This was another one of those quiet weeks on the Australian data front, with the only significant release being the RBA minutes. They covered familiar territory, setting out the central bank’s reasoning for leaving rates unchanged earlier this month in a way that echoed many of the arguments laid out after the August meeting. That said, they did note that Martin Place reckons that downside risks to the Chinese economy have increased.

There were some interesting parallels with the Australian monetary policy debate to be found in this week’s decision by the US Fed to leave the target range for the Fed Funds rate unchanged. Like the RBA, the Fed is currently weighing up the relative risks of delivering another ‘insurance’ policy rate hike to limit the twin threats posed by stubborn underlying inflation and higher energy prices versus the danger of over-tightening and tipping the economy into recession. One notable difference between the two central banks, however, is that the Fed has already hiked interest rates by 525bp compared to the 400bp of tightening delivered by its Australian counterpart.

In our roundup section this week, we look at recent work from the Productivity Commission on the relationships between productivity and wage growth, and between productivity and competition and dynamism. We also review the latest OECD forecasts for the world economy and consider some recent IMF research on lessons from one hundred inflation shocks that argues against any undue complacency in the current conjuncture.

RBA minutes provide familiar set of arguments

The Minutes of the 5 September Monetary Policy Meeting of the RBA Board set out the reasoning behind the central bank’s decision to leave the cash rate target unchanged for a third consecutive meeting. They reprised the same broad debate that has dominated recent meetings, weighing up the case for another 25bp increase in the cash rate target against the case for doing nothing. By now, both cases are likely to be familiar to readers.

Regarding the case for a rate increase, the Minutes cite: the RBA’s expectation that inflation will remain above the Bank’s target for an extended period (perhaps due to persistent services inflation, or to the absence of any recovery in productivity growth); the consequent risk to inflation expectations of an extended period of above-target inflation; and the likelihood that the process of returning to target will turn out to be an uneven one, with the recent rise in petrol prices the latest development set to knock prices around.

Against that, the case for no change was based on: the fact that interest rates had already been increased significantly in a short period; that the effects of all this tightening were yet to be fully felt due to lags in the monetary policy transmission process; and that the economy could slow more sharply than the RBA expects due either to weaker-than-expected consumption or to a deeper downturn in China. Overall, however, the Minutes record that:

‘On balance…members concluded that recent developments had not materially altered the outlook or their assessment that the economy still appears to be on the narrow path by which inflation comes back to target and employment continues to grow’.

The resultant decision to further extend the policy pause reflected a combination of the RBA’s confidence that inflation will return to target and the option value of waiting:

‘The recent flow of data was consistent with inflation returning to target within a reasonable timeframe while the cash rate remained at its present level. Members recognised the value of allowing more time to see the full effects of the tightening of monetary policy…given the lags in the transmission of policy through the economy.’

The RBA also continued to warn that a future rate increase is more likely than a cut – ‘members noted that some further tightening in policy may be required should inflation prove more persistent than expected’ – and that meanwhile, policy will continue to be data-dependent.

All up, there was little change here from Australia’s central bank, and as a result, our own policy outlook also remains unchanged: sans any inflationary shock in the data, there is no sign of a pressing case for additional rate hikes. In that context, the publication of the Monthly Consumer Price Index (CPI) Indicator for August 2023 – due on 27 September – will be one to watch, as it will capture the impact of recent rises in fuel prices and a weaker Australian dollar, as well as offer an update on developments in services prices.

US Fed and the RBA – Similarities and differences

This week the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) of the US Federal Reserve decided to leave the target range for the federal funds rate unchanged at 5.25 to 5.5 per cent, in a unanimous decision that was also in line with market expectations.

The Fed began tightening monetary policy in March 2022 and since then has increased the policy rate by a cumulative 525bp in an aggressive effort to return inflation to its two per cent target, driving the policy rate up to a 22-year high. This week’s pause was the second in the past three meetings (the first pause, in June 2023, followed ten consecutive rate hikes) and while financial markets correctly anticipated that the Fed would leave things unchanged, they were also looking for a potential confirmation that the phase of increasing interest rates was over.

The FOMC didn’t quite give them that, although Fed Chair Jerome Powell did use his accompanying comments (pdf) to indicate that the US central bank was now ‘in a position to proceed carefully in determining the extent of additional policy firming that may be appropriate’, that the Fed sees ‘the current stance of monetary policy as restrictive, putting downward pressure on economic activity, hiring and inflation’ and that policymakers ‘are mindful of the inherent uncertainties in precisely gauging the stance of policy’. And he flagged the impact of ‘the cumulative tightening of monetary policy’ and ‘the lags with which monetary policy affects economic activity and inflation’ as influencing future policy decisions. But he then pledged:

‘We are prepared to raise rates further if appropriate, and we intend to hold policy at a restrictive level until we are confident that inflation is moving down sustainably toward our objective.’

