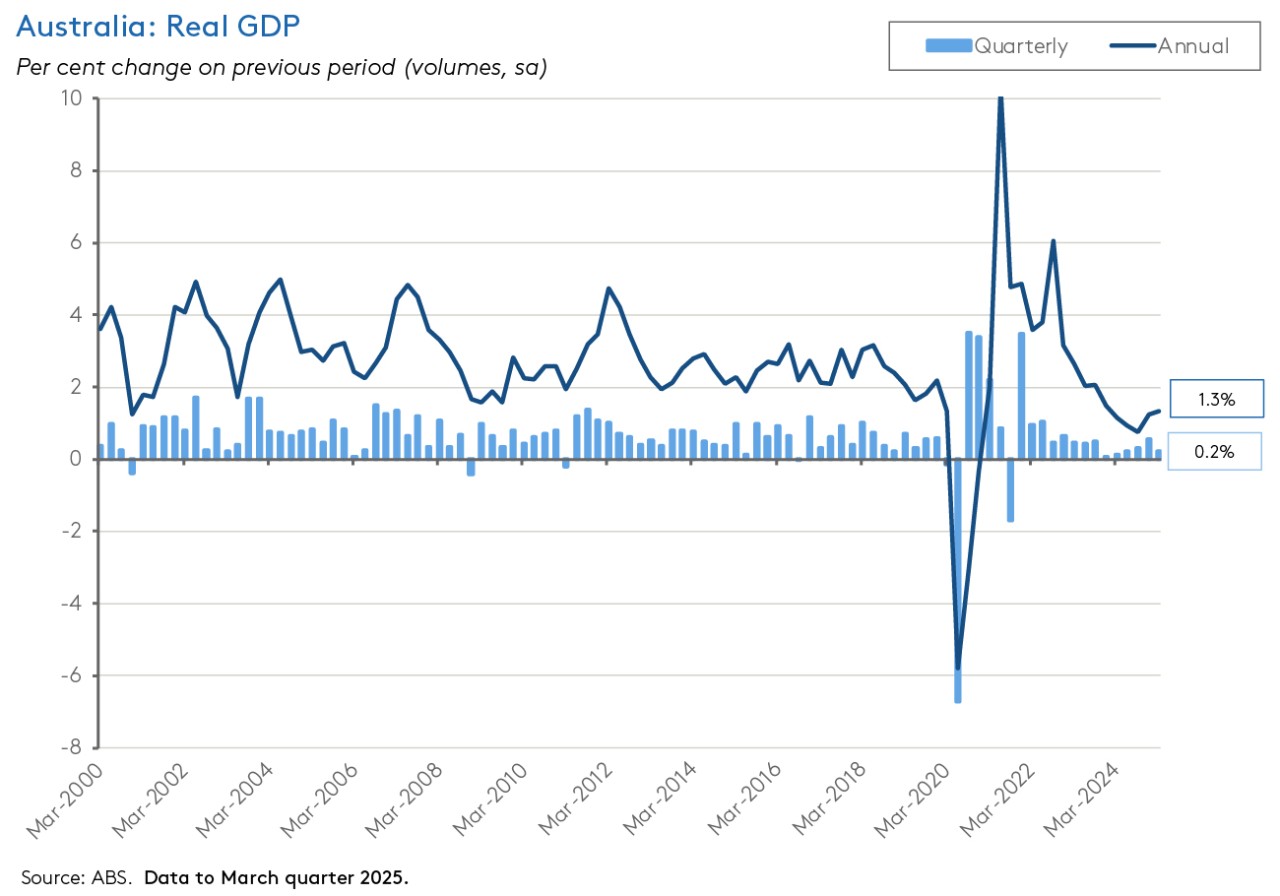

This week’s release of the March quarter national accounts confirmed that the Australian economy got off to a subdued start in 2025. Quarterly growth came in below market expectations at a mere 0.2 per cent while the annual rate of increase was unchanged from the previous quarter at a pretty lacklustre 1.3 per cent. In per capita terms, the economy went backwards once again after having – briefly – registered an increase in the December quarter of last year.

Some of this reflected temporary factors, with the ABS highlighting the depressing impact on growth of adverse weather conditions. And an unusually large negative contribution from public sector demand also added to the soft outcome. The Q1 numbers also predate the removal of election uncertainty and the RBA’s delivery of a second interest rate cut last month, and only partly capture the impact of the initial February easing in monetary policy. At the same time, however, the March quarter data likewise predate some of the worst of the global economic policy uncertainty unleashed by 2 April and ‘Liberation Day.’

While private demand drove what growth there was last quarter – with positive contributions from household consumption, dwelling investment, and non-residential construction – the economy has been tracking weaker than both the markets and the RBA had anticipated. Recall that according to the latter’s May 2025 forecasts in the Statement on Monetary Policy, under the baseline scenario growth is projected to pick up to an annual rate of 1.8 per cent by the June quarter of this year. At the same time, the RBA has repeatedly flagged that it sees ongoing weakness in household consumption as a material risk to this outlook. Yet another quarter of falling per capita consumption will have reinforced that concern.

