As expected, the RBA’s Monetary Policy Board (MPB) decided to lower the cash rate target by 25bp to 3.85 per cent this week. Australia’s policy rate now has a ‘three’ in front of it for the first time since early June 2023.

When the RBA delivered 25bp of monetary policy easing back in February 2025, we characterised that decision as a ‘cautious rate cut.’ That description captured the way in which Martin Place sought to balance progress on disinflation with its ongoing concerns regarding a tight labour market. It also reflected a clear message from Governor Bullock that the central bank was in no hurry to deliver additional rate relief. The same caution then continued into the April 2025 meeting which saw the board leave the cash rate unchanged. In contrast, when asked in this week’s press conference about how she would describe the outcome of the latest MPB meeting, the governor described it as a ‘confident’ cut. She also confirmed that the board had considered the case for a larger 50bp reduction and indicated that the central bank stood ready to deliver more cuts if needed. The shift in tone was stark and markets have responded by pricing in another rate cut as early as the next MPB meeting in July.

That tone shift from hawkish to dovish reflects the deterioration in the international economic environment since the April MPB meeting, plus the ongoing progress with disinflation. The move to ease monetary policy this week is likewise consistent with new forecasts presented in the RBA’s May 2025 Statement on Monetary Policy (SMP). The revised baseline projections see growth and inflation slightly lower and unemployment slightly higher than was the case in February. The central bank is also emphasising the dramatically elevated level of uncertainty it currently faces in assessing the economic environment: according to one count, the May SMP deploys the words ‘uncertain’ and ‘uncertainty’ more than 130 times.

So, confident and uncertain? Yes: the confidence refers to this week’s decision, while the uncertainty refers to the outlook. Overall, the key judgement in all this is that Martin Place judges that the trade conflict plus the accompanying uncertainty shock will be disinflationary for the Australian economy. As a result, the RBA looks set to accelerate the journey it began in February this year to take the cash rate back to a neutral setting.

More on the MPB meeting and the updated SMP forecasts below. We also review last week’s downgrade of US sovereign risk and cast an eye over the Productivity Commission’s current work on the ‘Five Pillars’ of Australian productivity.

Finally, a reminder that this year’s National Economic Update 2025 is coming up next month. I hope some readers can join us for what should be an interesting discussion: there will be plenty to talk about.

The RBA has delivered a second rate cut

In a decision that had been widely anticipated by markets and by RBA-watchers, the RBA’s Monetary Policy Board (MPB) announced a 25bp reduction in the cash rate target this week, taking the policy rate down to 3.85 per cent. The move is the second of the current easing cycle, following on from a 25bp cut in February this year. According to the accompanying policy statement:

‘The Board judged that the risks to inflation have become more balanced. Inflation is in the target band and upside risks appear to have diminished as international developments are expected to weigh on the economy. With inflation expected to remain around target, the Board therefore judged that an easing in monetary policy at this meeting was appropriate.’

The MPB’s decision to cut this week largely reflects the combined impact of two factors.

First, on the international front, the RBA is focused on the deterioration in the international economic outlook and the accompanying elevated levels of uncertainty as to the final scope of the Trump 2.0 tariffs; the policy response of other countries; the consequences for expenditure decisions by households and firms; and with respect to geopolitical developments. Not only is all this uncertainty expected to drag down the level of global economic activity, but it has also ‘contributed to a weaker outlook for growth, employment and inflation in Australia.’ Critically, the RBA’s base case is that the Trump 2.0 trade and uncertainty shock and its associated fallout will prove disinflationary for the Australian economy.

Second, on the domestic front, the central bank is feeling increasingly comfortable about the inflation picture. The March quarter CPI numbers showed underlying inflation dropping below three per cent for the first time in more than three years while headline inflation remained within the two-to-three per cent target band for a third successive quarter. Updated RBA forecasts (of which more below) now show underlying inflation remaining around the mid-point of the target range for much of the forecast period and moreover doing so conditioned on a lower trajectory for the cash rate. The MPB does remain concerned about the ongoing tightness of the Australian labour market. But even then, the risk of a softer-than-projected recovery in domestic consumer spending is an important offsetting factor.

Should downside risks around the global economy materialise, then the central bank also stands ready to do more:

‘The Board considered a severe downside scenario and noted that monetary policy is well placed to respond decisively to international developments if they were to have material implications for activity and inflation in Australia.’

