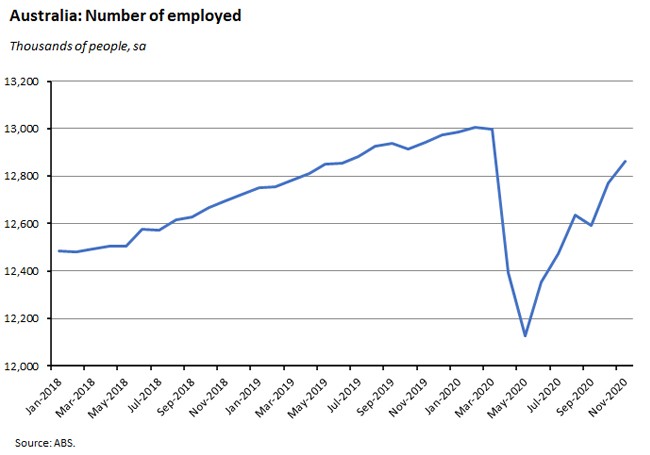

Employment rose by 90,000 people in November, the participation rate returned to a record high, and the unemployment rate fell to 6.8 per cent as for a second consecutive month the labour market delivered a positive surprise.

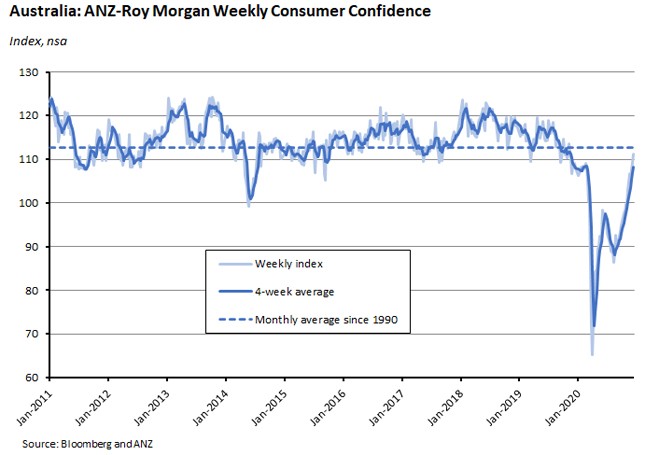

Better economic news over the past two months also saw Treasury upgrade its forecasts in the 2020-21 MYEFO and scale back the forecast budget deficit for this year by more than a percentage point of GDP. In more good news from the labour market, payroll jobs rose by 0.4 per cent over the fortnight ended 28 November and are now just two per cent below where they were in mid-March. The Composite PMI hit a five-month high in December, indicating that business activity continued to accelerate into the final month of the year. The minutes from the RBA’s 1 December meeting depict a central bank that has become more optimistic about the pace of Australia’s economic recovery, but one that also continues to warn that the same recovery will be ‘uneven and protracted,’ and that expects to leave the cash rate unchanged for at least three years. The ANZ-Roy Morgan Weekly Consumer Confidence Index hit a new high for the year, indicating that households are ending 2020 on a positive note. The latest ABS survey of the impact of COVID-19 on Australian businesses shows the share of businesses reporting falling revenue continued to fall this month, although one in four firms are still relying on government wage subsidies.

This week’s readings include more ABS data on the labour market, Treasury’s first population statement, the economics of ‘lockdown lite’, forces shaping the post-COVID future, and an assessment of the risks around inflation. I also look back on some of the economics and other books that I’ve read this year and contemplate my summer reading list.

This is the final edition for 2020 and also the final note before the Weekly heads off on its summer holidays. Many thanks to readers for subscribing and also for your support for the Dismal Science podcast as well as for all of the useful comments and helpful feedback I’ve received over what has been an unprecedented year for both the Australian and global economies. The Weekly will return in February 2021 and until then, I wish you and yours a happy and peaceful holiday season. In the meantime, if you’re missing an economics fix, there will be a final bumper episode of the Dismal Science to close out the year.

What I’ve been following in Australia . . .

What happened:

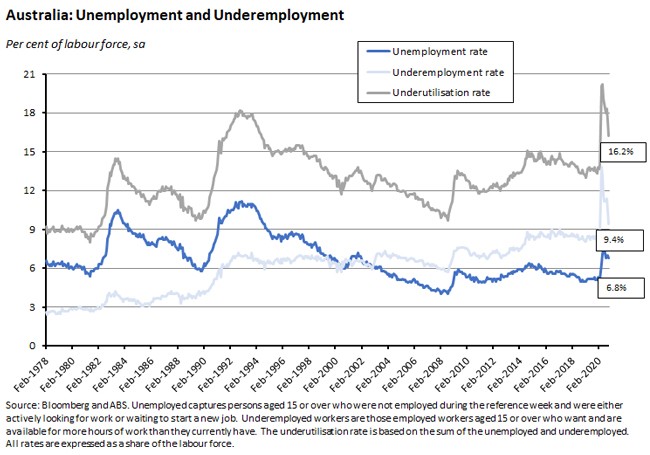

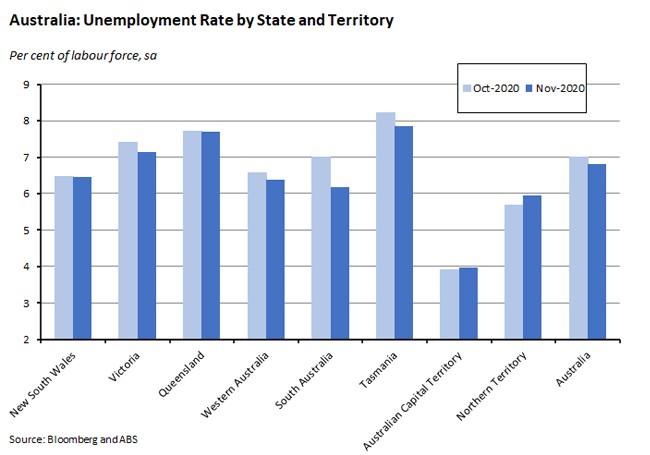

According to the ABS, Australia’s unemployment rate dropped to 6.8 per cent in November from seven per cent in October. The underemployment rate also fell by one percentage point, to 9.4 per cent, taking the underutilisation rate down to 16.2 per cent.

