This week we look at the implications of the latest wage data from the ABS and review the Minutes from the November meeting of the RBA’s Monetary Policy Board (MPB).

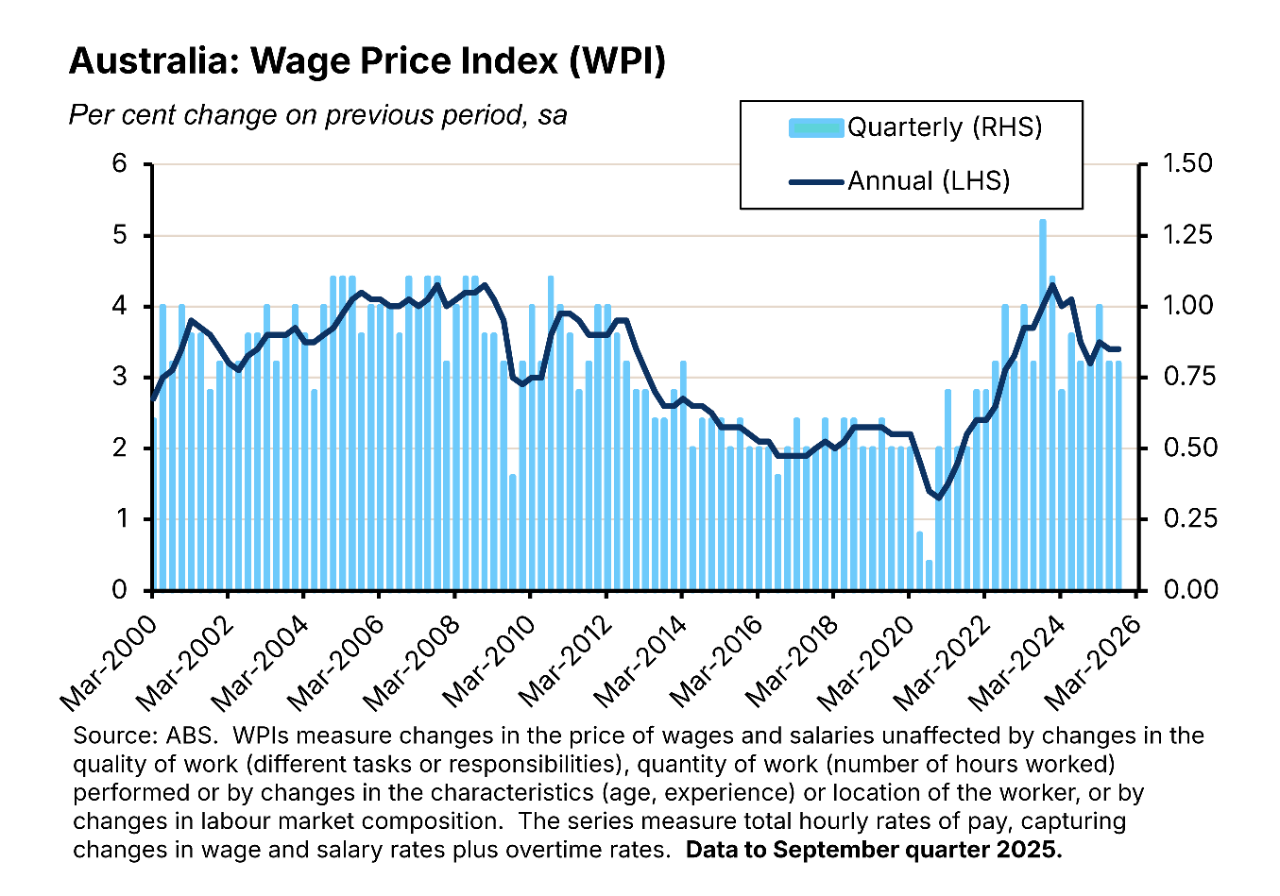

Australian wage growth as measured by the Wage Price Index (WPI) was 3.4 per cent over the year in the September quarter 2025. Mostly, that was an unremarkable result. The rate of growth was unchanged from the previous quarter, was in line with market expectations, and was broadly consistent with the latest set of RBA projections. Still, there are three broad messages we can take from the numbers:

