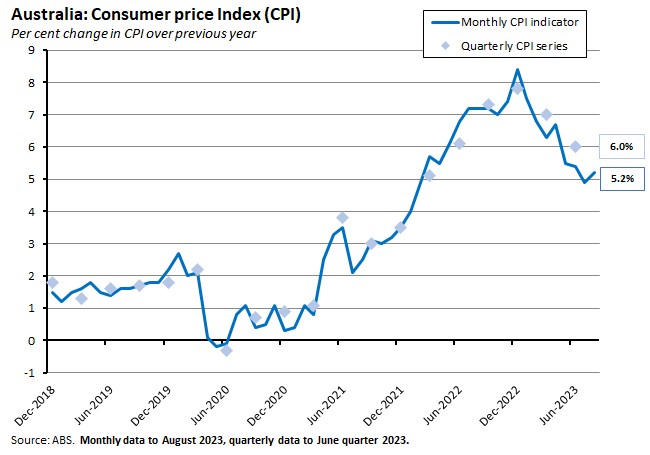

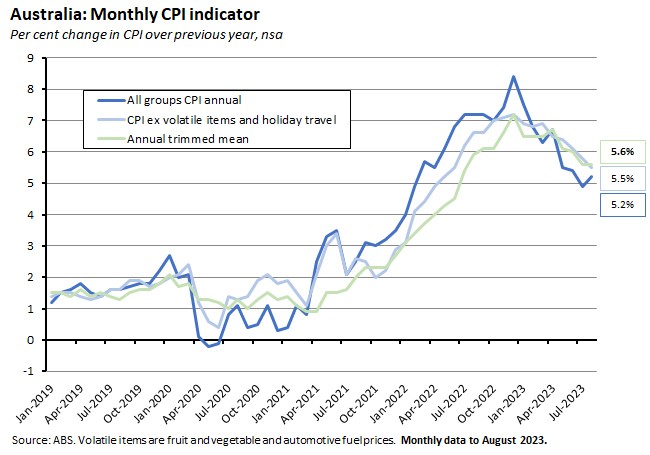

The most important data point this week was the release of the August 2023 monthly CPI indicator. This showed the annual rate of inflation increasing to 5.2 per cent from 4.9 per cent in August, propelled upwards by a sharp rise in automotive fuel prices. The fuel price effect was widely expected – we flagged it last week – while the 5.2 per cent print was exactly in line with the median market forecast. Underlying measures of inflation were either flat (the trimmed mean, unchanged from its July result of 5.6 per cent) or down (the CPI excluding volatiles and inflation fell from 5.8 per cent in July to 5.5 per cent in August). Alongside a soft reading for August retail sales this week, as well as a sharp quarterly drop in the ABS vacancies series, albeit to still remarkably elevated levels, the CPI numbers do not look sufficient to shift the RBA away from its extended pause at next week’s meeting. They are, however, a reminder that higher global oil prices could yet complicate the RBA’s battle to return inflation to target, meaning that the possibility of a future ‘insurance policy’ rate hike cannot be completely ruled out.

I’m on the road over the coming week, so the next Weekly Note might have to be a shorter than usual edition. Meanwhile, there’s more detail below on this week’s data releases, plus the usual round-up of links.

Monthly CPI Indicator shows headline inflation rose in August 2023

The ABS said the Monthly Consumer Price Index (CPI) Indicator rose 5.2 per cent over the year to August 2023. That was higher than the 4.9 per cent rate reported in July, but was exactly in line with the market’s consensus forecast. It also ended a run of three months of falling inflation rates.