Powell’s messaging was supported by the presentation of the updated Summary of Economic Projections. The new ‘dot plot’ for the fed funds target rate showed 12 out of 19 participants expecting a 25bp rate increase before year-end (at either the next 31 October – 1 November meeting or the final meeting in December) versus seven seeing no change, translating into a median forecast for one more rate hike. At the same time, Fed officials also indicated that they now expect to be more cautious in unwinding rate increases next year, with the median projection putting the midpoint of the fed funds rate at end-2024 at 5.1 per cent, up from 4.6 per cent in June 2023. In part, that reflects more optimism regarding the underlying strength of the US economy, with the median forecast for Q4 GDP growth this year (2.1 per cent) and next year (1.5 per cent) now comfortably above the corresponding June projections (one per cent and 1.1 per cent, respectively) and the median forecasts for the unemployment rate (3.8 per cent for Q4:2023 and 4.1 per cent for Q4:2024) below those estimates (4.1 per cent and 4.5 per cent, respectively).

In many ways, the Fed is in a similar place to the RBA. It has delivered a large number of rate increases over a relatively short time frame and is now more inclined to ‘wait and see’ to understand what the impact of this will be on growth and inflation, particularly given the uncertainty around monetary policy lags. That means that the policy debate is moving from When will the next rate hike come? to How long will it be until the first rate cut? At the same time, the Fed, like the RBA, is also concerned about expectations management; if it signalled unambiguously that there were no more rate rises in prospect so that the next move in rates was a cut, this would risk changing market sentiment in a way unhelpful to the aim of slowing the economy to tame inflation.

So far, so familiar. But there are also interesting differences between the US and Australian experiences. Not only did the US Fed start hiking its policy rate sooner than the Reserve Bank (March 2022 vs May 2022) and deliver its first pause later (June 2023 vs April 2023) but it has also hiked rates by more (525bp vs 400bp). At the same time, US consumer price inflation is currently lower than in Australia (a headline annual rate of 3.7 per cent and a core rate of 4.3 per cent in August 2023 vs a headline rate of six per cent and an underlying [trimmed mean] rate of 5.9 per cent in the June quarter of this year, and a monthly headline rate of 4.9 per cent and an underlying rate of 5.6 per cent in July 2023).* The US unemployment rate is broadly similar to Australia’s jobless rate (3.8 per cent vs 3.7 per cent in August 2023).

So, what explains the different scale and speed of monetary policy tightening? When quizzed about this in the past (see for example this Hansard record of testimony to House Standing Committee on Economics) the previous RBA governor pointed to two main differences. First, the prevalence of flexible rate mortgages in Australia compared to the United States. As this Box in the February 2023 Statement of Monetary Policy explains, the share of outstanding mortgages with variable rates is much higher in Australia (more than 60 per cent) than in the United States (less than ten per cent) while the typical fixed rate period in Australia (around two years) is much shorter than in the United States (30 years). That has significant implications for the speed and size of pass-through from a change in the policy rate to the interest rates faced by households. Second, for much of the post-pandemic period wage growth has tended to run hotter in the United States than it has in Australia.

*The Fed’s preferred inflation gauge is not the consumer price index but rather the Core Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Price Index. The annual rate of core PCE inflation was 4.2 per cent in July this year while the headline rate was 3.3 per cent.

What else happened on the Australian data front this week?

The ANZ-Roy Morgan Australian Consumer Confidence Index rose by 2.2 points to an index reading of 79.8 in the week ending 17 September. Despite returning to its highest level since late April this year, the index remained stuck (just) below 80. That said, ANZ did note that although confidence remained ‘at very low levels’ there were also ‘some early signs of tempered optimism amongst households.’ Confidence for mortgage holders rose 4.1 points to its highest level in more than seven months and confidence for renters increased 4.7 points (although confidence among those owning their home outright fell 2.3 points).

