The Victorian town of Mallacoota was ravaged by bushfires in 2019-20. Now, the community is coming together to focus on recovery and governing in a new era of regrowth.

It was one of the defining images of Australia’s 2019–20 bushfires: 4000 people huddled on the foreshore beneath an apocalyptic blood-red sky. This was Mallacoota, a tiny Victorian tourist town that, as a six-hour drive from both Melbourne and Sydney, is also one of the most isolated communities in the state.

The fire hit on the morning of New Year’s Eve and it was ferocious enough to create its own weather. “What felt like a change in wind direction was actually air being sucked into the pyrocumulus cloud formed by the blaze,” recalls Bruce Pascoe, local farmer, author of the award-winning book Dark Emu and one of the Country Fire Authority volunteers who fought the flames.

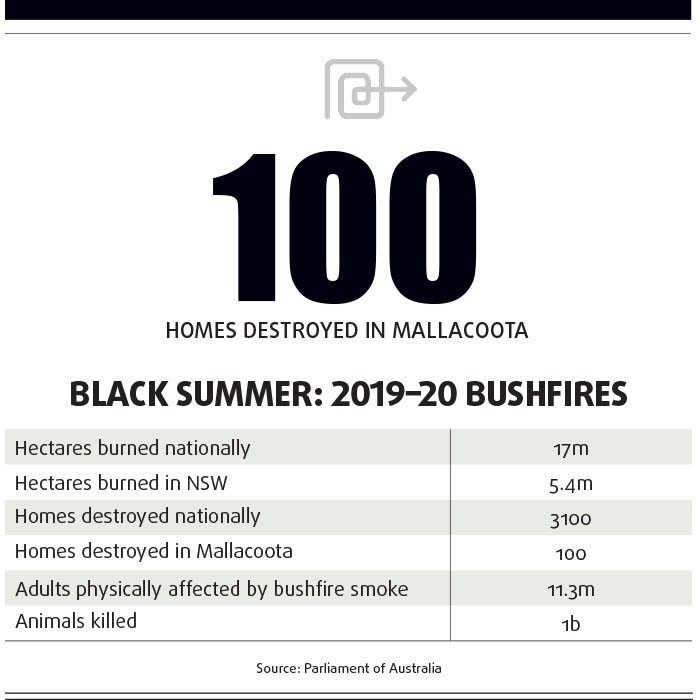

While fire crews managed to save the main street, along with its community assets and infrastructure, authorities estimate around 100 homes were destroyed. This is an unimaginable loss for a town of just over 1000 people.

“The whole community was traumatised,” says Pascoe. “My farm was impacted by fire for five weeks, but I was lucky enough not to lose my house. Psychologically, that puts me in a different category from the many people who lost much more. There is still a lot of trauma in the town.”

A plan for the future

Even as embers continued to smoulder, six residents were forming what became known as the Thinking Group, to consider the viability of a community-led recovery program. Then, in mid-January, the group met with representatives of Mallacoota’s community organisations to see if locals would support the initiative.

Encouraged by the response, the Thinking Group put together a proposed Recovery Model, which they then took to the wider community, including those who owned holiday homes in the area. When more than 500 people gave this the go-ahead, the Thinking Group arranged for the Victorian Electoral Commission to supervise an independent voting process for selecting a representative committee.

Pascoe finds it telling that no-one from the Thinking Group chose to stand for election. “I tried to encourage two or three, but they said they didn’t have the physical or mental resources — not just from the amount of work they had been doing on behalf of the community but also because they were still trying to process the trauma of fire and loss,” he says.

Finding a structure for governance

At the time of the election, the Mallacoota and District Recovery Association (MADRA) had 764 active members; 44 put their names forward and the 12 who received the most votes formed the committee. By chance this is a diverse group of six men and six women, from their twenties to their sixties, with different backgrounds and skills.

“As with any publicly elected body, especially one drawn from such a tiny community, you’re very unlikely to get expertise across all the areas you really need to tackle such an immense task,” says Mark Tregellas, Mallacoota RSL president and a member of the committee. “As a result, we’ve all been on an incredible learning curve.”

Appointing the office-bearers took barely 10 minutes, as the chair, deputy chair, treasurer and secretary were each elected unopposed. “That’s a mark of the fact we all know each other’s skills and strengths,” says deputy chair Jenny Lloyd, a former naval officer and strategic planner.

The pillars of “social, built, economic and natural environments, and Aboriginal culture and healing” provided an initial framework for forming subcommittees. However, managing so many stakeholders and sources of funding adds layers of complexity, along with a need for flexibility and collaboration.

“Our mandate is bushfire recovery, which includes economic recovery, but there is a fine line between economic recovery and economic development,” says Lloyd.