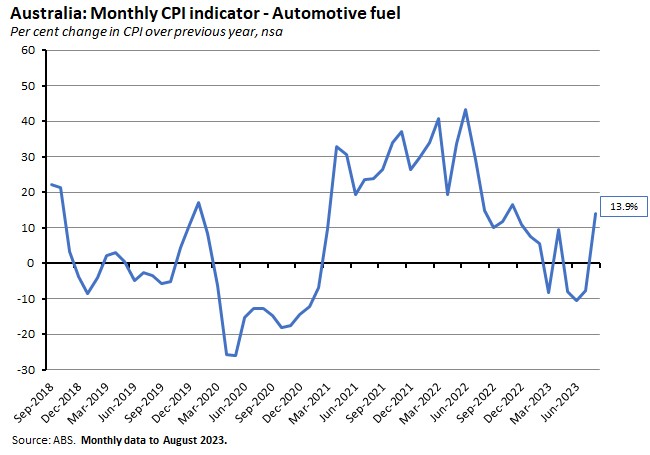

A key driver of the August result was an increase in the price of automotive fuel, which rose 9.1 per cent over the month to be 13.9 per cent higher over the year. The monthly increase reflected recent rises in petrol prices, while the annual result was also a product of base effects – automotive fuel prices fell 11.5 per cent in August 2022.

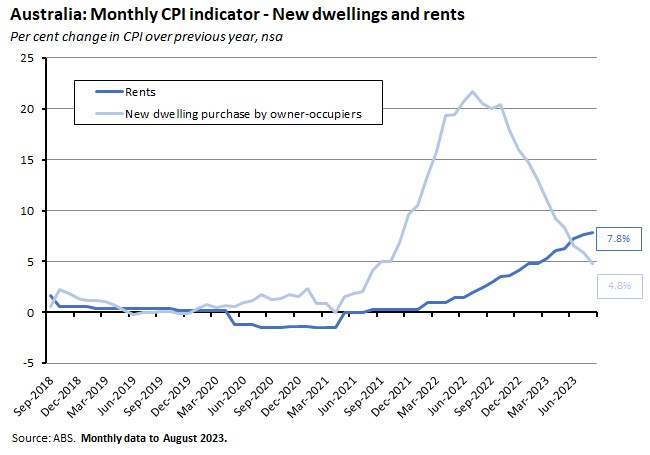

The housing sector was another important contributor to price rises last month. While the annual rate of increase in new dwelling prices slowed to 4.8 per cent (its lowest rate since August 2021), rent prices rose by a strong 7.8 per cent.

Other noteworthy price developments last month included:

- Increases in electricity prices (up 12.7 per cent) and gas prices (up 12.9 per cent), due to higher wholesale prices. But the ABS noted that rebates from the Energy Bill Relief Fund reduced the impact of electricity price hikes on the CPI - prices fell 1.3 per cent over August, but in the absence of the rebates, they would have risen by 0.5 per cent.

- The annual rate of increase for food and non-alcoholic beverages slowed from 5.6 per cent in July to 4.4 per cent in August.

- Holiday travel and accommodation prices rose 6.6 per cent over the year, up from 5.3 per cent in July.

- Insurance prices rose 14.7 per cent over the year, up from 14.2 per cent in July. According to the ABS, this was the highest annual price movement since the start of the monthly CPI indicator, reflecting higher premiums driven by rises in reinsurance and natural disaster costs.

With much of the increase in the August inflation outcome reflecting the impact of (volatile) automotive fuel prices, measures of underlying inflation were either flat or down over the month. The rate of increase in the Monthly CPI, excluding volatile items and holiday travel, slowed from 5.8 per cent to 5.5 per cent, for example, while the Annual Trimmed mean measure of inflation was unchanged from July at 5.6 per cent.

We said last week that, in the context of a data-dependent RBA, the August Monthly CPI indicator would merit close attention since it would capture the impact of recent rises in fuel prices and a weaker Australian dollar, as well as provide an update on developments in services prices. The fuel price and currency effects have duly appeared in the numbers and are reflected in increases in the rate of goods inflation (up from 4.4 per cent in July to 5.1 per cent in August) and in the rate of tradables inflation (up from 1.7 per cent to 3.4 per cent over the same period). The annual rate of services inflation was unchanged at 5.6 per cent, supported by rents, holiday travel and accommodation and financial and insurance services.