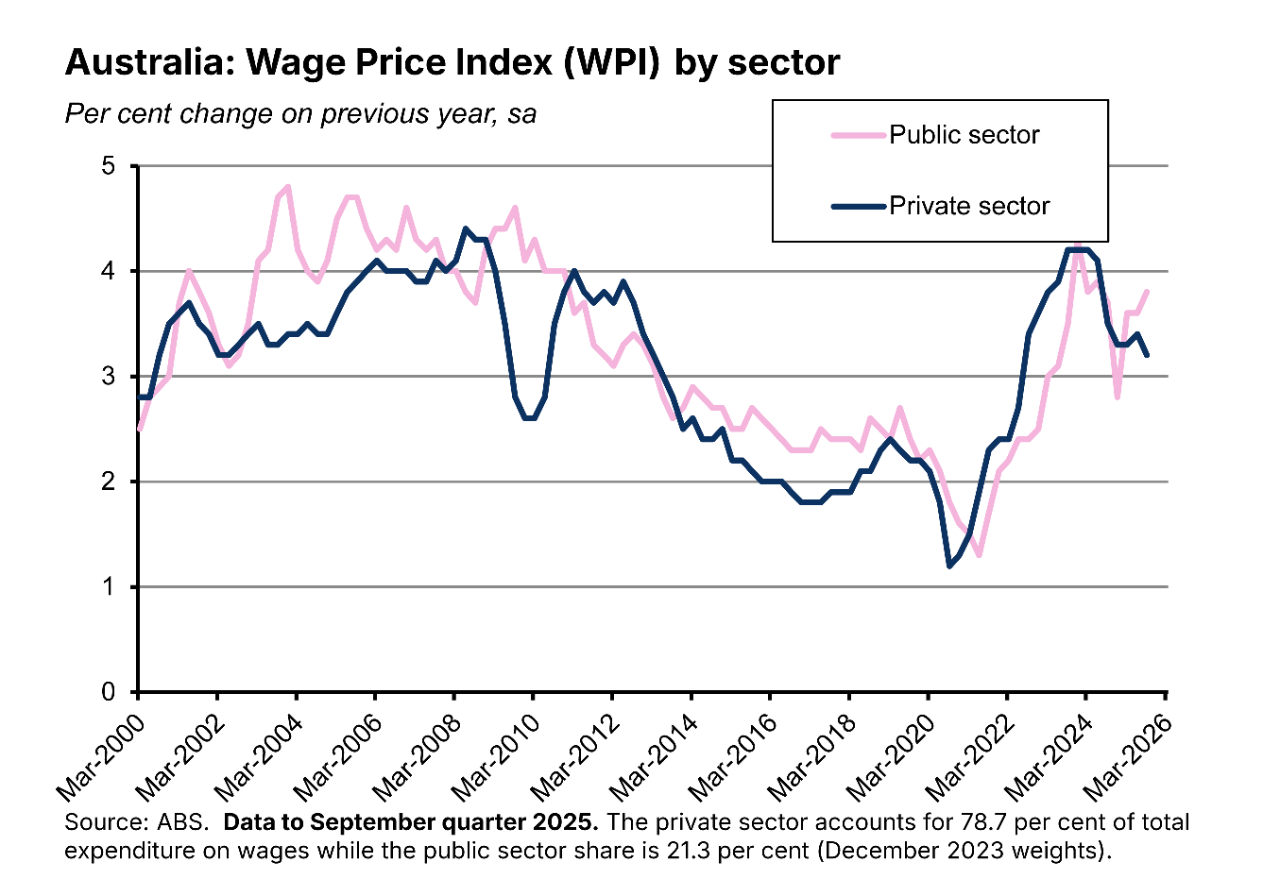

- Another strong result for public sector wages supported overall wage growth last quarter. Look only at the private sector, however, and wage growth eased modestly, slowing from 3.4 per cent to 3.2 per cent. Likewise, growth in wages negotiated under individual arrangements also moderated a little, edging down from 3.1 per cent to three per cent. That suggests a slight loosening in conditions in those areas where wages are relatively more subject to market pressure.

