Structural tax reform won't be a simple or cheap task, but experts agree it's time to start the conversation, writes Katie Walsh.

Recent history suggests a pattern when it comes to significant tax reform. First there is economic turmoil. Several years pass. The economy restores, then the nation embarks on bold change. The favoured examples are the early 1980s downturn preceding a broadening of the income tax base later that decade; and the “recession we had to have” in the early ’90s, with the introduction of the goods and services tax we were told we would never have.

The pattern could instil confidence that the COVID-19 crisis might trigger overdue tax reform, were it not for the uncomfortable truth that it was broken by the global financial crisis (GFC). Fiscal stimulus focused on household assistance and public infrastructure spending. The mining boom did the rest and structural tax reform never followed.

“These were the lost years of political leadership tumult and failure in Australia,” says Greg Smith, one of five eminent panellists on Australia’s Future Tax System Review commissioned by the Rudd government. Popularly known as the Henry Review, it was named for its chair, then Treasury secretary Ken Henry AC, now an ASX director.

COVID-19 has shown that the government can transcend the 24/7 media warpath and tackle notorious no-go zones — boosting cashflow and incomes via higher JobKeeper payments and briefly introducing free childcare. The 2020-21 Budget featured $31.6b in asset write-off and loss carry-back measures, plus $17.8b in fast-tracked personal income tax cuts. The question is whether Prime Minister Scott Morrison would consider spending political capital on big-ticket, long-term structural tax reform, particularly if it supports the Henry goal of boosting productivity and sustainable growth.

Tax reform milestones

- 1975 Asprey Review set three tax axioms: simplicity, efficiency, quality 1985–87 Capital gains tax, imputation credits introduced (Hawke/Keating)

- 1992 Superannuation guarantee introduced (Keating/Dawkins)

- 1998 Ralph Review on corporate tax (Howard/Costello)

- 2000 GST introduced (Howard/Costello), personal income/company tax cuts

- 2010 Henry Review (Rudd/Swan)

- 2011 Tax forum on carbon tax (Gillard/Swan)

- 2012 Minerals resource rent tax (Gillard/Swan)

- 2014 Minerals resource rent tax repealed (Abbott/Hockey)

- 2015 Tax White Paper (Abbott/Hockey) not completed

- 2015 Super changes, income/company tax rate changes

- 2015 Multinational anti-avoidance law: Tax Laws Amendment (Combating Multinational Tax Avoidance) Act 2015

- 2018 Diverted profit tax

Overdue for structural reform

Watching debate about tax reform can feel like watching an oft-screened sitcom episode. The plot is familiar, with its cherrypicked ideology, rich-versus-the-rest playbook and aversion to potentially offensive dialogue. The characters are well known, too: politicians with vague statements of good intentions, lobby groups with concrete demands and frustrated tax experts. Yet the show is no longer particularly comforting or funny. “We have a tax base that is creaking across the board,” says ASX Ltd director Heather Ridout AO MAICD. “We’ll all be much worse off if we don’t grapple with it.”

How we grapple with it is the challenge Australian governments at every level now face. But they face it alongside an unprecedented pandemic-fuelled global crisis. Can we afford to do anything? Can we afford not to?

“If we’re going to find a sustainable way out, we’ll have to embrace comprehensive tax reform — not just short-term revenue fixes, but real systemic changes,” says Ridout. “We need to invest in this to make the reforms sustainable. We’re all going to gain in the long term; however, we need to compensate for the regressive and inequitable aspects of any reform. We should be prepared to fairly compensate these groups.”

Ridout’s point is pertinent, yet often overlooked in the popularity contest of the political arena. The system as a whole, not each tax, must be equitable. What we need is leadership, a preparedness for give and take, a “package” approach.

Henry’s blueprint for change

A little more than a decade ago, Ridout was deeply involved in working out what that package might look like as one of the Henry Review panellists.

The resulting 1000-plus-page blueprint for a more efficient and effective tax and transfer system was released in May 2010. “It involved the top of the tree in every one of these tax areas, from all around the world,” she says. “We don’t need to do it again; we just need to update it for technology.”