Taken together, the weak GDP numbers plus the RBA’s declared willingness to contemplate a larger 50bp cut at last month’s Monetary Policy Board (MPB) meeting – as discussed in the Minutes released this week – suggest that the upcoming MPB meeting on 7-8 July remains ‘live’ in terms of a third potential rate cut. Pushing in the opposite direction, last week’s inflation numbers were not particularly helpful to the case for pre-emptive action and another disappointing quarterly productivity reading in this week’s GDP release will have reminded Martin Place of its apprehensions regarding persistent supply side constraints. Reflecting these conflicting signals, markets reacted to the national accounts by pushing up the probability of a July rate cut to more than 90 per cent, even as many RBA-watchers continued to tip the following meeting on 11-12 August as the more likely occasion for the next cut. Timing aside, there is a clear consensus that more policy easing is on its way.

We dig into the GDP numbers in more detail below, analyse the latest MPB minutes, and cast our eye over this week’s Fair Work Commission wage decision. There’s also a roundup of the rest of the week’s data releases plus the regular linkage selection. Finally, a reminder that the AICD’s National Economic Update is coming up on 17 June.

Economic growth was weak in the first quarter

The ABS said that Australia’s real gross domestic product (GDP) rose 0.2 per cent (seasonally adjusted) over the March quarter 2025 to be up 1.3 per cent over the year. Quarterly growth was slower than the December quarter’s 0.6 per cent rate while the annual growth rate was unchanged. Markets had anticipated a stronger outcome: the consensus forecast was for growth of 0.4 per cent quarter-on-quarter and 1.5 per cent year-on-year. The ABS said the subdued read on activity reflected a negative contribution from public demand alongside the adverse impact of extreme weather events on domestic demand and exports. According to the Bureau, weather effects were particularly strong for mining, tourism and shipping.

Australia had exited a seven-quarter-long ‘per capita recession’ according to the December quarter 2024’s national accounts. But the reprieve has proved temporary: By last quarter the pace of output growth once again failed to keep up with population growth, with GDP per capita falling by 0.2 per cent over the previous period and dropping by 0.4 per cent over the year. Indeed, real GDP per capita has now fallen in year-on-year terms for eight consecutive quarters – the last positive result was back in the March quarter 2023.

Another disappointing result came on the productivity front, where GDP per hour worked was unchanged for a second consecutive quarter and down one per cent compared to the March quarter 2024. In the market sector, productivity (measured as GVA per hour worked) did increase by 0.1 per cent over the quarter but that still left it 0.7 per cent lower than in the corresponding quarter last year.

