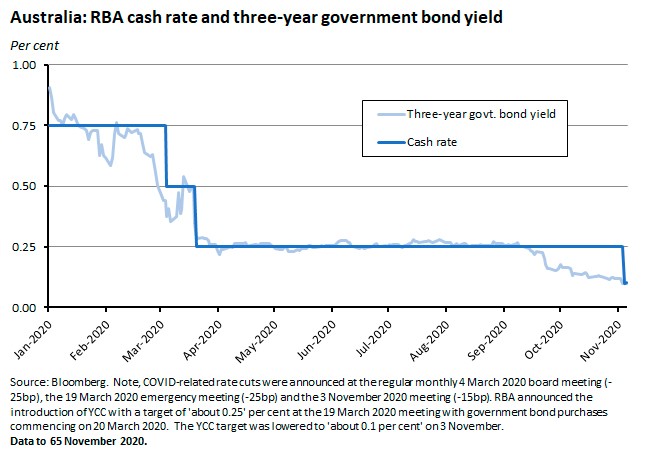

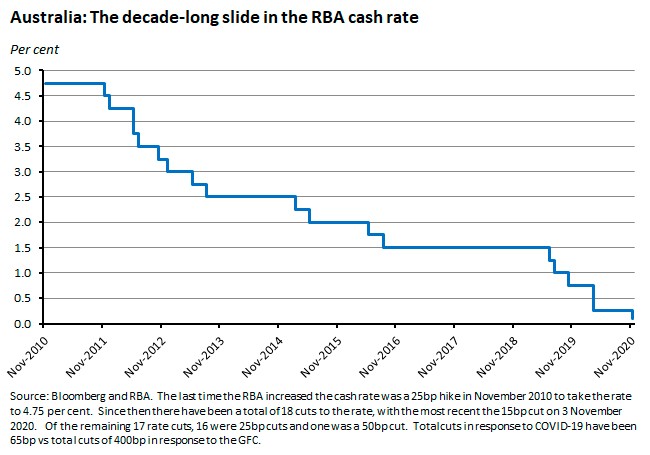

Inevitably, this week has been dominated by the closely contested US presidential election. But it has also been a busy week for Australian economic data. Top of the list was another historic day for the RBA, which on Tuesday took the cash rate and three-year yield curve target down to just 0.1 per cent, while promising $100 billion of government bond purchases over the next six months.

A big focus of the RBA’s messaging around its move was the labour market and this week’s Wage Price Index (WPI) brought the weakest growth in the 22-year history of the series. The latest set of payroll jobs numbers also showed employment going backwards over the past month. Retail turnover fell in September, but for Q3, overall volumes were up strongly, recording the biggest quarterly gain on record. Rock-bottom interest rates plus government stimulus continue to support the housing market, with CoreLogic’s national and combined capital cities home value indices rising in October, while dwelling approvals and new loans for housing both increased in September. ANZ job ads rose in October and have now pulled back about three quarters of their March-April fall. Australia reported a monthly trade surplus of $5.6 billion in September, even as news reports rolled in of more Chinese measures targeted at Australian exports. The latest composite Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) reading shows global business activity hit a 26-month high in October. US and eurozone GDP both rose strongly in the third quarter, although in each case real output remains below pre-pandemic levels.

Please note that Friday’s publication of the RBA November Statement on Monetary Policy comes too late for the Weekly’s publication schedule, but we’ll cover it next time.

This week’s readings include a report on the economics of climate change for Australia, new ABS data on internal migration, the relationship between mortality rates and economic downturns, the future of fiscal policy and rebuilding the global economy.

On this week's Dismal Science podcast we look at the results of the US election and what it means for the US economy, as well as the RBA decision.

You can subscribe and listen to The Dismal Science on your podcast player of choice at the links below.

Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Overcast | Stitcher

What I’ve been following in Australia . . .

What happened:

After its meeting on 3 November, the RBA announced a new set of policy measures designed ‘to support job creation and the recovery of the Australian economy from the pandemic’. The announcement was followed by a speech from the RBA governor which provided more detail around Tuesday’s decisions. The key components of the package were:

- A 15bp reduction in the cash rate target to 0.1 per cent from 0.25 per cent.

