Overview

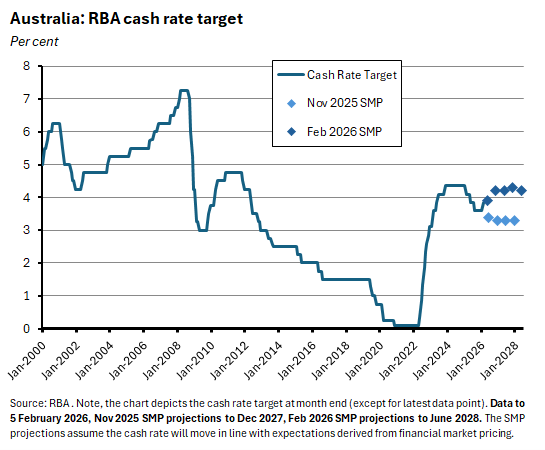

- The Monetary Policy Board (MPB) voted unanimously this week to lift the cash rate target by 25bp to 3.85 per cent. The MPB was responding to stronger than expected inflation outcomes and a judgement that the economy was running intocapacity constraints.

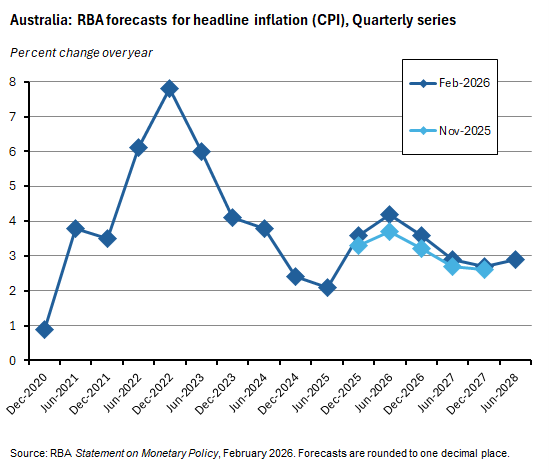

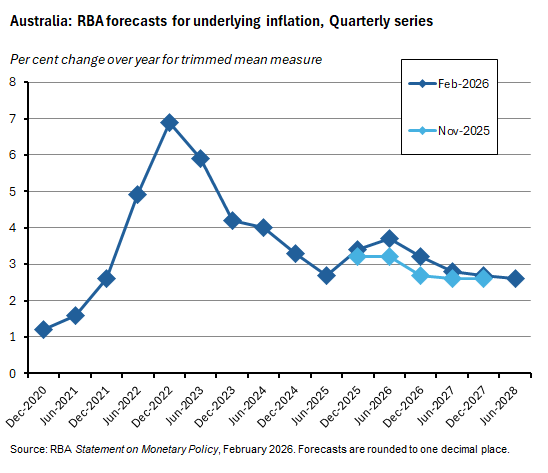

- The RBA now forecasts that inflation will stay higher for longer, with both headline and underlying measures projected to remain above the RBA’s target band until 2027 and above the midpoint of that band into 2028, even assuming at least two further rate hikes.

- It follows that further policy tightening is likely, although the RBA will maintain its cautious, data-dependent approach.

- If Australia’s economic speed limit has now fallen such that real GDP growth of around two per cent is the maximum the economy can sustain without overheating, this has negative implications for living standards, fiscal sustainability and more.

This week, we examine the Monetary Policy Board’s decision to deliver a 25bp hike in the cash rate target, review new forecasts in the RBA’s latest Statement on Monetary Policy and consider the implications for future interest rate moves, growth, central bank credibility, and more.

At its meeting this week, the Monetary Policy Board (MPB) voted unanimously to increase the cash rate target by 25bp to 3.85 per cent. The move was widely anticipated, with market pricing beforehand suggesting a greater than 70 per cent probability of the Board voting to hike. Moreover, set out in last week’s note, December’s uncomfortably high inflation reading left the centralbank with little choice but to tighten.

According to the accompanying policy statement,

‘A wide range of data over recent months have confirmed that inflationary pressures picked up materially in the second half of 2025. While part of the pick-up in inflation is assessed to reflect temporary factors, it is evident that private demand is growing more quickly than expected, capacity pressures are greater than previously assessed and labour market conditions are a little tight.

The Board judged that inflation is likely to remain above target for some time and it was appropriate to increase the cash rate target.’