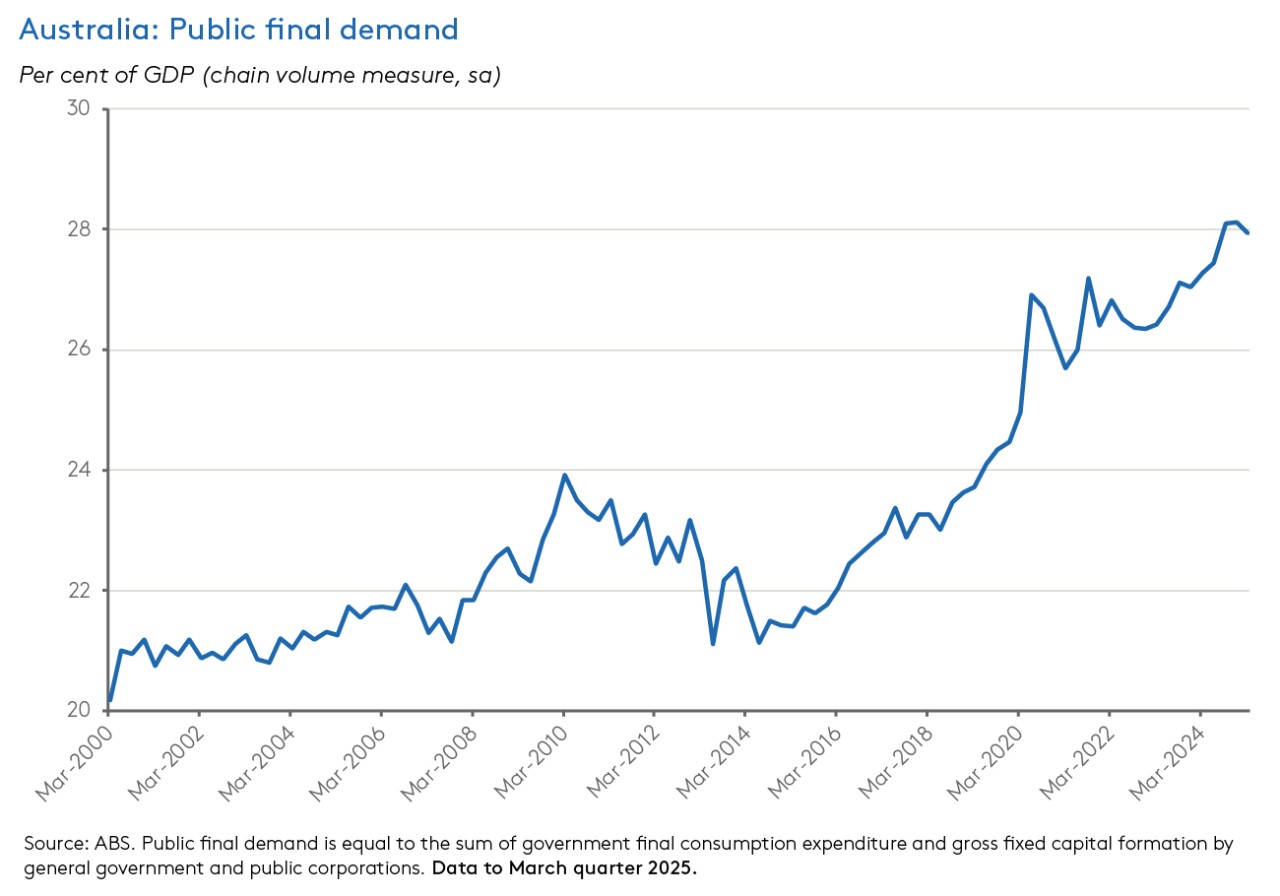

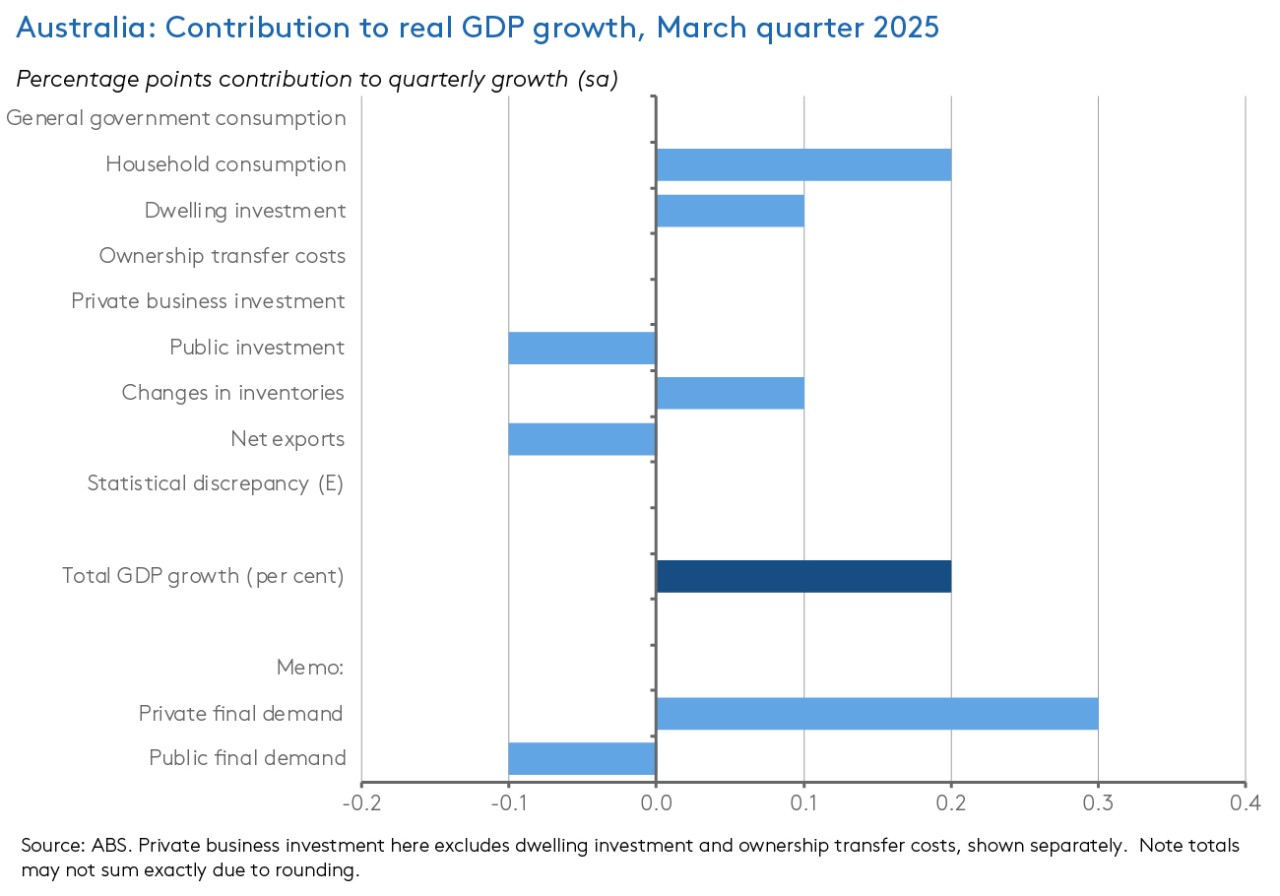

Growth over the March quarter was driven by private sector demand, which contributed 0.3 percentage points to the total outcome. That was offset by a negative (0.1 percentage point) contribution from public sector final demand. According to the ABS, that represented the strongest detraction from growth by the public sector since the September quarter 2017, well before the pandemic. As a result, the hitherto relentless-looking increase in the share of public sector demand in GDP went backwards slightly last quarter.

There was no contribution to quarterly growth from Government final consumption expenditure in the March quarter, with government sector spending flat over the quarter although up 3.4 per cent over the year. The ABS said that state and local governments spent less on social benefits to households, including through lower payments for energy relief, while Commonwealth spending on social benefits remained low with spending on the Medicare Benefits Scheme and the National Disability Insurance Scheme both falling (although Commonwealth spending on defence did continue its steady expansion). Public investment fell two per cent over the quarter, subtracting 0.1 percentage points from growth. The Bureau noted that this reflected a decline in investment by public corporations following record investment in the December quarter, citing energy, telecommunications, rail and road project completions and delays.

