Australia, like many of its advanced economy peers, has a growth problem. Last week’s national accounts numbers not only depict an economy that got off to a soft start this year, but also one where per capita growth has been depressingly hard to come by in the aftermath of the pandemic. Based on a simple average, Australia’s annual growth in real GDP per capita had already halved, falling from a bit over two per cent in the pre-GFC ‘Golden Age’ (between 2000 and 2007) to around one per cent in the post-GFC, pre-pandemic era (2010-2019). Between 2022 and the first quarter of this year, per capita growth has halved again, averaging a bit less than 0.5 per cent.

To be sure, some of this latest slowdown is cyclical, reflecting the lingering impact of COVID-19 disruptions and higher interest rates that the RBA later deployed to tame the post-pandemic inflation shock. But it also indicates an ongoing challenge around productivity growth. The latter also slowed after the GFC and has yet to sustainably recover. Indeed, in recent years, productivity has gone backwards, although here too it is hard to disentangle the impact of pandemic-driven fluctuations (the ‘productivity bubble’) from underlying trends.

Sluggish growth and lacklustre productivity are never welcome news for policymakers. But the deteriorating global environment (see the story below on yet another global growth downgrade) is making them particularly exercised about the adverse consequences for economic resilience. As I wrote here, Australia’s new government is mindful of the challenge. The day after May’s crushing election win, the Treasurer declared, ‘The best way to think about the difference between our first term and the second term … [is that while the] … first term was primarily inflation without forgetting productivity, the second term will be primarily productivity without forgetting inflation.’ That message followed the government’s previous tasking of the Productivity Commission with ongoing inquiries into the Five Pillars of Productivity (outlined here), with draft reports due this July and August.

We know from the AICD’s own Director Sentiment Index (DSI) that directors too are increasingly concerned by Australia’s productivity woes. According to our latest survey, directors rank productivity growth second only to global economic uncertainty as among the top economic challenges currently facing economic business. And directors rank productivity growth as the most important issue for the Federal government to address in both the short term and the long term.

Given this context, it was encouraging that this week delivered another push on the productivity front. In his address to the National Press Club this week, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese declared Australia must ‘move quickly to build an economy that is more dynamic, more productive and more resilient’. He has asked his Treasurer to ‘convene a roundtable to support and shape our government’s growth and productivity agenda. At Parliament House in August, we will bring together a group of leaders from the business community, the union movement and civil society… We want to build the broadest possible base of support for further economic reform. To drive growth. Boost productivity. Strengthen the budget. And secure the resilience of our economy, in a time of global uncertainty’. One to watch.

In the rest of this week’s note, we review recent views on the international economic outlook and consider the latest signals on consumer sentiment. There is also our regular roundup of other data releases and of interesting links.

Finally, one last reminder that next Tuesday I’ll be speaking at the AICD’s National Economic Update in Melbourne.

Another week, another downgrade to a global growth forecast

This week it was the turn of the World Bank to downgrade its expectations for world GDP growth. According to the June 2025 Global Economic Prospects (GEP), ‘global growth is slowing due to a substantial rise in trade barriers and the pervasive effects of an uncertain global policy environment’. The Bank now thinks the world economy will grow at just 2.3 per cent this year, marking the weakest result since 2008 (excluding outright global recessions). That represents a 0.4 percentage point downgrade to the Bank’s January 2025 projections. The growth forecast for advanced economies has been trimmed even more, with a 0.5 percentage point cut taking expected growth this year down to 1.2 per cent. The Bank has also cut its 2026 forecasts for world growth (down 0.3 percentage points to 2.4 per cent) and advanced economy growth (down 0.4 percentage points to 1.4 per cent).