- A reduction in the target for the yield on the three-year Australian Government bond to ‘around 0.1 per cent’ from ‘around 0.25 per cent’. (Note that any bonds purchased in the future to support the RBA’s yield curve control (YCC) policy would be in addition to the new $100 billion bond purchase program described below.)

- A reduction in the interest rate on new drawings under the Term Funding Facility (TFF) to 0.1 per cent from 0.25 per cent.

- A reduction in the interest rate on Exchange Settlement balances to zero.

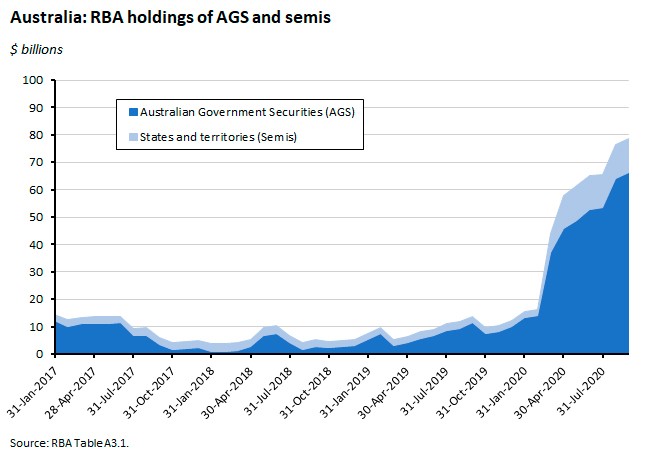

- The purchase of $100 billion of government bonds of maturities of around five to ten years over the next six months (although note that while the RBA will focus on buying bonds with maturities within this range, the governor said it could also buy other bonds, depending upon market conditions). Purchases under this program are expected to see 80 per cent allocated to Australian Government bonds (AGS) and 20 per cent to states and territories bonds (semis). The RBA expects to purchase around $5 billion of bonds per week under the program, excluding any purchases required by its YCC policy.

The RBA statement also summarised the central bank’s updated forecasts, which will be presented in more detail in the upcoming November Statement on Monetary Policy. It now expects positive GDP growth in the September quarter, despite the restrictions in Victoria, and in its central scenario GDP growth is expected to be around six per cent over the year to June 2021, up from the previous forecast of four per cent, before slowing to around four per cent in 2022. The unemployment rate is now projected to peak at a little below eight per cent, rather than the 10 per cent forecast previously. But note that even after these latest measures, the unemployment rate is still projected to be around six per cent by the end of 2022. As a result, the RBA thinks annual wage growth in each of the next two years will be less than two per cent. And that in turn contributes to its view that underlying inflation is likely to be just one per cent in 2021 and 1.5 per cent in 2022.

In line with its new approach to forward guidance, the RBA also promised that it would not increase the cash rate ‘until actual inflation is sustainably within the two to three per cent target range’, which it does not expect to be the case ‘for at least three years’.

The RBA said it would continue to review the size of the new bond purchase program and concluded by pledging that it was ‘prepared to do more if necessary.’

Why it matters:

The key contents of this week’s policy package had been expected by the markets with the cuts to the cash rate, YCC target and TFF rate all widely foreseen, while the introduction of outright quantitative easing had also been heavily tipped. Indeed, we’d noted back in September in the aftermath of a speech by Deputy Governor Guy Debelle, that more monetary easing was on its way.

Given that context, this week’s policy announcement was far from a surprise. But the fact that the RBA did a good job in managing expectations before delivering a much-anticipated policy shift should not take away from the historic nature of the 3 November Board meeting. It has left Australia with a cash rate that is barely above zero, a commitment to peg government bond yields out to three years at around the same rate, forward guidance to the effect that the cash rate will be left at this extremely low level for at least three years, and a $100 billion program of government bond purchases. The RBA hopes that the combined impact of these policy settings will be to further lower financing costs for borrowers, contribute to ‘a lower exchange rate than otherwise’ and help support both asset prices and balance sheets.

Why act now and not before (or alternatively, why not wait before doing more?) Governor Lowe set out two justifications for the timing of the new package. First, he made the point that the passage of time had clarified the nature of the pandemic’s impact on the economy, particularly with regard to the labour market, where he noted that a ‘sharp bounce-back in jobs is unlikely and it will take time to return to where we were before the pandemic. We have responded to this clearer picture today.’ And second, he repeated a point made in previous speeches that ‘monetary easing is likely to get more traction today than it would have when widespread restrictions were in place.’