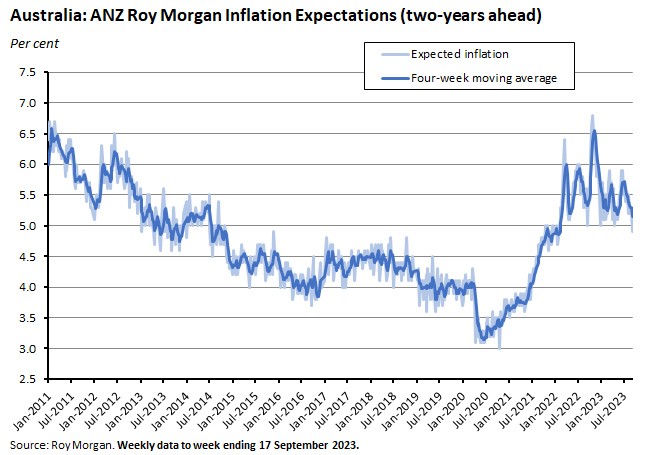

At the same time, inflation expectations fell to 4.9 per cent, recording their lowest reading since February 2022, before Russia invaded Ukraine. Last Friday, the ABS published June quarter 2023 Tourism Labour Statistics for the Tourism Satellite Accounts. According to the Bureau, there were 713,000 tourism jobs in the June quarter, down 2.7 per cent (20,100 jobs) from the March quarter of this year but up 21.3 per cent (125,300) from the same quarter last year. Relative to the pre-pandemic period as captured by the December quarter 2019, the number of tourism jobs was down 5.9 per cent (44,500). Tourism currently accounts for 4.6 per cent of filled jobs in the Australian economy. The ABS said that Labour supply services employed 327,100 people in the June quarter 2023, accounting for about 2.3 per cent of all employed people. The Bureau also reported that about 81 per cent of this group worked full time while 84 per cent did not have paid leave entitlements (August 2022 data).

Other things to note . . .

- The September quarter 2023 RBA Bulletin has been published. There are pieces on recent trends in Australian productivity, green and sustainable finance in Australia, financial stability risks from commercial real estate, the role of skills in the adoption of general-purpose technologies (GPT) in Australia, and more. The piece on GPT includes an analysis of Board skills and adoption which finds that firms with a board member with prior experience in the IT industry are significantly more likely to adopt GPT and that firms with at least one member with a relevant background saw moderate increases in profitability after adoption versus firms without any board members with a GPT background which did not see increases in profitability.

- The Productivity Commission (PC) has published a forensic look at productivity growth and wages, examining the evidence on whether wages have kept up with labour productivity over the past few decades, or whether there has been ‘wage-decoupling’ (measured here as average annual labour productivity growth less average annual producer wage growth). The PC finds the national average rate of wage decoupling between 1995 and 2022 was about 0.6 percentage points per annum. That would put Australia at the top of OECD economies in terms of the scale of wage decoupling. However, the PC argues that this aggregate result may be misleading, as it is driven by just two sectors – Mining and agriculture, which together only account for about five per cent of total employment, have seen strong wage decoupling over this period and at a combined 18 per cent of total value added, they drive most of the finding of national decoupling. In all other industries, which collectively account for the remaining 95 per cent or so of Australian employment, the PC finds that ‘the difference between productivity and wage growth has been relatively low.’ Indeed, for more than half of these industries, wage decoupling was either zero or negative. For that 95 per cent, the PC estimates that average annual real wage growth was about 1.28 per cent over the 1994-95 to 2021-22 period. That was about 0.12 percentage points lower than the 1.4 per cent growth in labour productivity, a much more modest gap than the aggregate numbers indicate.*

*Note these results are based on producer wage growth. Using consumer prices to derive consumer wages would give slightly different results: for example, over this period average annual growth in consumer wages was slower at 1.22 per cent, implying a larger gap. John Kehoe in the AFR says the PC work discussed above has ‘debunked’ claims that workers aren’t getting a fair share of productivity gains. Ross Gittins of the SMH isn’t convinced, arguing that it is the economy wide numbers that matter most in this debate.

- Also from the PC, Deputy Chair Alex Robson on Competition, dynamism and productivity - his opening statement to the House of Representatives economics committee inquiry. Robson pushes back against some of the stronger claims that Australia’s lacklustre productivity growth is a product of declining competition and business dynamism. His statement argues that (1) while lower firm entry and exit rates can be an indicator of ‘creative destruction’, they are not necessarily suggestive of broader underlying trends regarding dynamism; (2) the PC’s own analysis show that most Australian industries are not concentrated and very few became concentrated from 2006 to 2021 and therefore the claim that the Australian economy is becoming more concentrated ‘does not seem to hold up’; (3) while there is some evidence that firm markups have been increasing in Australia, ‘this evidence is plagued by measurement issues. And…interpreting evidence on markups is not straightforward; and that (4) the PC ‘does not agree’ with claims of ‘Greedflation’. (The PC’s full submission – from the first half of this year – can be found here.)