The purpose of Henry was to concentrate the nation’s tax base in four areas: comprehensive personal income (placing most into a 35 per cent bracket), growth-oriented business income (including a 25 per cent corporate tax rate), natural resource and land rents (broad-based land tax and a 40 per cent tax on the super profits of resources) and consumption tax. No other tax should survive or exist unless it targets “social outcomes or market efficiency”, such as a switch to volumetric taxes on alcohol. The suite of 138 recommendations carried an estimated long-term GDP boost of three to four per cent. And therein lies the rub: this was a holistic set of measures, not isolated ideas.

Like Ridout, Smith is critical of the failure of successive federal governments to implement packages, and a tendency for divisive proposals.

The Rudd government chose the resources super profits tax as its showpiece to accompany the release of Henry, watering it down and linking it to a non-Henry superannuation guarantee boost, though it later fell under the axe of the Abbott government. The Turnbull government tried, but failed, to introduce a 25 per cent corporate rate, securing one for smaller businesses. Federal Labor, under Bill Shorten’s leadership, tried to win voters with a promise to overhaul franking credit refunds and negative gearing, only to lose at the ballot box.

“If you just say, ‘We have to take from A and give to B,’ well, that’s going to scare,” says Smith. “It has to bring together interests that are otherwise resistant.”

During a Treasury career spanning decades, Smith helped Paul Keating implement capital gains tax (CGT), fringe benefits tax and superannuation; headed Treasury’s secretariat to the Wallis Inquiry into banking; and sold the GST to Australians.

He warns that Australia must have radical reform at some point or else face a “moribund decade”. But the self-proclaimed “locked-down retiree”, heralded as one of the best tax brains in the country, apologises for his possibly “dispiriting” message that tax reform will have to wait even longer.

The cost of capital is at all-time lows, aggregate demand is short of economic potential, and deeper crises continue in areas such as the international movement of people. Tax systems are mainly structural rather than cyclical instruments of policy, and changes carry considerable adjustment costs — the government must prioritise its overall fiscal strategy to move beyond the initial crisis response to confidence building.

Similarly, the Grattan Institute has shifted its focus away from advocating for tax reform — backing a suite of tax measures ahead of the 2019 federal election, including halving the CGT discount to raise $4b, scrapping negative gearing to raise $2.1b, and tightening super concessions and reforming the GST to bring an extra $11b — towards the immediate responses to the crisis.

When the nation does tackle tax reform, Smith calls for a “much more creative and adventurous” approach to a package of measures. “Some parts of Henry have been passed over by history, while others were not fully developed due to restrictive terms of reference,” he says. Among the big-ticket items left out of the Henry Review were the GST (ruled out of its remit) and a carbon tax (sidelined because the carbon pollution reduction scheme — “expected to achieve given reduction targets in a cost-effective manner relative to other instruments” — was in motion).