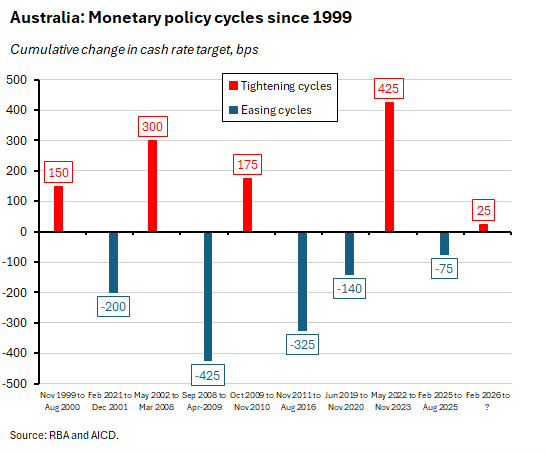

It’s the first change in the cash rate target since August 2025’s 25bp rate cut and the first increase since November 2023’s 25bp hike. It returns the policy rate to its pre-13 August 2025 level and means that last year’s easing cycle has proven to be both short and shallow at just three 25bp cuts in total, one of which has already been reversed.

What went wrong?

So, why did the previous easing cycle prove to be so brief and what prompted the MPB to tap on the policy brakes via a 25bp rate hike?

The RBA was moved to act largely because both domestic and international activity turned out to be stronger than the RBA had previously expected, while inflation outcomes also surprised to the upside. As indicated in the previous quote, the RBA thinks some – although not all – of that inflation surprise is evidence of capacity constraints in the economy.

The immediate trigger for this week’s rate hike, then, was the latest set of inflation readings, which reported both headline - and more importantly - underlying inflation rates running above the top of the RBA’s two-three per cent target band, above the RBA’s forecasts as set out in the November 2025 Statement on Monetary Policy (SMP), and well above the midpoint inflation target of 2.5 per cent.

According to updated forecasts presented in the February 2026 SMP, the RBA now thinks both headline and underlying inflation will be higher for longer (see charts).

Granted, a large share of that rise in inflation likely reflects temporary factors, with the SMP citing sector-specific demand effects impacting new dwelling and durable goods prices, alongside price volatility in the case of fuel and overseas prices. But the central bank accepts that the broad-based nature of the December inflationnumbers indicate that economy-wide capacity pressures were also at work.

Sitting behind the RBA’s upgraded inflation projections, then, are five further factors:

- Growth in private demand proved to be surprisingly strong in the second half of last year. Although annual real GDP growth of 2.1 per cent in the September quarter 2025 was around the RBA’s estimate of potential growth, activity looks to have accelerated further in the December quarter thanks to stronger-than-expected increases in household consumption, dwelling investment and business investment.

- At the same time, labour market conditions remained tight (see, for example, our look at the December labour market results), as reflected in a low unemployment rate and strong growth in unit labour costs.

- In the RBA’s view, the economy is now running up against its speed limit. According to the SMP, the central bank judges that capacity pressures in the Australian economy are now greater than it had previously expected. By the end of 2025, the output gap (the difference between aggregate demand and the supply capacity of the economy to meet that demand) was not only positive, but was also wider than the November 2025 SMP had anticipated.

- Global economic conditions had not provided any significant offset to this domestic strength, with global economic activity in the second half of last year also proving more resilient than had been anticipated (see also here the extended discussion on forecasting lessons from 2025 from our note two weeks’ back). Here, the SMP’s conclusion is that the ‘recent escalation in geopolitical tensions has had a limited economic effect on Australia and its trading partners to date.’

- Finally, the RBA also thinks domestic financial conditions in the economy have been easier than it previously assessed. The February 2026 SMP points to lower lending rates, a rise in total credit growth, an uptick in the ratio of household credit to income, an increase in the ratio of business debt to GDP and low risk premia as all supporting this judgement. Further, according to some model estimates, the cash rate has now fallen below the neutral rate (although other measures still suggest it remains above neutral). As a result, there is now considerable uncertainty as to whether financial conditions remain restrictive overall.