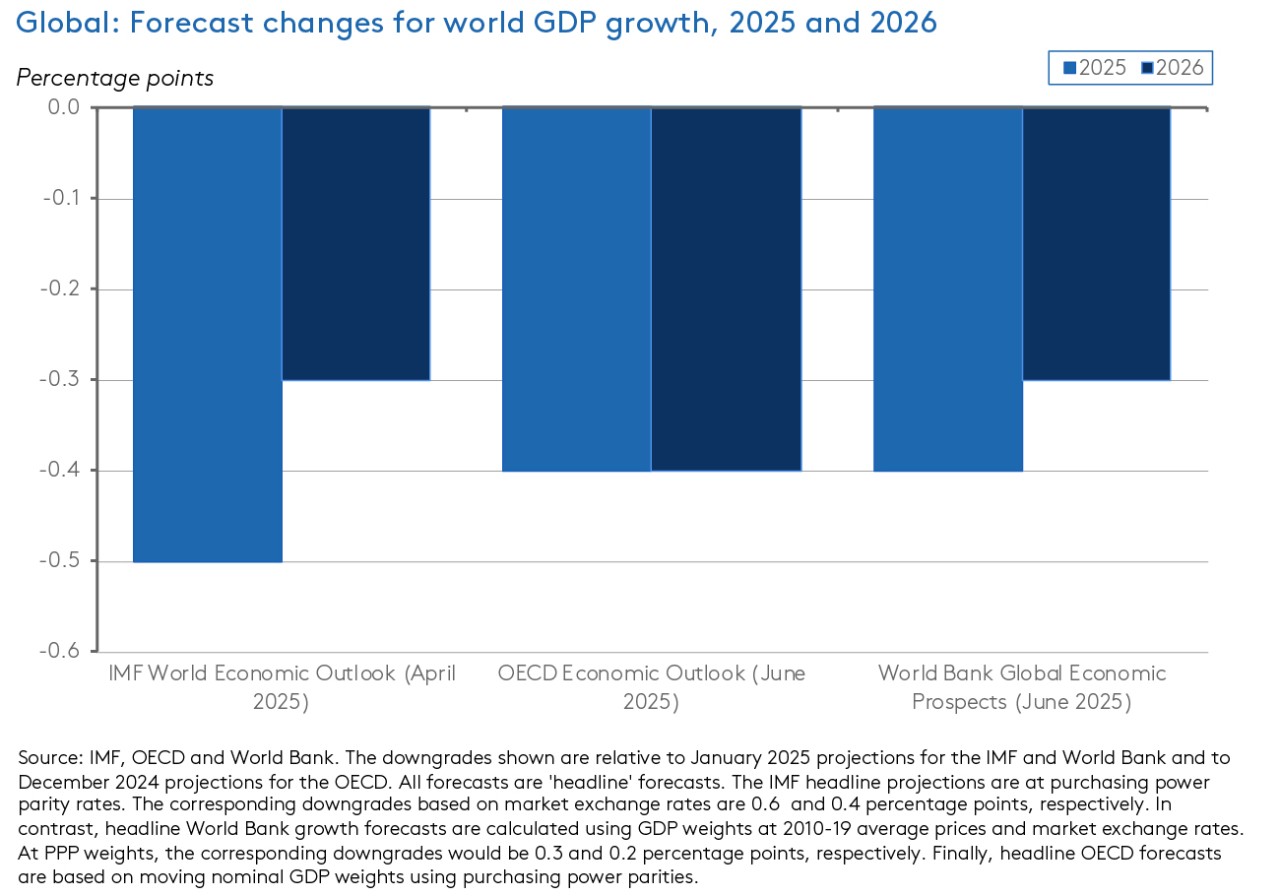

The GEP downgrades follow similar cuts to growth forecasts by the IMF and the OECD earlier this year (see chart above). Differences between the projections partly reflect differences in methodology (for example, weighting global GDP by market exchange rates vs using purchasing power parity exchange rates), as well as in timing.