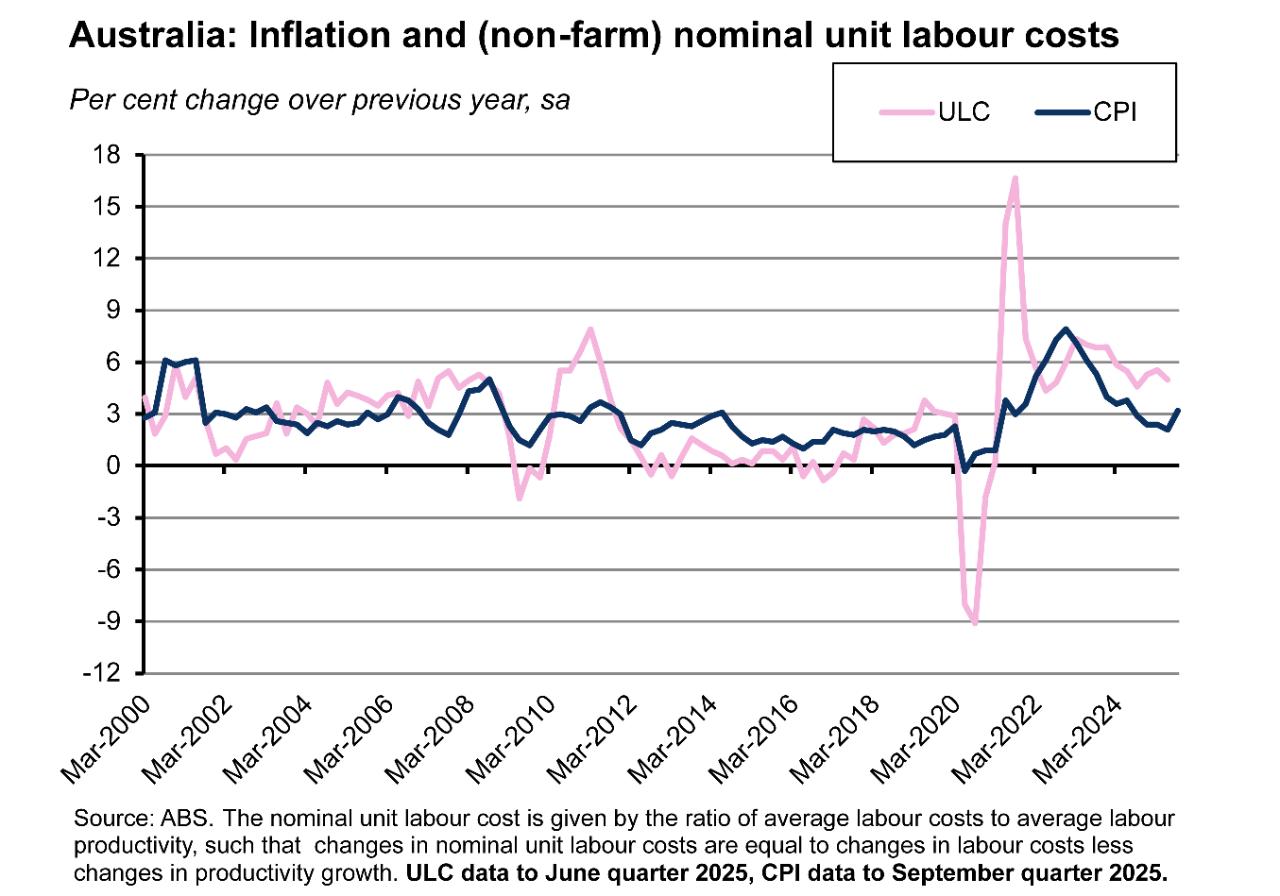

- Even so, the mismatch between overall wage and productivity growth persists, implying ongoing upward pressure on unit labour costs and therefore a continuing risk to the inflation outlook.