- A new working paper from the ANU’s Tax and Transfer Policy Institute considers the History of tax theory and reform concepts.

- A Grattan submission on how to tackle the rental crisis. The authors advocate boosting housing supply, reforming tax and welfare rules (reducing the capital gains tax discount and limiting negative gearing, including more of the value of the family home in the pensions asset test, getting state governments to swap stamp duty for a broad-based land tax), lifting Commonwealth Rent Assistance, working with the states to improve rental tenure security and quality, and making sure that any additional housing subsidies prioritise social over affordable housing. They also support the recent passage of the Housing Australia Future Fund (HAFF) Bill. The submission warns that strict rent caps and/or freezes would do more harm than good by increasing the scarcity of housing and leading to a large misallocation of housing across demographic groups. It also cautions that while reducing migration would improve housing affordability it would do so at the potential cost of leaving Australians overall worse off in terms of lost budget revenue (skilled migrants pay much more in taxes than they receive in benefits and public services) and lower productivity growth. (Related, the submission from the PC on the worsening rental crisis in Australia which makes some similar points.)

- In the AFR, former RBA Governor Ian Macfarlane warns that the Reserve Bank board restructure is a dangerous mistake.

- Papers from Treasury introducing OLGA (its overlapping generations model of the Australian economy) and TIM (the Treasury Industry Model).

- ABC Business summarises a recent Ross Garnaut speech on the Australian economy.

- The OECD’s September 2023 Interim Economic Outlook says that although the global economy proved to be more resilient than expected in the first half of this year, the outlook for growth remains weak due to a growing drag from tighter monetary policy and a weaker-than-expected recovery in China. World GDP growth is projected to slow from 3.3 per cent in 2022 to three per cent this year (a 0.3 percentage point upgrade from the OECD’s June 2023 forecasts) and to 2.7 per cent next year (a 0.2 percentage point downgrade). In the case of Australia, the OECD still expects economic growth to slow from 3.7 per cent last year to 1.8 per cent this year (unchanged from June) and then slow again to 1.3 per cent (a 0.1 percentage point cut). The Report includes an interesting discussion of defence spending in OECD and G20 countries

- Also from the OECD, Education at a Glance 2023. Country notes for Australia. Could The Laffer Curve make another return?

- A new IMF working paper reviews the lessons from one hundred inflation shocks in 56 countries since the 1970s. The authors find that inflation is persistent: in only 60 per cent of the episodes they consider was inflation brought back down or ‘resolved’ within five years and even in those successful cases it took an average of three years. Persistence is particularly a feature of terms of trade shocks (the 1973-79 oil shocks) where success rates were lower and resolution times longer. They also found that most unresolved inflation episodes involved ‘premature celebrations’ where inflation fell initially but then plateaued at an elevated level or even re-accelerated. Those countries that were successful in resolving inflation tended to have had tighter monetary policy, to have implemented restrictive policies more consistently over time, to have contained nominal exchange rate depreciation and had lower nominal wage growth relative to unsuccessful cases. And while these successes were associated with short-term output losses, these countries did not suffer from lower growth or real wages or higher unemployment over a five-year horizon. The authors reckon that the implications for current policy are that if history is a guide, today’s economies may face a long inflation-fighting period. They should also avoid loosening policy prematurely in response to early signs of success.

- The WSJ on the unexpected new winners in the global energy war.

- Research from Italy suggesting climate change is now shaping housing markets via impacts on search, pricing and housing demand.

- The latest BIS Quarterly Review.

- Lessons from the meltdown at Lebanon’s central bank which saw a financial engineering episode that involved transferring Lebanese banks’ foreign exchange reserves to the central bank, which used them to service government foreign debt and cover some of the country’s trade deficit. In exchange, the banks received paper assets that made them look profitable and allowed for the payment of large dividends to shareholders, but which the central bank was ultimately unable to honour.

- An FT Big Read considers the rise of surge (or dynamic) pricing and how the combination of algorithms and artificial intelligence is leading businesses to pivot away from fixed prices, as well as the potential implications for competition policy and consumer welfare.

- Also from the FT, Martin Wolf says Peak China calls are premature.

- On the rise and fall of TVs Golden Age and the ‘questionable economics’ of streaming.

- A Guardian long read on the world’s growing shadow fleet of tankers.

- Barry Eichengreen asks, Is this how globalisation ends? Eichengreen also talks about his views on globalisation in this Prospect Podcast.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content