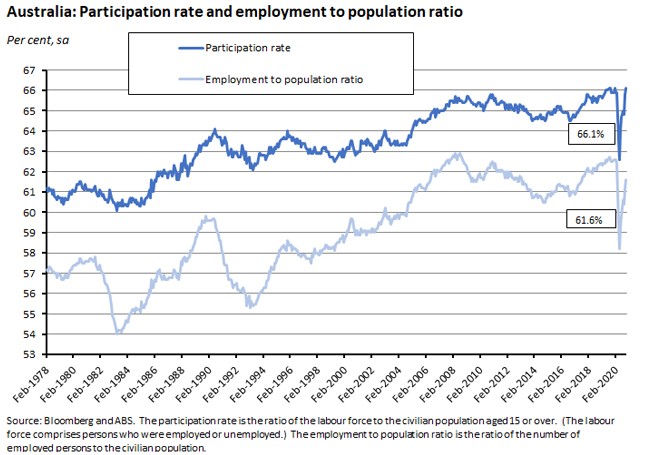

The participation rate rose by 0.3 percentage points to 66.1 per cent while the employment to population ratio increased to 61.6 per cent.

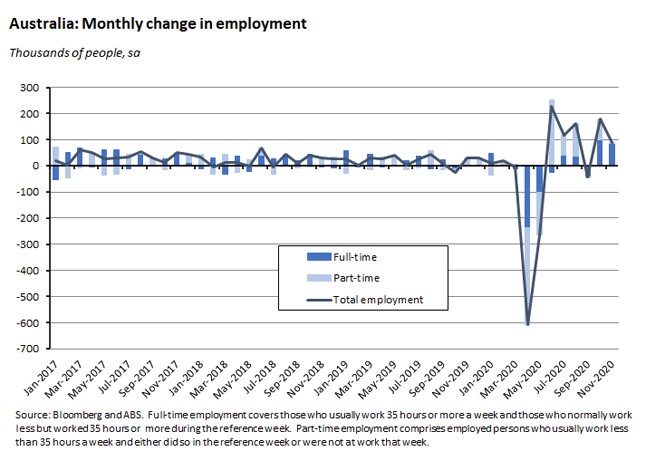

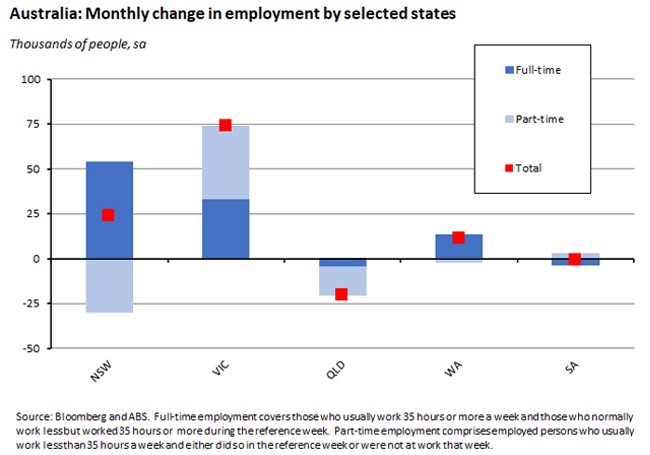

Employment in November increased by 90,000 people (seasonally adjusted) with full-time employment rising by 84,200 and part-time employment growing by 5,800.

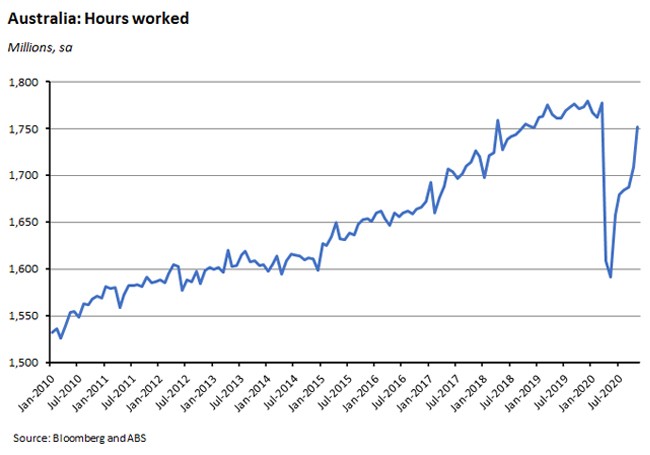

Monthly hours worked in all jobs rose 2.5 per cent lasts month to 1,752 million hours.

By state, employment increased by 74,000 people in Victoria and by almost 24,000 in New South Wales.

Victoria’s unemployment rate fell to 7.1 per cent in November, while there were also falls in Western Australia, South Australia and Tasmania.

Why it matters:

This marked a second consecutive strong labour market report that also comfortably beat market expectations: the median forecasts were for an unchanged unemployment rate and an increase in employment of just 40,000 persons.

As well as the drop in the headline unemployment rate to 6.8 per cent, there was an even bigger decline in underemployment, and as a result the underutilisation rate is now at its lowest since March this year. The ongoing recovery in the Victorian labour market was a big part of the story.

Encouragingly, more Australians are returning to the labour force with the participation rate back up to the record high of 66.1 per cent it last reached back in January this year.

Total employment is now about 143,000 below its pre-COVID levels. The recovery has been stronger for part-time than full-time work, with full-time employment still down 161,000 relative to pre-virus outcomes while part-time employment is now almost 18,000 higher than it was before the pandemic.

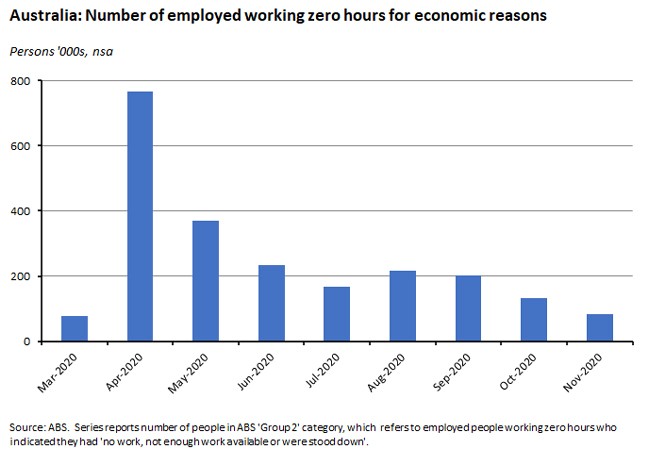

Another welcome sign of labour market normalisation is the continued fall in the number of Australians working zero hours for economic reasons. After hitting a high of around 767,000 people in April this year, that number has now fallen to below 82,000.

While the labour market is recovering, it remains far from fully recovered, and with both fiscal and monetary policy now conditional on the labour market returning to pre-pandemic levels, the case for continued policy support remains firmly in place. Even so, the strong pace of recovery seen over the past two months is very encouraging and offers grounds for hope that the recovery process will continue to beat both current expectations and past labour market performance.