The Governor’s speech made several additional points that are also worth noting here.

- One interesting aspect of the RBA’s expanded policy settings is the combination of price and quantity targets, with a price-based target at the shorter end of the yield curve (the YCC policy announced in the March package earlier this year) now joined by a quantity target at the longer end of the yield curve (the $100 billion of bond purchases aimed at the five-to-ten year segment). The reason for adding QE to YCC appears to be in response to a recognition that a policy based solely on the former has led Australia to have higher long-term bond yields than elsewhere and that these ‘higher bond yields have added to the attractiveness of Australian dollar assets and this has put some upward pressure on the exchange rate.’ The plan is that the portfolio rebalancing triggered by QE (that is, when investors in the private sector adjust their portfolios by using the proceeds from their bond sales to the central bank to buy different assets) will not only influence other interest rates in the economy, but will also affect the dollar.

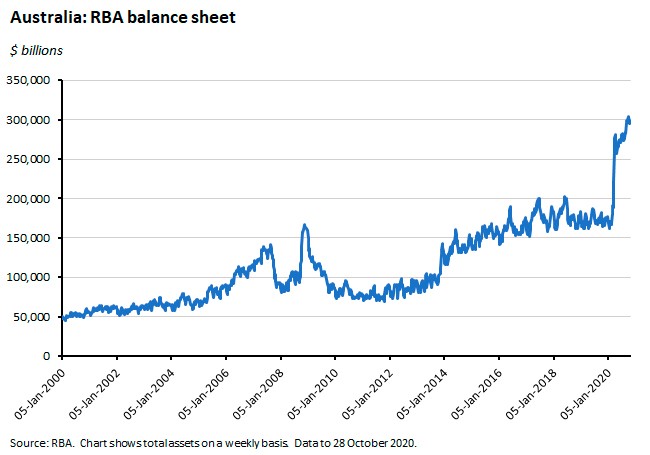

- The speech also reinforced the point that under this new policy regime, central bank watchers will have to spend more time looking at the size of the balance sheet and less time looking at the cash rate. With 0.1 per cent now the new effective lower bound and with Lowe sticking to his mantra that the RBA has no appetite for negative rates, interest rate policy is now done. Instead, as a result of the new asset purchases, the governor estimates that by the middle of next year, the RBA’s balance sheet will have almost tripled relative to the start of this year, assuming that the funds currently available under the TFF are also drawn upon.

- But is interest rate policy really done? Lowe actually did leave room for the RBA to pursue a policy of negative rates, noting that to some extent it was hostage to developments elsewhere (particularly at the Fed). So just as aggressive asset buying by other central banks has forced the RBA into QE, it’s also possible that a policy of negative interest rates that is adopted by a wider range of central banks than is currently the case could also force the RBA to follow, regardless of its dislike of the policy.

- Lowe was once again at pains to stress that the RBA was not directly financing the government budget, emphasising what he sees as a critical distinction ‘between providing finance and affecting the cost of that finance’. How important that distinction is in practice is arguably at least a bit debatable, but either way the RBA is set to become a much more important player in the government bond market. The current bond purchase plan is set to see the central bank own about 15 per cent of Australian Government Securities (AGS) on issue.

- An emphasis on the labour market has been a feature of RBA speeches well before COVID-19, but that emphasis has grown markedly in recent months following the pandemic-driven rise in joblessness. Governor Lowe was at pains to point out that ‘the inflation target remains the cornerstone of Australia's monetary framework’. But, he continued, ‘the priority over the next couple of years is jobs, with inflation risks remaining low. The RBA has a broad legislative mandate for price stability, full employment and the economic welfare of the Australian people. Today's decision reflects that broad mandate’.

- What about any risks associated with the new approach? The RBA’s view is that these are relatively insignificant relative to the need to focus on labour market repair. In his speech, Lowe noted that ‘low rates can encourage some additional risk-taking, as investors search for yield...low deposit rates can create difficulties for some people…But the Board judged that the bigger risk at the moment was the threat to our economy and to balance sheets from an extended period of high unemployment’.