So, is August’s slight increase in the annual rate to 5.2 per cent large enough to constitute the kind of ‘inflationary shock’ in the data we reckoned would be needed to make the case for a rate hike next week? On balance, it seems unlikely. The outcome was in line with market expectations and largely driven by the rise in (volatile) automotive fuel prices – something that the RBA had already flagged in last week’s minutes. Those minutes did caution that petrol prices were ‘an important input for household’s inflation expectations’ which suggests that Martin Place won’t simply dismiss the impact of higher energy prices. But with the pace of underlying inflation either unchanged (the annual trimmed mean) or down (the CPI ex volatiles and holiday travel), there wasn’t much of a ’shock’ here. Instead, the August monthly CPI result is a reminder that the disinflation process is still characterised by a degree of uncertainty and remains hostage to external shocks such as movements in the oil price – something reflected in swings in market pricing around RBA rate hikes over the period beyond next week: at the time of writing, markets were back to pricing in the possibility of one more 25bp rate hike in the current cycle.

Job vacancies fell for a fifth consecutive quarter in August, but remain high

The ABS said total job vacancies were 390,400 in August 2023, down 8.9 per cent (38,000) from the May 2023 result (seasonally adjusted) and 15.2 per cent lower than their level in August 2022. Private sector vacancies fell 9.2 per cent over the quarter and 16.5 per cent over the year to 346,600, while public sector vacancies dropped 6.3 per cent quarter-on-quarter and 3.1 per cent year-on-year to 43,800. August marked a fifth consecutive quarterly decline in the level of job vacancies, indicating that labour market conditions have continued to ease, with vacancy numbers now 18 per cent below their May 2022 peak. Likewise, the number of businesses reporting at least one vacancy also fell in August, dropping to 21.7 per cent from 24.7 per cent in May and below the 27.7 per cent peak reached in November 2022.

While the direction of change is towards easier labour market conditions, however, in absolute terms the labour market remains tight. The level of vacancies is still very high – 71.5 per cent above the pre-pandemic level in February 2020 – in what the Bureau said reflected continuing labour shortages in many industries. Likewise, the share of firms reporting vacancies is still more than double the February 2020 reading of 11 per cent.

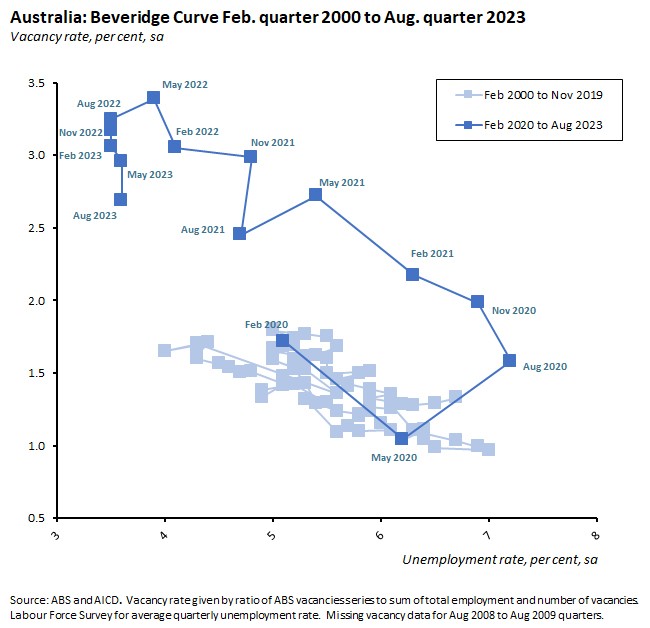

One last but important point. Plotting the vacancy rate against the unemployment rate gives us the Beveridge Curve. In theory, the Curve captures two important features of the labour market. First, changes in economic activity are associated with movements along the curve. A rise in activity leads to falling unemployment and rising vacancies, generating a move down and to the right, while a fall in activity is associating with rising unemployment and falling vacancies and a move up and to the left. Second, the distance of the curve from the origin captures the efficiency with which the labour market matches unemployed workers with vacant jobs. An inward move suggests this efficiency is improving (a given rate of vacancies is associated with a lower rate of unemployment), while an outward move suggests a decline. As we’ve discussed in previous notes one significant impact of the pandemic was a big outward shift in the Beveridge Curve:

A significant unknown was whether this outward shift represented a structural deterioration in the efficiency of the Australian labour market – perhaps due to a mismatch between workers and jobs because of the pandemic’s reallocation effect on labour demand – or was a temporary product of the highly unusual circumstances associated with COVID-19. Although we’re still in the early stages of the process, the recent run of data suggests the story may have been a temporary one, as over the past few quarters a falling vacancy rate has been associated with little change in the unemployment rate. If that pattern persists – still a big if – that would be good news for the RBA’s target of a soft landing for the Australian labour market, since it would imply that labour market tightness could continue to ease, even absent a large rise in the unemployment rate.

