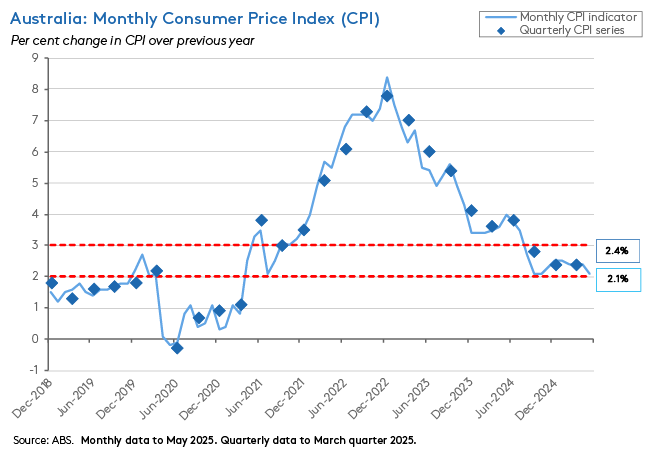

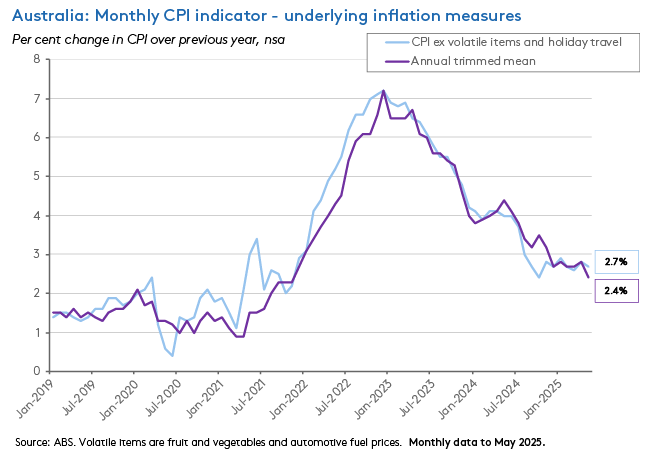

The annual rate of inflation as measured by the Monthly Consumer Price Index (CPI) Indicator fell to just 2.1 per cent in May this year, down from 2.4 per cent in April. Underlying inflation was markedly lower too, with the annual rate of increase in the monthly version of the trimmed mean slowing to 2.4 per cent from 2.8 per cent in the preceding month. On this basis, underlying inflation is now back at a rate last seen in late 2021.

When the April 2025 monthly result saw inflation go sideways, we argued at the time there was nothing there to push the case for an ‘early’ RBA rate cut at the upcoming 8 July Monetary Policy Board (MPB) meeting. In contrast, the pickup in the pace of disinflation reported in the latest monthly reading does have strong, positive implications for the probability of another 25bp dose of policy easing next month. Indeed, market pricing at the time of writing suggests that a cut is now pretty much nailed on.

But we wouldn’t go quite that far. After all, we know from past RBA comments that Australia’s central bank is careful about placing too much weight on what it sees as the ‘very volatile’ monthly Indicator. From Governor Bullock’s perspective, the RBA only gets ‘four readings on inflation a year’ with monthly readings offering only supporting evidence. So, there is still an argument for caution. Even so, the case for the MPB choosing to wait for (say) the August meeting to deliver another rate cut has now weakened appreciably. Put that together with the soft first quarter GDP reading (which prompted us to argue that the July meeting should be treated as ‘live’) and a rate cut next month now seems an increasingly likely outcome.

On balance, recent developments in the Middle East also help this case. Elevated uncertainty implies downside risks to activity. And while the durability of the ceasefire between Iran and Israel remains unpredictable, the initial impact has been to unwind much of the previous run-up in the oil price, removing – at least for now – one inflation item from the MPB’s worry list.