What happened:

The Treasurer released the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO) for 2020-21, updating the outlook presented in the 6 October Budget.

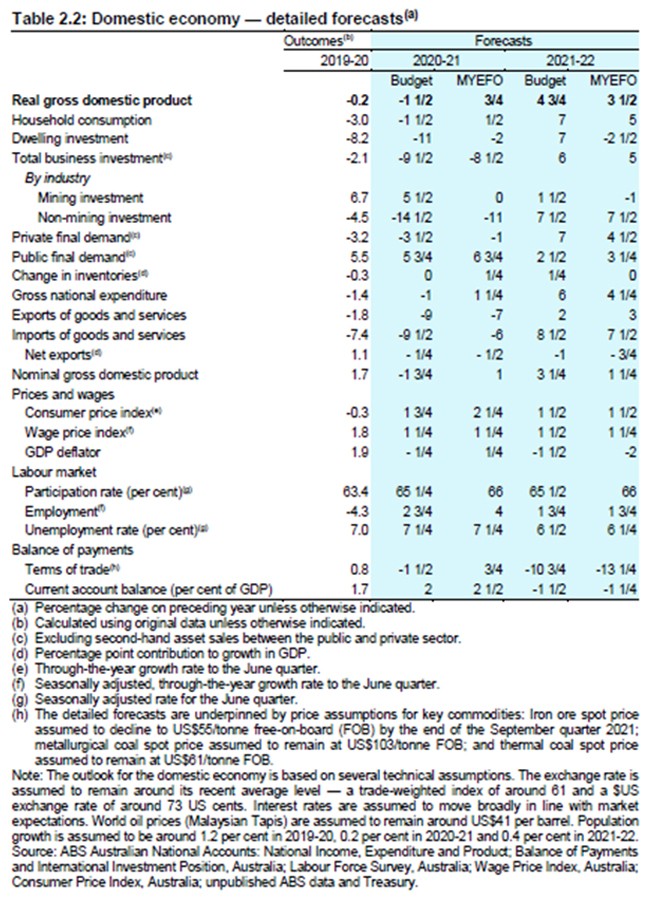

Treasury has now upgraded its forecasts for the Australian economy after considering the implications not only of the Q3 GDP result but also the more recent run of activity data, as well as positive news on vaccines and the impact on business and consumer confidence. Consistent with the assumptions made in Budget 2020-21, the economic outlook once again assumes that while there will be localised outbreaks of COVID-19 over the forecast period these will be contained and while a COVID-19 vaccine is now expected to be available in Australia by March 2021, a population-wide vaccine program is still anticipated to be fully in place by late next year.

Real GDP is now forecast to shrink by 2.5 per cent in 2020 (up from a contraction of 3.75 per cent in the budget) and to grow by 4.5 per cent next year (compared to a budget forecast of a 4.25 per cent rise). Over financial year 2020-21, the economy is now expected to grow by 0.75 per cent instead of shrinking by 1.5 per cent, while in 2021-22 growth is expected to run at 3.5 per cent instead of 4.75 per cent. Sitting behind those stronger real GDP growth numbers is an upgrade to household consumption, which is now forecast to rise by 0.5 per cent in 2020-21 instead of contract by 1.5 per cent, and an improved profile for dwelling investment, with the expected contraction now two per cent instead of 11 per cent. And there has also been a modest change to the forecast decline in business investment.

The nominal outlook for the economy has also been upgraded, with Australia’s terms of trade now projected to rise by 0.75 per cent this financial year instead of fall by 1.5 per cent, reflecting stronger than expected commodity prices (particularly the iron ore price). As a result, nominal GDP is now expected to rise by one per cent over 2020-21 instead of falling by 1.75 per cent.

The outlook for the labour market has also improved, with the unemployment rate now forecast to peak at 7.5 per cent in the March quarter of next year, down from the eight per cent peak forecast at the time of the budget.

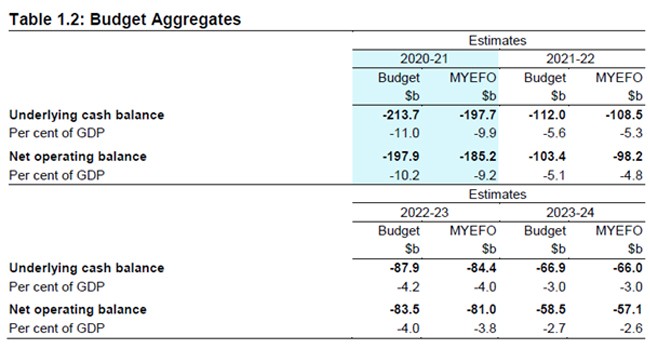

Better than expected consumption demand, higher than anticipated commodity prices and a somewhat healthier labour market have all had a positive impact on the budget bottom line. Total budget receipts are now expected to be $9.5 billion higher in 2020-21 than at the time of the budget (and $22.1 billion higher over the forward estimates period to 2023-24), driven largely by a $3.4 billion improvement in company tax receipts and a $3.2 billion improvement in GST receipts in the current financial year.

At the same time, total cash payments are forecast to be $6.5 billion lower in 2020-21 and $3.6 billion lower over the forward estimates period. The main factor here is the JobKeeper scheme, where payments are now expected to be $11.2 billion lower in 2020-21 as businesses and employees both transition off the scheme at a more rapid rate.

The net effect of those changes is that the underlying cash deficit in 2020-21 is now expected to be $16 billion or 1.1 per cent of GDP smaller than forecast at the time of the budget: it will now ‘only’ be $197.7 billion or 9.9 per cent of GDP. Net debt as a share of GDP will also be lower this financial year, at 34.5 per cent of GDP instead of the 36.1 per cent projected in the budget papers. By 2023-24, however, the deficit as a share of GDP is expected to be more or less in line with October’s forecasts while the net debt to GDP ratio is expected to differ by less than one percentage point from Budget 2020-21’s projection.

Why it matters:

It’s been less than three months since the budget, but the better economic news over that time has driven significant upgrades to Treasury’s near-term expectations for the economy and – as a result – to the budget bottom line for the current financial year. That still leaves the economy running large – but necessary – budget deficits of course. And beyond this financial year, the upgrades to the fiscal projections are rather more modest.