Retail sales growth soft in August

The ABS said retail turnover rose 0.2 per cent over the month in August 2023, (seasonally adjusted) to be up 1.5 per cent in annual terms. That outcome was a little softer than the market consensus, which had expected 0.3 per cent monthly growth. According to the ABS, given the context of high inflation and high population growth – both of which would be expected to add to nominal sales growth – this modest result reflects consumers being squeezed by cost-of-living pressures, with the Bureau highlighting that August saw the softest rate of annual trend growth at (just 1.3 per cent) in the history of the series. (See also this week’s data release on household wealth in the June quarter, covered below.)

New White Paper on employment

The Government published Working Future, its new White Paper on Jobs and Opportunities. The full document is almost 250 pages long but there is a summary factsheet here.

The White Paper echoes messages in the recent Intergenerational Report, arguing that ‘five major forces’ will shape the Australian economy in the coming decades, and that these in turn will reshape our industrial base and change how Australians live and work. The five are:

1. Ageing population.

2. Rising demand for quality care and support services.

3. Increasing use of digital and advanced technologies.

4. Transition to net zero.

5. Rising geopolitical risk and fragmentation.

In response, the White Paper sets our ‘five ambitious labour market objectives’ that the Government says will position the Australian labour market for the future:

1. A ‘new and broader objective of sustained and inclusive full employment’ such that ‘everyone who wants a job [will] be able to find one without searching for too long.’

2. Promoting job security and strong, sustainable wage growth,

3. Reigniting productivity growth by promoting investments in human capital, infrastructure, competition, and dynamism.

4. Meeting skills needs and growing Australia’s high-skilled workforce.

5. Broadening employment opportunities, including through ‘targeted, place-based approaches’.

To meet these objectives, the Paper sets out a ‘Roadmap’ with a focus on 10 areas:

1. Strengthening economic foundations, including by focusing on attaining full employment and lifting productivity growth.

2. Modernising industry and regional policies.

3. Planning for the future workforce.

4. Increasing access to ‘foundation skills’.

5. Investing in skills, tertiary education and ‘lifelong learning’.

6. Reforming the migration system, including by better targeting skilled migration and improving the employment outcomes of international students.

7. Strengthening employment services.

8. Reducing barriers to work, including by dealing with current disincentives for workplace participation.

9. Community partnerships.

10.Promoting ‘inclusive, dynamic workplaces’.

Some of the initial reaction to the White Paper has focused on the Government’s commitment to delivering full employment. The Paper notes that how ‘we define, measure and pursue full employment has significant consequences for our economy and people’ and argues it is important to distinguish between ‘statistical estimates or assumptions of cyclical full employment such as the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment, or the NAIRU…and longer-term policy objectives’ and goes on to suggest that the ‘NAIRU should not be confused with, nor constrain, longer-term policy objectives’.

It also reckons the current low unemployment rate does not provide a full picture of the extent of labour market underutilisation, which the White Paper says might be better captured by including the underemployed and the share of people outside the labour force who would like to work (‘potential workers’). On that basis, the Government reckons there are 2.8 million Australians who would like to work or work more than their current hours – equivalent to about a fifth of the present workforce.

Treasury currently estimates the NAIRU to be about 4.25 per cent while the RBA puts it at around 4.5 per cent and in that context, there was some concern that the White Paper’s ambitions would be in conflict with the RBA’s desire to return inflation to target, which in the context of the NAIRU would imply the unemployment rate would need to rise from its current level of just 3.7 per cent. But to the extent that the paper’s focus can be interpreted as aiming to lower the structural rate of unemployment over the longer term by policies such as supporting education and skills development and reducing barriers to labour market entry and also seeking to cut the frictional rate of unemployment by improving the workings of the labour market, there is no automatic conflict here, a take that the RBA has apparently confirmed.

What else happened on the Australian data front this week?