States press the case

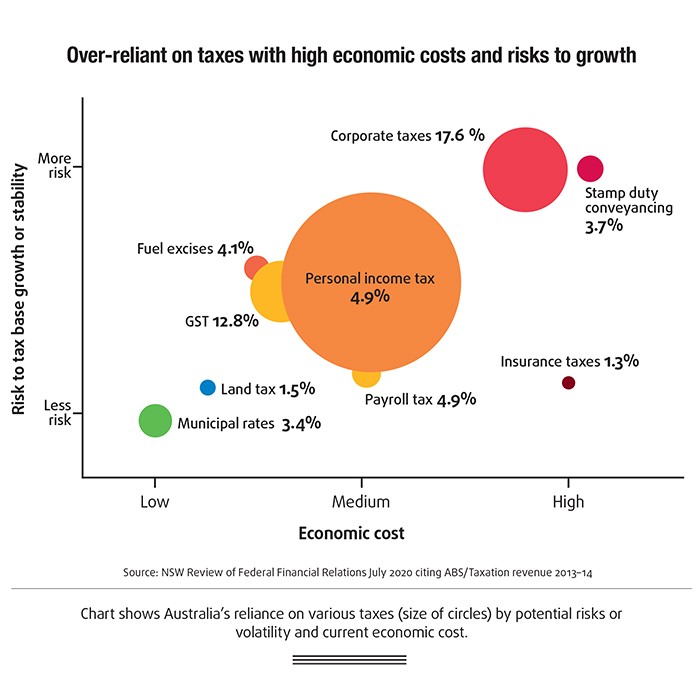

The states are pressing for bold changes as they sit on fragile revenue bases such as stamp duty, insurance tax and GST. The review of federal financial relations, commissioned by NSW Treasurer Dominic Perrottet and chaired by David Thodey AO FAICD, released its fast-tracked draft report in July.

Beyond the Henry-esque recommendations of replacing stamp duty and insurance taxes with broad-based land tax, reforming payroll tax nationwide and establishing fair distance-based road user charging, the panel called for the National Cabinet to become a permanent “body of equals”; cross-government consultations on lifting the rate of GST and/or expanding the base; and an untied share of income tax instead of tied grants. Australian states ceded income tax powers to the Commonwealth in 1942 as part of national wartime efforts — and they haven’t levied any since.

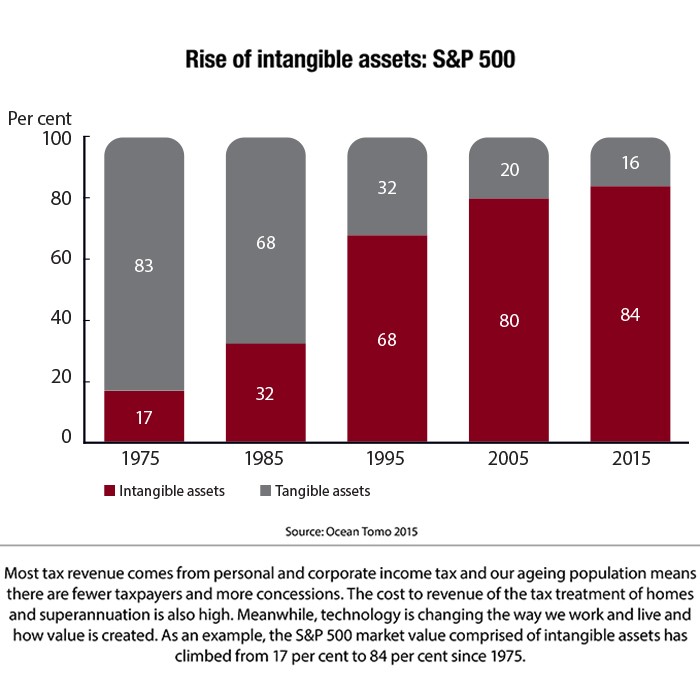

Among the review panellists is constitutional law expert Professor Anne Twomey and The University of Melbourne economics professor John Freebairn, who warns that productivity losses from the existing tax mix will only increase as COVID-19 changes the way we work and live.

Stamp duty, for example, not only increases business relocation costs and impedes labour mobility (Deloitte has estimated 340,000 transactions are forgone each year because of it), it also unfairly falls on those who buy or sell rather than on all property owners. A federal Treasury 2015 estimate put the welfare loss from transfer duties at 72 cents for every dollar raised, compared to a gain of 10 cents from land tax, which is also among the least risky in terms of growth and stability.

“There’s 50 to 80 cents a dollar,” says Freebairn. “I don’t believe BHP or any of those sorts of businesses have that on their shelf. That argument is going to be hard-fought, but it’s going to give a gutsy politician something to run with.”

Federal Treasurer Josh Frydenberg has pledged to work with state governments in their pursuit of tax reform, but emphasises that they have their own budgets. Yet the taxes on which states rely carry the highest costs to society and the economy as a whole. Royalties and insurance taxes carry a distortionary cost of almost 70 cents for every extra dollar raised. Payroll tax costs roughly 40 cents for each dollar.