Meanwhile, the current pause in the conflict should not obscure the bigger picture story about elevated levels of geopolitical uncertainty risk of state-on-state conflict. As well as providing yet another expectations-related headwind for private sector activity, a second important implication of this environment is continued upward pressure on governments to ramp up defence spending. Thus this week also saw the United States’ NATO allies pledging to meet a Trump administration demand that they increase defence spending to five per cent of GDP by 2035. That promise comprises targets for ‘core defence’ spending of 3.5 per cent of GDP plus 1.5 per cent of GDP in related infrastructure. History suggests that – to the degree such intentions are met – the consequences will include bigger government deficits and more public debt.

After a deeper dive into this week’s price data, we examine the economic implications of this new geopolitical environment in more detail below, along with the regular data and linkage roundups.

Monthly CPI Indicator reports price pressures easing

The ABS said the Monthly Consumer Price Index (CPI) Indicator rose 2.1 per cent over the year to May 2025. That was down on April’s 2.4 per cent result, below the consensus forecast of a 2.3 per cent print and marked the lowest reading since October last year. It also means that on this basis, inflation has now had a ‘two’ in front of it for 10 consecutive months.

The monthly data also reported encouraging progress with disinflation in terms of underlying inflation. The annual rate of increase in the CPI excluding volatile items (that is, excluding Fruit and vegetables and Automotive fuel) eased from 2.8 per cent in April to 2.7 per cent in May. More dramatically, the Annual trimmed mean slowed from 2.8 per cent to 2.4 per cent over the same period. The latter is the lowest rate of trimmed mean inflation reported since November 2021.

According to the Bureau, five of the 11 groups that comprise the basket of goods and services that make up the monthly Indicator reported a slowdown in their annual rate of price increase last month when compared to April:

- Food and non-alcoholic beverages inflation slowed from 3.1 per cent in April to 2.9 per cent in May, with the ABS highlighting lower prices for fruit and vegetables, including for mandarins, oranges, avocados, and apples.

- Housing eased from 2.2 per cent to two per cent as rental growth slowed from five per cent in April to 4.5 per cent in May, which is the lowest reported rise in rental prices since December 2022. There was also a slowdown in the rate of price increase for new dwellings, which dropped from 1.2 per cent in April to 0.8 per cent in May and marks the lowest rate of growth since April 2021 as project home builders offered discounts and other promotional offers. Electricity prices also continued to fall on an annual basis, although the rate of decline eased from 6.5 per cent in April to 5.9 per cent in May, reflecting a smaller impact of Commonwealth Energy Bill Relief Fund (EBRF) rebates, due to the timing of payments in Victoria.

- Furnishings, household equipment and services edged down from one per cent to 0.9 per cent.

- Recreation and Culture inflation dropped from 3.6 per cent to 1.4 per cent as the rate of increase in Holiday travel and accommodation prices tumbled from 5.3 per cent in April to just 0.6 per cent in May. The main driver was domestic holiday travel and accommodation, which saw a fall in demand after the Easter and school holidays.

- Insurance and financial services fell from four per cent to 3.1 per cent as annual growth in insurance prices slowed to 3.9 per cent in May from 7.6 per cent in April, largely reflecting a slowdown in house and motor vehicle insurance. The rate of annual insurance increases is now well down from the 16.5 per cent peak reached in April last year.

In addition, disinflation persisted in the Transport group last month. Prices fell 2.5 per cent over the year, pulled down by a 10 per cent drop in Automotive fuel prices due to lower global oil prices. Automotive fuel prices are now at their lowest level since September 2022 as the average price for unleaded petrol across capital cities has fallen from a peak monthly average of $2.07 per litre in September 2023 to $1.73 per litre in May 2025.

Of the remaining five groups, the annual rate of inflation was little changed in Education (5.7 per cent) and Health (4.4 per cent) and only picked up in three: Alcohol and tobacco (up from 5.7 per cent to 5.9 per cent), Clothing and footwear (up from 0.8 per cent to 1.3 per cent) and Communications (up from 0.7 per cent to one per cent).