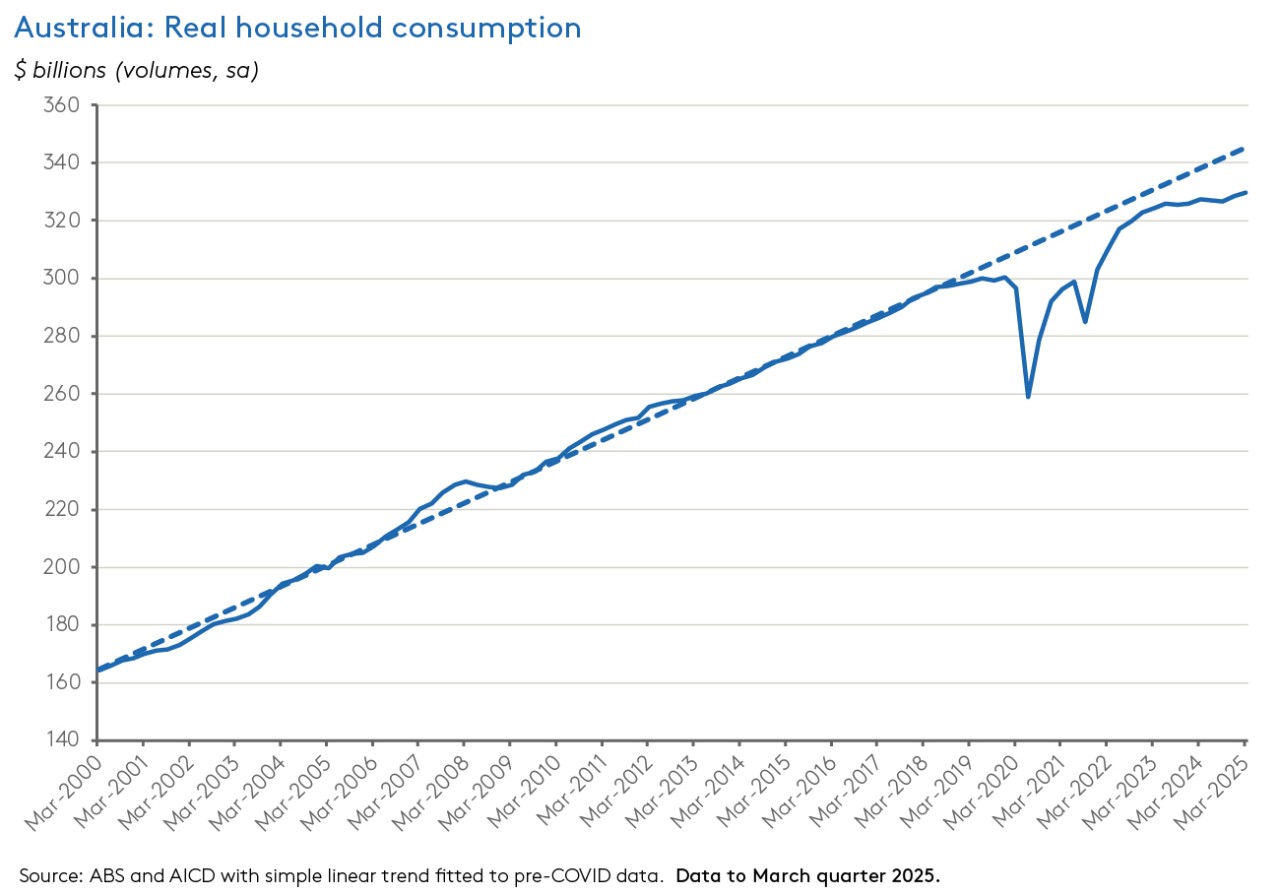

Turning from the public to the private sector, household consumption made the largest positive contribution (0.2 percentage points) to growth over the March quarter. Spending was up 0.4 per cent (down from an upwardly revised 0.7 per cent increase in the December quarter) and rose 0.7 per cent over the year. Within total consumption, spending on essentials grew by 0.4 per cent due in part to greater demand for electricity (in response to warmer than average summer conditions) plus lower energy bill relief payments. Discretionary spending rose by a more subdued 0.3 per cent after the December quarter had seen stronger than usual retail sales.

Overall, the national accounts suggest consumption spending was relatively soft across the start of this year. In terms of levels, real household consumption continues to run below its pre-pandemic linear trend. And on a per capita basis, household consumption spending went backwards again, falling by 0.1 per cent over the quarter and dropping by 0.9 per cent over the year. On an annual basis, real household consumption per capita has now fallen for seven consecutive quarters.

In nominal terms, growth in household disposable income once again outpaced the rise in household consumption, leading to another increase in the household saving ratio last quarter, from 3.9 per cent to 5.2 per cent. Income growth was supported by increases in compensation to employees (up 1.5 per cent over the quarter and 6.5 per cent over the year) and was also boosted by social assistance benefits and non-life insurance claims in response to cyclone and flood damage in Queensland and New South Wales. At the same time, lower interest rates over the quarter meant that dwelling interest income payable fell for the first time since the March quarter 2022.