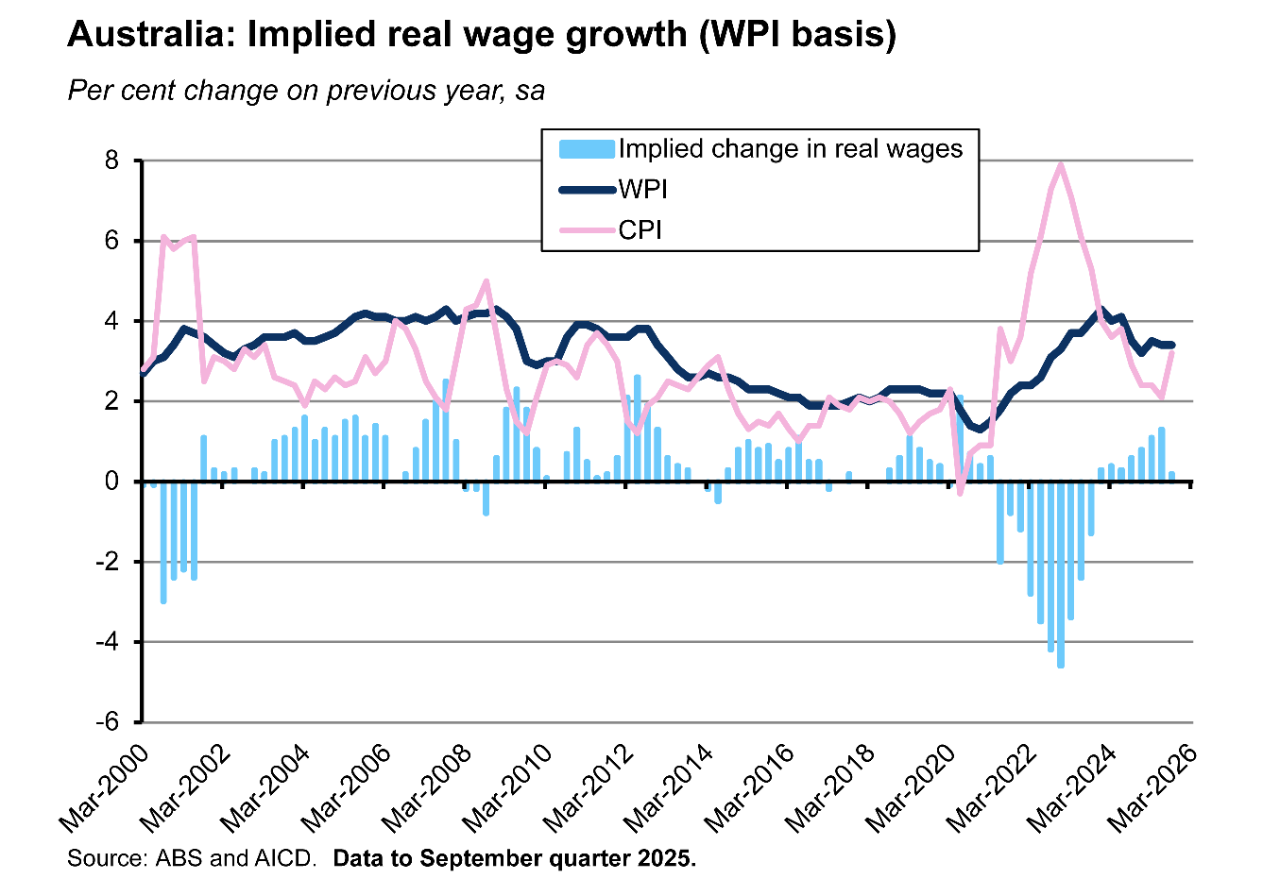

- Despite the uptick in inflation in the September quarter, real wage growth remained positive in year-on-year terms, if only just. But real wages are yet to return to their pre-pandemic level.

Turning to the RBA Minutes, the story here is mostly a recap of the thinking behind the MPB’s decision to leave the cash rate target unchanged earlier this month. Beyond that, a summary of the discussion around the outlook for inflation referenced an ‘alternative staff projection’ to the one included in November’s Statement on Monetary Policy (SMP). The latter assumed a further 30bp of rate cuts and sees underlying inflation in the top half of the target band across the forecast period. The alternative projections assume no further rate cuts which is enough to have inflation returning to the middle of the target band. That has encouraged some RBA-watchers to further increase the probability that the RBA’s policy easing cycle is now done, although with the MPB also reported to have considered scenarios for both holding and cutting (but not hiking) rates during its discussions, a Martin Place that remains in data-driven mode is still keeping its options open.