New RBA forecasts anticipate slower growth and lower inflation

This week also brought the publication of the May 2025 Statement on Monetary Policy (SMP) which included updated forecasts from the central bank. The new baseline projections rest on four key judgements or assumptions:

- In the global economy, average bilateral US-China tariffs remain around current levels, while US tariffs on other trading partners remain at ten per cent; Beijing eases fiscal and monetary policy to offset the hit to Chinese growth; and global uncertainty gradually declines.

- As a result, China sees only a modest slowdown in economic growth with policy stimulus offsetting most of the drag from tariffs and uncertainty.

- Elevated global and domestic uncertainty together have only a limited adverse impact on business and household activity in Australia.

- And in net terms, global trade developments prove to be disinflationary for Australia as lower domestic economic activity leads to an easing in labour market conditions and lower domestic inflationary pressures.

On that basis, and relative to its February 2025 forecasts, the RBA has revised down its expectations for activity in Australia’s major trading partners, pared back its projections for Australian economic growth, nudged up its predictions for the unemployment rate, and trimmed its forecasts for underlying

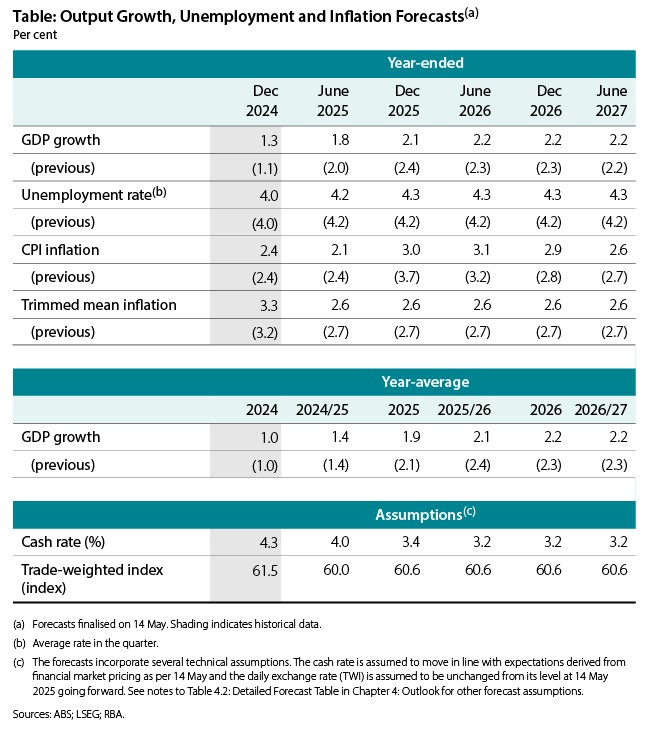

Source: RBA Statement on Monetary Policy May 2025

The RBA now thinks that trimmed mean inflation will run at around 2.6 per cent through until mid-2027 (although do note that headline inflation is still expected to move – temporarily – through the top of the target band if by less than before), that growth will pick up to 2.2 per cent by next year, and that the unemployment rate will peak at 4.2 per cent. These projections include the technical assumption – not forecast – of a cash rate that moves in line with market pricing at the time the forecasts were constructed, falling to 3.4 per cent by the end of this year and then easing further to 3.2 per cent by mid-2026.

In recognition of the prevailing level of global economic uncertainty, the SMP also canvasses two alternative scenarios: (1) a ‘trade war’ scenario under which ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs are reimposed, tariffs on all Chinese imports are returned to the very high levels of early April 2025, global uncertainty is higher and more persistent, and there is a significant negative shock to confidence; and (2) a ‘trade peace’ scenario under which there is a sharp de-escalation in trade tensions that returns US tariffs and global uncertainty levels back to 2024 levels. Under the first of these scenarios, the unemployment rate rises to nearly six per cent, inflation falls to around two per cent by end 2026, and growth slows sharply. Under the second, the unemployment rate remains around its current level, inflation remains stuck above the midpoint of the target range, and the recovery in Australian growth is more pronounced. (The cash rate is assumed to follow the same trajectory in line with market pricing in all three scenarios.)

