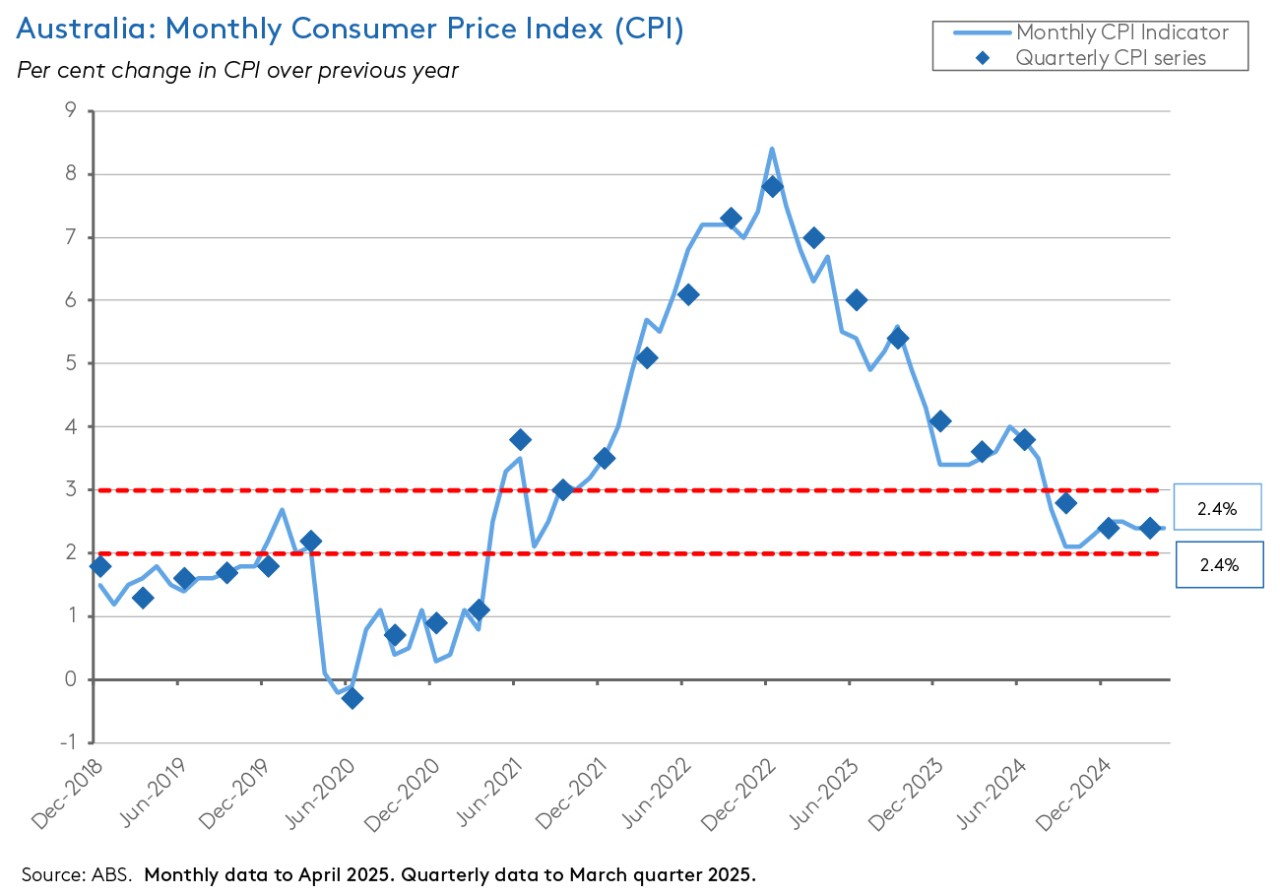

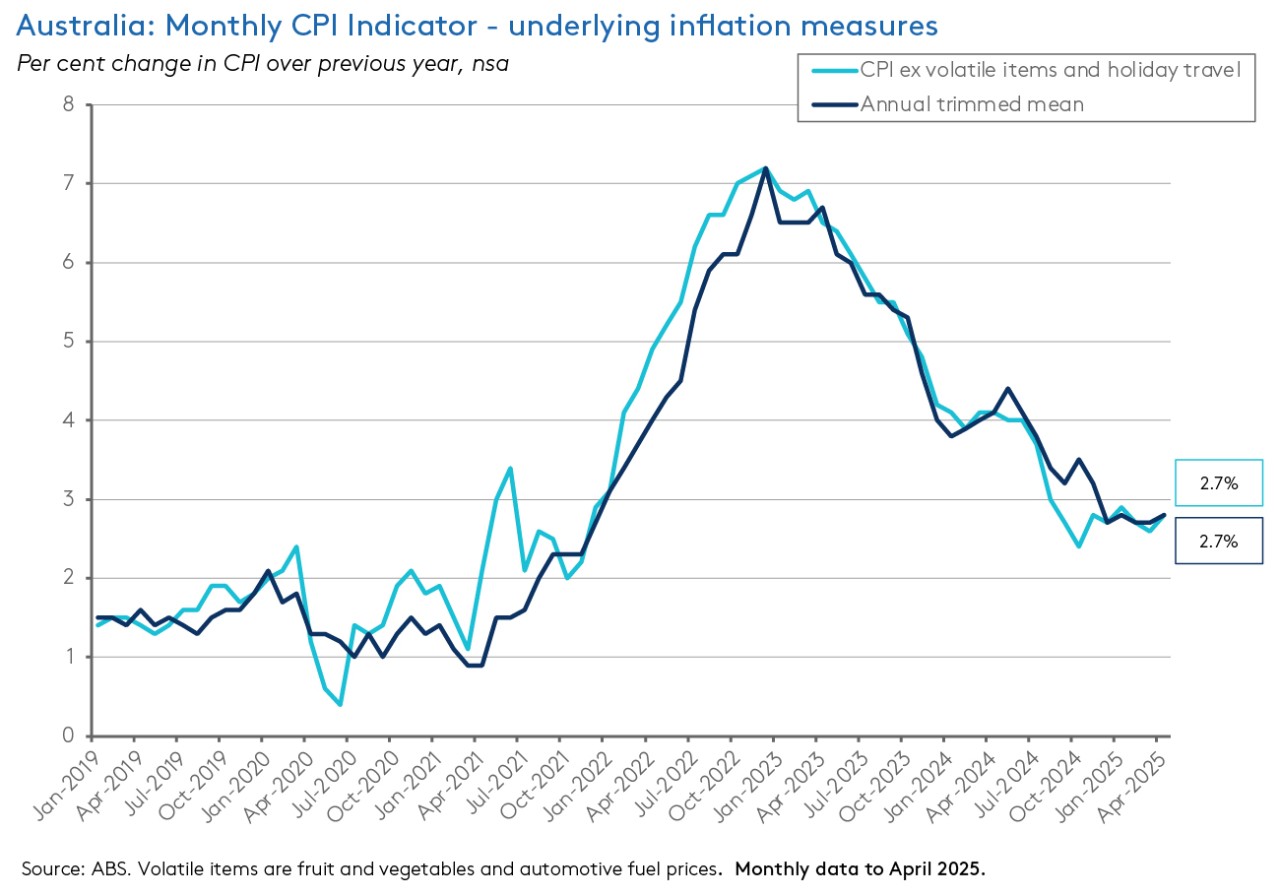

This week’s monthly inflation reading showed the annual rate of increase in Australia’s Monthly Consumer Price Index (CPI) indicator unchanged in April 2025, running at 2.4 per cent for a third consecutive quarter. At the same time, underlying inflation ticked up to 2.8 per cent, which again was little changed from previous months’ readings.

Keeping in mind that the RBA is more focussed on the quarterly data than the monthly readings, there was nothing in this result to make the case for ‘going early’ with a rate cut at the 8 July meeting versus waiting to cut again until 12 August. In the absence of a compelling story in the domestic data flow, much will continue to depend on the external environment where it is at least possible that this week’s ruling by the US Court of International Trade that the Trump 2.0 global tariffs are illegal could positively influence the external environment…but alternatively it could just add further to the sense of uncertainty around the conduct of US trade policy.

We dig into the monthly inflation numbers in more detail below. We also review the RBA’s progress with delivering disinflation to date and consider whether its ‘mission accomplished’ time for Martin Place. And this week’s linkage roundup includes short summaries of the Treasury Secretary’s assessment of economic conditions and the Productivity Commission’s analysis of Australia’s productivity performance before and after the pandemic.