The ACT began its 20-year transition from stamp duty to land tax in 2012. Larger states have resisted doing it alone and are heavily reliant on the Commonwealth-collected GST, which comprises 10–45 per cent of revenue.

The federal government has sounded the usual bugle against touching the GST, despite the rate sitting at roughly half the OECD average and the growth of proportional consumption on exempt items.

Health, education and childcare exemptions cost $4.55b, $4.85b and $1.63b, respectively, last year. Even if it was politically palatable, Freebairn says expanding the GST to cover these items is tricky. Governments are big providers, so it would churn a lot of money and encourage some to switch from the private sector. But he says “quite a bit” could be done by bringing in all food ($7.6b) and water, sewerage and drainage ($1.2b).

GST aside, Freebairn is pragmatically optimistic about state tax reform. “The states are in a real tax mess,” he says.

National challenge

At a federal level, Freebairn says the real mess is in capital and savings. As flagged by Henry, houses are exempt; dividends and interest are not. The family home and super accounts comprise more than half of all household assets and carry the heftiest price tags: almost $43b and $38b, respectively, in revenue forgone from CGT exemptions and concessional treatment in 2019 alone.

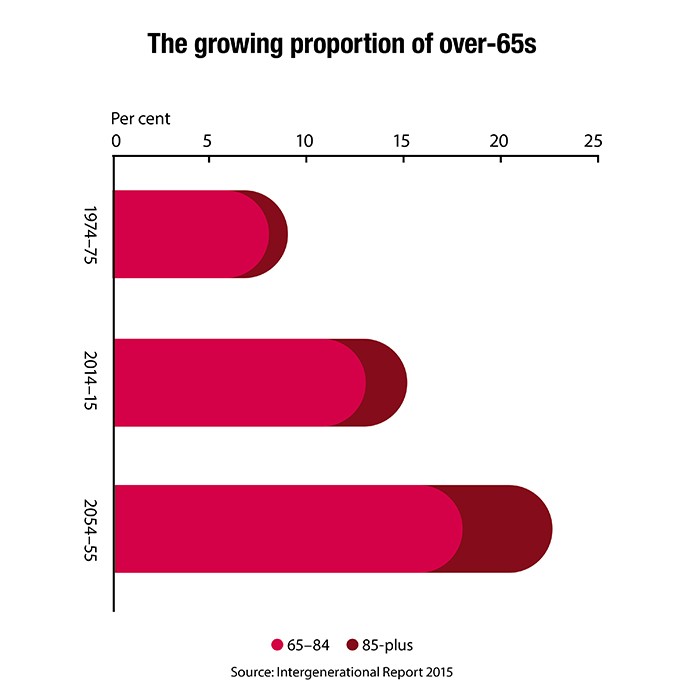

Henry backed a universal 40 per cent discount on interest, rent and capital gains, and taxing super contributions in the hands of taxpayers with an offset. Both carry the same inherent difficulty that has impeded change in the past — they essentially mean imposing tax on millions of Australians who have become accustomed to the status quo, including landowners and retirees. Which is why, for many, the missing piece is salesmanship.

Australian Industry Group head of policy Peter Burn says it’s vital to get business and community backing — a lesson learned from the GST, which almost cost former Prime Minister John Howard the 1998 election and felled John Hewson before him.

“You’re always going to make some people worse off in the short term. But if you can get trade-offs, help grow the pie and there are enough people supporting it, you can get there,” says Burn. “I don’t know what the ideal system is, but the Henry tax review went a long way to setting out all the bits and pieces. Some of the best tax minds in the country were involved in that review.”

Burn believes retirees may be more open to the merits of reducing superannuation concessions and franking credit refunds if they are given warning, as well as an explanation about how company tax cuts can offset the impact on the value of their assets.

A company tax cut extended to big business seems less likely in a COVID-19 world. Treasury has calculated that a 25 per cent rate would add one per cent to GDP, but notes it would largely benefit foreign shareholders. And there is debate about the effect of the United States’ cut from 35 per cent to 21 per cent in 2017.