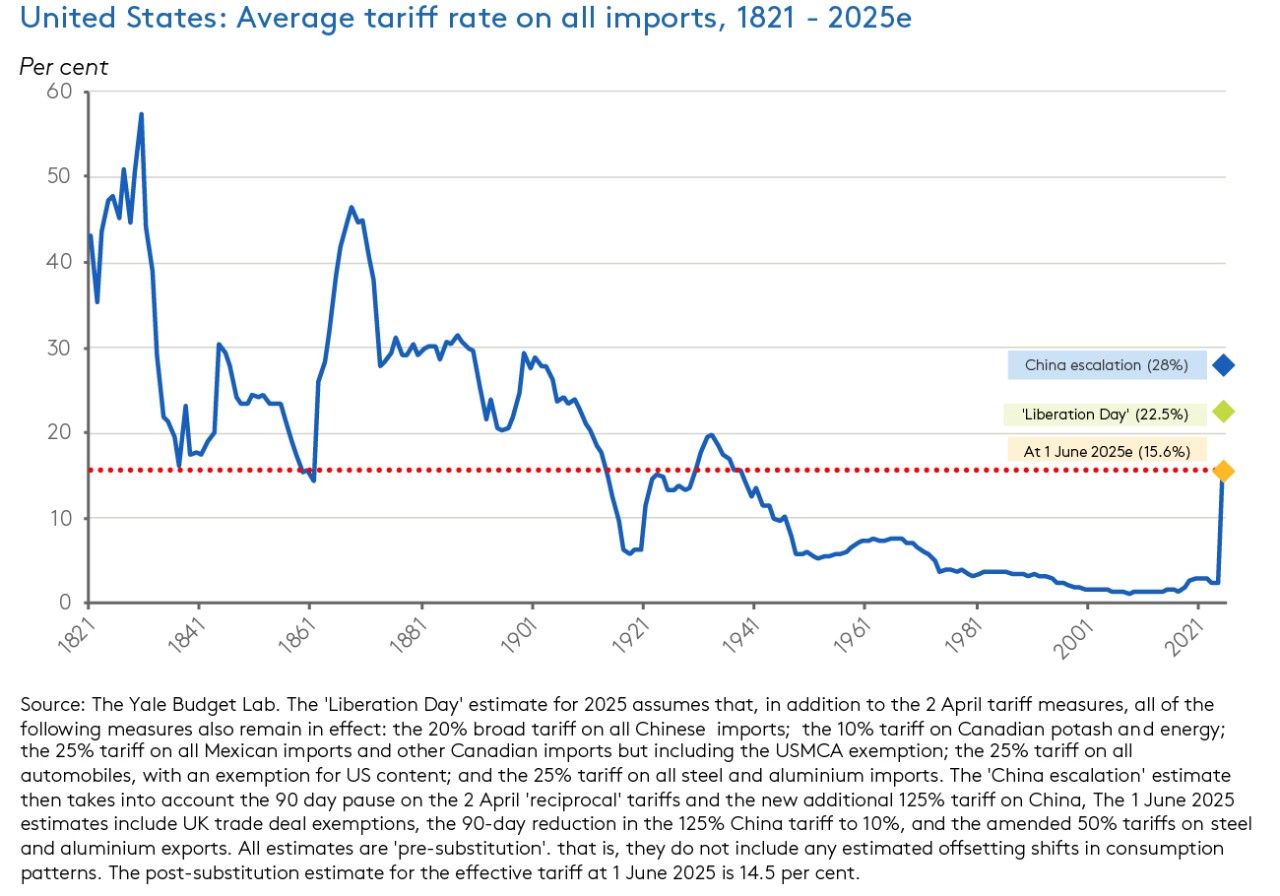

The GEP projections assume that tariff rates in line with those that applied in late May 2025 will prevail across the forecast horizon (that is, the GEP assumes that all existing pauses at that time will persist). In contrast, the earlier IMF projections assume tariff rates based on measures announced as of 4 April this year (which includes the 2 April ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs plus Beijing’s retaliatory measures). While levels of protection remain high in all scenarios relative to the world in 2024, the volatility in trade policy announcements, including the introduction of various pauses and postponements, means the estimated US effective tariff rate has changed quite significantly month-to-month (see chart below).