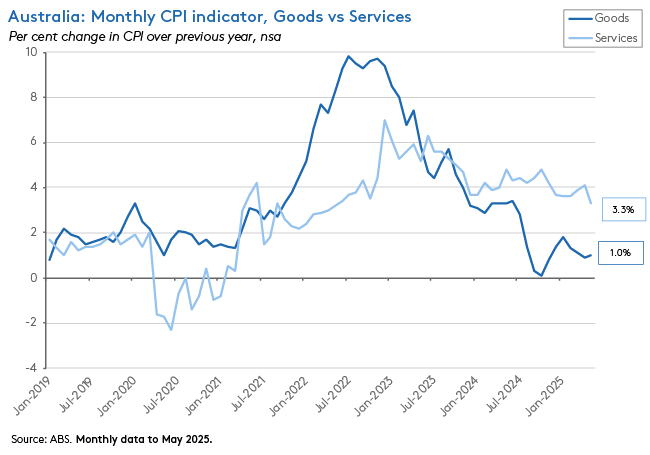

By broad analytical category, the rate of services inflation slowed from 4.1 per cent in April to 3.3 per cent in May, while goods inflation ticked up from 0.9 per cent to one per cent over the same period. Tradables inflation slowed from 0.3 per cent in April to almost nothing in May, while non-tradables inflation moderated from 3.6 per cent to 3.2 per cent.

The rise of state-on-state conflict, geopolitical risk and defence spending

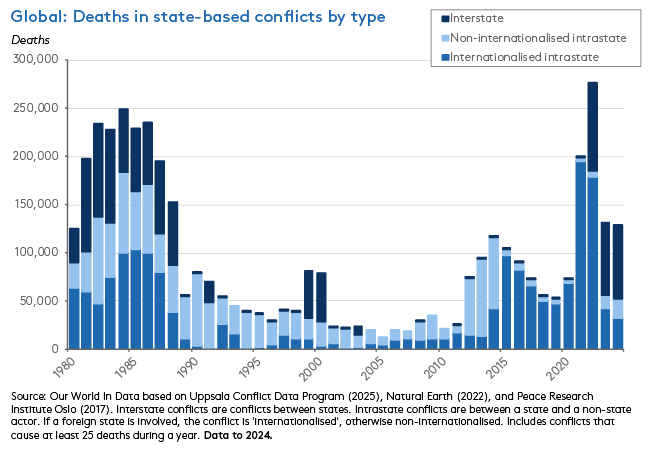

Last week’s note spent some time explaining the relatively modest scale of the oil price reaction to the Iran-Israel conflict. Subsequent developments and a ceasefire that was still holding at the time of writing suggests that the oil market got it right, at least so far. But aside from immediate economic concerns around the potential consequences for energy prices, growth and inflation, the ‘12-day war’ is also part of a broader trend that overshadows the world economy. As the World Bank highlights in its latest Global Economic Prospects (GEP), ‘The incidence of armed conflicts has risen substantially in recent years…the risk of continued or escalating conflict remains high – both at the interstate and intrastate level – against a backdrop of elevated geopolitical tensions globally.’ This month’s war in the Middle East follows clashes between India and Pakistan earlier this year and the ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine. As noted here, that means four of the world’s nuclear powers have been or are engaged in state conflict this year. It is notable that deaths in state-based conflicts have risen markedly over the current decade (see chart).

As well as the toll in lives lost, this trend has at least three important economic and financial implications.

First, the GEP reminds us that armed conflicts result in the destruction of physical and human capital, can lead to sharp increase in poverty and food insecurity and often culminate in deep recessions, reduced private investment and persistent output losses in the countries directly involved. There are also adverse spillover effects. In the affected region, neighbouring countries can suffer from weaker investment due to more uncertainty and more instability. Larger conflicts can also disrupt trade flows, capital flows and commodity prices, trigger volatile asset price movements and displace large numbers of people. Some of these developments can then in turn unleash additional social unrest in the countries impacted, leading to further economic and financial disruption.

According to estimates constructed by economists at the Kiel Institute on the price of war, the economic cost of armed conflict (measured in terms of lost income and reduced physical capital) can see real GDP in directly-affected countries fall by an average of around 30 per cent relative to trend, while inflation rises by around 15 percentage points some five years after the war’s start. Spillover effects for neighbouring countries can see GDP fall by more than 10 per cent, relative to trend and inflation higher by around five percentage points. In contrast, for distant countries, spillovers are typically small and can sometimes even be outweighed by the expansionary effect of higher government (military) spending, while prices tend to remain little changed relative to trend.