“We envisage MADRA having a three-year life span. We therefore need to partner with other local organisations, such as the Mallacoota & District Business & Tourism Association, to progress the more enduring projects that require an owner and ongoing operating costs.” Learning as you go takes time so, for the foreseeable future, the executive continues to meet every Sunday and the full committee every Tuesday. “These people are all volunteers, giving up hours of their time every day because they want MADRA to succeed,” says Tregellas.

Understanding community-led recovery

MADRA has become an incorporated body to make recommendations for the recovery of the township of Mallacoota and outlying areas and for the purpose of receiving charitable donations — the public has donated around $36m to the East Gippsland region. The immediate priorities are to care for those who were adversely impacted by the fires and to work with emergency management agencies in preparation for bushfire season.

“One of the challenges faced by both MADRA and government agencies is that community-led recovery is unique for every town,” explains Lloyd. “At a minimum, it can be interpreted as communities identifying recovery gaps and proposing solutions based on local knowledge and priorities. This is the basis of our Recovery Plans, which we’re putting a lot of thought and effort into. But community-led recovery won’t work if it’s overlaid on the same old government regulations and processes designed for circumstances very different from the current unprecedented situation.”

Applying for grants is one example of a process that can cause headaches for community groups. “In normal circumstances, a community organisation might apply for one grant every two or three years,” she says. “We’re faced with applying for up to 20 or 30 grants across various levels of government. This is challenging for volunteers who don’t necessarily have the time, appropriate knowledge or the resources.”

Bushfire Recovery Victoria (BRV) was set up in early 2020 to link communities and government departments and to help cut through bureaucratic red tape. “There are bound to be challenges for a brand-new agency as it finds its feet,” says Lloyd. “Open and frank communication has been the key to working through issues. But I hope ongoing dialogue between communities and agencies such as BRV will expedite the recovery process.”

She recently saw one important step forward: “Resources such as grant writers and other specialists who can help us work through the recovery priorities and projects are now available to communities. Urgent projects are being assessed on a case-by-case basis.”

What recovery looks like

Lloyd believes that rebuilding will open up opportunities for making Mallacoota even more attractive to locals and visitors. “That could be as simple as building a ramp down to the beach so everyone can enjoy it,” she says. “We’re working with our local council as well as Parks Victoria with a view to building replacement infrastructure — not only to higher fire standards but also, where possible, so it accommodates people of all ages, stages and abilities.”

While many residents are still living in caravans as they wait to rebuild their homes, council planners have received 76 applications for new homes, with 57 permits approved. Plans for a new kindergarten are underway, including a survey of community needs, and the Lakeside Drive Walking Track boardwalk has been rebuilt.

More broadly, there’s the question of what a successful recovery would actually look like. “Are we aiming to restore the township to the way it was before the fires or to create a community that isn’t so reliant on tourism?” asks Tregellas.

“Like a lot of country towns, ours was dying even before the twin disasters of the fires and COVID-19. We had twice as many kids in school in the 1980s as we do now. The median age in 2001 was 45; now it’s 58. Almost 50 per cent of homes in Mallacoota are unoccupied, the newsagency closed last year and there’s a question mark hanging over one of our petrol stations.”

His personal view is that MADRA’s longer-term aim should be to turn the town around. “I’d like recovery to take us to the point where we’re once again a thriving community and young people have a reason and an opportunity to stay,” he says. “And, of course, we need to do this in a way that ensures Mallacoota is still the beautiful town that attracted people in the first place. No-one wants to see condominiums on the beach.”

Overcoming challenges

Meanwhile, the committee is having to work around the most basic problem: communication. “About 20 per cent of our community are without an internet connection,” says Lloyd. “We are in a huge black spot for the internet and our NBN infrastructure burned. Many people are struggling to get by and are still suffering trauma. COVID-19 has prevented us from holding community meetings, events, workshops... so we’re having to work back to front by drafting a plan and having people comment on it retrospectively, which is far from ideal.”

However, Pascoe is impressed by how MADRA is overcoming complex challenges. “I think the association was put together really well, with a lot of support from all sections of the community,” he says. “In Mallacoota, as with any small town, that can be difficult to achieve. Collaboration with governments and local council also requires goodwill and effort on both sides.”

Meanwhile, Tregellas is frustrated by the sense that the committee is having to reinvent the wheel. “This wasn’t the first disaster of its kind,” he says. “After the Black Saturday fires [in 2009], there was a royal commission. Kits were put together from various organisations... I assumed there would be a community recovery kit for us to follow, but it seems all that knowledge and insight has been lost.

“We need a more military approach, such as a standard operating procedure so that, if you have a disaster and you’re going to form a community recovery committee, you can refer to a step-by-step guide for the best and most efficient way of going about it.”

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content