Finally, a reminder that the AICD’s National Economic Update is coming up on 17 June.

Monthly CPI indicator inflation was steady in April 2025

The ABS said that the Monthly Consumer Price Index (CPI) Indicator rose by 2.4 per cent over the year in April 2025. That marked a third consecutive month of a stable annual rate of increase and a ninth consecutive month of sub-three per cent inflation. On the other hand, the outcome was slightly stronger than the market consensus forecast, which had anticipated a modest slowdown in the rate of inflation to 2.3 per cent.

The accompanying measures of annual underlying inflation both edged slightly higher in April while also remaining below three per cent. The Annual trimmed mean rate increased from 2.7 per cent to 2.8 per cent while the CPI excluding volatile items and holiday travel rose from 2.6 per cent to 2.8 per cent. The former has now fluctuated between 2.7 and 2.8 per cent for the past five months while the latter has been below three per cent for eight consecutive readings.

According to the Bureau, the largest contributors to the annual growth in the headline CPI Indicator were Food and non-alcoholic beverages (up 3.1 per cent in April compared to 3.4 per cent in March this year), Housing (up 2.2 per cent from 1.8 per cent) and Recreation and culture (up 3.6 per cent from 2.7 per cent):

- Within the Food and non-alcoholic beverages group, higher cocoa prices contributed to increased prices for snacks and confectionary (up 5.4 per cent) while egg shortages due to bird flu pushed up the price of eggs (up 18.6 per cent).

