variables that go beyond the size and duration of any direct disruption to supply to encompass additional supply-side factors, including the availability of alternative sources of supply (oil production today is much less reliant on the Middle East than it was back in the 1970s, for example. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that the United States has accounted for 90 per cent of oil supply growth worldwide over the past decade) and the ability and willingness of countries to deploy strategic reserves (one lesson of those disruptive 1970s oil shocks was the advisability of building stockpiles). Demand factors are critical too, including the global economy’s shifting reliance on oil (again, the oil intensity of world production has fallen significantly since the 1970s oil shocks), the cyclical state of global growth and the consequent strength of global oil demand (the IEA estimates that 60 per cent of the rise in global oil demand over the last 10 years came from a Chinese economy that is now demonstrating quite different demand dynamics).

So, how do current risks stack up against those metrics?

Start with the likely size of any supply disruption. According to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA)’s latest (October 2024) assessment of Iranian energy, Iran accounts for around 24 per cent of all Middle East oil reserves and about 12 per cent of the global total. (Iran is also one of the world’s largest dry natural gas producers, behind only the United States and Russia in 2022, and has the second largest estimated proved natural gas reserves in the world at about 16 per cent of the global total. Much of Iran’s gas production is consumed at home, with exports going to neighbouring countries, primarily Iraq and Türkiye, via pipelines). The combined impact of years of underinvestment and US-led international sanctions mean that Iran’s oil production and exports are both considerably lower than might otherwise be implied by its ample reserves. For example, according to the IEA’s June 2025 Oil Market Report, Iranian exports of crude oil and condensates have averaged around 1.7 million barrels per day (mb/d) this year. That compares to the IEA’s forecast for world oil demand in 2025 of around 103.8 mb/d. In other words, Iranian exports currently meet less than two per cent of global demand, limiting the economic impact of a supply disruption. Strikingly, nearly all those exports head to China (the EIA reckons that China was the destination for 89 per cent of Iran’s crude oil and condensate exports in 2023, with most of the crude destined for use in small, independent ‘teapot’ refineries that aren’t state-owned).

That means most concerns around a large supply disruption must go beyond the immediate risks to Iranian exports to generate large price moves. One risk is that the conflict broadens and inflicts widespread damage to the energy infrastructure of other Middle East oil producers, for example. Another is that it results in disruption to the Strait of Hormuz, as in the past Tehran has repeatedly threatened to close the Strait if attacked. According to the EIA, the Strait, located between Oman and Iran and connects the Persian Gulf with the Gulf of Oman and the Arabian Sea, is one of the world‘s most important oil chokepoints. Last year, oil flow through the Strait averaged 20 mb/d and accounted for more than one quarter of total global seaborne oil trade and about 20 per cent of global oil and petroleum product consumption. Supply from Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Kuwait, Iraq and Iran and most of the world’s spare production capacity is heavily reliant on this route. In addition, about 20 per cent of global LNG trade also transited the Strait in 2024, mainly from Qatar. Asian consumers are particularly exposed: The EIA estimates that 84 per cent of the crude oil and condensate and 83 per cent of the LNG that passed this way went to Asian markets, primarily China, India, Japan, and South Korea.

Despite some headline stories – including a tanker collision near the Strait of Hormuz – at the time of writing, there had been no significant impact on the movement of vessels through the Strait. That said, the FT has reported a jump in insurance costs, saying prices have risen more than 60 per cent since the start of the war between Israel and Iran, rising from 0.125 per cent of the value of the ship to about 0.2 per cent. It also reported that prices to charter large oil tankers sailing through the Strait have more than doubled.

Next, what about the availability of other sources of supply, and the overall balance between supply and demand in the oil market? The IEA’s June 2025 Oil Market assessment reckons that in the absence of a major disruption – oil markets look ‘well supplied'. As already noted, the IEA forecasts world oil demand to increase by a relatively modest 720kb/d this year to 103.8mb/d, reflecting subdued world activity (recall all those downgrades to global growth we highlighted last week). In contrast, it thinks global oil supply will rise by a much larger 1.8mb/d to 104.9 mb/d as non-OPEC+ producers alone add 1.4 mb/d of production. Moreover, with supply currently running ahead of demand, the IEA says global oil inventories have risen by 1mb/d on average since February this year, jumping by a ‘massive’ 93mb in May alone.