Private investment rose 0.7 per cent over the quarter and 2.3 per cent over the year, contributing 0.1 percentage points to quarterly GDP growth. Within that total, dwelling investment was up 0.7 per cent in quarterly terms and 5.6 per cent in annual terms while non-dwelling construction rose 1.3 per cent and 1.4 per cent, respectively. Each added 0.1 percentage points to quarterly GDP growth. Their contribution was partly offset by a contraction in capex on machinery and equipment – down 1.7 per cent quarter-on-quarter and down 3.7 per cent year-on-year – which subtracted 0.1 percentage points from quarterly growth.

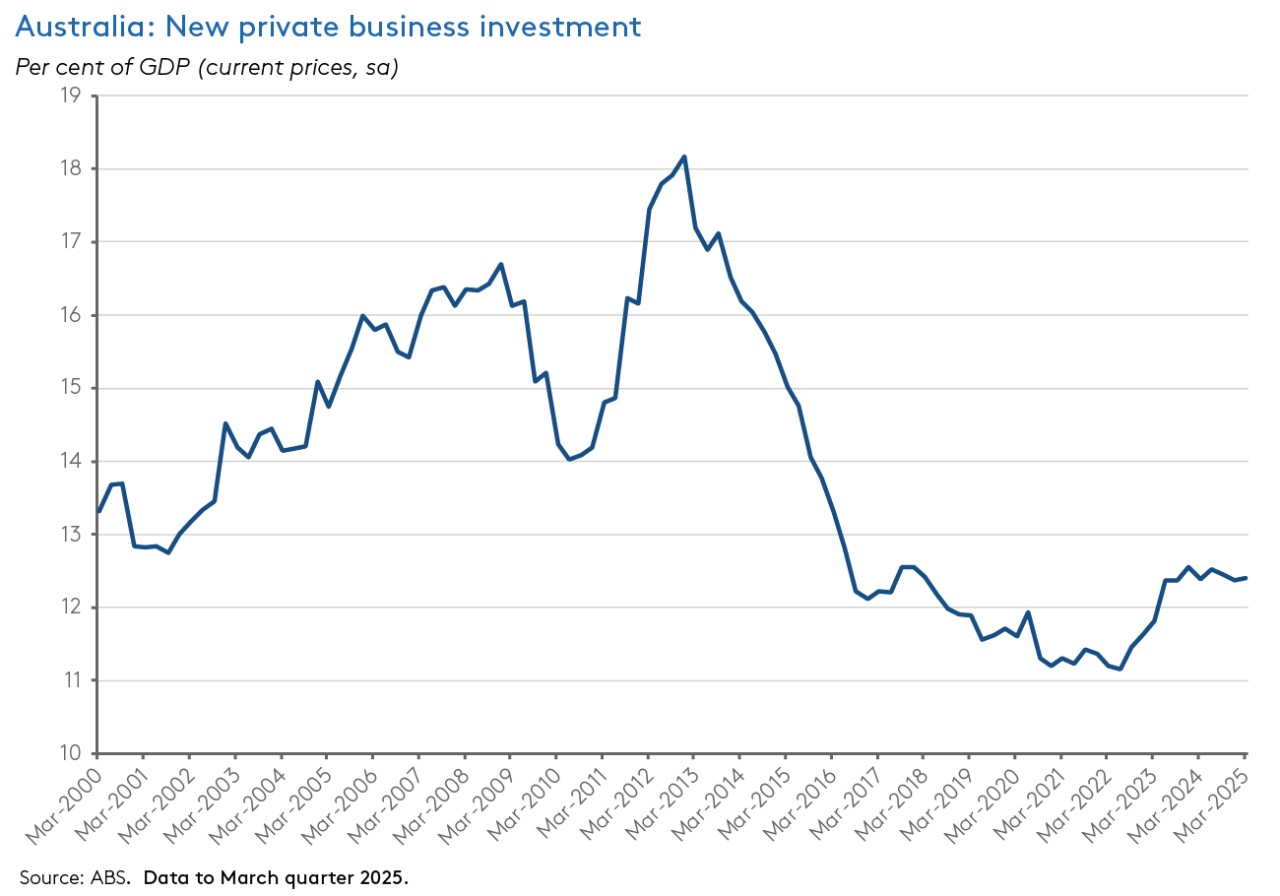

Total private business investment edged higher by 0.1 per cent over the quarter and 0.8 per cent over the year – not enough to have a significant growth impact. Step back a little, and the share of new private business investment in GDP looks to have stabilised at around 12 – 13 per cent of GDP over recent quarters. That marks a modest recovery from its pandemic lows but is not indicative of the kind of sustained surge in capital investment likely to generate a significant uptick in productivity growth.

Rounding off the GDP story, the ABS said that changes in inventories contributed 0.1 percentage points to quarterly growth, with a large build up in mining inventories (as lower export demand plus severe weather disruption leading to port closures delayed shipping) while manufacturing inventories also rose in line with greater production of gold, steel and alumina.

Finally, net trade subtracted 0.1 percentage points from growth last quarter as a decline in exports (lower travel services exports due to lower student spending, and lower coal and LNG exports due to those adverse weather effects again, along with softer external demand) was only partially offset by a smaller decline in imports.