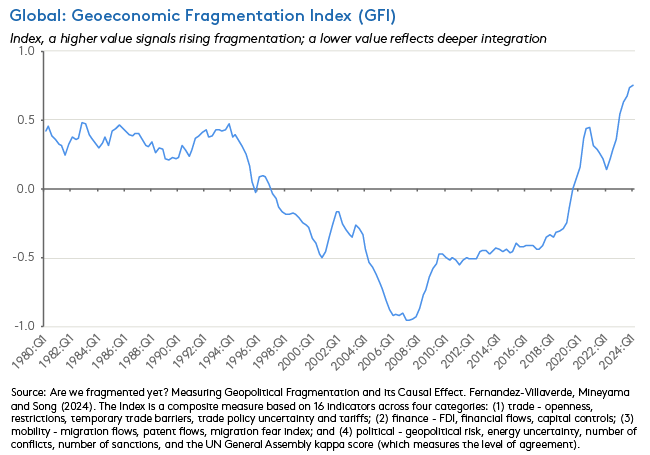

Second, the recent increase in state-on-state conflict is part of a broader rise in geopolitical risk. In its latest Global Financial Stability Report, for example, the IMF reports that one summary measure of geopolitical risk and fragmentation had risen to multi-decade highs by the start of last year (see chart).

The Fund is worried that major geopolitical risks could pose a threat to macro-financial stability. Somewhat reassuringly, an IMF review of around 450 major geopolitical risk events across countries over the 1985-2024 period finds that on average, asset prices react only moderately to most geopolitical risk events (consistent with what we have just witnessed over the past couple of weeks). But the same work does find that major geopolitical events can trigger stock market falls and increases in sovereign risk premia; generate spillovers to other countries through trade and financial linkages, increasing the risk of financial contagion; and can damage the stability and intermediation capacity of bank and non-bank financial institutions.

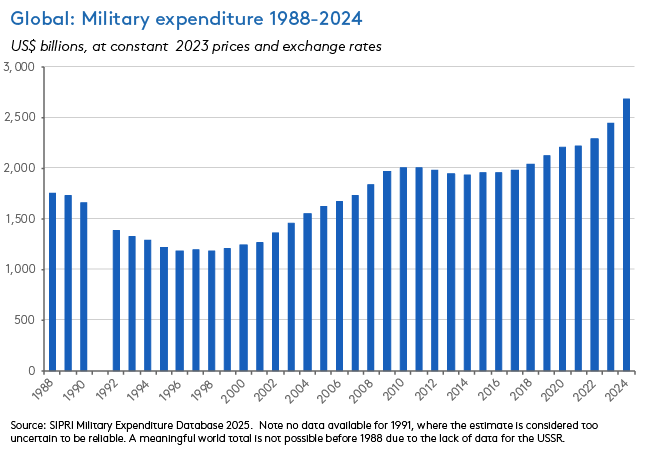

Third, increased conflict and elevated geopolitical risk are manifesting in the highest rate of global defence spending seen since the end of the Cold War. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI)’s Trends in Military Expenditure 2024, world military spending rose to US$2.7 trillion last year. SIPRI reckons spending has now increased every year for a full decade, rising by 37 per cent between 2015 and 2024, while the 9.4 per cent real increase reported last year represented the fastest rate of annual growth seen since at least 1988. World military spending per person is now at its highest level since 1990, while the global military burden – measured as the share of world GDP devoted to military spending – has reached 2.5 per cent in 2024.

Likewise, in its June 2025 Economic Outlook, the OECD acknowledges that – after falling in the three decades following the end of the Cold War - defence spending has now started to increase in many member economies. In Europe in particular, military expenditure has been rising as a share of GDP since Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022. The OECD warns that this boost to outlays will add to budgetary pressures, with the next two years expected to bring a deterioration in budget positions in many of the countries currently planning higher defence spending.