New outlook: Inflation up, growth down

As already noted, the new SMP forecasts have inflation higher for longer. In the near term, both headline and underlying inflation are now expected to diverge further from target by the middle of this year and then remain above target through year-end. Inflation is only projected to have a ‘two’ in front of it again by 2027. And even by mid-2028, both headline and underlying inflation are predicted remain (just) above the 2.5 per cent midpoint of the target band.

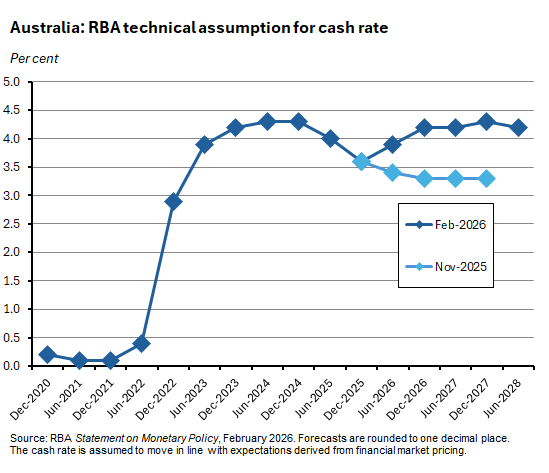

These projections are based on the technical assumption that the cash rate will move in line with market expectations, which assumes at least two additional rate hikes over the forecast horizon.

The new forecasts also assume a stronger exchange rate, with the Trade Weighted Index now assumed to be 64.3 across the forecast period, compared to 61.4 in the November 2025 SMP.

This forecast tightening in financial conditions is also set to take a toll on expected growth and employment outcomes. For example, real GDP growth is now forecast to slow to 1.8 per cent by the end of this year and then ease to 1.6 per cent through 2027. Back in November, growth was expected to remain closer to two per cent. Likewise, the unemployment rate is now expected to rise to 4.6 per cent by the end of the forecast period, exceeding the previous peak of 4.4 per cent.

Three judgments, three risks

As usual, the SMP provides a helpful summary of the three key judgments that underpin the SMP and its forecasts, as well as the three key risks to that outlook.

First the three judgments:

- There is more strength in Australian private demand than the RBA had expected.

- The unexpected strength in inflation in the second half of last year is mainly a temporary story but also reflects greater and more persistent economy-wide capacity pressures than the RBA had anticipated.

- Financial conditions are now expected to become modestly restrictive under the SMP’s assumptions regarding the trajectory of the cash rate from here.

Three associated risks:

- The RBA’s central scenario may place too much weight on the role of temporary factors in driving recent inflation outcomes.

- The balance between demand and supply may turn out differently than the RBA expects, with risks to both sides (for example, growth in demand could turn out to be either stronger or weaker than forecast).

- Risks to global activity remain tilted to the downside, whereas risks to the global inflation outlook may have started to shift to the upside.

‘One and done’ looks unlikely

The MPB’s initial response has involved one 25bp tap on monetary policy brakes (in response to a direct question, the governor told the post-meeting press conference that the MPB had not considered a larger 50bp rate hike). But does this 25bp hike mark the start of a new monetary policy tightening cycle? When she was asked this question, Governor Bullock was non-committal:

‘I would say I don’t know if it’s in a cycle. Certainly, it’s an adjustment…the Board is going to be actively monitoring. I can’t say one way or the other now. I don’t want to rule out, and I don’t want to rule in…We’re in this period where it’s not clear one way or the other.’

That lack of clarity, if sustained, implies that the MPB will remain data-dependent and cautious in its approach. The Board does not think it has fallen significantly behind the curve and it must now scramble to catch up. But caution is different from ‘one and done.’

As noted above, market pricing that underpins the new forecasts in the February SMP assumes at least two more rate hikes to come. And according to those same forecasts, that would still leave inflation at 2.6 per cent by mid-2028, above the desired mid-point of the target band.

In that context, and based on its current assessment of economic conditions, the Board is likely to decide to tighten further from here. The next MPB meeting is due on 16-17 March, and the one after that comes on 4 - 5 May. At the time of writing, markets were expecting another rate hike at the May meeting and, for now at least, that looks like a plausible outcome.

Four other implications of the rate hike

There are at least four other issues raised by this week’s interest rate decision.

First, there is the impact on the RBA’s credibility. After just three rate cuts, the central bank has had to change direction and is now delivering what could well turn out to be the opening rate hike of a policy tightening cycle. That raises the question of whether this is the product of an earlier policy mistake by Martin Place, and if that mistake is damaging to central bank credibility.