Australian households remain cautious about the outlook

We know from our review of the RBA’s May 2025 forecasts in the latest Statement on Monetary Policy (SMP) that one key uncertainty for Australia’s economic outlook relates to the future trajectory of house consumption. May’s SMP acknowledged that the recovery in household consumption in the first quarter of this year was running weaker than the RBA had anticipated at the time of the February 2025 SMP, prompting the central bank to revise down its expectations for near-term consumption growth, while continuing to project a return to pre-pandemic rates of growth over coming years. The weakness in per capita consumer spending in the March quarter national accounts reinforced that message.

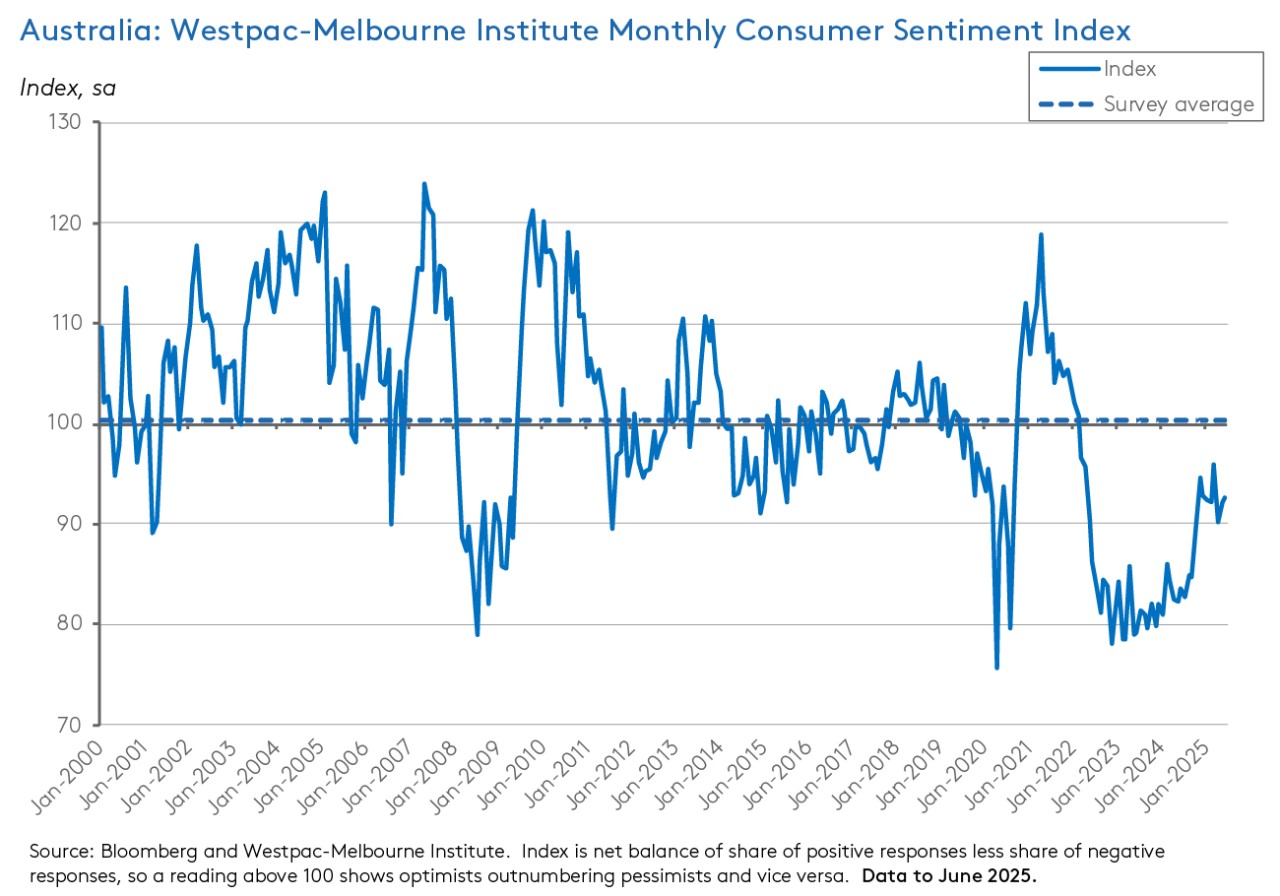

It follows that it is useful to keep an eye on what survey measures of consumer confidence are indicating about households’ appetite for future spending. Take the latest Westpac-Melbourne Institute Consumer Sentiment Index reading, which rose 0.5 per cent to 92.6 in June 2025, up from 92.1 in May. Westpac said the detail of the survey showed ‘two clear opposing forces at work’. On the one hand, last month’s RBA rate cut, plus easing inflationary pressures are lifting sentiment, particularly in the case of buyer attitudes towards major purchases. On the other hand, negative news on international conditions and sluggish domestic growth readings are both weighing on household confidence. These contrasting forces are visible in the different results by subindex. For example, the ‘time to buy a major household item’ subindex jumped by 7.5 per cent over the month to a reading of 100.2. That marked the first positive result since March 2022 (recall, optimists outnumber pessimists at readings above the neutral level of 100). The remaining increase for June came in the ‘family finances vs a year ago’ subindex, which edged higher by 0.5 per cent while remaining weak in levels terms at just 75.4. At the same time, the other three subindices all fell over the month: ‘family finances next 12 months’ (down 1.9 per cent to 98.8), ‘economic conditions next 12 months’ (down 0.7 per cent to 92.4) and ‘economic conditions next five years’ (down 2.4 per cent to 96.2).

Other survey results reported this month included a five per cent rise in the Westpac-Melbourne Institute Unemployment Expectations Index (indicating that more consumers now expect unemployment to increase over the year ahead. However, in level terms the index is still slightly better than its long run average) and a 6.8 per cent fall in the Westpac-Melbourne Institute Interest Rate Expectations Index (down to a 13-year low, signalling that more respondents expect further rate cuts from here). There were also monthly increases for the Time to buy a dwelling index (which hit its highest level since September 2021) and the House price Expectations Index (now at its highest level since 2013).