One recent review by the Kiel Institute of 150 years of data based on 113 episodes of military buildups between 1870 and 2020 (excluding the exceptionally large expansions associated with the First and Second World Wars) finds that the average military buildup takes five years and increases military spending by about 1.5 percentage points of GDP (although many booms are larger than that). The same data show that governments typically rely on a mix of deficit financing (borrowing) and higher taxation to fund increases in defence spending, with little reliance on cuts in other government spending (which on average tends to grow, not decline) or on budget reallocation measures. Moreover, the larger the increase in spending, the more dominant the role played by debt, with major conflicts in particular (such as the two World Wars) predominantly debt financed.

It is possible that lifting military spending could have a positive impact on actual or potential economic growth that could in turn help offset some of the associated financing costs. The OECD notes that in the near-term, higher government defence expenditures could lift demand, employment and incomes, especially if financed by borrowing. Such fiscal multipliers are likely to be larger when debt stocks are lower; when monetary policy is accommodative; and when there are already-established local defence industries. It is also possible that increased defence-related Research and Development investment could lift private sector productivity, provided it does not create skills shortages elsewhere in the economy. Alternatively, if increased defence spending instead crowds out capital and labour resources from other, more efficient uses, it could worsen a country’s productivity performance.

What else happened on the Australian data front this week?

Total job vacancies were 339,400 in May 2025, up 2.9 per cent from February 2025 (seasonally adjusted basis). Private sector vacancies rose 3.2 per cent over the quarter, while public sector vacancies were up by a more modest 0.6 per cent. But according to the ABS, relative to the same period last year, the total number of vacancies was down 2.8 per cent and vacancies are now 28.5 per cent lower than their May 2022 peak. On an annual basis, the number of unemployed people for each job vacancy rose from 1.7 to 1.8, which is still well below the pre-pandemic (February 2020) level of 3.1.

Australian household wealth rose by 0.8 per cent or $137.1 billion to reach $17.3 trillion in the March quarter 2025. The ABS said this rise largely reflected a 1.2 per cent or $125.3 billion increase in the value of residential land and dwellings.

The ABS said the value of Engineering Construction work done fell 1.7 per cent over the March quarter 2025 (volume terms, seasonally adjusted) but was still up 3.3 per cent over the year. Private sector work done rose 0.3 per cent quarter-on-quarter and was up two per cent year-on-year, while public sector work done fell 3.8 per cent quarter-on-quarter while rising 4.8 per cent in annual terms.

The ANZ-Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence Index was up 1.3 points to 86.7 points in the week ending 22 June 2025. There were increases for four of the five subindices, led by a 4.4-point jump in ‘time to buy a major household item’, which is now at its highest level since April 2022 and a 2.6-point rise for ‘future financial conditions.’ In the case of the former, ANZ pointed to ongoing end-of-financial-year sales. At the same time, however, the ‘short-term economic confidence’ subindex fell 1.1 points, perhaps reflecting the adverse impact of international uncertainty.

Other things to note . . .

- Andrew Leigh, Assistant Minister for Productivity, Competition, Charities and Treasury spoke on The progressive productivity agenda, making the case for investing in skills, health and opportunities, in infrastructure (including housing and digital), and in institutions (including competition reform and reducing the cumulative burden of regulation).

- Related, a new e61 Institute report asks, will young Australians be better off than past generations?

- The AFR’s John Kehoe looks at lessons for tax reform after 25 years of GST and discusses the case for a dual income tax.

- Saul Eslake on prospects for a ‘fairer’ state carve-up of the GST.

- The Productivity Commission’s June 2025 Quarterly Productivity Bulletin notes that Australia’s productivity woes continued into the first quarter of this year and includes a discussion on productivity and the choice between work and leisure. Here, the record shows Australians have opted to ‘spend’ most of our productivity dividend (about 77 per cent) on more income and more and better stuff, rather than by taking more leisure (23 per cent).

- The ABS examines the nuts and bolts of the Australian construction industry, which as of 2023-24 accounted for seven per cent of GDP and employed around 1.3 million people.