The RBA Minutes: Anatomy of a rate cut

The RBA published the Minutes of the 19-20 May Monetary Policy Board (MPB) Meeting which delivered a 25bp cut in the cash rate target. The Minutes take us through the MPB’s deliberations around the decision, breaking it down into (1) a debate over hold policy unchanged vs cut the policy rate and (2) a debate over a regular 25bp reduction vs an outsized 50bp cut. They also report the MPB reflecting on the impact of the ‘Liberation Day’ US tariffs announced on 2 April, the messy aftermath, and the resulting elevated levels of uncertainty and policy unpredictability.

Starting with the debate over hold vs cut, the Minutes report that the case to leave the cash rate target unchanged rested on three main considerations: (1) the RBA expected headline inflation to return to the top of the two-to-three per cent target band as governments unwound temporary energy subsidies; (2) despite the international turmoil, there had been little evidence of a significant adverse impact on domestic activity; and (3) the central bank judged that the prevailing stance of monetary policy was not ‘very restrictive’ at a 4.1 per cent cash rate. Set against that, the case for a cut rested on three different considerations: (1) actual inflation had demonstrated progress in returning to target while upside risks had failed to materialise; (2) the deterioration in the external environment plus ongoing weakness in household consumption had ‘shifted the balance of risks downwards’; and (3) the case for pursuing a policy of ‘least regret’ in the face of prevailing global uncertainty.

One point of note in the subsequent debate is that according to the minutes, the MPB thought that ‘trends in domestic conditions could, on their own, justify some degree of reduction in the cash rate target at this meeting’ while ‘[d]evelopments in the global economy since the previous meeting strengthened the case for a reduction in the cash rate target.’ Summing up the verdict, the Minutes report:

‘…members judged that the case to reduce the cash rate target was the stronger one. They agreed that monetary policy had been effective in bringing inflation back to target, and that it was no longer necessary to be as restrictive given the current rate of inflation and the staff’s assessment of spare capacity. In addition, members judged that a lower cash rate would also be an appropriate response to the downside risks that had emerged from international developments since the previous meeting.’

Moving on to the debate between 25bp and 50bp cuts, the Minutes report that the case for a smaller move reflected a range of judgements, including: (1) a 25bp cut would be consistent with the technical assumption for the cash rate underpinning the RBA’s baseline forecasts, which had underlying inflation at the midpoint of the target band over the forecast period; (2) it would give some weight to the likelihood that global developments would slow the Australian economy while also recognising the lack of evidence of an adverse impact on domestic demand in the data; (3) it would be in line with market expectations, reinforcing policy predictability at a time of high uncertainty; (4) a smaller cut would be consistent with uncertainties around the supply side of the Australian economy (lacklustre productivity growth, a tight labour market, the possibility that firms’ profit margins would recover faster than expected), plus the risk that disruption to global supply chains could raise prices globally; and (5) it would reduce any risk of the MPB having to subsequently reverse a policy loosening and the impact this would have on households and businesses. Against this, a 50bp cut ‘could be appropriate if members judged that the downside risks stemming from either global or domestic developments warranted easing monetary policy more quickly than assumed in the baseline forecast.’

Summing up the MPB’s decision to opt for a 25bp cut, the Minutes report:

‘…developments in the domestic economy on their own justified a reduction in the cash rate target and…the case for that action was strengthened by developments in global trade policy. However, members were not persuaded that the combination of these was sufficient to warrant a 50bp reduction at this meeting. Members noted the absence of signs in the Australian data to date that global trade policy uncertainty was having a significant negative impact on the economy, and that some plausible adverse scenarios could see upward pressure on inflation. They also judged that it was not yet time to move monetary policy to an expansionary stance…given that inflation was yet to return sustainably to the midpoint of the target range and the staff’s assessment that the labour market was still tight. These considerations and the prevailing global policy uncertainty led members to express a preference to move cautiously and predictably when withdrawing some of the current policy restriction.’

Overall, the Minutes are consistent with our take at the time: the RBA is now considerably more confident about the need to return the cash rate target to a neutral setting compared to the much more cautious position it took at the (pre-Liberation Day) April meeting when the MPB didn’t even discuss the case for a rate cut. Granted, according to the Minutes, the RBA is still planning to operate ‘cautiously and predictably’. And the uncertainty around the outlook means that Martin Place is not yet ready to rush monetary policy settings past neutral and into expansionary territory. But it does stand ready to do so should international developments deliver further downside risks.

The FWC decided on a 3.5 per cent wage increase

The Fair Work Commission (FWC) decided to increase the National Minimum Wage (NMW) and all modern award minimum wage rates by 3.5 per cent, effective from 1 July this year. With the ACTU having sought a 4.5 per cent increase in award wages and employers making the case for a more modest 2.5 per cent rise, the FWC has split the difference.

The Commission said that the ‘principal consideration’ guiding its decision was that the real value of modern award wages had fallen by 4.5 percentage points since July 2021 (although the fall in the real NMW had been smaller at 0.8 percentage points). At the same time, the FWC highlighted what it said was the RBA’s assessment that inflation has sustainably returned to its target range. This, it said, allowed it to address some of the decline in real wages and so avoid a permanent large fall in real living standards for the lowest paid without risking further contributing to persistent high inflation. The FWC says it did take into account Australia’s poor productivity performance, noting that this ‘operated as a restraining factor on the size of the increase’ but added that in its view this mainly applied to the non-market sector, arguing that in the market sector modest growth in labour productivity suggested ‘some capacity for business to pay for a modest increase in real minimum wages.’