The RBA judges that both the baseline scenario and the ‘trade war’ scenario are likely to be disinflationary for the Australian economy. In a caveat to the ‘trade war’ scenario, however, the SMP does concede that a protracted dispute could instead lead to greater global inflationary pressures on net. Disrupted supply chains could generate higher costs for businesses and hence higher prices; damage to the supply side of the economy via lower investment, less innovation, and greater resource misallocation could lower productivity growth and worsen demand-supply imbalances; and higher prices could push up inflationary expectations. Under those conditions, the RBA would have to balance weaker growth and higher unemployment on the one hand with higher inflation on the other: that is, Martin Place would face the unpleasant policy choices raised by a stagflationary shock.

Further rate cuts look to be on their way

In response to this week’s move and the accompanying messaging from the RBA, financial markets are now pricing in a more aggressive policy easing profile from the central bank. At the time of writing, that included predictions for a July rate cut.

Readers might recall that, as discussed in our analysis of February’s rate cut, a decent estimate for a neutral setting for the case rate target is around 3.5 per cent. It follows that, at a cash rate target of 3.85 per cent, current policy settings remain somewhat contractionary – a factor that the RBA acknowledged in this week’s policy statement:

‘The Board assesses that this move [to cut by 25bp] will make monetary policy somewhat less restrictive.’

That leaves scope for further easing to return policy to neutral, let alone to deliver any stimulus in the event of a significant adverse shock. After the RBA’s February 2025 cut, we had suggested that this meant there was scope for two or three more rate cuts in the current cycle, but then cautioned that the RBA was likely to move slowly. Since then, the transformation in the international environment, the central bank’s subsequent assessment that on balance this shift is set to be disinflationary for the Australian economy, and Martin Place’s concerns about the economic impact of the prevailing elevated levels of uncertainty all argue that the next rate cut will now more arrive sooner rather than later – potentially at either the next (7-8 July) or the following (11-12 August) MPB meeting. And if the international situation deteriorates, the cycle could be deeper too, requiring more rate cuts to support activity.

Farewell to AAA status for US sovereign risk

Last Friday, Moody’s Ratings downgraded the Government of United States of America’s long-term issues and senior unsecured ratings by one notch, from AAA to Aa1. It also revised the outlook on those ratings to stable from negative. (Moody’s and S&P now only award their top AAA rating to 11 economies, while Fitch does so for just ten. Note that all three agencies still rate Australia at AAA.)

Last week’s downgrade means that none of the three big rating agencies now rate the United States at AAA. S&P decided that US risk no longer merited AAA status back in 2011 while Fitch delivered its downgrade more recently, in 2023. Moody’s cited the decline in US fiscal metrics as a key factor driving last week’s downgrade, noting that the country’s government debt and interest payment ratios were already at levels significantly higher than similarly rated sovereigns. And at heart, all three sovereign downgrades reflect the judgement that the US political system is now incapable of delivering a credible debt and deficit reduction plan. In the case of the latest downgrade, recent developments have convinced Moody’s that the fiscal position will likely get worse from here, with the agency expecting the US federal budget deficit to widen from 6.4 per cent of GDP in 2024 to almost nine per cent of GDP by 2035.