- Within the Housing group, New dwelling prices rose 1.2 per cent over the year to April, up from one per cent growth in March (although the ABS noted that the April result was still the second weakest annual increase since April 2021). Notably, new dwelling prices rose 0.5 per cent over the month, recording their first increase since December last year. Rents were up five per cent over the year. That compared to a 5.2 per cent increase in March and marked the softest annual growth in rental prices since February 2023, which the ABS said was consistent with higher vacancy rates and slower growth in advertised rents across most capital cities. And electricity prices fell 6.5 per cent over the year following a 9.6 per cent fall in the previous month. The smaller drop mainly reflected most Queensland households having used up their state government rebate and all Western Australia households having used up both their second instalment of the Commonwealth Energy Bill Relief Fund and their state government rebate.

- The rise in the rate of price increases for the Recreation and Culture group was driven by a rise in price growth for Holiday travel and accommodation, which was up from 3.9 per cent over the year in March to 5.3 per cent in April. The Bureau highlighted the contribution of international travel and accommodation, noting that prices for international airfares and accommodation rose across many popular destinations during the Easter and school holiday period.

There were also increases for the Furnishings, household equipment and services (from 0.6 per cent to one per cent), Health (from four per cent to 4.4 per cent due to increases in health insurance premiums which rose on 1 April and contributed to the largest April monthly rise in medical and hospital services since 2018), Communications (up from 0.2 per cent to 0.7 per cent) and Insurance and financial services (from 3.9 per cent to four per cent) groups.

Moving in the opposite direction, disinflation in the Transport group increased in April, with the annual rate of price decline hitting 3.2 per cent after prices had fallen by 1.9 per cent over the year in March. That in turn was the product of a 12 per cent year-on-year fall in automotive fuel prices, following a 7.6 per cent fall in March.

Finally, by broad analytical category, goods inflation eased from 1.1 per cent in March to just 0.9 per cent in April while services inflation accelerated from 3.9 per cent to 4.1 per cent (although note the limited coverage of services in the first month of the quarter). Likewise, while the rate of tradables inflation slowed from 0.9 per cent to 0.3 per cent between March and April of this year, the rate of non-tradables inflation picked up from 3.2 per cent to 3.6 per cent.

Off the Narrow Path and on to ‘Mission accomplished’ for the RBA?

Although the outcome was slightly higher than expected, April’s monthly inflation numbers were nevertheless another in a sequence of data points confirming that headline and underlying inflation are both back within the RBA’s target band. Granted, the RBA itself is sceptical about the merits of the Monthly CPI Indicator. It prefers to focus on the quarterly CPI. But there too progress on disinflation has been significant.

So, mission accomplished? In her press conference last week, Governor Bullock – cautiously – referred to the RBA’s successful policy campaign, which has lowered inflation at minimal cost to employment, by declaring:

‘I think I’m going to retire the narrow path analogy now. I don’t want to sort of suggest that I’m 100 per cent confident that we’re there, but it is really encouraging that we do manage - we have got inflation down, and we still have employment holding up, but this is not a situation that is going to just be the equilibrium, I think. We’re always going to be thrown off course by things, as we’ve seen.’

How should we gauge the success of Australia’s central bank here? Recall that while the overarching goal of monetary policy for the RBA is the ‘economic prosperity and welfare of the Australian people’ this is framed in terms of a dual mandate that requires Martin Place to conduct ‘monetary policy in a way that will best contribute to both price stability and full employment.’