While the NMW only applies to an extremely small share of the workforce (less than 0.25 per cent), modern awards apply to about 20.7 per cent of all employees in Australia, or around 2.6 million employees. According to the Commission, the modern award-reliant workforce has markedly different characteristics than the workforce as a whole: it is ‘disproportionately female (58.6 per cent), more than two-thirds (69.6 per cent)…work part-time hours, more than half (52.8 per cent) are casual employees and more than a third (35.6 per cent) are low-paid (earning less than $25.49/hour in May 2023, or less than two-thirds the median.’ By industry, the four sectors of Accommodation and food services, Health care and social assistance, Retail trade and Administrative and support services account for more than two-thirds of all modern-award reliant employees. Together, those characteristics mean that the wages of modern award-reliant employees only account for about 10.5 per cent of the national wage bill.

As result, the FWC reckons that the direct implications of award decisions on national wage growth are limited. For example, calculations by the Commission estimate that the 3.75 per cent increase it awarded last year contributed just 0.36 percentage points to wage growth as measured by the Wage Price Index (WPI) over the 12 months to the March quarter this year – or about 11 per cent of the total increase in the WPI. In addition, however, the decision also has indirect implications. The FWC reckons that another 2.3 per cent of the workforce (about 0.3 million employees) are covered by enterprise agreements that prescribe wage increases in line with FWC Review decisions. And while it is difficult to measure, there is also the likelihood of some spillover or signalling effects from FWC decisions to individual arrangements and enterprise agreements.

What else happened on the Australian data front this week?

Australia’s current account deficit shrank by around $1.7 billion last quarter, falling from $16.3 billion in the December quarter last year to a shortfall of $14.7 in the March quarter 2025 (seasonally adjusted). That reflected a small decline in the trade surplus due to lower commodity prices (from $5.4 billion to $5.2 billion) that was more than offset by a narrowing in the net primary income deficit due to lower profit flows to foreign direct investors (from $21.6 billion to $19.4 billion), with softer coal prices and profits playing a leading role in both cases. The ABS also said that Australia’s terms of trade edged higher by 0.1 per cent over the quarter to 91.1, although this still left them down over the year. The Bureau also reported that Australia’s net international liability position remains at historically low levels: at $672.6 billion it is at its lowest level since the June quarter 2008.

The ABS also reported that Australia’s merchandise trade surplus shrank to $5.4 billion in April 2025 (seasonally adjusted), down $1.5 billion from the previous month. Goods exports were down 2.4 per cent over the month, reflecting a fall in non-monetary gold sales, while goods imports rose 1.1 per cent, led by an increase in purchases of capital goods.

New Business Indicators from the ABS for the first quarter of this year. Company operating profits fell 0.5 per cent over the quarter (seasonally adjusted, current prices) and were down five per cent over the year. Wages and salaries were up 1.4 per cent quarter-on-quarter and 5.7 per cent higher year-on-year.

The ABS also released Government Finance Statistics for the March quarter 2025. The general government net operating balance has improved by $2.9 billion since the December quarter last year, with the deficit narrowing to just $0.7 billion.

Cotality (formerly CoreLogic) said that its National Home Value Index (HVI) rose 0.5 per cent over May 2025 to be up 3.3 per cent over the year. Although the latter was the lowest rate of annual growth since August 2023, recent momentum in house prices following the RBA’s February and May 2025 rate cuts means that the national HVI has now risen 1.7 per over the first five months of this year. The Combined capitals index was also up 0.5 per cent over the month and was 2.6 per cent higher in annual terms. Growth in values was broad based last month: every capital city saw dwelling values rise by 0.4 per cent or more. And as well as values, auction clearance rates also picked up after the RBA’s 25bp May rate cut. Meanwhile, in the rental market the monthly pace of rental growth eased to 0.4 per cent last month, down from the 0.6 per cent rate of the previous three months. That slowdown came despite rental vacancy rates remaining close to historic lows: vacancy rates are currently below two per cent in every capital city compared to their decade cross-city average of 2.6 per cent. Cotality explains this apparent paradox in terms of the impact of affordability constraints plus slowing net overseas migration – noting that the same factors are likewise serving to constrain the current rate of growth in home values despite the prospect of further rate cuts from the RBA.

ANZ-Indeed Australian Job Ads fell 1.2 per cent over the month in May 2025 to an index value of 113.6 (seasonally adjusted). Last month’s drop follows a downwardly revised 0.3 per cent monthly decline in the previous month and the Job Ads series has now fallen to its lowest level since March 2021, although ANZ also notes that the series has broadly remained in a tight range since mid-last year.

The ANZ Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence Index fell 0.6 points to 86.4 in the week ending 1 June 2025. The small decline in the index reflected falls for four of the five subindices, with only short-term economic confidence’ ticking up by 1.2 points. The largest fall was registered by ‘future financial conditions’ which declined by 3.2 points. ANZ noted a convergence in confidence across household cohorts, with a decline in the confidence of outright homeowners and a rise in the confidence of mortgage holders. The latter is now at its highest level in three years, likely reflecting the February and May 2025 two rate cuts from the RBA. Weekly inflation expectations rose 0.3 percentage points to five per cent.

