Although the economy is showing positive signs of recovery, its future growth prospects are largely tied to COVID-19 and federal fiscal policy, writes AICD chief economist Mark Thirlwell.

Australia’s near-term economic outlook brightened in late 2020. Positive developments on the public health front have led to the easing of lockdown restrictions. This, plus good news on the development of COVID-19 vaccines and the lift to sentiment generated by October’s budget, have all delivered a rise in consumer and business confidence.

There are also positive signs coming from the housing and share markets. Granted, concerns remain around what looks set to be a harsh, pandemic-ridden winter across swathes of the Northern Hemisphere. And there is the risk of new outbreaks here in Australia. But overall, a run of good news on the domestic front has prompted upgrades to growth forecasts for 2021. It follows that two of the key near-term drivers of Australian growth prospects for 2021 are the trajectory of COVID-19, along with the timing and logistics of plus public reaction to the hoped-for roll-out of vaccination programs.

A third critical factor is the future of policy support for the economy. Easy monetary conditions look to be locked in for at least the next three years. In November, the Reserve Bank of Australia added to its 19 March emergency response package with further rate cuts plus the announcement of a new $100b program of asset purchases. Aggressive forward guidance, linking the prospect of any future monetary tightening to a sustained fall in unemployment and the return of actual inflation to the RBA’s target band, signal that Martin Place expects current policy settings to persist.

The Treasurer has likewise linked the future of federal fiscal policy to labour market conditions, although Canberra is hoping it can constrain its extensive budgetary largesse to be as “timely, temporary and targeted” as possible. That focus means that while total COVID 19-related stimulus is scheduled to surge to more than $145b in 2020–21, it is then estimated to fall to less than $47b in 2021–22. Negotiating this decline in fiscal aid, and in particular the withdrawal of the JobKeeper program, which the RBA reckons saved at least 700,000 jobs in the short run, will be an early test of the resilience of the recovery.

Growth factor

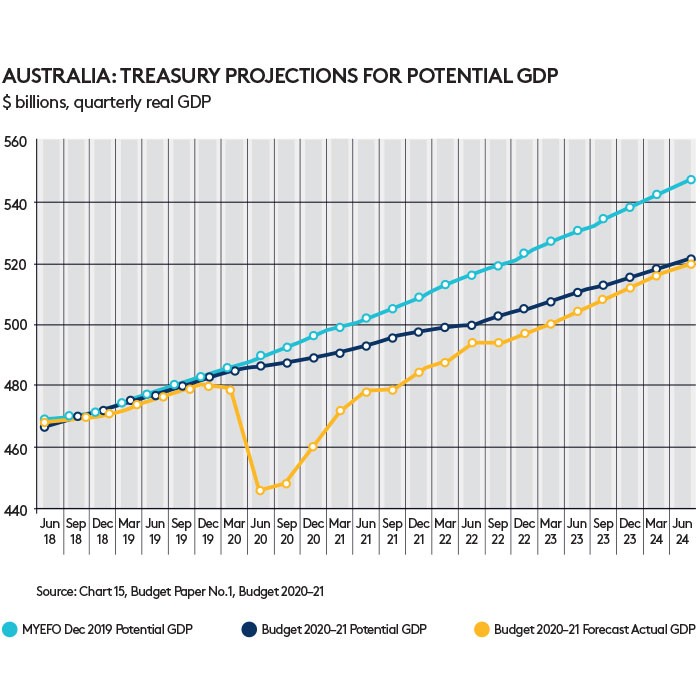

Beyond that, prospects will also start to be influenced by developments in the economy’s underlying growth potential. Unfortunately, there are reasons for concern. In particular, Treasury’s latest estimates, as set out in the 2020–21 budget, are that potential growth will fall below two per cent per annum in the near term before only gradually returning to 2.75 per cent. Potential growth is sometimes described in terms of the “three Ps” (population growth, participation rate, productivity) and COVID has been bad news for least two of these.

Start with population. Treasury expects net overseas migration (NOM) to fall from a net inflow of 154,000 in 2019–20 to net outflows of 72,000 in 2020–21 and 22,000 in 2021–22. NOM typically accounts for 60 per cent or more of population growth, so total population growth is now expected to fall to its lowest rate in more than a century, dropping from 1.2 per cent in 2019–20 to 0.2 per cent in 2020–21 and 0.4 per cent in 2021–22.

NOM is likely to be constrained beyond that by economic uncertainty and weak labour market conditions. With population growth perhaps further weighed down by lower domestic fertility as some families delay having children in response to the pandemic, Treasury predicts a permanently lower Australian population — smaller by about 1.6 million people by 2029–30 relative to the pre-COVID projections. The second and related demographic headwind for potential growth is a drop in the trend participation rate, as lower NOM leads to a change in the age structure of our population.

Productivity precipice

That means the third “P” — productivity growth — will have to do more work to support Australia’s growth performance. Treasury’s assumption is that labour productivity growth will converge over a 10-year period to an annual rate of about 1.5 per cent, its 30-year average. Clearly, there are significant downside risks.

Australia, like most other advanced economies, has not enjoyed a particularly strong productivity performance in recent years. There is the prospect that here, too, the pandemic will deliver further headwinds. The most direct risk is that higher uncertainty and lower growth will further inhibit an already weak performance by business investment, leading to a lower national capital stock and therefore less capital per worker. There’s also the danger that the pandemic will further erode the economy’s underlying dynamism. For example, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission and others have warned that the differential impact of COVID-19 will tend to favour large firms over small and incumbents over challengers, undermining competitive forces in the economy.

A further complication is the deterioration in the bilateral relationship with Australia’s most important trading partner. More barriers to trade with China are not only bad news for impacted exporters in the short run, but also risk turning into a larger economic drag in the longer term through harmful spillover effects on investment and productivity growth. But there are at least two reasons to hope for offsetting positive developments on the productivity front. One is the impetus to economic reform provided by COVID-19. An early example of this is the recent NSW government initiative to tackle stamp duty, widely viewed as one of the most economically inefficient of Australian taxes.

The second cause for optimism is that we might derive significant productivity payoffs from new ways of working unleashed by the pandemic as businesses fast-track digital and other innovations. Bill Gates has predicted more than 50 per cent of business travel and 30 per cent of in-office days will “go away” as we start to do things differently. If so, perhaps productivity could even outperform past results.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content