More detail on the wage numbers and the RBA Minutes below, along with a short roundup of other data releases and some suggestions for further reading and listening.

Wage growth held steady in the September quarter

The ABS said that the Wage Price Index (WPI) rose 0.8 per cent over the September quarter 2025 (seasonally adjusted) to be up 3.4 per cent over the year. Both quarterly and annual rates of growth were unchanged from the June quarter, and both were in line with market consensus forecasts. The numbers also look consistent with the RBA’s forecasts released earlier this month which projected annual WPI growth in the December quarter to run at 3.4 per cent before easing to three per cent across the remainder of the forecast horizon.

The September quarter WPI includes the impact of the recent Fair Work Commission Annual Wage Review, which had awarded a 3.5 per cent increase. By method of pay setting, the annual rate of wage growth last quarter was four per cent for Enterprise Agreements, 3.5 per cent for Awards and three per cent for Individual Arrangements.

The public sector led wage growth in Q3:2025, with the Public Sector WPI up 0.9 per cent quarter-on-quarter and 3.8 per cent year-on-year. According to the ABS, state government pay rises contributed 82 per cent of public sector wage growth, reflecting the implementation of several state-based enterprise agreements after extended bargaining periods. Public sector wage growth has now outpaced the private sector for three consecutive quarters.

In contrast, the pace of private sector wage growth eased to 0.7 per cent quarter-on-quarter and 3.2 per cent year-on-year. For those private sector jobs that recorded a change in wages the average hourly increase was 3.6 per cent – the lowest increase since the March quarter 2022.

Implications for unit labour costs and inflation

As we’ve explained before, the RBA likes to keep an eye on the rate of growth in unit labour costs (ULCs) as one indicator of inflationary pressure in the economy. Growth in ULCs is equal to the difference between growth in nominal labour costs (measured as the sum of the compensation of employees plus payroll tax minus employment subsidies) on the one hand and growth in labour productivity on the other. So, for example, if labour costs were growing at around 3.5 per cent and productivity at around one per cent, then ULCs will be growing at around 2.5 per cent. Which would look broadly consistent with the centre of the RBA’s inflation target band.

Until earlier this year, the RBA had assumed a (non-farm) labour productivity growth rate of one per cent. But in the August 2025 SMP, the central bank downgraded this productivity forecast to 0.7 per cent. In that context, the RBA thinks that in the long run the rate of wage growth consistent with inflation at target and the labour market at full employment will be equal to the midpoint of the inflation target (2.5 per cent) plus productivity growth (0.7 per cent). That gives an estimate of ‘sustainable’ long-run wage growth of about 3.2 per cent, a bit higher than the headline WPI rate in the September quarter and in line with the growth in the private sector WPI.

Complicating things just that little bit more is that this 3.2 per cent figure for wage growth applies to a national accounts-based measure of wage growth, known as Average Earnings in the National Accounts (AENA), and not the WPI. The last estimate we have for AENA is for the June quarter of this year, when on a non-farm basis it was running at 4.9 per cent. With non-farm labour productivity falling 0.1 per cent over the year, annual growth in ULCs was around five per cent. In the case of the WPI, the RBA thinks the sustainable rate of annual wage growth is a bit lower than the AENA-based estimate, at around 2.9 per cent. *

Importantly, these are long-run concepts and as such do not tell us too much about any immediate implications for inflation. But they do serve to caution that eventually, in the RBA’s worldview either productivity growth will have to accelerate and/or wage growth will have to slow from their current rates.

* The reason for the gap is because AENA and the WPI measure different things. The WPI measure is designed to exclude the impact of changes in the industry composition of the labour force, changes in hours worked, and changes in the characteristics of employees. The idea is that by removing compositional factors it captures a pure price change for labour, in a way that is analogous to the CPI. But some productivity growth in the economy is likely to reflect compositional changes, such as a shift in employment between industries with different levels of wages and productivity. In contrast, AENA includes changes in bonuses, overtime payments, and the impact of workers changing to jobs with different pay levels.