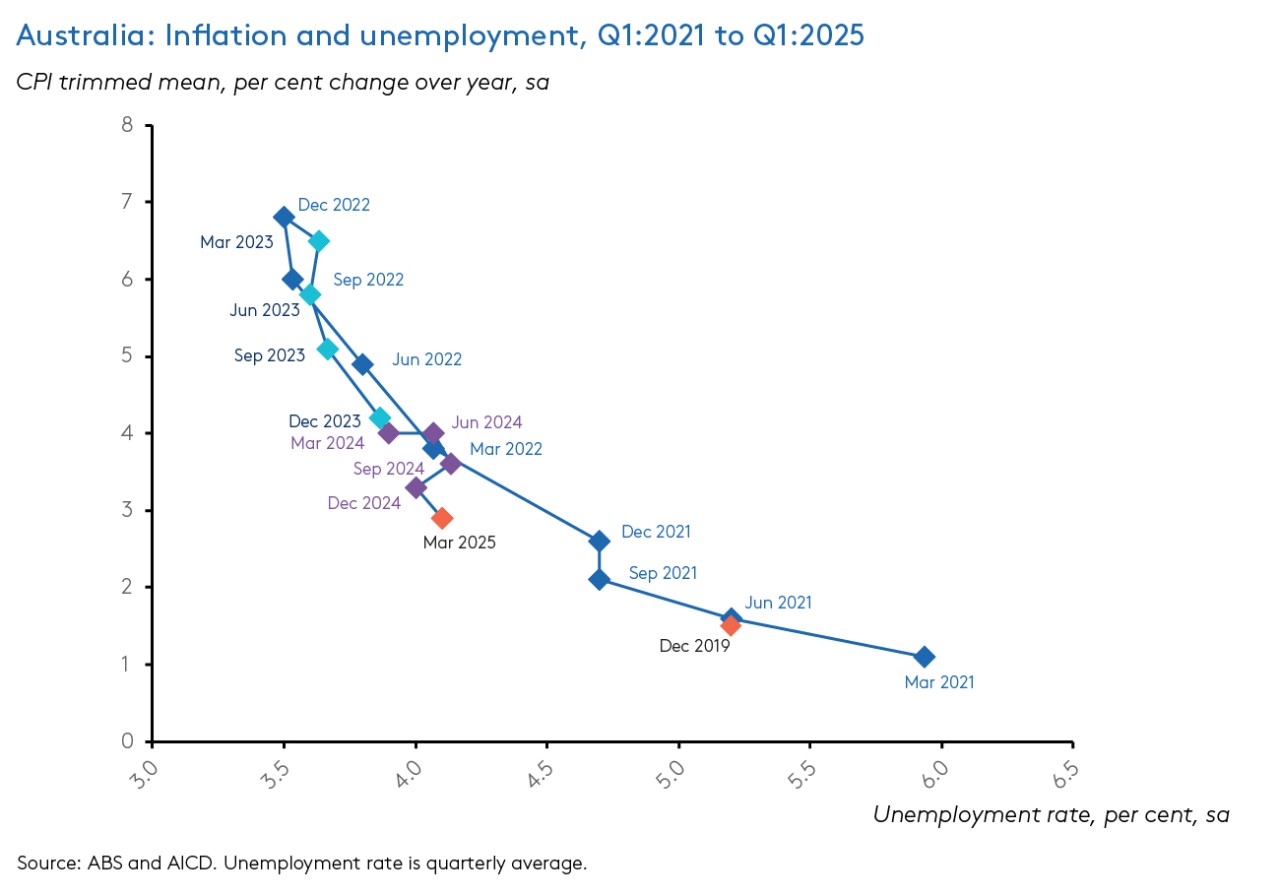

In that context, let’s start by considering shifts in the relationship between inflation and unemployment (sometimes known as the Phillips Curve). Back in the final quarter of 2019, before the onset of the pandemic, Australia’s underlying inflation rate was below the bottom of the target band at 1.5 per cent, while the unemployment rate stood at 5.2 per cent. By March 2021, after a year of COVID-19, the underlying inflation rate had fallen further below target to just 1.1 per cent while the unemployment rate had climbed to almost six per cent. Thereafter, as the economy recovered, the unemployment rate fell while the inflation rate rose sharply, with the latter spurred on by a mix of policy stimulus and external shocks, particularly the war in Ukraine. Underlying inflation went on to peak at 6.8 per cent in the December quarter 2022 by which point the unemployment rate had fallen to 3.5 per cent.

Since then, the RBA has overseen a sustained and relatively steep decline in the inflation rate accompanied by only a modest rise in the unemployment rate (see chart).