The ABS released data on Finance and Wealth for the June quarter 2023, which showed household wealth rose 2.6 per cent ($378.5 billion) over the quarter to $151.1 trillion. This was the third consecutive quarterly increase and was driven by residential land and dwellings, which contributed 2.1 percentage points to quarterly growth. Superannuation balances contributed a further 0.3 percentage points. Despite this balance sheet improvement, however, the Bureau said there were also signs of strain in household budgets, with household deposits shrinking by $6 billion in their first quarterly decline since the June quarter 2007, indicating that households were drawing on their cash reserves to meet rising cost of living pressures – something consistent with this year’s June quarter fall in the household savings ratio to its lowest level since June quarter 2008.

The ANZ-Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence Index fell 3.4 points to an index reading of 76.4 for the week ending 24 September 2023. All five subindices fell over the week, with the largest drop for future financial conditions (down 8.3 points) followed by declines in current financial conditions and future economic conditions (both down 2.8 points), current economic conditions (down two points) and time to buy a major household item (down 0.8 points). Inflation expectations rose to 5.4 per cent, which ANZ reckoned likely reflected the recent strength in petrol prices, which have averaged more than $2/litre for the past six weeks.

The ABS said the value of total engineering construction work done in the June quarter 2023 rose 2.1 per cent over the quarter (chain volume measure, seasonally adjusted) to be 17.8 per cent higher over the year. Private sector work was up 3.2 per cent quarter-on-quarter and 18.8 per cent year-on-year, while the corresponding growth rates for public sector work were 0.8 per cent and 16.5 per cent respectively.

Updated ABS numbers on causes of death in Australia in 2022. According to the Bureau, there were 190,939 deaths last year, almost 20,000 more than in 2021. Ischaemic heart disease was the leading cause of death, followed by dementia. COVID-19 was the third leading cause of death (9,859 deaths) marking the first time that Australia had an infectious disease in the top five since 1970, when deaths due to influenza and pneumonia were the fifth leading cause.

Last Friday, the government announced the Final Budget Outcome for 2022-23. The Australian general government sector recorded an underlying cash surplus of $22.1 billion or 0.9 per cent of GDP. This was Australia’s first budget surplus since 2007-08 and the highest nominal surplus on record. It was also a $17.9 billion better outcome than predicted in May’s 2023-24 Budget, which had predicted a smaller surplus of $4.2 billion (or just 0.2 per cent of GDP). That improvement relative to budget was largely driven by a $13.9 billion outperformance in terms of receipts, including $13.2 billion more in tax receipts than anticipated.

At the same time, payments were some $4 billion lower than projected. The lift in receipts was almost entirely driven by higher company tax revenues, which were $12.7 billion above budget projections, due mainly to the impact of high commodity prices on resource company revenues. Lower payments, meanwhile, reflected a combination of lower-than-expected demand for some health and aged care programs, the impact of capacity constraints and supply chain disruptions on some development and infrastructure programs, and the effect of stronger labour market outcomes.

Gross debt was $889.8 billion (35.2 per cent of GDP), while net debt was $491 billion (19.4 per cent of GDP). Gross debt was $2.8 billion higher than the estimate in Budget 2023-24 but net debt was $57.6 billion lower. The reason that gross debt was little changed despite the change in the budget bottom line was that the Australian Office of Financial Management (AOFM) decided to stick with its earlier debt issuance guidance, effective pre-funding some of the government’s financing requirements for 2023-24. The relatively larger change in net debt reflects the combined impact of a fall in the market price of bonds on issue due to rising yields, plus the accumulation of cash reserves due to stronger budgetary outcomes.

Also last Friday, the Judo Bank Flash Australia Composite PMI rose to a four-month high of 50.2 in September 2023, up from a reading of 48 in August. The return to growth in private sector activity this month reflected recovery in the services sector, with the Flash Australia Services PMI rising to to 50.5 from 47.8 (also a four-month high). But the Flash Australia Manufacturing PMI Output Index fell to 48.2 in September from 49.7 in August (a four-month low), indicating continued weakness in business conditions within the sector as the Flash Australia Manufacturing PMI fell to 48.2 from 49.6. The Composite PMI also reported that overall input cost inflation was unchanged from the August reading and above its long-term average, mainly due to services cost-inflation. In contrast, selling price inflation slipped to a five-month low as firms raised prices at a slower rate. According to Judo Bank, the survey’s inflation indicators ‘remain elevated at levels pointing to above-target CPI over the next 6-9 months…Rising oil and petrol prices may be impacting business costs and inflation expectations’.