Options that could raise money, such as mining — the Reserve Bank of Australia has said mining investment is “expected to remain relatively resilient in the near term” — and carbon taxes, are politically neutered. Behavioural levers, such as a tax on sugar, may have admirable causes but barely move the dial on debt.

Costs of concessions for homes and superannuation is high

Revenue forgone 2018-19

$42b full tax exemption on family home

$37.3b superannuation contributions/earnings

$9.4b discount for individuals & trusts

$7.6b GST food exemption

$4.8b GST education exemption

Source: Commonwealth Treasury Tax Benchmarks and Variations Statement 2019

World-class debate

Many seem to agree on the need to kickstart an open and honest debate on structural tax reform; a fresh look at Henry and beyond. Tax Institute director Andrew Mills says it is critical to pull together stakeholders — welfare, business, unions, professionals — for a back-to-basics discussion on key principles. For tax experts, those principles are written in stone, in the same way as tax laws for the ancient Etruscans:

- Simplicity — because the detail and complexity rife in tax laws and regulations creates a deadweight loss to society and businesses, our quasi tax collectors.

- Efficiency — you can’t tax your way to growth. The lower the cost to productivity, the better.

- Equity — because we live in a society.

These principles, however, can clash, further complicating an already complex scene.

Mills, who spent six years serving as an ATO Second Commissioner and formerly led tax behemoth Greenwoods & Herbert Smith Freehills, is helping the Tax Institute with its reform agenda and advocacy.

He says successful reforms in the past have done two things well: a packaged approach and a good communication plan involving fresh consultations and discussions with everything on the table. “This is where people need to start expanding their thinking away from the notion there’s going to be no cost to the budget,” he says.

Voice of truth

Greg Smith says he can understand why Australians have lost faith in the process. He calls for a different approach — one that breaks through the political cycle and gives people confidence that unaligned, non-vested interests are looking at the issues. “The problem in Australia is, we’ve got a government that doesn’t believe the public service has much to offer, which isn’t true,” he says.

During the pandemic, it has become normal to hear politicians refer to the advice of chief medical officers. During the summer bushfires, the go-to experts facing the cameras were fire commissioners. “These are the classic institutional experts you can turn to in a crisis,” says Smith. “There needs to be someone to turn to who people can trust. The key is that it’s clear from day one that everything you do is in the public interest.”

In September, the government appointed Dr Steven Kennedy PSM MAICD as Treasury Secretary, a return to having an economist and long-time public servant in the role. In May, RBA governor Philip Lowe told the Senate Select Committee on COVID-19 that there was an “opportunity to build on the cooperative spirit that is now serving us so well to push forward with reforms that would move us out of the shadows cast by the crisis”.

Political willpower

The Henry Review scripted the implications of doing nothing: disincentives to work, move, invest, save, adapt and grow. Even before COVID-19, says Ridout, “all those chickens were coming home to roost”.