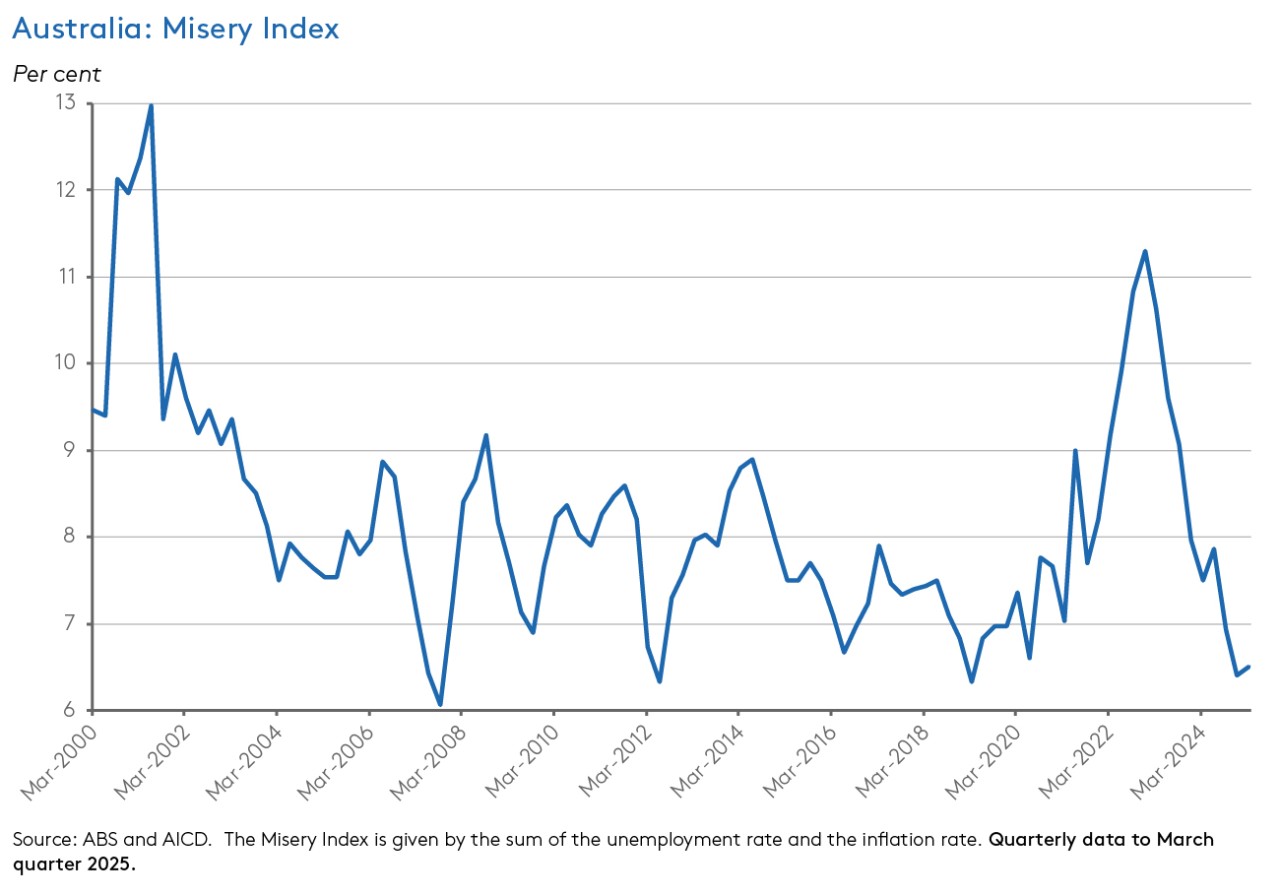

We can also take a related perspective by looking at this in terms of a simple misery index which adds together the inflation and unemployment rate. On the eve of the pandemic, in the December quarter 2024 this index stood at around seven per cent using the headline inflation rate or a little below that using the underlying inflation rate (noting that the index does not ‘punish’ below-target inflation). It then peaked at more than 11 per cent (headline inflation) or more than ten per cent (underlying inflation) in the December quarter 2023. Since then, it has fallen back to roughly where it was pre-pandemic, albeit with a shift in composition reflecting the fact that inflation is a higher and back within the target band while unemployment is lower (see chart).

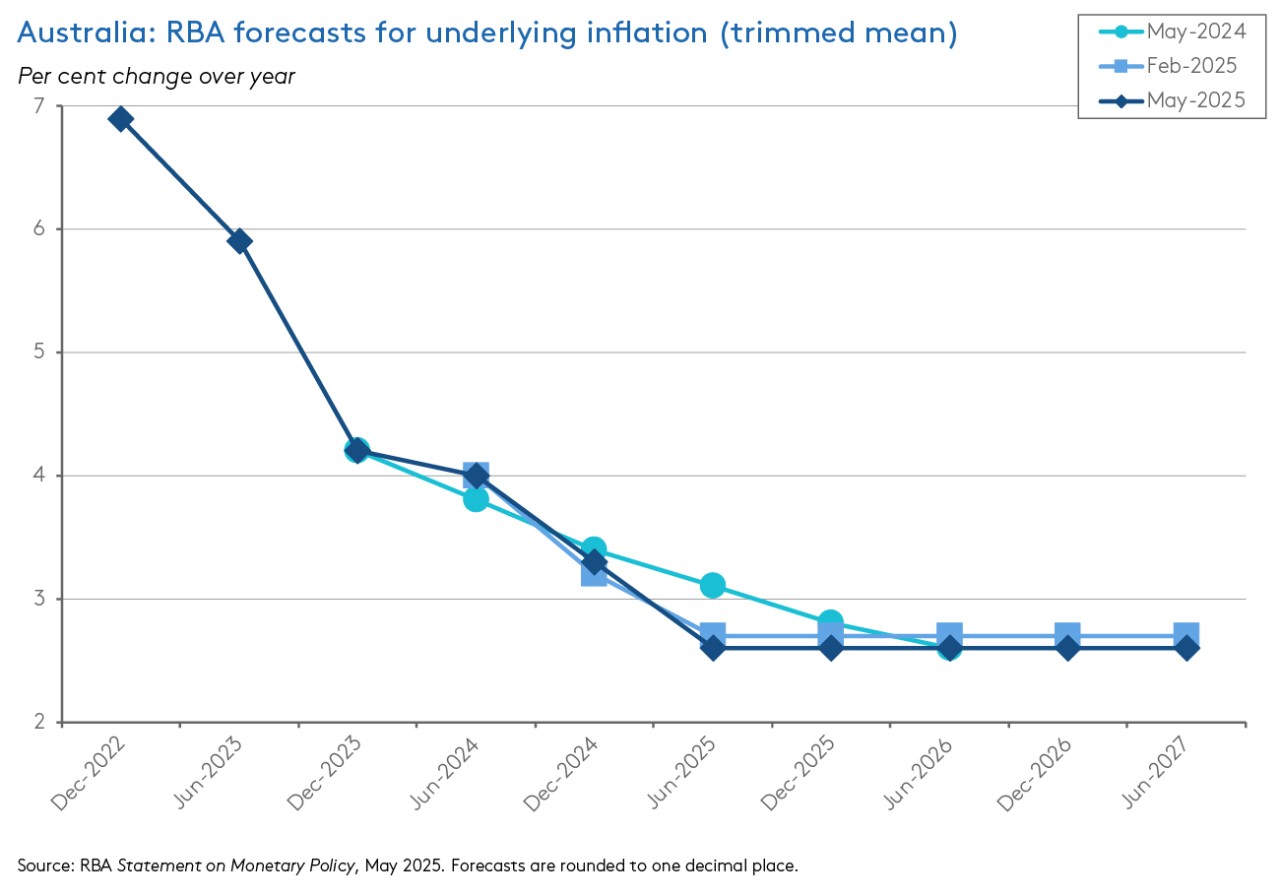

A second approach is to be more forward-looking and consider what the RBA now thinks will happen with inflation and interest rates over the coming years. According to the central scenario presented in the May 2025 Statement on Monetary Policy (SMP), the central bank now projects underlying inflation to remain around the middle of the target band for inflation through to mid-2027 (which is also a bit lower than it anticipated in the February 2025 SMP):