What happened:

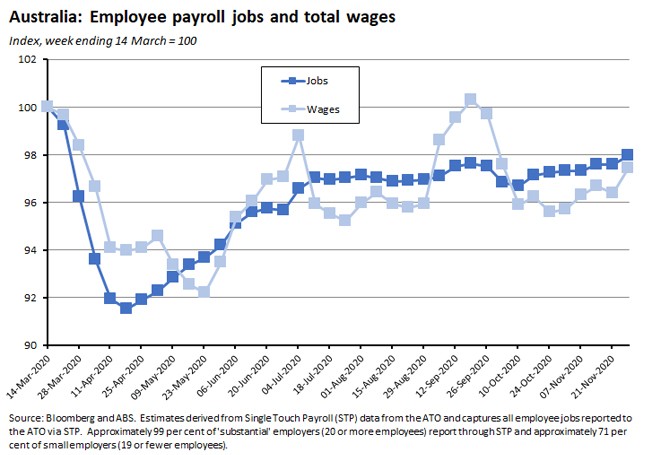

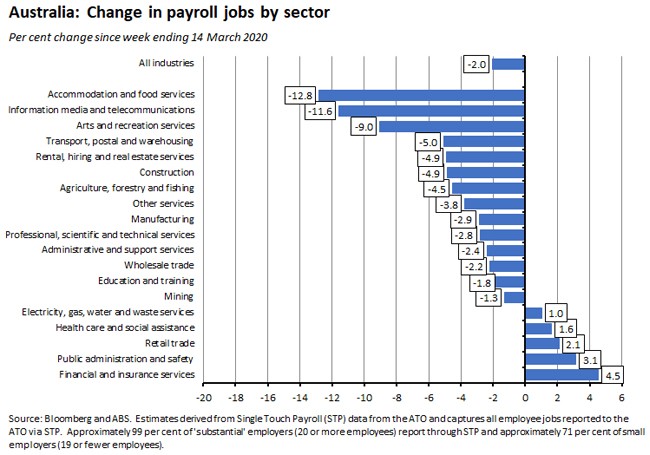

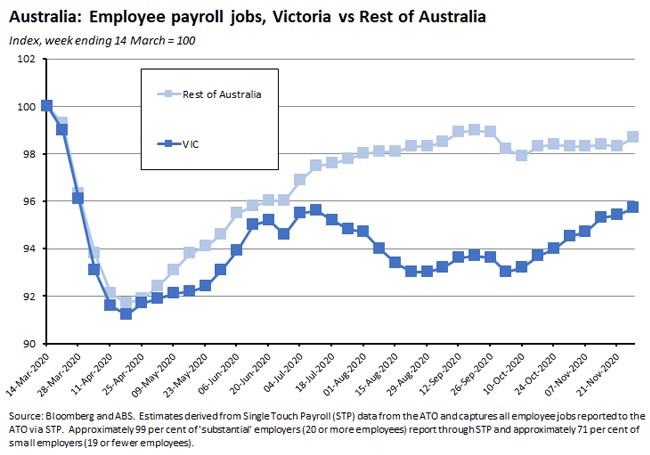

The ABS said that between the week ending 14 March 2020 and the week ending 28 November 2020, the number of payroll jobs decreased by two per cent and total wages paid fell by 2.6 per cent.

By 28 November there were approximately 220,000 fewer payroll jobs than on 14 March.

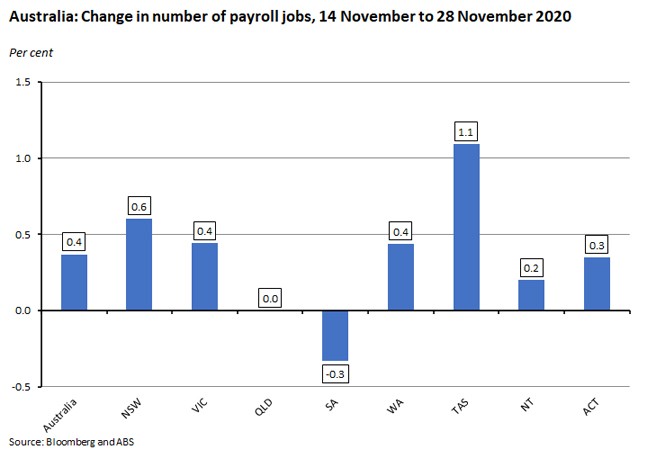

Over the most recent period covered by the payroll data, between the week ending 14 November and the week ending 28 November, the number of payroll jobs increased by 0.4 per cent, compared to an increase of 0.3 per cent over the previous fortnight.

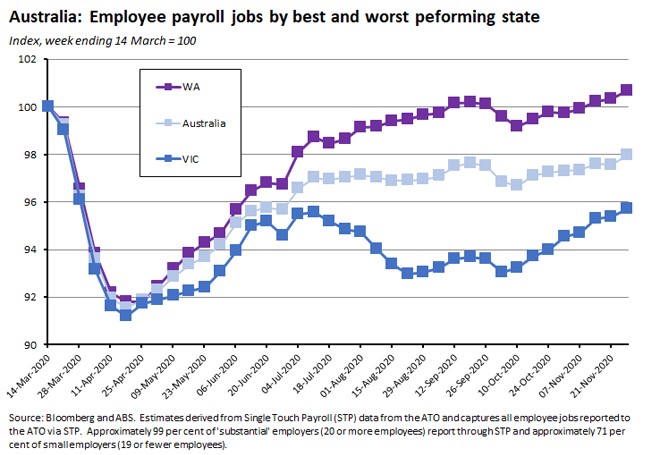

By state, since the week ending 14 March the largest cumulative fall in job numbers has been in Victoria, where payroll jobs were down by 4.3 per cent by the end of last month. The largest increase has been in Western Australia, where job numbers were up by 0.7 per cent over the same period.

Over the most recent fortnight of data between the week ending 14 November 2020 and the week ending 28 November 2020, job numbers were up 1.1 per cent in Tasmania, 0.6 per cent in New South Wales and 0.4 per cent in Victoria and Western Australia.

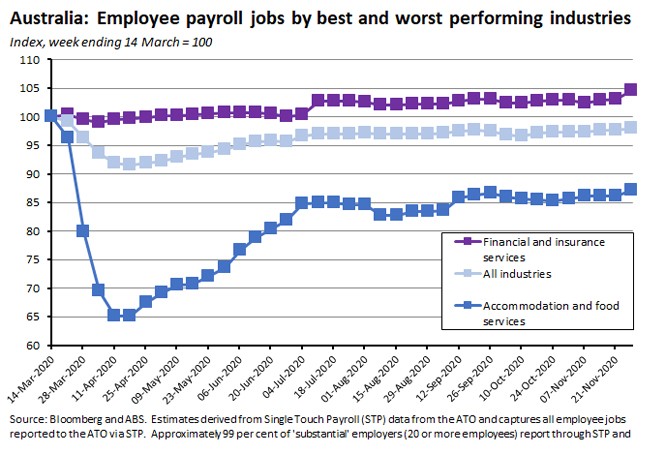

By industry, the biggest payroll job losses since March this year have been in accommodation and food services (down 12.8 per cent), in information media and telecommunications (down 11.6 per cent) and arts and recreation services (down nine per cent). Five industries have now added jobs over the period, with financial and insurance services adding the most.