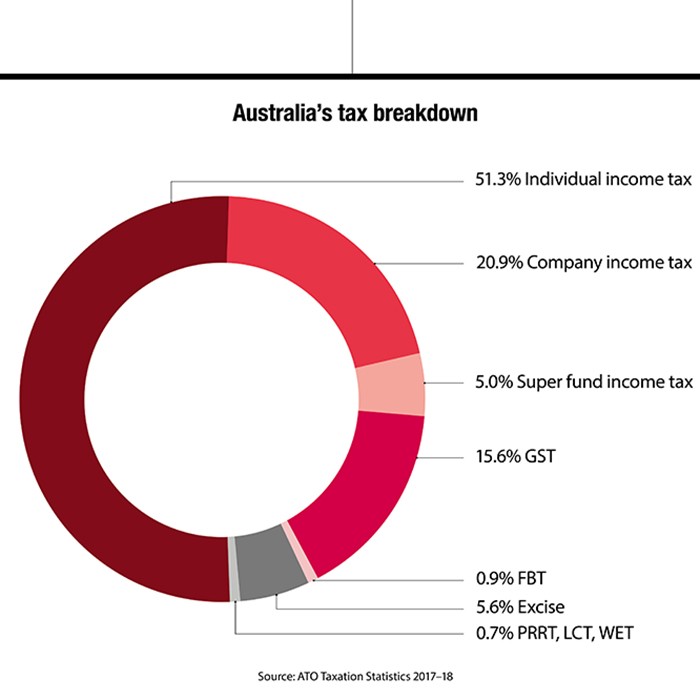

A decade ago, personal income tax accounted for 45 per cent of revenue; today, it is around 50 per cent and precariously tied to the fate of the economy. Company tax is constrained by borders in a global economy without any. Road user charges are based on fuel excise amid evolving technology. The rules themselves are so complex, Henry noted Australia’s use of tax agents was “second only to Italy’s”.

Ridout calls the 10 years since Henry the “decade of drift”. Halfway through that decade, Scott Morrison became Treasurer. The change in leadership brought the Tax White Paper process to an end, but in an interview with The Australian Financial Review, Morrison said he wanted to “talk more about what lower, simpler, fairer taxes actually deliver to people and why that helps them”. It’s the kind of straight-talking salesmanship many are pinning hopes on.

What to do?

There is growing consensus at a high level that we must start the conversation — but major tax reform might have to wait. Here are recommendations from recent reviews and analyses.

Grattan Institute — 2019

In 2019, the Grattan Institute released its Commonwealth Orange Book. Ideal policies included:

- Funding cuts to company and personal tax via more efficient land and broad-based consumption taxes.

- Halving the CGT discount to 25 per cent to raise $4b.

- Scrapping negative gearing to raise $2.1b.

- Tightening super concessions and reforming the GST to bring an extra $11b to coffers and directly compensate Australians in the lowest 20 per cent of income.

AICD — 2017

In 2017, the AICD released Governance of the Nation: A Blueprint for Growth, which listed fiscal sustainability — including comprehensive tax reform — as one of six areas to boost growth in Australia. The report called for:

- Comprehensive tax reform to deliver a more efficient, fair and growth-focused tax system.

- Reform of the GST, personal income tax rates, CGT discount, negative gearing and corporate tax rates are proposed, with incentives for reform of inefficient state taxes.

Treasury — 2015

In 2015, Treasury’s Tax White Paper Task Force found “widespread support for reform and dissatisfaction with the level of complexity in the tax system”. It received 870 submissions from organisations and individuals, and found:

- Support for cutting super concessions “but no clear agreement” on how.

- Support for broadening the GST base and/or increasing the rate as long as compensation is paid to those with low incomes.

- Majority support for lower personal income tax.

- Support for less concessional treatment of capital gains.

- Majority support for lower company tax rate.

- Overwhelming majority support for reduction of stamp duties.

- Tax savings consistently.

- Support for abolition of stamp duty and payroll tax.

Henry — 2010

- 138 recommendations to boost GDP 3–4 per cent long term.

- Scrap Medicare levy and offsets; tax-free threshold of $25,000; two marginal rates — 35 per cent up to $80,000 and 45 per cent above it (note: by 2024–25, personal income tax will levy at three rates: 19 per cent above the unchanged $18,200 tax-free threshold; 30 per cent above $45,000; and 45 per cent above $200,000).

- Tax super contributions at marginal rates with a flat offset.

- Apply a uniform 40 per cent discount across rents, interests and capital gains.

- Lower corporate tax rate to 25 per cent (note: rate lowered to 25 per cent for SMEs).

- Replace mineral royalties with a super profits tax of 40 per cent (watered-down version introduced without swap for royalties — later scrapped).

- Replace stamp duties and insurance taxes with broad-based land taxes.

- Business cashflow tax (alternative GST).

- National road transport agreement.

- Consider changes to imputation credits and a bequest tax (“controversial history”).

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content