In my view, this judgment overdoes things. In a data-dependent world, assessments are going to shift with the data. Given the elevated level of uncertainty that characterised the post-pandemic economic environment, it was always reasonable to expect that the data would throw up various surprises, and that therefore a degree of flexibility in the policy response would be required.

Still, those arguing at the time that Australia’s central bank was too hasty to ease policy will now be feeling vindicated.

The second issue concerns the unwelcome message we have just received regarding the economy’s new, lower speed limit. If the RBA’s assessment is correct and two per cent real GDP growth or less is the best that Australia can sustain without succumbing to overheating, that has important consequences for living standards, for fiscal sustainability, for corporate strategy and investment plans and more. It also boosts pressure on the government to advance the productivity agenda to help lift that speed limit.

Third, as well as telling us something important about present supply side failings of the Australian economy, there could also be a message here about the post-pandemic environment more broadly. The period between the global financial crisis and COVID-19 was characterised by ‘low for long’ inflation and interest rates. After the pandemic and the great post-pandemic inflation surge, there was speculation among economists that structural changes in the global economy – demographic shifts, geoeconomic fragmentation, mounting public debt burdens, stretched supply chains, the impacts of climate change and the costs of the energy transition – could contribute to higher and more volatile inflation going forward. If so, that could produce a world of sharper and shorter monetary policy cycles that would look more like this recent experience, than the longer cycles that characterised the pre-pandemic environment.

Finally, there is the relationship between fiscal and monetary policy. In the aftermath of this week’s rate hike, not all blame was directed at the central bank. Some was targeted at the government in the form of the claim that excessive government spending was unduly complicating the task of monetary policy.

Rather than wading into that debate, however, let us consider a potentially more interesting question. If we did want fiscal policy to take a more active role in helping to tame inflation, what might that look like? Some of the standard arguments against relying on fiscal policy to ‘do’ short-term macro stabilisation rest on claims around timeliness. (It will take a government much longer to alter tax policies or shift spending priorities than it will for a central bank to change interest rates, for example).

Others cite political economy constraints (politically it will always be easier for governments to implement stimulative policies – cut taxes/increase spending – than to conduct contractionary measures, creating a systemic bias in their policy reaction function. This is a key justification for outsourcing stabilisation policy to independent central banks). Hence, rather than direct government intervention, the macro stabilisation impact of fiscal policy often relies on the operation of the so-called automatic stabilisers. For example, when the economy is expanding, the tax take will tend to increase and spending on unemployment will tend to fall, even absent any policy change, so taking a bit of steam out of the system without the need for any policy intervention.

It follows that, if we would like fiscal policy to play a more active role in dealing with inflation, one option we might want to consider would be to increase the automatic role of fiscal stabilisers in the economy. For example, on the spending side of the ledger, governments could link the generosity and/or duration of unemployment benefits to the state of the economic cycle via an economic rule or indicator approach. Likewise, on the revenue side, governments could try to tie tax collection more closely to the cycle. For example, a variable GST rate that falls during a recession and rises during a boom could have a similar effect to changes in interest rates (although note that an inflation targeting central bank would need to look through any subsequent GST-led changes in headline inflation). Alternatively, the more progressive the tax system, the greater the role it could play in economic stabilisation.

True, seeking to use fiscal policy in this way comes with important drawbacks attached and raises issues around policy trade-offs. Even so, given all the sound and fury of this week’s debate around the impact of fiscal policy settings on inflation, discussion of the merits of these kinds of fiscal anti-inflation policies has been noticeable mainly by its absence.

Other Australian data points to note

According to the Cotality Home Value Index, Australian home values rose by 0.8 per cent over the month in January 2026 to be up 9.4 per cent over the year. The combined capitals index rose 0.7 per cent month-on-month and 9.2 per cent year-on-year. Every capital city recorded an increase in home values last month, although Sydney and Melbourne values remain below their earlier peaks.