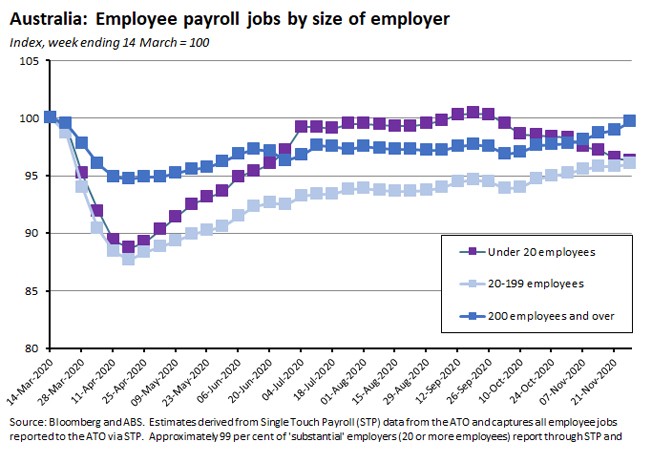

By size of business, job numbers at large firms (those with 200 employees or more) are now only about 0.3 per cent below their pre-pandemic levels, while job numbers at firms with less than 20 employees are 3.7 per cent down and jobs at firms with between 20 and 199 employees are four per cent down. In recent weeks, job numbers at large and medium-sized employers have increased, but job numbers at small employers have been falling.

Why it matters:

Payroll job numbers have been rising since mid-October, and as a result about 76 per cent of those jobs lost to mid-April this year had been restored by the end of last month.

The recovery in employment in Victoria has driven much of the recent increase: although nationally job numbers are still about two per cent below where they were in mid-March, the shortfall is 4.3 per cent in Victoria as opposed to about one per cent in the rest of Australia.

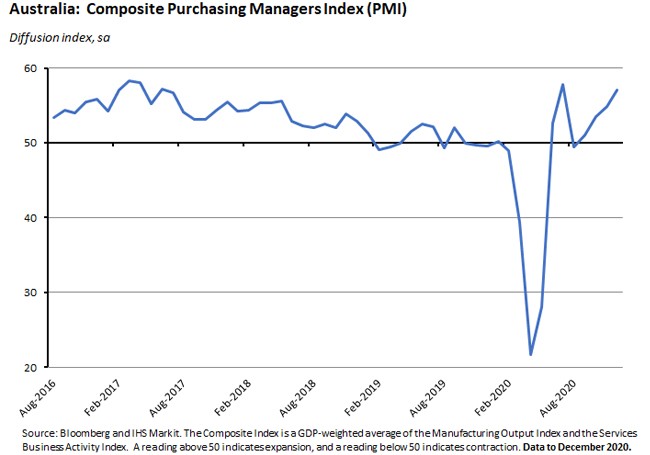

What happened:

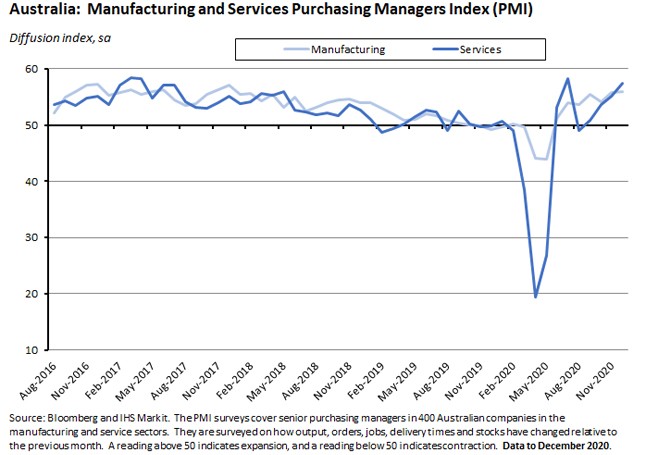

Preliminary ‘Flash’ PMI data from IHS Markit showed (pdf) the composite index rising to 57 in December from an index reading of 54.9 in November. Several subcomponents of the composite PMI also strengthened over the month, with the fastest upturn in new work intakes among private sector firms in close to three-and-a-half years, employment increasing for a second consecutive month and business confidence rising to its highest level since August 2018.

The ‘Flash’ Services Business Activity Index rose to 57.4 in December from 55.1 in November while the ‘Flash’ Manufacturing PMI edged higher to a reading of 56 from 55.8 the month before.

Why it matters:

The Composite PMI and the Services index both rose to five-month highs in December while the Manufacturing PMI hit a 36-month high, indicating that not only was Australia’s recovery in business activity sustained into December, but that the momentum behind that recovery has strengthened. Private sector activity is now growing at its fastest rate since July this year when the economy was enjoying its initial bounce back following the easing of the first round of COVID lockdowns.

What happened:

The RBA published the minutes from the 1 December Monetary Policy Meeting of the Reserve Bank Board. Members discussed a range of issues:

- On the international front, ‘members observed that the global outlook remained uncertain. Infection rates had risen sharply in Europe and the United States and the recoveries in these economies had lost momentum or even reversed. However, the news about vaccines had been positive, which should support the recovery of the global economy.’

- In terms of international trade, and in particular with regard to the deteriorating relationship with China, the discussion recognised that ‘the imposition by Chinese authorities of import bans and other obstacles to imports of some Australian products, particularly agricultural products and, more recently, coal, had also had an effect. However, it was also noted that Chinese demand for Australian iron ore exports remained firm.’

- In Australia, ‘the economic recovery was under way and recent data had generally been better than expected. Consumer spending had risen as restrictions were eased, business and consumer confidence had lifted, and housing markets had generally proved resilient. Employment had been recovering strongly and the peak in the unemployment rate was likely to be lower than the 8 per cent rate expected a month earlier. Nevertheless, the recovery was still expected to be uneven and protracted, and it remained dependent on significant policy support and favourable health outcomes.’

- Moreover, even with the economy doing better than expected, it would still ‘take some time for output to reach its pre-pandemic level and an extended period of high unemployment was in prospect. The high unemployment rate and excess capacity across the economy more broadly were expected to result in subdued wages growth and inflation over coming years. Given this environment, the Board viewed addressing the high rate of unemployment as an important national priority.’