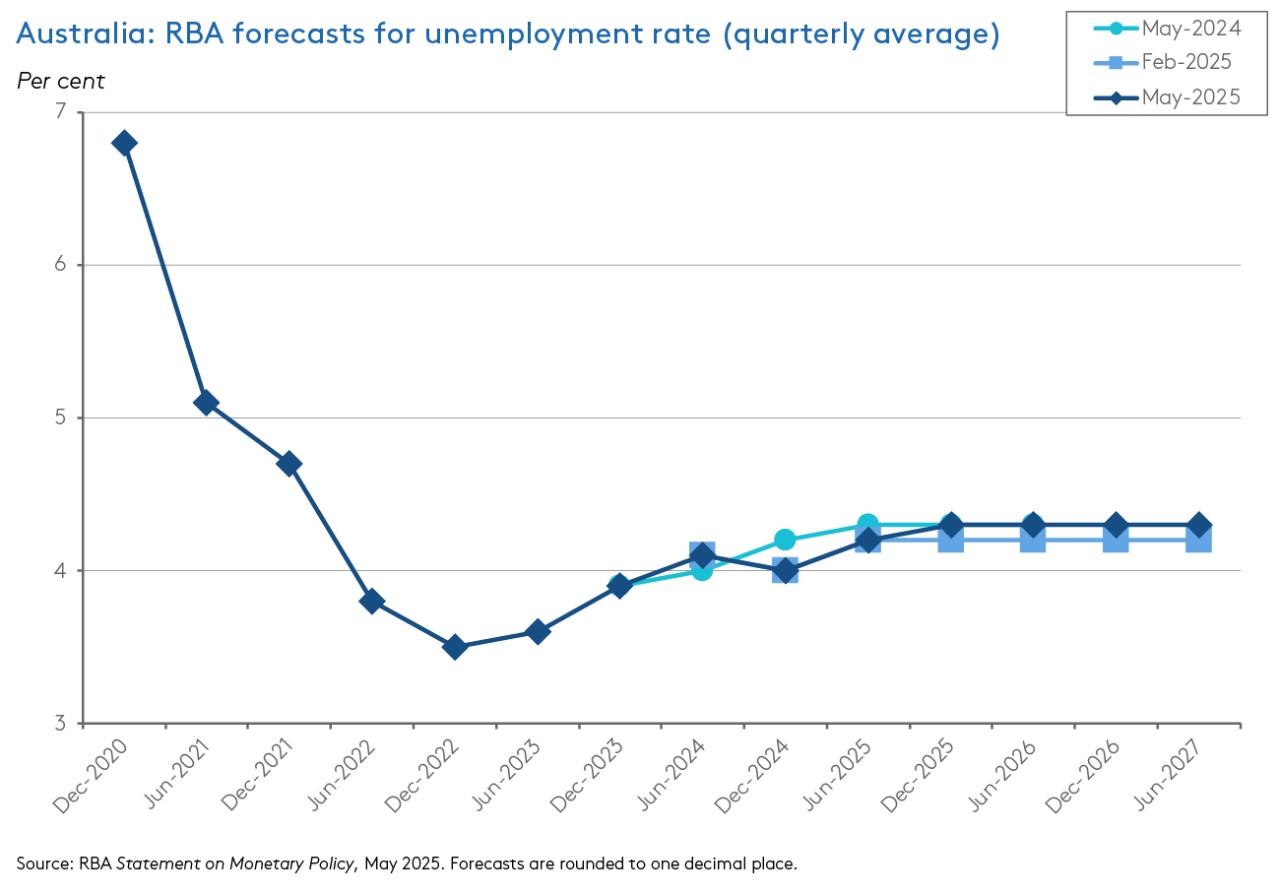

The same forecasts think that the unemployment rate will not move above 4.3 per cent under this scenario, which would leave it more than a full percentage point lower than the average unemployment rate across the 2010-2019 period.