Given this context, the relatively limited market price reaction seen to date is explicable. Even so, the world should not be too complacent. If the conflict persists, the risk of a larger impact on oil prices and on economic conditions more broadly will increase. As will concerns about broader global disorder and geopolitical risk.

Australia’s unemployment rate steady at 4.1 per cent

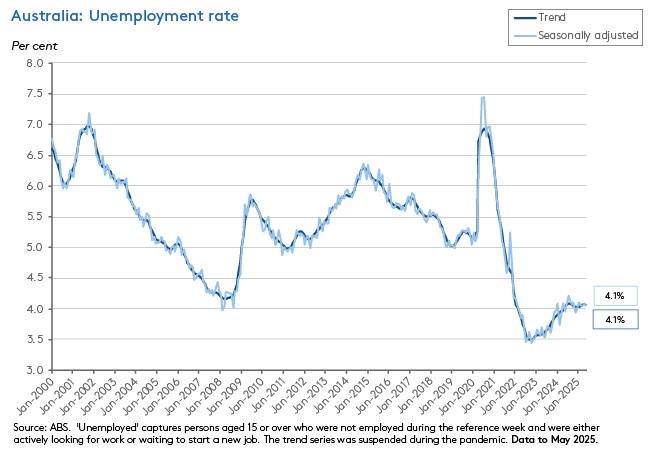

The ABS said that in May this year Australia’s unemployment rate remained at 4.1 per cent (seasonally adjusted) for a fifth consecutive month. The outcome was in line with market expectations, as the trend unemployment rate also printed at 4.1 per cent for a third consecutive time.

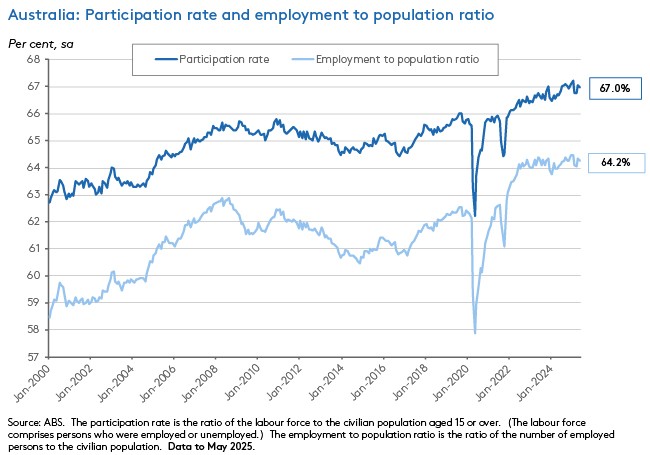

The underemployment rate ticked down from six per cent in April to 5.9 per cent last month as the number of monthly hours worked in all jobs rose 1.3 per cent over the month and 3.1 per cent over the year. The Bureau said the monthly jump in hours worked reflected payback from the previous two months’ readings, when hours had been pushed down by the Easter holidays and severe weather disruption.

The overall labour market underutilisation rate fell from 10.1 per cent to 9.9 per cent.

May’s stability in the unemployment rate came despite a 2,500 fall in the number of employed. That reflected a drop of 41,100 in part-time employment that more than outweighed an increase of 38,700 in full-time employment. The decline in employment was a much weaker result than the consensus forecast, which had anticipated a 21,200 increase.

The impact of the fall in employment on the unemployment rate was offset by a 0.1 percentage point drop in the participation rate to 67 per cent, as the number of unemployed also fell. The employment to population ratio also slipped last month, dropping from 64.3 per cent in April to 64.2 per cent in May.

The Treasurer on Economic Reform

Treasurer Jim Chalmers gave an address to the National Press Club this week on economic reform in the government’s second term. Echoing a key theme of last week’s note, the Treasurer declared productivity is now the government’s primary focus. He highlighted four key problems, declaring:

- The Australian economy is not dynamic or innovative enough

- Private investment rates have so far failed to deliver sufficient capital deepening (a rise in the capital-labour ratio)

- Skills are not abundant enough or appropriately matched to business needs; and

- Australia’s changed industrial bases and the growth in services makes productivity both harder to find and harder to measure.

The government’s policy response to this agenda is based around the so-called ‘Five Pillars’ of productivity and according to Chalmers, it has already made ‘substantial progress on all of them’. He reckons that in its first term, announced reforms responded ‘to about two-thirds of the directives in the Productivity Commission’s 2023 Five-year review.’ And the Commission’s interim report on the Five Pillars will now serve as a key input into the planned Productivity Roundtable scheduled for 19-21 August 2025.