Set against this backdrop, the policy implications were that ‘monetary and fiscal support will be required for some time.’ More specifically, the minutes noted that:

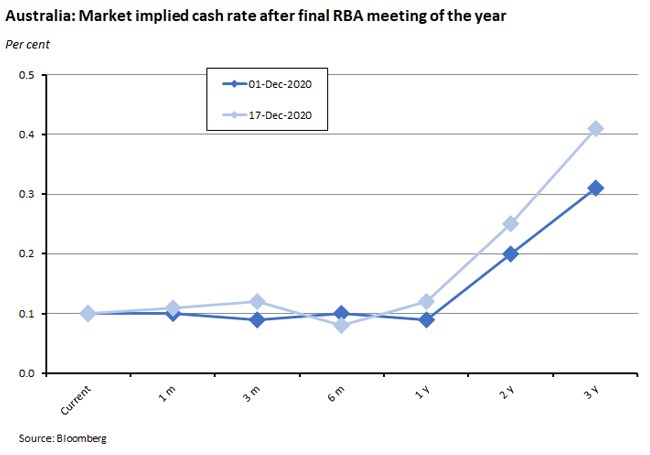

‘The Board remains committed to not increasing the cash rate until actual inflation is sustainably within the two to three per cent target range. For this to occur, wages growth would have to be materially higher than recent levels. This would require significant gains in employment and a return to a tight labour market. Given the outlook, the Board does not expect to increase the cash rate for at least three years. The Board remains of the view that it would be appropriate to remove the yield target before the cash rate itself were increased.’

Why it matters:

The minutes from the last RBA board meeting of 2020 depict a central bank cautiously pleased with the recent run of positive Australian data, but one which also continues to forecast a recovery that will be ‘uneven and protracted,’ marked by high unemployment, low wage growth and low inflation. As a result, the RBA is still sending the message that it expects the cash rate to remain at anchored at near-zero ‘for at least three years.’ Any future change to the cash rate will be preceded by the removal of the RBA’s yield curve control (YCC) target.

At the time of writing, the run of positive data that have followed the 1 December meeting (including a better than expected Q3 GDP result and strong readings on consumer and business confidence) have seen market sentiment running a little more positive than the central bank’s relatively cautious stance and that in turn has been reflected in a modest increase in market expectations regarding the future level of the cash rate. But the increase is a marginal one: at the three-year horizon, market pricing still implies that the cash rate will remain below 0.5 per cent.

The next RBA meeting is scheduled for 2 February, at which point the central bank will also have this month’s and the December labour market results to consider, along with the Q4 CPI reading and the fiscal update provided by the MYEFO.

What happened:

The ANZ Roy Morgan Weekly Index of Consumer Sentiment rose 1.7 per cent to an index reading of 111.2 for the weekend of 12-13 December.

Four of the five subindices increased over the week with the fifth unchanged from the previous week. The biggest gain was in ‘current financial conditions’ which jumped by 6.4 per cent, with the second strongest increase in ‘current economic conditions’ which rose by 2.9 per cent.

Why it matters:

A third consecutive weekly rise in confidence took the index up to a new high for 2020, with most subindices now either back to or above pre-pandemic levels. The exception is the ‘current financial conditions’ subindex which is still – just – in negative territory, even after the past week’s large gain. The overall index is now at its highest since Melbourne Cup weekend in 2019 (when it hit 113.5). After a tough year, households look to be ending 2020 in a more positive frame of mind.

What happened:

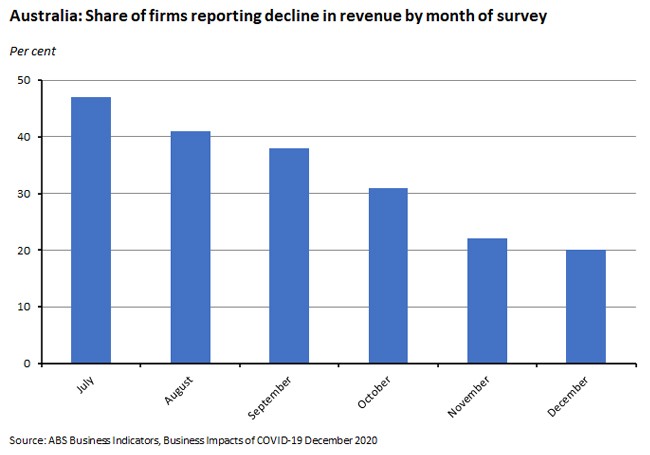

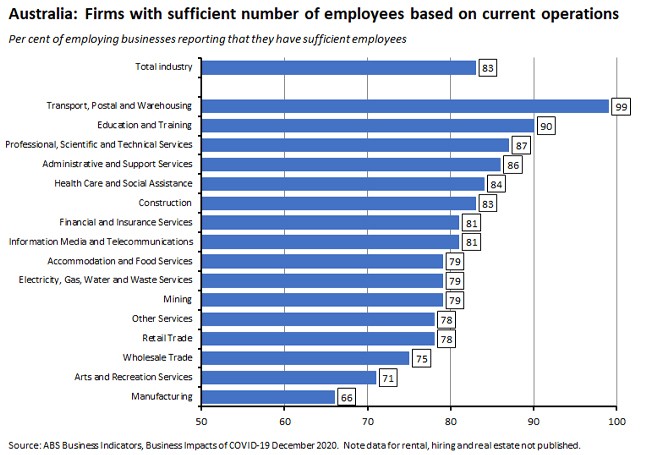

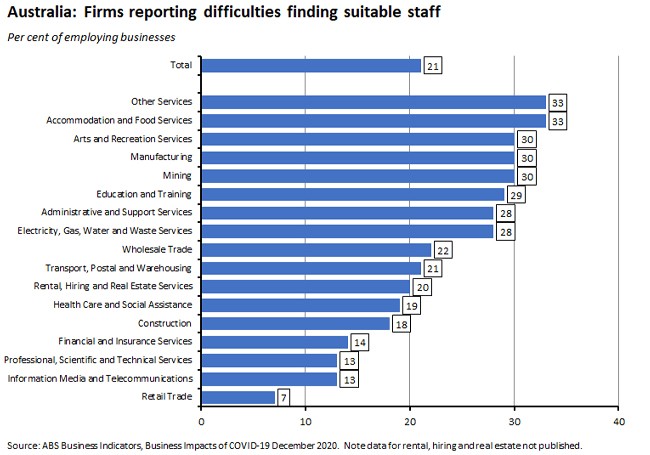

The December version of the regular ABS survey on the Business Impacts of COVID-19 was released. The headlines from this month’s findings were that 25 per cent of businesses reported increased revenue over the last month, 21 per cent of employing businesses said they were having difficulty finding suitably skilled or qualified staff and 65 per cent of medium and large employing businesses told the ABS that they plan to employ staff over the next three months.

