Trust has multiple dimensions and rebuilding it requires different thinking and new board competencies. Insights from the recent KPMG-AICD Trust Survey helps directors make more sense of the changing landscape.

Organisations that want to start tackling the trust deficit need to start asking different questions, says Richard Boele, KPMG partner, Human Rights & Social Impact Services.

Writing in Maintaining the social licence to operate, where he shares the results of the recent KPMG-AICD Trust Survey of 600 directors, Boele identifies a fundamental contradiction with which many companies struggle. Contemporary businesses offer jobs, goods and services never before seen in human history, yet people increasingly distrust the companies that provide them. “This contradiction seems utterly confounding and begs the question ‘Why?’,” he says.

So how to build or regain trust? Boele writes that his recent experience with three different industries threatened by loss or potential loss of social licence showed boards need to start asking different questions.

While change is happening in organisational governance in Australia, the deepening level of distrust signals that a more significant change is needed and requires new board competencies, he writes.

“Boards can spend too much time asking, ‘How does this impact our business’ when they should be asking, ‘How does our business impact on people?’.”

Boele adds that the factors contributing to trust are more dynamic and interrelated than ever before, so boards must prioritise and focus on those that are most likely to impact their organisation and its stakeholders. To achieve this, they must rely on the effective escalation of data and reports from management on the issues that could undermine trust in the organisation.

About the Survey

The KPMG-AICD Trust Survey found trust is important to an organisation’s sustainability. Boards are looking to better understand and respond to the issues affecting their organisation’s trustworthiness. The survey covered directors from private businesses, NFPs, the public sector and listed companies.

The best way to get answers, he believes, is to start listening to the most vulnerable, marginalised or alternative voices potentially impacted by their organisation — the ones pointing us to the very issues we should be responding to.

Vulnerable stakeholders are the ones we have difficulty hearing because their voices are filtered out by layers of management. Vulnerable customers are sensitive to issues that could affect a wider group unless your business listens and appropriately responds to the harm it causes. If ignored, these issues eventually balloon into major news headlines that disappoint the public and ultimately erode their trust in institutions.

Issues affecting trust

Social licence is an important and powerful lens to frame trust. It acknowledges the active role that people and communities play in granting ongoing acceptance and approval of how companies conduct their business. Organisations can no longer view trust as an asset they can buy or re-build after a crisis, but one that must be earned and maintained on an ongoing basis.

A significant loss of trust is affecting all pillars of society, including government, business, media and NGOs. Boele writes that trust in organisations is increasingly becoming about people: those who lead organisations by making decisions and those who are impacted by those decisions.

Who matters?

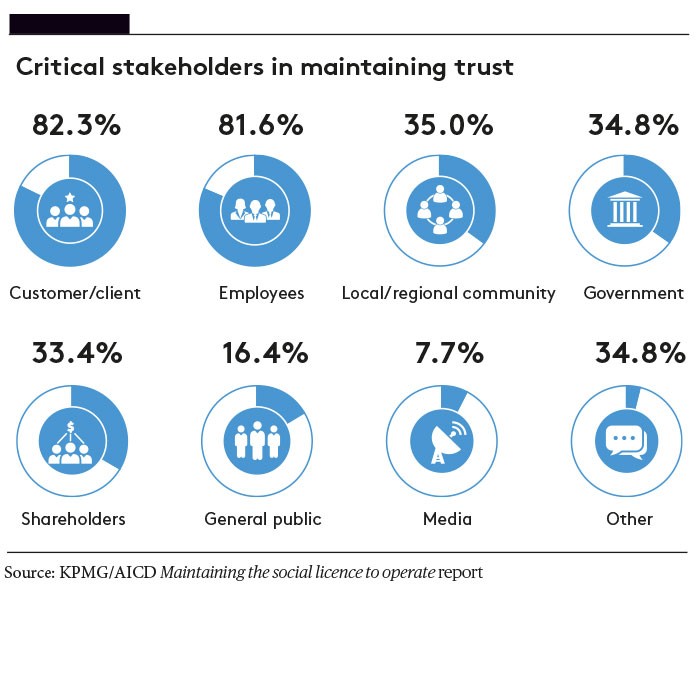

The survey asked AICD members to identify the three most critical stakeholders whose trust their organisation needed to maintain.

Boards overwhelmingly saw “clients or customers” and “employees” as the two most critical stakeholders (see chart). And echoing an important social licence issue, the local or regional community in which an organisation operates was selected as the third most critical stakeholder for Australian boards.

Role of internal culture

Although company directors feel a greater sense of responsibility to the wider communities they serve, “internal culture and practices” was voted by directors as the most critical issue relating to trust (with 74.1 per cent of directors selecting the issue among their top three issues) with customer satisfaction and product/service quality second.

The survey noted that “poor culture can lead individuals to make decisions and interact with external stakeholders in ways that may cause stakeholders to question the credibility, reliability and integrity of their organisation as a whole.”

Harnessing social media

Now that the community has access to information (and misinformation), enabled by social media and a 24-hour news cycle, an expanding plethora of issues are escalated to boardrooms.

“Whether it is a noisy construction site or child labour found in the supply chain — people will learn about these issues, talk about them, share them with the world and let organisations know what they think,” the survey report noted.

Recent activist campaigns against coal seam gas exploration in NSW and the Keystone Pipeline in the US showed how much public opinion and land ownership issues can impact major projects.

These cases demonstrated how stakeholder groups are successfully harnessing social media to amplify the awareness and reach of their campaigns to drive action, and to assign accountability for negative aspects. Interestingly, however, only 7.7 per cent of respondents perceive that the media is a key stakeholder for maintaining trust. The “general public” was seen as a critical stakeholder for over twice as many respondents (16.4 per cent). According to the survey, company directors are having to engage in increasingly diverse and complex topics that can affect trust in their organisation, sometimes well beyond the traditional business agendas.

“Comments by our survey respondents indicate that some of the skills now needed to meaningfully listen, engage and connect with stakeholders, are evolving beyond some boards’ comfort zones,” the report states.

Specifically, a minority of survey respondents feel that some of their peers lack the understanding and competence to address issues affecting trust, and believe that complacency and reluctance to engage can mean companies risk “taking [stakeholders’] trust for granted”.

Eight questions to consider

To introduce a social-licence lens to conversations on trust, directors should explore the following questions with their peers and management team:

- Do we have the appropriate internal capacity, expertise — and willingness — to actively and authentically listen to all stakeholders? How do we equip our people to better listen?

- What stakeholder voices are we hearing? Who is excluded from the conversation and how do we ensure they have the opportunity to participate?

- Do we have high-quality relationships with all stakeholders? How do we implicitly or explicitly prioritise our stakeholder relationships?

- What questions do stakeholders have about the legitimacy of our business model? Can we respond to these questions in an authentic manner?

- Do we consider the actual or potential impacts of our operations on vulnerable stakeholders before we make decisions that affect their lives?

- Do we have an authentic and meaningful social purpose? How do we bring this to life?

- What is the balance of positive and negative impacts on our stakeholders? Who bears the brunt of the negative impacts from our operations?

- Have we clearly articulated and understood what needs to change in our approach to stakeholder governance?

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content