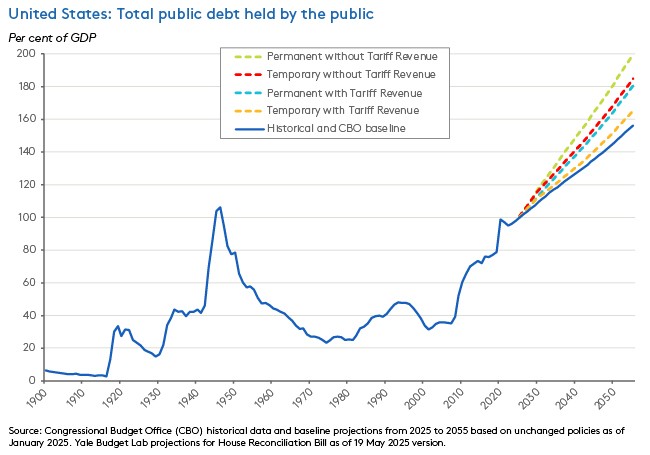

That fiscal judgement looks consistent with the consensus. Back in March this year, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) presented estimates of what the US federal debt and deficit situation would look like on unchanged policy settings (as of January 2025). According to the CBO, under that scenario a projected sequence of large deficits (of five per cent of GDP and above) would see debt held by the public climb to a record 107 per cent of GDP in 2029 and then continue to rise to 156 per cent of GDP in 2055. And those CBO projections could well underestimate the likely trajectory for debt and deficits, assuming Congress pushes ahead with the ‘one big, beautiful bill’ that the Trump administration is currently advocating. For example, the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CFRB) reckons that the budget reconciliation bill currently under consideration by the House of Representatives would increase US federal debt by US$3.3 trillion between 2025 and 20234, including interest costs. Moreover, that number relies on a series of what the CFRB calls ‘timing gimmicks’ – that is, the bill front-loads tax cuts and new spending measures and schedules them to end in 2028 while back-loading savings measures to begin after 2028. That temporal sleight of hand implies a looming 2028 fiscal cliff of up to US$4.8 trillion.

Calculations by the Yale Budget Lab yield similar numbers. They suggest that, as currently written, the bill under consideration by the House would add US$3.4 trillion to US government debt over the period 2025-34 or US$15.3 trillion between 2025 and 2055. If the bill’s temporary provisions were instead made permanent – a likely outcome given experience – then the cost over the 2025-34 period would rise to US$5 trillion, and over the 2025-2055 period to US$23.7 trillion, which the Budget Lab says could see the debt-to-GDP ratio hit 200 per cent by 2055.

Importantly, the inclusion of potential revenue from tariff rates as of 12 May would reduce those numbers, although it would still see a rising debt burden. For example, the Yale Budget Lab estimates that including potential tariffs revenues would see the cost of the bill under the second scenario discussed above fall from US$5 trillion over the 2025-34 period to US$2.5 trillion and decline from US$23.7 trillion to US$13.5 trillion over the 2025-2055 period. Even so, that would still imply a debt to GDP ratio of 180 per cent by 2055 (see chart).

How does all this fit into the bigger international economic narrative about Trump 2.0, tariffs, and the global uncertainty shock? There are several points of intersection. One of these is the role of tariffs as an additional source of budget revenue to close at least some of the fiscal gap. This presumably is the calculation that sits behind the new near-universal tariff of ten per cent introduced on Liberation Day and may also influence other tariff negotiations. Another point of intersection is the interaction with interest rates and the US dollar, with the initial market response to the downgrade to sell down US government bonds and the greenback. Closely related are the implications for the relative attractiveness of US assets, as although a one-notch downgrade alone is unlikely to be a major factor in driving asset demand, the downgrade fits neatly into ongoing market narratives around the end of US exceptionalism.

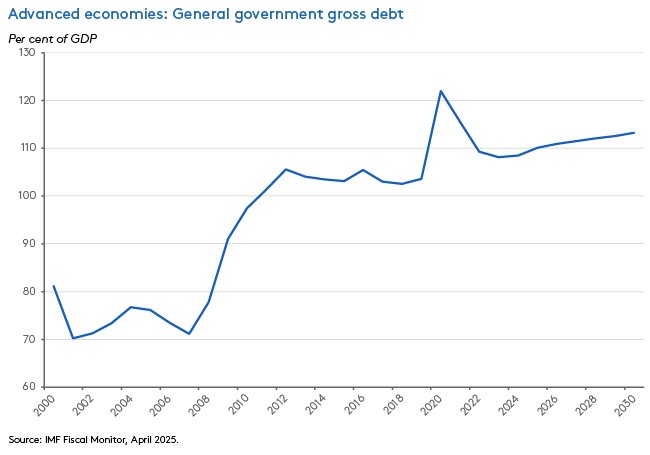

It is also part of a broader global narrative specific to debt and deficits that is set out in the latest (April 2025) IMF Fiscal Monitor. Then, the Fund warned that the global fiscal outlook has also deteriorated, with global public debt now projected to reach nearly 100 per cent of world GDP by the end of this decade, while average advanced economy debt is forecast to climb to more than 113 per cent of GDP over the same period. Debt has already been driven up by the fiscal policy responses to the global financial crisis and later to the COVID-19 pandemic and the IMF is now citing the Trump administration’s tariff announcements and the consequent increases in policy uncertainty and financial market volatility as important new contributors to fiscal risk, along with higher bond yields and rising defence spending in some key economies.