In April 2025, the ABS’s Monthly Household Spending Indicator (MHSI) rose 0.1 per cent (current price, seasonally adjusted) over the month to be up 3.7 per cent over the year. The Bureau said that a rise in spending on services was partly offset by a fall in goods spending. The MHSI will replace the ABS data on retail trade from August this year.

Last Friday, the ABS said that retail turnover fell 0.1 per cent (seasonally adjusted) over the month of April 2025 but was still up 3.8 per cent year-on-year. That was markedly weaker than the consensus forecast for a 0.3 per cent rise in spending. The Bureau noted that the easing in retail spending in April was led by clothing, footwear and personal accessory retailing – retailers told the ABS that a warmer-than-usual April had likely postponed spending on winter clothes – along with lower spending in department stores. As noted above, the future trajectory of household consumption is one of the key uncertainties around the domestic economic outlook, and to date there is no sign of a strong rebound.

Also last Friday, the ABS reported that the number of total dwellings approved fell 5.7 per cent over the month of April 2025 to 14,633. That was 7.6 per cent higher than the number of approvals in the same month last year. At 9,349, approvals for private sector houses were up 3.1 per cent in monthly terms and 4.6 per cent higher in annual terms. Approvals for private sector dwellings excluding houses fell 19 per cent over the month to 4,999. But that was still 14.3 per cent higher over the year.

Other things to note . . .

- Sarah Hunter, RBA Assistant Governor (Economic) gave a speech exploring Australia’s links with the world economy. Hunter sets out the five main transmission channels through which current international developments will impact the global and Australian economies: (1) A realignment in global trade flows and a reallocation of production across countries; (2) shifts in consumption patterns in response to changing prices; (3) delays to major consumption and investment decisions in response to higher uncertainty; (4) any offsetting fiscal and monetary policy responses; and (5) a re-pricing of financial assets leading to changes in financial conditions. The RBA’s best guess is that the net effect of these changes at the global level is that the forces depressing demand and putting downward pressure on prices will dominate those disrupting supply and exerting upward pressure, leading to a net dampening of tradables prices. The direct impact of trade shifts on Australia is expected to be muted due to our limited trade ties to the United States and our resource-heavy export mix. Higher global uncertainty is likely to take a greater toll on domestic investment and a more modest toll on domestic consumption. And while the exchange rate is likely to assume its usual role as a shock absorber, weaker demand for US assets has shifted this relationship somewhat relative to past experience.

- The AFR asks, has Treasury lost its Mojo?

- ABS Insights into Government Finance Statistics for the first quarter of this year.

- The ASPI Defence budget brief 2025-26. And the Minister for Defence Industry’s (defensive – sorry, couldn’t resist) speech at this week’s ASPI conference on preparedness and resilience.

- Chris Murphy has some alternative proposals for reforming superannuation tax concessions.

- The June 2025 edition of the OECD Economic Outlook. The OECD reckons that the ‘global outlook is becoming increasingly challenging’ due to higher trade barriers, tighter financial conditions, weaker business and consumer confidence, and elevated policy uncertainty. Based on the assumption that tariff rates are sustained at their mid-May 2025 levels, the OECD has downgraded its growth projections. It now reckons that global growth will slow from 3.3 per cent last year to 2.9 per cent this year and next. Back in March, it thought the global economy would expand by 3.1 per cent this year and 3.3 per cent in 2026. And while the OECD is still forecasting inflation to return to central bank targets in most countries by next year, it now thinks it will take longer to reach those targets, and in the countries most exposed to tariffs it warns inflation could rise before falling. In the case of Australia, the forecast changes are modest. The OECD now thinks that growth will pick up from 1.1 per cent in 2024 to 1.8 per cent this year and 2.2 per cent next year. For comparison, in its March 2025 forecasts, the OECD expected growth to run at 1.9 per cent this year and 1.8 per cent next year. The new forecasts for inflation see headline inflation running at 2.3 per cent over 2025 and 2026, little changed from March projections of 2.4 per cent and 2.2 per cent, respectively.

- The Economist magazine has a special report on a new financial order which looks at the rise of ‘new financial giants.’

- Also from the Economist, the gig economy of crime.

- The WSJ says Wall Street is sounding the alarm on US debt.

- Related, a look at US sovereign credit default swap (CDS) spreads.

- On fiscal stagnation.

- The latest (June 2025) edition of the IMF’s Finance & Development magazine focuses on the EU and on demographic change.

- The FT’s Martin Wolf in conversation with Alan Taylor, now of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee.

- Is Feudalism our future?

- Remembering Stanley Fischer. FT obit, WSJ obit.

- Duncan Weldon explains why liberal capitalist economies (used to?) win total wars.

- The Odd Lots podcast asks, why is it so hard for Apple to move production from China to India?

- A little while ago I linked to the Past Present Future podcast series on globalisation. Now there is a new series, politics on trial, which to date has covered the trials of Socrates, Joan of Arc, Thomas More and Mary Queen of Scots.

- The 1000th episode of Econtalk.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content