- Hugh White’s Quarterly Essay, Hard New World. White reckons Australia has so far failed to fully engage with the consequences of the shift to a multipolar world characterised by regional great powers, including an increasingly multipolar Asia. In White’s words: ‘The world America made for us is passing away. Its place is being taken by a new and harder post-American world…Our leaders are still in denial about all this. They hope that the old rules-based order will somehow revive and survive, so that things will go back to the way they were in John Howard’s day.’

- The Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO)’s 2025 Election Commitments Report estimates that – relative to numbers presented in the 2025 Pre-election Economic and Fiscal Outlook (PEFO), the election commitments made by Labor would result in a slightly smaller underlying cash deficit by the end of the 2025‑26 Budget forward estimates, the Coalition’s platform would result in a smaller underlying cash deficit and the Greens’ platform would result in a larger underlying cash deficit. By the end of the medium term, Labor's platform would result in an improvement in the underlying cash balance in line with the PEFO baseline, while the Coalition and Greens' platforms would decrease it.

- A new report on Australia’s Artificial Intelligence ecosystem, from the National Artificial Intelligence Centre.

- Three new BIS Bulletins, one explaining the April-May 2025 slide in the US dollar (currency hedging by Asian investors seems to have been important) and one analysing Household inflation expectations after the post-pandemic inflation breakout (survey evidence suggests inflation expectations remain elevated despite inflation rates heading back towards target, pointing to the lasting impact of temporary inflation bursts). A third examines investment in an increasingly uncertain global economy (private business investment could suffer from current high uncertainty levels, while in the long run the investment outlook looks likely to be shaped by tariff-led supply chain shifts, public investment, and structural reform).

- Barry Eichengreen considers the future of the global monetary system.

- Bruegel examines 10 challenges facing China’s economy. These include very limited fiscal space; Constrained monetary policy; Subdued domestic demand; Geopolitical risks to external demand; Overcapacity and deflationary pressures; Stubbornly low private consumption; Ongoing real estate-led asset price deflation; Over-investment leading to increasingly low returns; A shrinking population and US technological containment.

- Related, Is China really growing at five per cent?

- On AI model collapse.

- The Economist magazine says Western countries have successfully cut migration numbers and must now face the economic consequences.

- The WSJ analyses the relentless political pressure on the US Fed at a time when Fed policymakers themselves are divided over the future path of monetary policy. The piece argues that while presidential pressure on the Fed is hardly new, the Trump administration’s approach is unusually public.

- Paul Kedrosky on Life under two (that is, under two per cent annual economic growth). Kedrosky’s argument is that a shift in US average annual growth from more than three per cent to less than two per cent explains rising populism, fiscal strain, antipathy towards immigration and distrust in institutions. But there is also the chance that a new growth wave based on robotics and AI could change the prognosis.

- A new e-book from CEPR offers a preliminary assessment of the economic consequences of the Second Trump Administration.

- At the cross-roads of stagflation: Apollo’s mid-year economic outlook.

- New OECD research on regulation and growth, drawing on lessons of nearly half a century of product market reform. Authors focus on the impact of anticompetitive regulations in upstream sectors (particularly barriers to entry) that impact long-run economic performance in downstream sectors. They reckon rapid deregulation of network sectors (energy, telecoms, and transport) contributed around 0.25 percentage points to annual labour productivity growth during the 1995-2005 boom and that its subsequent slowdown could account for up to one-sixth of the post-2005 productivity slowdown.

- Also from the OECD, Government at a Glance 2025. According to the accompanying Australia country note, 46 per cent of Australians had high or moderately high trust in the national government in 2023, compared to an OECD average of 39 per cent. OECD Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance (iREG) measure the quality of Regulatory impact assessments (RIA) systems for primary laws in OECD countries across four dimensions - oversight and quality control, transparency, systematic adoption and methodology. In the 2024 survey, Australia scored 2.8 on the index (on a 0-4 scale), above the OECD average of 2.3.

- An interesting Conversations with Tyler discussion with Chicago Fed president Austan Goolsbee.

- Recommended by a reader, the Capitalisn’t podcast asks Cliff Asness if financial markets are getting dumber and discusses his ‘less-efficient market hypothesis’.

- Another in the Politics on Trial series from the Past, Present, Future podcast: Galileo vs the Inquisition.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content