In its second term, the Treasurer indicated the government will seek to make progress on National Competition Policy, including by abolishing non-compete clauses for most workers, introducing national occupational licensing and adopting safe overseas standards to reduce regulation. In addition, he acknowledged that ‘Better regulation, cutting red tape without lowering standards, has an important role to play as well.’

Alongside productivity, Chalmers’ speech also highlighted the challenges to budget sustainability raised by six structural budgetary spending pressures linked to health, the NDIS, aged care, early childhood education and care, defence, and interest costs. At the same time, the Treasurer noted that on the revenue side of the fiscal accounts, an ageing population and the global net zero transition were also reshaping the tax base.

In the context of a quest for productivity, resilience and budget sustainability, Chalmers conceded that ‘No sensible progress can be made…without proper consideration of more tax reform’ and said that August’s upcoming reform roundtable would be ‘about shaping the direction for long term economic reform…setting out some guiding reform principles and next steps to advance the agenda…find common ground if it exists.’

He set out three preconditions for contributions to the future reform debate:

- They should address the national interest, rather than state, sectoral or vested interests.

- Ideas should be budget neutral at a minimum but preferably budget positive overall.

- And proposals should be specific and practical.

There were also a couple of additional interesting points that emerged from the Q&A session that followed the speech.

First, with regard to the precondition that reform ideas should be at minimum budget neutral and preferably budget positive, the Treasurer explained this should not rule out cuts to spending, saying he hoped ‘people come to this discussion, not just with ideas about improving the revenue base, but also about where government spending is not giving us the dividends or the returns that we need…it’s possible that people will come to the discussion with an idea to invest more over here, or to provide tax relief over here, which is not necessarily paid for by higher taxes, but might be paid for by less spending’.

Second, although the Treasurer explicitly said he didn’t want to pre-emptively rule out any ideas, when asked about looking at changes in the GST to deliver more revenue, he did not sound particularly enthusiastic. ‘I think it’s hard to adequately compensate people. I think often an increase in the GST is spent three or four times over by the time people are finished with all of the things that they want to do with it…I’m going to try not to dismiss every idea that I know that people will bring to the roundtable. I suspect the states will have a view about the GST. It’s not a view that I’ve been attracted to historically. But I’m going to try not to get in the process of shooting ideas between now and the Roundtable.’

Finally, the Treasurer explained that the increased emphasis on productivity including the upcoming August Productivity Roundtable were ‘all about testing the country’s reform appetite’, including by ‘explaining why…trade-offs are important and why they might be necessary’, since ‘reform succeeds when you can bring people with you. It requires courage, but it requires consensus as well.’

I’ve argued elsewhere that longer parliamentary terms might help, too.

What else happened on the Australian data front this week?

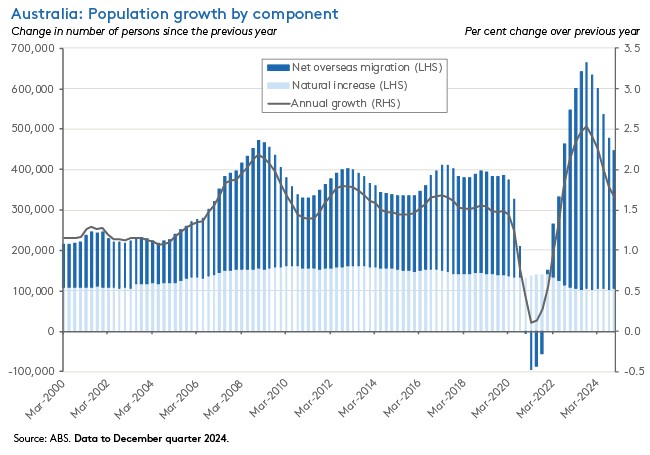

The ABS said Australia’s estimated resident population (ERP) was 27.4 million at 31 December 2024. That was up 1.7 per cent or 445,900 people over the year. Annual natural increase was 105,200 while net overseas migration was 340,800.