The December survey showed the share of businesses reporting a fall in revenue fell to just 20 per cent, down from 45 per cent in the July survey.

About 83 per cent of businesses told the ABS that they currently had a sufficient number of employees based on their current operations, with this share ranging from 99 per cent in transport, postal and warehousing to 66 per cent in manufacturing.

At the same time, more than one in five businesses said that they were having difficulties in finding suitably qualified or skilled workers, with the shortages most acute in other services and accommodation and food services.

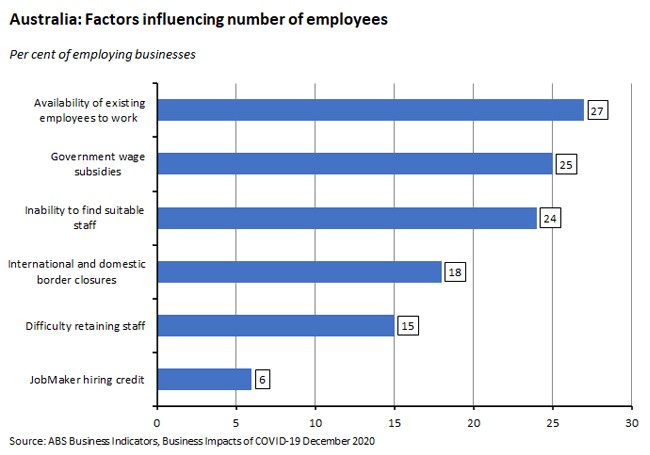

Businesses also reported on the factors that were influencing current employee numbers, with the most popular factor (cited by 27 per cent of respondents) the availability of existing employees to work.

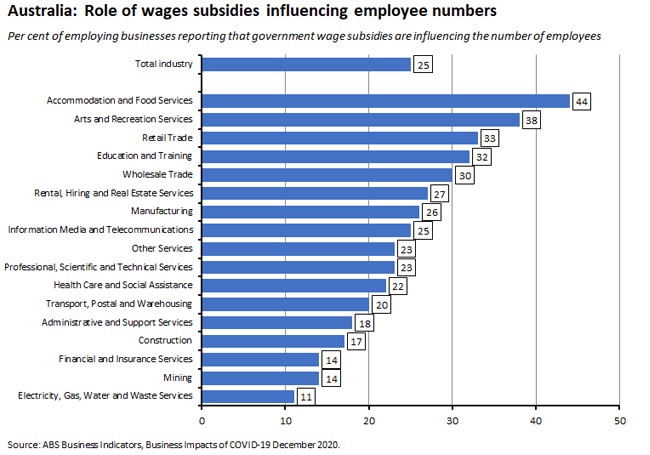

Government wage subsidies also continue to play an important role in employment outcomes, with 25 per cent of businesses saying they were an influence on current employee numbers, with this share rising to 44 per cent in the case of accommodation and food services and 38 per cent for arts and recreation services. The JobMaker hiring credit was also credited with an impact on employment by six per cent of respondents.

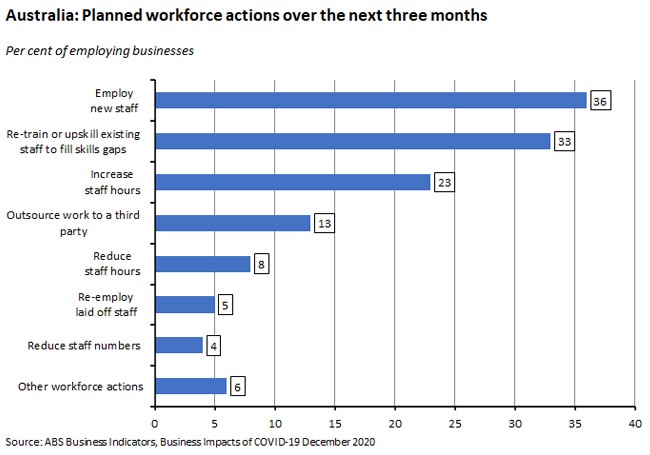

Finally, 36 per cent of employing businesses said they planned to recruit new staff over the next three months while 23 per cent planned to increase staff hours and five per cent planned to re-hire laid off workers, compared to eight per cent that planned to reduce hours and four per cent that intended to cut staff numbers.

Why it matters:

The ABS survey of businesses continues to paint an interesting picture of the differential impact of COVID-19 across industries and the impact of government business. Notable in this month’s survey was the ongoing importance of wage subsidies as an influence on employment, with one in four businesses citing them as a factor in determining the number of employees.

What I’ve been reading . . .

The latest ABS Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey highlights some of the behavioural changes produced by the pandemic in areas such as online shopping and telehealth. For example, one in three Australians told the Bureau that they now prefer to do more shopping online than before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. More people in Victoria (43 per cent) and New South Wales (35 per cent) preferred to shop more online than before the pandemic, when compared with people in the rest of Australia (26 per cent). The survey also said that 18 per cent of Australians reported using a Telehealth service in the previous four weeks, with 49 per cent of Australians saying that they were likely to use a Telehealth service beyond the COVID-19 restriction period. Finally, in terms of changes to behaviour made during the pandemic that Australians would like to see persist post-COVID, respondents nominated: spending more time with family and friends (37 per cent); spending more time outdoors (32 per cent); spending less and saving more (32 per cent); less environmental impact (30 per cent); working from home (30 per cent); a slower pace of life (30 per cent) and taking more domestic holidays (30 per cent).

Also from the ABS, last Friday the Bureau released the latest statistics from Characteristics of Employment. Some of the findings include: (1) Median employee earnings as of August 2020 were $1,150 per week, up $50 (4.5 per cent) from Aug 2019 while median hourly earnings were $36/hour, up $3.50/hour (10.8 per cent) since August 2019. The ABS points to significant changes in the distribution of earnings in August 2020, with 920,000 employees earning between $700 and $799 per week, much higher than the 580,000 earning the same amount in August 2019. Most of this increase was from workers who earned $750 per week, and therefore likely captured employees receiving the then $1,500 per fortnight JobKeeper supplement; (2) There were 2.3 million casual employees or 22 per cent of employees in August 2020 down from 2.6 million or 24 per cent in February 2020 (the ABS defines a ‘casual’ worker as an employee with no entitlements to paid leave). The pandemic took a particularly heavy toll on the number of casual employees earlier in the year but there has since been some recovery in numbers; (3) There were one million independent contractors (8.2 per cent of employment) in August 2020. Between August 2019 and August 2020, the number of people working as full-time independent contractors fell 9.4 per cent, from 670,000 to 610,000. In contrast, employees working on a fixed-term contract increased 6.1 per cent, from 390,000 to 410,000. (4) Some 14.3 per cent of employees were trade union members in August 2020, down from 14.6 per cent in 2018 and from 40 per cent back in 1992.