Australia’s familiar Five Pillars of Productivity

Late last year, the Australian government tasked the Productivity Commission (PC) with undertaking five inquiries to identify priority reforms under each of the five pillars of the government’s own productivity growth agenda. For each of these five pillars, the PC has now identified a concise list of two-to-four policy reform areas:

Pillar One. Creating a more dynamic and resilient economy:

- Support business investment through corporate tax reform

- Reduce the impact of regulation on business dynamism

Pillar Two. Building a skilled and adaptable workforce:

- Improve school student outcomes with the best available tools and resources

- Support the workforce through a flexible post-secondary education and training sector

- Balance service availability and quality through fit-for-purpose occupational entry regulations

Pillar Three. Harnessing data and digital technology:

- Support safe data access and handling through an outcomes-based approach to privacy

- Unlock the benefits of consumer data through effective access rights and controls

- Enhance reporting efficiency, transparency and accuracy, through digital financial reporting

- Enable AI’s productivity potential

Pillar Four. Delivering quality care more efficiently:

- Reform of quality and safety regulation to support a more cohesive care economy

- Embed collaborative commissioning to increase the integration of care services

- A national framework to support government investment in prevention

Pillar Five. Investing in cheaper, cleaner energy and the net zero transformation:

- Reduce the cost of meeting carbon targets

- Speed up approvals for new energy infrastructure

- Encourage adaptation by addressing barriers to private investment

The Treasurer has declared that the government’s economic agenda for its second term will be heavily influenced by the need to deliver a recovery in Australia’s productivity performance. In that context, the five pillars provide some guidance as to where Canberra will be looking for productivity gains. The PC is also seeking further feedback on its approach from stakeholders, which offers the opportunity to influence its advice government.

The PC delivered its last five-year Productivity Inquiry report to government on 7 February 2023. The Advancing Prosperity report - the sequel to 2017’s Shifting the Dial report - also focused on five key themes: creating a more dynamic and competitive economy; building an adaptable workforce; harnessing data, digital technology and diffusion; efficiently delivering government services; and securing net zero emissions at least cost. Sharp-eyed readers will have noticed the significant degree of overlap here. And this should not be surprising: there is a broad degree of consensus around the nature of the productivity challenges facing the Australian economy. What continues to prove more troublesome is the politics of delivering economic reform in response.

What else happened on the Australian data front this week?

The ABS said that employee earnings (total wages and salaries paid by employers) in March 2025 were up 0.9 per cent over the month (original basis with calendar adjustment) to stand 5.8 per cent higher over the year.

The S&P Global Flash Australia PMI Composite Output Index slipped to 50.6 in May 2025 from 51 in April, a three-month low. The Flash Australia Services PMI Business Activity Index fell to a six-month low of 50.5 while the Flash Australian Manufacturing Output Index dropped to a three-month low of 50.6. Even so, all three indices remained in positive territory, consistent with an ongoing expansion in activity, albeit at a weakening rate. Business confidence fell for a fourth consecutive month to its lowest level since October 2024. There were also signs of softening inflationary pressures in the latest survey results, as the rate of growth in both input costs and output prices slowed relative to April, with input cost inflation falling to a three-month low. Firms meanwhile continued to report sustained growth in employment.

The ANZ-Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence Index edged up by 0.5 points to 88.8 points in the week ending 18 May. Weekly inflation expectations were unchanged at 4.5 per cent.

Other things to note . . .

- In the AFR, Productivity Commission (PC) chair Danielle Wood welcomes the Treasurer’s focus on productivity.

- Also from the PC, Dr Jenny Gordon delivered the 2025 Richard Snape lecture on Economic policymaking in a more uncertain world.

- A new e-book from Richard Baldwin on Trump’s great trade hack. Full contents here.

- Paul Krugman on a Liz Truss moment for America?

- An updated look at the rise and retreat of US inflation.

- A deep dive into what’s gone wrong with UK productivity growth.

- Understanding the decline in US labour mobility.

- The Economist magazine examines economists’ confusion over the top rate of tax.

- Can we trust social science?

- Nowcasting global trade from space.

- Visualising the oceans’ circulatory system.

- Alexander goes West (a silly counterfactual).

- The FT’s economics show asks, how should central banks respond to tariffs?

- The Past, Present, Future podcast has been running a series on Ideas of Globalisation, including (but not limited to) episodes on Hoover and Smoot-Hawley, Central banks vs the people, the crisis of the 1970s, and a culminating discussion with economist Dani Rodrik on what’s gone wrong.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content