Meanwhile, the weekly ANZ-Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence Index was little changed at 86.7 for the week ending 8 June 2025, up just 0.3 points on the previous week. Across the subindices, increases in ‘current financial conditions’ and ‘medium-term economic confidence’ were offset by falls in ‘future financial conditions’ and ‘short-term economic confidence’. The most notable change was a 3.2-point jump in the ‘time to buy a major household item’ subindex, which ANZ said had reached its highest level since April 2022, likely reflecting the start of end of financial year sales.

What else happened on the Australian data front this week?

According to the NAB Monthly Business Survey for May 2025, ‘business conditions remained weak amid ongoing profitability pressures and soft demand, with signs of a further softening in labour demand’. The survey’s business conditions index fell from +2 index points in April to 0 last month, after having previously dropped from +3 in March. By subindex, employment fell from a reading of +4 in April to 0 in May (a new cyclical low) while trading was down from +6 to +5 and profitability was unchanged at -4. In contrast, business confidence continued to improve. After having increased from -2 in March to -1 in April, the confidence index rose again to +2 in May. Capacity utilisation was also up from a weak reading of 81.4 per cent in April to 82.3 per cent last month, a little above the series’ long-term average. NAB noted that retail conditions and retail confidence have both fallen over the year to date, unwinding the modest recovery seen towards the end of last year, which is consistent with the soft start to consumer spending in 2025 discussed above. Finally, the survey reported mixed results in terms of prices and cost pressures. Purchase cost growth slowed from 1.7 per cent in April (quarterly equivalent terms) to 1.1 per cent in May, while labour cost growth rose from 1.5 per cent to 1.7 per cent over the same period. Growth in final product prices slowed from 0.8 per cent to 0.5 per cent, while the rate of increase in retail prices was unchanged at 1.2 per cent.

The ABS said there were 44 industrial disputes in the March quarter 2025, down from 69 disputes in the December quarter 2024. There were also declines in the number of employees involved (10,300, down from 25,200) and working days lost (13,900 down from 53,800). Over the year to the March quarter 2025, there were a total of 189 disputes, compared to 207 disputes in the year ended March quarter 2024. However, the number of employees involved was up (85,400 vs 52,900) as was working days lost (136,200 vs 108,300).