Real wages rose again but remain below pre-pandemic levels

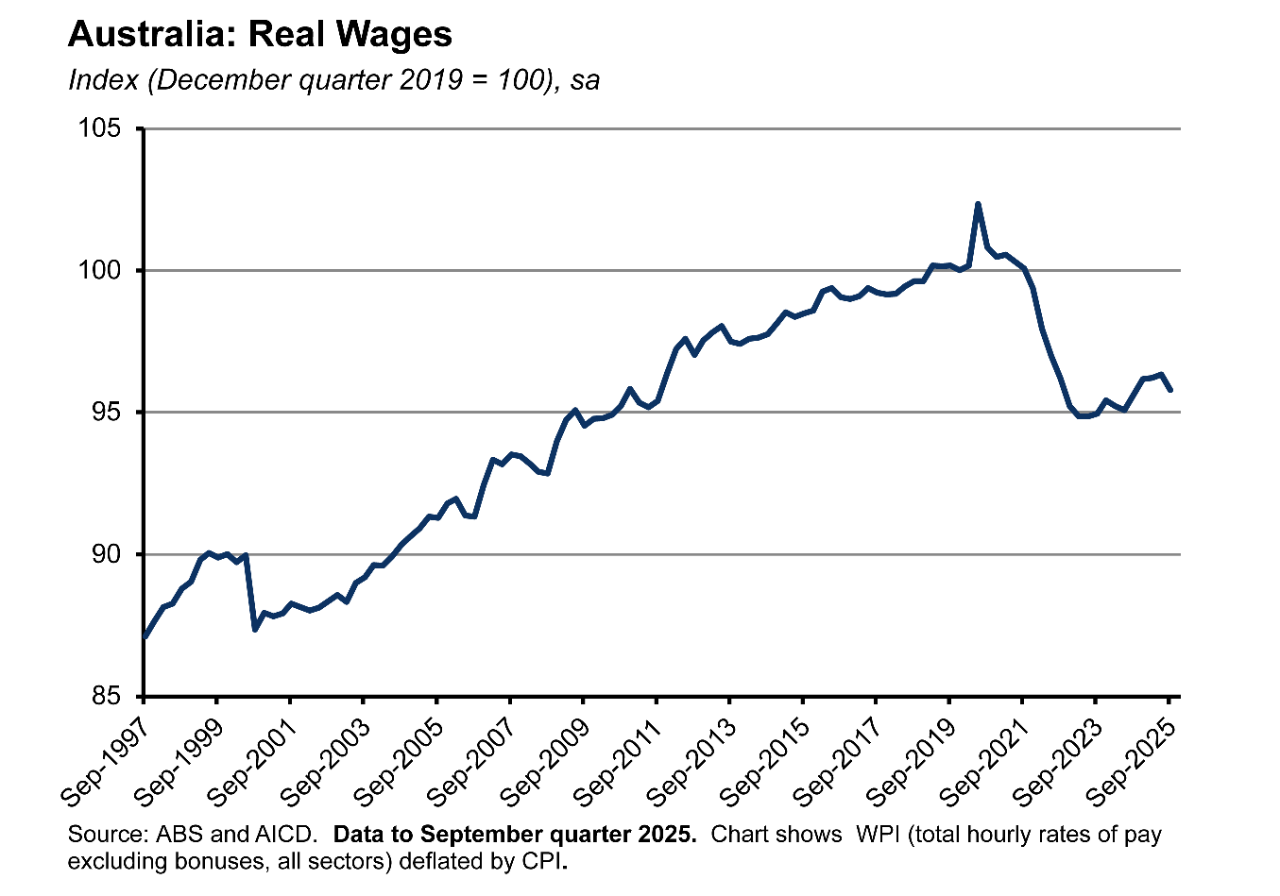

Last quarter’s headline annual growth of 3.4 per cent in the WPI was just enough to outpace the 3.2 per cent annual growth in the Consumer Price Index also recorded in that quarter. That left real wage growth in positive territory for an eighth consecutive time, following a sequence of ten straight quarters of decline.