The ANZ-Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence Index fell 1.3 points to 85.4 in the week ending 15 June 2025. Four of the five subindices registered falls, led by a 2.1-point drop in ‘medium term economic confidence’ and a two-point decline in ‘time to buy a major item’. ‘Future financial conditions’ fell 1.6 points and ‘Current financial conditions’ declined by one point, with only the ‘short-term economic confidence’ subindex unchanged. ANZ said the decline could reflect escalating geopolitical uncertainty associated with conflict in the Middle East. Higher inflation expectations – up 0.2 percentage points to 4.9 per cent – could also have been lifted by conflicted-related concerns about higher energy prices.

Other things to note . . .

- The Actuaries Institute has released a new report on Housing in Australia, which argues Australia faces ‘a paradoxical dual housing crisis: rising house prices relative to wages in metropolitan areas create intergenerational inequity while climate-driven price declines in high-risk regions create geographic inequity’. According to the Institute, while home ownership among 25 to 34-year-olds has fallen from more than 50 per cent to just 37 per cent over two decades, at the same time approximately 15 per cent of Australian households (1.6 million) experience extreme home insurance affordability stress – concentrated in climate-vulnerable regions.

- The 2025 edition of the Lowy Institute Poll finds that Australians’ trust in the United States has fallen sharply, dropping by 20 points from 2024 and down to its lowest level in the history of the survey. Meanwhile, Australians also remain wary of China. On the economy, only 52 per cent of respondents say they feel optimistic about Australia’s economic performance over the next five years. That is equal to the COVID-era low reported in 2020.

- David Jacobs, the RBA’s Head of Domestic Markets, gave a speech on Australia’s Bond Market in a Volatile World. Jacobs noted that, despite an ‘extraordinary decline in Australia’s net foreign liabilities in recent years’, the Australian bond market has continued to grow in a context of domestic investors accumulating foreign assets (especially equity) even as foreign investors have wanted to hold Australian debt. Looking ahead, Jacobs highlights challenges posed by increasing competition for global capital (sometimes characterised as an emerging global ‘bond glut’) and the potential for spillover effects from period market disruptions (such as those associated with the 2 April 2025 ‘Liberation Day’ tariff announcements).

- The AFR’s Michael Read says superannuation tax concessions need reform but that the government’s current proposals are not the answer.

- Grattan’s Aruna Sathanapally on how the world of work is being transformed.

- The Department of Industry, Science and Resources’ AI Adoption Tracker says 40 per cent of Australian small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are currently adopting AI, while 38 per cent are not planning to implement AI over the next 12 months.

- The ABS presents seven facts about Australia’s horticulture and livestock.

- Already cited above, according to the IEA’s Oil 2025, beyond the immediate risks to energy security, the medium-term outlook will see increases in global oil supply far outpace demand growth.

- Perhaps counterintuitively, FT Alphaville says while financial volatility may be up, actual economic volatility is down – ‘the degree of stability in the global economy is probably unprecedented’.

- The Economist magazine’s Buttonwood column argues investors are often right to ignore world-changing news such as the war between Israel and Iran.

- Also from the Economist, why today’s graduates are screwed. Graduate unemployment is rising, the university wage premium is shrinking and jobs are reportedly less fulfilling.

- PNG’s IMF Article IV According to the Fund, Australia’s neighbour to the North remains in a fragile state, with macroeconomic and social stability at risk. A decade of shocks (low commodity prices, severe droughts, earthquakes and the COVID-19 pandemic) have harmed growth, contributed to persistent foreign exchange shortages, and pushed up public debt.

- The WSJ explains why the US Fed isn’t cutting rates despite slowing inflation. Concerns over inflation expectations are at the heart of the story.

- Making sense of (US) recession probabilities.

- From the OECD, the Global Drought Outlook says the global land area affected by drought has doubled since 1900, with 40 per cent of the planet now experiencing more frequent and intense events.

- How one Kiwi tamed inflation.

- Two Big Reads from the FT. One asks why Big Tech is unable to reach agreement on Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), while the second considers why the world cannot quit coal.

- And the FT on the best books of the year so far.

- McKinsey analyses how shifts in trade corridors could affect business.

- On the persistent allure of autarky.

- Why everything becomes more complex.

- The anatomy of the spy novel.

- Michelle Grattan talks to Treasurer Jim Chalmers.

- The Odd Lots podcast talks to Trump economic advisor and Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers Stephen Miran.

- The Conversations with Tyler podcast hosts Chris Arnade on walking (in) cities.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content