Other things to note . . .

- John Hawkins and Selwyn Cornish assess the government’s new employment white paper. They emphasise the expansive definition of full employment highlighted above (everyone who wants a job should be able to find one without searching for too long), reckon that ‘the words, but not the numbers’ in the paper are consistent with an unemployment rate of four per cent or lower, and say that although it identifies labour productivity as crucial to increasing real wages, the white paper offers few ideas for increasing it. Peter Martin is unhappy with the absence of a stretch target for unemployment.

- Last week’s note included a link to former RBA Governor Ian Macfarlane warning that the Reserve Bank board restructure recommended by the RBA Review was a dangerous mistake. Renee McKibbin, one of the authors of the Review, disagrees, arguing that the RBA Review won’t mean handing decision-making to part-time outsiders.

- Draft papers and presentations from this year’s RBA Conference on Inflation.

- In the AFR, Chris Richardson reckons the upcoming Stage Three tax cuts will delay any RBA rate cut next year.

- The latest Quarterly Statement by the Council of Financial Regulators.

- A new working paper on housing prices and rents in Australia 1980-2023. Real median house prices across Australian cities roughly doubled between the early 1980s and 2003 and then doubled again between 2003 and 2022. Key variables driving prices are population, household disposable income, the housing stock and mortgage rates, with the last of these particularly important. Based on the 2003-2022 sub-period, the paper’s modelling suggests that in the long run, real house prices increase by around 0.5 per cent on average, following an increase of one per cent in real disposable income, while a fall of one percentage points in the real mortgage rate causes house prices to rise by 3.6 per cent. A one per cent increase in the housing stock per capita leads to an estimated long-run decrease in real house prices of 2.3 per cent on average. The results also suggest that the short-term adjustment dynamics around these long-term trends can take up to two or three years. The authors note that their findings imply that if 25 per cent more new dwellings (45,000 more or about 225,000 in total) were produced in a year – roughly in line with current government plans – then this 0.4 per cent increase in the housing stock would imply a long-term fall in real house prices of about one per cent. If this increase in construction were sustained over five years, it would reduce real house prices by about four per cent.

- The latest from the Productivity Commission on the Future Drought Fund.

- The FT says the world economy may be at a ‘milestone moment’ with the end of the global cycle of interest rate increases. AFR version. (But note that this week also saw long-term US Treasury rates hit multi-year highs as markets priced in policy rates staying higher for longer.)

- Also from the FT, a Big Read on US Treasury Bonds and market fragility. Threats to the stability of one of the world’s most important financial markets have been a recurring theme in the past couple of years.

- The IEA has updated its Net Zero Roadmap. It argues that limiting global warming to 1.5C remains possible due to the record growth of clean energy technologies including solar power and electric cars (it reckons these two combined account for one-third of emissions reductions to 2030 in its pathway) but it also estimates that annual global clean energy spending would need to rise from US$1.8 trillion this year to US$4.5 trillion by the early 2030s. That in turn would see fossil fuel demand 25 per cent lower by 2030.

- A new McKinsey Global Institute report says Asia is on the cusp of a new era.

- Related, the Economist magazine on how Asia is reinventing its economic model.

- Also related, Alfaro and Chor offer a perspective on the great reallocation of global supply chains. (Note, this is a column length version of the paper they presented earlier this year at the Fed’s Jackson Hole symposium, which I’ve linked to previously.)

- NBER Conference on the Economics of Artificial Intelligence with links to some of the papers.

- Javier Blas says Africa has suffered another Lost Decade.

- Transcript of Larry Summers speaking on what the 2023 Washington Consensus should look like.

- Mapping the migration of the world’s millionaires – Australia is back in the top spot this year.

- Institutional Investor ponders the enduring lessons of ‘Dumb Money’.

- Matt Klein and Noah Smith discuss Peak China on the China Talk podcast.

- A New Statesman audio long read on The Philosopher and the Crypto King delivers a sceptical look at Sam Bankman-Fried and the Effective Altruism movement.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content