The total value of residential dwellings in Australia rose by $130.7 billion to $11.4 trillion in the March quarter of this year. The ABS said the number of residential dwellings increased by 53,400 to just below 11.4 million over the same period. As a result, the national mean price of residential dwellings rose by $6,900 to exceed $1 million for the first time, hitting $1,002,500.

The ABS Monthly Business Turnover Indicator reported a monthly increase of 0.3 per cent (seasonally adjusted) in the 13-industry aggregate for April 2025. Seven of the 13 industries reported higher turnover across the month, led by Accommodation and food services (up 3.8 per cent) and Arts and recreation services (up 3.7 per cent), with the Bureau highlighting a lift from the ’10-day super-break’ across the Easter and ANZAC day weekends. On an annual basis, business turnover rose 3.3 per cent and was up in 11 of the 13 industries, led by Manufacturing (up 11.4 per cent) and Accommodation and food services (up 10.6 per cent).

Last Friday, the ABS published the Labour Account for the March quarter 2025. According to the Bureau, the total number of jobs fell by 0.2 per cent over the quarter (seasonally adjusted) to 16.3 million, which was up two per cent over the year. The number of filled jobs edged down by 0.1 per cent over the quarter to 15.9 million, a result which was 2.3 per cent higher than in the same quarter of last year. The ABS said this was the first quarterly drop reported in filled jobs since the September quarter 2021, which was marked by the COVID-19 Delta lockdowns. It likewise marked the first quarterly fall in private sector filled jobs (down 0.2 per cent) since the September quarter 2021 and the first decline in public sector jobs (down 0.1 per cent) since the June quarter 2022. Hours worked last quarter were up 0.3 per cent over the previous quarter at six billion hours. Finally, the vacancy rate fell to two per cent, which is the lowest rate since the March quarter 2021 and well down from its peak of 3.2 per cent in the September quarter 2022. Even so, it remains higher than the pre-pandemic rate of around 1.6 per cent.

Other things to note . . .

- The ABS presents nine facts about the Australian economy from the March quarter 2025. Notable developments included the biggest fall in public spending since the September quarter 2017, the lowest underlying inflation rate since the December quarter 2021 and the lowest level of GDP per person since the September quarter 2021.

- Also from the ABS, insights into the Australian labour market over the past five years. The Bureau says that over the past half-decade, and after early disruption from the COVID-19 pandemic, the labour market has been characterised by strong employment growth, record low levels of unemployment, and record highs in both the participation rate and the job vacancy rate.

- In the AFR, John Kehoe suggests six tax changes Canberra should implement.

- On the shrinking ASX.

- Grattan says the government needs a gas policy.

- The 2025 Productivity Commission Report on Government Services.

- The Lowy Institute’s Richard McGregor on the World According to Xi Jinping.

- A new BIS Bulletin considers regional integration amid global fragmentation.

- This FT Big Read asks, can Japan hold on to its ‘indispensable companies’?

- Another FT Big Read, the mounting pressure on bond markets.

- Related, will a world of more supply shocks reduce the convenience yield premium on sovereign bonds, requiring greater fiscal prudence?

- Also related, what might a world with no safe assets look like? More capital controls, more reliance on domestic sources of financing and the rise of ‘digital currency areas’ are possibilities.

- And the WSJ looks at the mechanics of US government borrowing.

- The IMF examines New Zealand’s productivity challenge.

- The Economist magazine’s list of the 40 best books published so far this year.

- A Techno-industrial policy playbook for the United States.

- Introducing the OECD’s AI Capability Indicators.

- On the Collapse of the Knowledge System.

- Wired says You’re not ready… for AI scammers and AI hacker agents, a grid attack, quantum computer decryption, phone dead zones and GP blackouts.

- The FT’s Economics Show is hosting a six-part conversation between Martin Wolf and Paul Krugman. The first two episodes cover the trust crisis and how the old economic order fell out of favour. Probably more political economy than economics so far, but that is a sign of the times.

- Econtalk with Noah Smith on libertarianism and ‘econ 101.’

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content