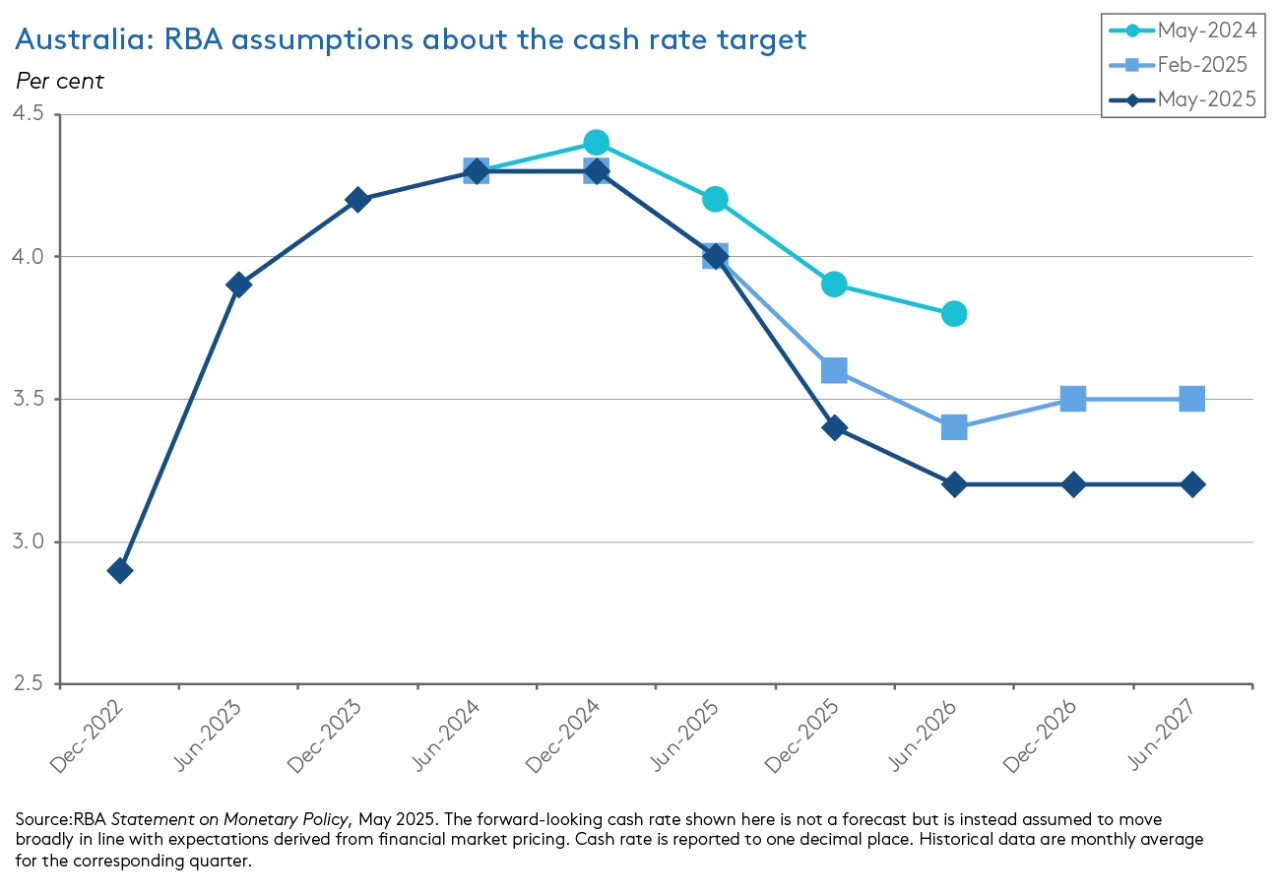

Moreover, the baseline forecast in the May 2025 SMP also thinks this inflation-unemployment profile is compatible with a lower cash rate than was the case back in February; the new market-based assumption is that the cash rate falls to 3.4 per cent by the end of this year and then falls again to 3.2 per cent in 2026.

To be clear, the SMP does acknowledge that there are significant uncertainties around the baseline and that this is more the case than usual. Or, to quote the governor from the same press conference:

“I would say that in the baseline forecast, yes, it’s giving us some confidence that we can get back to a situation where we’re in the middle of the band for inflation and unemployment is still relatively low, but, again, as you go further out it gets more uncertain so we do have to remain data-driven.”

In other words, the RBA is not going to risk hubris by declaring ‘Mission Accomplished.’ And no doubt there is plenty in the economic environment to keep Martin Place worried about the outlook from here, although as discussed last week, the focus has now tilted towards on downside risks to activity. Even so, it is worth acknowledging the success that Martin Place has achieved in navigating that narrow path that Governor Bullock has just bid farewell.

What else happened on the Australian data front this week?

The volume of total new private capital expenditure fell 0.1 per cent over the March quarter 2025 (seasonally adjusted) to be down 0.5 per cent over the year. According to the ABS, expenditure on buildings and structures rose 0.9 per cent in quarterly terms and was up 0.6 per cent on an annual basis, but spending on equipment, plant and machinery was down 1.3 per cent over the quarter and 1.8 per cent lower over the year. By industry, mining capital expenditure was up 1.9 per cent over the quarter but non-mining capex fell 0.9 per cent in quarterly terms. The Bureau said that the Information, media, and telecommunications sector drove the fall in equipment and machinery capex, recording a 17.9 per cent drop as spending retreated from record levels in the December quarter 2024. Relative to the March quarter last year, spending was still 5.2 per cent higher. There was also a fall in business investment in IT equipment and motor vehicles across other services industries.

The ABS said that total construction work done was flat over the March quarter 2025 at $74.4 billion (seasonally adjusted, chain volume terms) and up 3.5 per cent over the same quarter in 2024. Building work done was up 0.9 per cent over the quarter and 2.6 per cent higher over the year. Within that total, residential construction work done was up 1.6 per cent quarter-on-quarter and up seven per cent year-on-year. In contrast, non-residential construction work done was down 0.1 per cent in quarterly terms and 3.9 per cent lower on an annual basis.