That result still leaves real wages below their pre-pandemic levels on a WPI basis, although note that this does not consider the impact of income increases due to bonuses, promotions, or changes in employment role.

The RBA Minutes recap the case for leaving monetary policy on hold

The RBA has published the Minutes of the 3-4 November 2025 MPB meeting, at which the MPB members voted unanimously to leave the cash rate target unchanged at 3.6 per cent. Unsurprisingly, the details align with the discussion in the November Statement on Monetary Policy and in the governor’s press conference following the meeting:

- The September quarter 2025 inflation reading had been ‘materially larger’ than the projections in the August 2025 SMP and ‘a little larger’ than the RBA had anticipated at the time of the September MPB meeting. The MPB judged that some of the increase in underlying inflation was likely to reflect volatile or temporary factors (fuel and travel, council rates), but some could also prove persistent (new dwelling costs, market services), implying less capacity in the economy than previously assumed.

- Members ‘noted’ the weakening of the labour market that appeared in the September 2025 monthly release, but the MPB also reckoned that a ‘wide range of indicators suggested the labour market was still a little tight.’ As discussed last week, the October 2025 labour market results will have since served to reinforce that judgement.

- The MPB sounded cautious about the extent to which the current setting of policy remained restrictive, with the Minutes reporting that ‘members judged that financial conditions were still slightly restrictive but that it was also possible this was no longer the case.’

- On balance, the MPB thought that the information flow since its previous meeting had been consistent with one or more of: Demand proving a little stronger than forecast; supply capacity a little weaker; and/or the restrictiveness of current policy settings a little lower than assumed.

As a result of these considerations:

‘…members agreed there was no need to adjust the cash rate target at this meeting…members determined that they could afford to be patient while assessing what the incoming data reveal about their judgements on the extent of spare capacity, the outlook for the labour market and the degree of restrictiveness of monetary policy.’

As noted earlier, some RBA watchers have highlighted the discussion in the Minutes around the RBA’s latest projections, which see underlying inflation remaining above the 2.5 per cent midpoint of the inflation target band through 2027. Here, the Minutes commented that ‘this forecast was also predicated on 30 basis points of reduction in the cash rate and…an alternative staff projection based on the assumption of no further change in interest rates had inflation settling closer to the midpoint.’

At its meeting, the MPB also considered scenarios under which the ‘incoming data’ could lead to the cash rate target remaining unchanged along with scenarios which would warrant further policy easing.

For example, the case for staying on hold would be reinforced by: A stronger recovery in demand and the consequences for employment growth – perhaps due to continued resilience in global growth or a more robust recovery in household spending; the MPB recognising that the supply capacity of the economy was weaker than it had estimated – manifesting in persistently higher inflation or weaker productivity growth (recall that the RBA has already downgraded its estimates for productivity growth once this year); or the MPB revisiting its view that monetary policy was still slightly restrictive.

In contrast, the case for further policy easing could be made by: Any further material weakness in the labour market, for example if uncertainty reduced hiring demand or cost-cutting triggered rising job layoffs; or households remaining cautious and therefore keeping spending weaker than the RBA currently expects.

Still in data-dependent mode, the MPB ‘agreed that it was not yet possible to be confident about which of these scenarios was more likely.’

Finally, note that the Minutes did not report any scenarios involving a rate increase.

Other Australian data points to note

Providing more data on wage developments this week, the ABS Monthly Earning Indicator said that total wages and salaries paid by employers reached $108.8 billion in September this year, up 5.3 per cent from the same month last year. The Bureau also reminded readers that seasonal bonuses drive wage growth in September, with five industries (Mining, Utilities, Retail trade, Information media and telecommunications, and Financial and insurance services) paying periodic bonuses.

The State Accounts for 2024-25 are now available from the ABS. Gross State Product (GSP) rose in all states and territories in 2024-25, with growth ranging from 3.5 per cent in the ACT to 0.9 per cent in New South Wales.

The ABS has published the 2023-24 Energy Account which reports declines in energy use by households (down 0.7 per cent) and industry (down 0.1 per cent) over the year. Energy exports, on the other hand, were up 3.1 per cent driven by exports of black coal.