Treasury has published Australia’s first population statement. Key insights include: (1) Australia’s population is estimated to be around four per cent smaller (1.1 million fewer people) by 30 June 2031 than it would have been in the absence of COVID-19; (2) Reduced net overseas migration and fewer births will skew the population older; (3) Australia’s population is expected to reach 28 million during 2028–29, three years later than estimated in the absence of COVID-19; (4) Melbourne is projected to overtake Sydney to become Australia’s largest city in 2026–27, with a population of 6.2 million by 2030–31, compared to six million in Sydney.

Deloitte Access Economics’ (pre-MYEFO) take on the outlook for the Federal Budget. Underpinning the fiscal outlook is what Deloitte describes as a ‘story of economic outperformance versus the official forecasts’ presented in Budget 2020-21. In particular, Deloitte reckons that the Australian economy will be larger than Treasury projected by $33 billion in 2020-21 alone, a gap that widens to $106 billion by 2023-24. That in turn should push spending down (fewer Australians on JobKeeper and JobSeeker) and revenues up (higher corporate profits and personal incomes).

The RBA’s Jonathan Kearns, Head of Financial Stability, gave a speech on Banking and the COVID-19 Pandemic. Kearns noted the resilience of the banking system in the face of the virus, pointing out that it has been able to cushion the economic shock by continuing to support households and businesses and crediting both ‘the wholesale reform of bank regulations that followed the GFC’ as well as ‘the unprecedented policy actions taken this year by central banks and fiscal authorities.’ He also reviewed the resilience of banks to downside scenarios on growth and unemployment, and the impact of low interest rates.

The Grattan Institute’s Annual Wonks’ List.

The draft version of CSIRO’s latest GenCost report is now available for review. It finds that ‘solar photovoltaics (PV) and wind continue to be the cheapest new sources of electricity’ and that ‘Solar PV and batteries are projected to continue experiencing the fastest cost reductions of any source of energy technology.’ See also this piece which examines the role of storage and other integration costs.

Hugh White on why Australia is the perfect target for China.

An IMF blog post on What to do When Low-for-Long Interest Rates are Lower and for Longer.

Despite my scepticism about our ability to predict even one year ahead, let alone longer, I still can’t resist projections about where we might be heading. So, here is a selection from FT and Nikkei journalists on what various aspects of the world might look like in 2025 (the rise of AI-driven finance, the approach of peak oil demand, consumers that are both more cautious and more online) and here is Martin Wolf with five forces that will define the post-COVID future (technology, inequality, indebtedness, deglobalisation and political tensions).

New data on the global trade policy response to the pandemic.

The CFR looks back at how 2020 has shaped the most important bilateral relationship on the planet.

The WSJ’s Greg Ip examines the evolving economics of ‘lockdown lite.’

Looking at developing economies, Barry Eichengreen writes on the ‘debt dogs’ that failed to bark during the pandemic and argues that ‘it’s hard to know whether to be reassured or alarmed by the silence.’

The Economist magazine examines the risks around a resumption in inflation. ‘Inflationistas’ worry about the combined impact of the after-effects of government stimulus measures, demographic shifts and changes in policymakers’ attitudes to the economy could trigger a return to high inflation. The piece is cautiously sceptical, concluding that the chances are that the recovery will not be marked by excessive inflation, although also conceding that this is not guaranteed.

Selected books I’ve read this year (Economics and related) . . .

Most of my economics reading this year has been short form (essays, columns, articles, papers and so on) but I have managed a few books too. The pick of the bunch would be:

The Economics of Belonging: A Radical Plan to Win Back the Left Behind and Achieve Prosperity for All. By Martin Sandbu. Sandbu writes the excellent Free Lunch columns in the FT and this is a book-length exploration of some of the themes covered there, with a focus on policies designed to help the so-called left behind. Covers current debates on tax, macro policies, minimum wages, and a UBI.

Angrynomics. By Eric Lonergan and Mark Blyth. Presented as a dialogue between the two authors, this is an examination of some of the forces driving populism. But more interestingly, it also offers a set of policy proposals including making the case for a national wealth fund and a data dividend.

The Economists Hour: How the false prophets of free markets fractured our society. By Binyamin Applebaum. I reviewed this one back in August, noting that it ‘tells a compelling story of how the economics profession, particularly in the United States, changed its mind about a whole range of issues and in the process helped deliver an economic policy revolution.’ Although as the subtitle indicates, this is not a particularly sympathetic take on either that revolution or on the role of economists.

Radical Uncertainty: Decision-making for an unknowable future. By Mervyn King and John Kay. Again, I reviewed this one earlier this year, saying it was ‘an interesting and wide-ranging read and covers a huge amount of ground’ although I also thought it was ‘almost certainly too wide-ranging: the central argument sometimes all but disappears in the sheer amount of terrain that’s traversed here.’ On reflection, maybe that latter judgment was a little harsh.

The Case for People's Quantitative Easing. By Frances Coppola. Now that the RBA has joined the shift to QE, Coppola’s argument – that we could do better than conventional QE by targeting households directly – no longer appears quite as radical as it once did.

The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and How to Build a Better Economy. By Stephanie Kelton. In fact, I’ve just started this one (thanks Secret Santa!), so it will also be part of my summer reading list (below) and as I’m only a few pages in, it’s probably too soon to judge quality. Still, radical policy choices and a surge in fiscal support have helped make the debate around MMT a recurring theme this year, and although I’ve read and linked to plenty of writings in short form on the topic, I feel a little guilty at only getting around to Kelton’s book on MMT now. But better late than never.

. . . and some fiction…

On the fiction front, I’ve enjoyed Agency by William Gibson; The Glass Hotel by Emily St John Mandel; Piranesi by Susanna Clarke; Utopia Avenue by David Mitchell; Devolution by Max Brooks; and Two tribes by Chris Beckett.

. . . and my Summer reading (wish) list

This is pretty aspirational at the start of the summer break, but as well as completing the Kelton book noted above, I hope to have read at least a couple of the following by the time I’m back in the office next year:

Putin’s People

The Price of Peace: Money, Democracy, and the Life of John Maynard Keynes

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content