The ANZ-Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence Index fell 1.8 points to 87 points in the week ending 25 May 2025. Four of the five subindices fell over the week, led by a 4.9 point drop in ‘short-term economic confidence,’ indicating there was no lift in sentiment in response to the RBA’s 25bp rate cut last week. The only exception was ‘time to buy a major item’ (up 1.7 points). Weekly inflation expectations rose 0.2 percentage points to 4.7 per cent.

Other things to note . . .

- Treasury Secretary Steven Kennedy’s post-Budget economic briefing to the Australian Business Economists. Dr Kennedy discussed the international environment, saying that Australia would have to ‘accept that for the foreseeable future the world will be characterised by a persistent high level of uncertainty, a level not experienced for decades.’ Given that context, he identified three key trends in government policy responses to this challenge: (1) Building resilience by deploying economic reforms to raise the productive capacity of the economy; (2) Pursuing trade and economic diversification; and (3) Investment in deterrence, including through defence spending. In terms of building resilience, the Treasury Secretary thinks that lifting both the rate and stability of productivity growth is key. Kennedy noted the ‘five pillars’ of productivity reform we discussed last week and highlighted current and prospective areas for work including: National Competition Policy, Road user charging, Occupational licensing, and Non-compete clauses.

- The RBA’s Andrew Hauser reflects on a recent trip to China in the immediate aftermath of ‘Liberation Day.’

- On the RBA’s response to US tariffs.

- Australia’s national security and food security.

- The Productivity Commission (PC) has released a new report on Productivity before and after COVID-19. The PC’s focus is the labour productivity ‘bubble’ from 2020 to 2023 which first saw labour productivity rise to a record high from the onset of the pandemic in January 2020 to March 2022 before falling back to its pre-pandemic level by June 2023. The PC splits this bubble into three phases: (1) a ‘reallocation’ phase between December 2019 and December 2020 where productivity growth is explained almost entirely by lockdowns leading to the shutdown of lower productivity industry and a shift in the composition of employment to more productive industries; (2) a ‘productivity gain’ phase between December 2020 and March 2022 when lockdowns were unwound and the recovery in economic activity ran ahead of the recovery in employment, translating into a further increase in productivity; and (3) a ‘productivity loss’ phase between March 2022 and June 2023, when productivity fell as the capital stock failed to keep pace with the rise in hours worked leading to falling capita per worker, and as younger and less experienced workers joined the labour force leading to a fall in the average quality of the workforce. On the policy front, the PC reckons that the rise of the care economy in response to government funding and subsidies has worked to drag down (measured) productivity, while the choice during the pandemic to pursue JobKeeper may have had economic costs in the form of preventing productivity-lifting job reallocations to set against the benefits it delivered in terms of underpinning economic resilience and preserving employment). Interestingly, the PC thinks that other shifts during the pandemic (the disruption to supply chains, the rise in WFH) did not have a significant implication for productivity, although on balance it does think that part-time WFH/hybrid arrangements are probably beneficial for productivity. Overall, the PC’s key judgement is that ‘there are no obvious long-term implications arising from Australia’s productivity performance during the pandemic.’

- Two from the Grattan Institute: worries about inequality and the energy transition and the case for taxing super.

- The AFR continue to debate the merits of the proposed new Super Tax: John Kehoe argues that while there is a case for reform, this is not the way to do it; Miranda Stewart reckons its fair and affordable; Steven Hamilton suggests a better way to tax super capital gains; Richard Holden warns it will raise far less money than Treasury expects; and Robert Breunig suggests six simple proposals for an optimal tax agenda. Meanwhile, over in the Guardian, Greg Jericho is scathing about much of the debate.

- New Zealand’s IMF Article IV and IMF Selected Issues reports.

- The CSIS sets out scenarios that could define 2035: China stalls, US global leadership falters, and trust fails.

- The WSJ’s Grep Ip says that something fundamental has changed in financial markets: the pre-pandemic savings glut is over, governments have to pay up, and big budget deficits are now more dangerous.

- Two new reports from the OECD. Steel Outlook 2025 warns that the global steel industry faces the risk of deepening global excess capacity amid sluggish demand growth. And a look at the environmental impacts, economic costs and international consequences of droughts reckons that economic losses and damages due to droughts may be increasing at an annual rate of more than three per cent, implying that the average drought episode in 2025 is at least twice as costly as it was in 2000.

- An FT Big Read on what the world can learn from China’s manufacturing dominance.

- This week’s Economist magazine looks at the risks to Vietnam’s export boom and Hanoi’s search for new friends.

- New research from Bruegel on sovereign debt sustainability, climate impacts and adaptation.

- A new World Bank report looks at future jobs, robots, AI and digital platforms in the East Asia and Pacific region.

- Does AI progress have a speed limit?

- The MIT Technology Review on AI’s energy footprint.

- An interview with Niall Ferguson.

- The Australia in the World podcast in conversation with Dr John Kunkel (Chief of Staff to former PM Scott Morrison) on the geopolitical and geoeconomic moment facing Australia.

- The latest in Adam Tooze’s occasional series on heterodox economists considers the case of Joseph Schumpeter.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content