Further reading and listening

- The Concluding Statement of the IMF’s 2025 Article IV Mission to Australia. According to the Fund, we are ‘managing a soft landing amid global uncertainty’ while lifting our growth prospects ‘requires continued efforts to tackle fiscal and structural challenges.’ Included in the latter are recommendations to consider ‘an increase in indirect taxation, the reintroduction of a resource revenue tax, and removing income tax exemptions [which] could offset lower corporate and labour taxes, thereby lowering the cost of capital and increasing incentives for investment and work.’ It also says the ‘focus should be on easing the overarching binding constraints including significant regulatory compliance costs, skills mismatch, and falling R&D expenditure.’

- The ABS introduces the Consumer Price Index’s new monthly time series.

- A new position paper – on Portfolio Resilience – from Australia’s Future Fund. Core to the approach is the Fund’s view ‘that the world going forward will be characterised by deep structural change across geopolitics, economies, policy and markets’ and that this will create more conflict (international and domestic), more intervention (fiscal policy and re-industrialisation), more inflation, greater regional and sectoral divergence, more volatility and fragility leading to greater systemic risk, and more uncertainty. Key drivers will include climate change, demography, and technology. The paper also summarises the Fund’s four secular scenarios that emerge from these forces.

- John Edwards reviews Andrew Ross Sorkin’s book about the great Wall Street crash, 1929, and ponders the lessons for today.

- According to the ACCC, Australians reported nearly $260 million in losses to scams in the first nine months of this year.

- Setting a higher standard for standards. Flavio Menezes reckons Australia has more than 9,000 voluntary standards ‘shaping almost every part of daily life’ of which roughly one-third are mandatory due to direct government reference in regulation. Unfortunately, he writes, our current approach to adopting and maintaining them ‘often adds cost, delay and uncertainty.’

- Two pieces from the e61 Institute: one asking whether GST exemptions are fair, and one on the economics of the government’s Solar Sharer Offer.

- More on the cautious rate of Australian business adoption of AI (refers to one of last week’s RBA links).

- The IEA’s World Energy Outlook 2025 highlights some of the mounting contradictions in the drivers of the energy outlook, noting that even as climate risks are rising, the momentum behind national and international efforts to reduce emissions is waning. Likewise, while renewables set new deployment records last year, consumption of oil, natural gas, and coal also all set their own record highs. Reflecting this new reality, the IEA’s Current Policies Scenario (CPS) - which are based only on actually enacted laws and measures - has demand for oil and natural gas continuing to grow through to 2050 (although it projects demand for coal falling into decline before 2030).* Under the CPS, annual CO2 emissions in 2050 are little changed from the 38 gigatonnes recorded in last year, consistent with a projected temperature increase of almost 3C. Other points of note from the report include a revival of fortune for nuclear energy and the increasing importance of electricity. The latter story encompasses the explosive demand for data centres and AI in advanced economies and China. According to the IEA, investment in data centres in expected to reach US$580 billion this year, exceeding the US$540 billion spent on global oil supply (although even a forecast tripling of the amount of electricity consumed by data centres by 2035 still represents less than 10 per cent of projected global electricity demand growth, albeit highly geographically concentrated). *The IEA had discontinued publication of the CPS in 2020 but in a telling sign of the times has now reinstated it.

- The WSJ with a deep dive into the AI investment boom in the United States.

- The disconnect between global policy uncertainty and global sentiment.

- The Paris Agreement at Ten Years (OECD survey of expert opinion).

- Some thoughts regarding rewiring trade for a warming world.

- On the costs of euroscepticism.

- The World Ahead 2026 from The Economist magazine, including the editor’s ten trends to watch next year.

- Odd Lots talks to Paul Kedrosky on the AI bubble.

- The New Bazaar podcast considers the lessons of the Rare Earths Shutdown.

- Branko Milanovic on the Great global transformation (LSE Events podcast).

- Bloomberg’s Trumponomics podcast on the economic puzzle posed by US tariffs.

- Finally, the FT’s Martin Wolf suggests his best economics books of 2025. So far, I have only read one of these (Klein and Thompson’s Abundance), but the Dan Wang and Branko Milanovic books will be heading my way for Christmas and are slated for summer reading…

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content