Last month’s rise in values came despite ongoing pressures on affordability and mounting serviceability constraints, with higher interest rates and slowing population growth now set to add further to market headwinds. Pushing in the other direction, however, is a price-boosting interaction between above average housing demand and sustained low housing inventory (the number of homes advertised for sale last month was 25 per cent below the five-year average for this time of year). Meanwhile, the national rental vacancy rate was 1.7 per cent in January 2026. That was up a bit from the record low of 1.5 per cent recorded last September but still well below the long run average vacancy rate of 2.5 per cent. Low vacancy rates continue to drive rental growth, with rents recording their strongest monthly growth since April 2025. Over the past five years, weekly rents have jumped by 42.4 per cent, compared to growth of just 8.2 per cent over the previous five-year period.

The ABS said the total number of dwellings approved fell 14.9 per cent over the month (seasonally adjusted) to 15,542 in December 2025. That was just 0.4 per cent above approvals in December 2024. Approvals for private sector houses were higher over the month (up 0.4 per cent) and over the year (up 5.7 per cent), but approvals for private sector dwellings excluding houses slumped 29.8 per cent over the month to be down 6.1 per cent from the previous year. Note that this monthly drop followed an outsized 29.6 per cent month increase in November 2025, reflecting the volatility of the apartment approvals series.

In another recent sign of labour market strength, ANZ-Indeed Job Ads rose 4.4 per cent month-on-month in February 2026, marking the strongest monthly gain since February 2022. That said, in annual terms Job Ads were still down 3.2 per cent.

The ABS has published December quarter 2025 estimates for its Selected Living Cost Indexes (LCIs). In annual terms, increases ranged from a low of 2.3 per cent for the Employee LCI to a high of 4.2 per cent for the Age pensioner LCI. Relatively subdued growth in living costs for employee households reflects the impact of falling mortgage interest rate charges. According to the Bureau, they fell 6.4 per cent over the year due to a cumulative 75bp of RBA policy easing through to August 2025. In contrast, the largest annual increases in LCIs were recorded by households with government payments as their main income source, as those groups saw a relatively larger impact on their electricity costs from the exhaustion of State Government electricity rebates in Queensland and Western Australia.

The ABS report on Barriers and Incentives to Labour Force Participation estimates that as at the September quarter 2025, there were 3.2 million people (aged 18 to 75) without a paid job, of which 1.2 million people wanted a job and two million did not. There were also 1.9 million people who were retired or permanently unable to work. That left 14 million people either currently employed or with a job to start or return to.

Australia’s goods trade balance recorded a $3.4 billion surplus in December last year, up $0.8 billion on the November 2025 outcome.

Further reading and listening

- The February 2026 RBA chart pack.

- Some reaction to this week’s rate hike from Richard Holden and John Kehoe in the AFR

- Grattan looks at who funded campaigns for the 2025 federal election.

- A Productivity Commission submission reckons Australia’s current approach to WFH ‘appears to have arrived at a sensible middle ground.’

- From the Lowy Interpreter, some Panamanian lessons for Australia.

- The Chair of the US Federal Reserve is one of the most important actors in the global economy. President Trump has nominated Kevin Warsh to serve as the next chair. If confirmed by the Senate, Warsh will take over the role when Jerome Powell’s term expires in mid-May this year. The WSJ has a backgrounder on Warsh’s long road to the Fed chair while both the Journal and the FT have stories on how Warsh secured Trump’s favour in the recent popularity contest for monetary policy chiefs. This FT piece considers whether Warsh will oversee an overhaul of the Fed, the Economist magazine’s Free Exchange column notes that the nominee was an inflation hawk until he wasn’t, and this WSJ article explains why Wall Street isn’t sure quite what its getting. There are also columns from the FT’s Martin Wolf (‘Warsh is a better candidate than many of the others on the list. But he is a confusing, perhaps confused, figure’) and the WSJ’s Grep Ip (‘Many on Wall Street suspect Warsh said what was needed to get the job, and after a suitable interval in office, will be his own man.’)

- On the difficulties of leveraging Europe’s US$12.6 trillion holdings of US assets.

- And how different climate policies affect carbon leakage through trade.

- The United States is flirting with its first-ever population decline.

- On China’s century of purges.

- Perry Mehrling reviews Ken Rogoff via Charles Kindleberger.

- More on the Warsh appointment from the FT’s Unhedged podcast and a critical take from Odd Lots.

- Ezra Klein talks to Adam Tooze on how the world sees America.

- Tyler Cowen in conversation with Andrew Ross Sorkin on market bubbles and the lessons of the 1929 crash.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content