One last point. Despite this aggressive monetary response, plus the fiscal stimulus announced in the 6 October budget, and despite an upgrade to its own short-term outlook for the economy, the RBA still thinks that ‘it is highly likely that the recovery will be uneven and drawn out. In particular, we face the prospect of a long period of higher unemployment and underemployment than we have become used to’.

What happened:

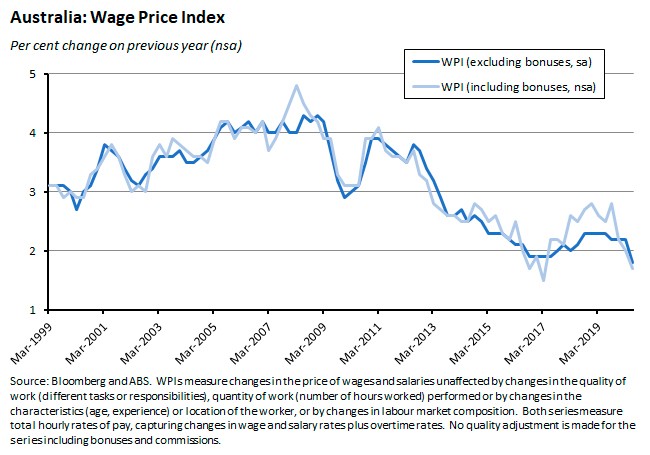

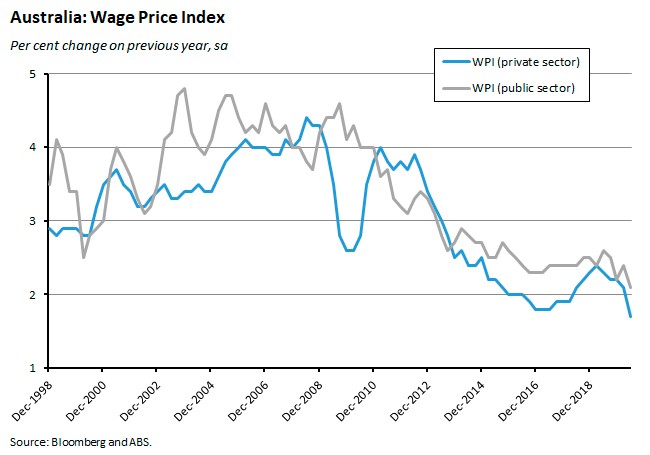

The ABS said the Wage Price Index (WPI) rose 0.2 per cent over the quarter in the June quarter of this year (seasonally adjusted) and was up 1.8 per cent in annual terms.

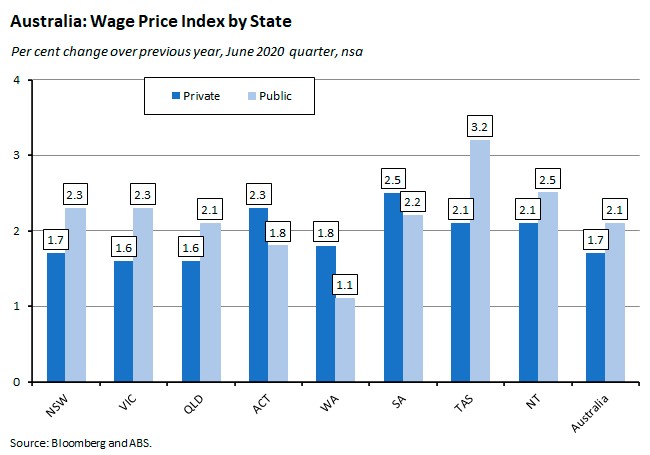

The private sector WPI rose 0.1 per cent quarter-on-quarter (seasonally adjusted) and 1.7 per cent year-on-year, while the public sector WPI was up 0.6 per cent over the quarter (seasonally adjusted) and 2.1 per cent over the year.

All states and territories saw their WPI increase over the June quarter, with the exception of Victoria, which experienced a quarterly decline of 0.1 per cent. South Australia (up 0.4 per cent) enjoyed the strongest quarterly rise. In annual terms, the fastest growth was in South Australia and Tasmania and the most modest growth was in Western Australia.

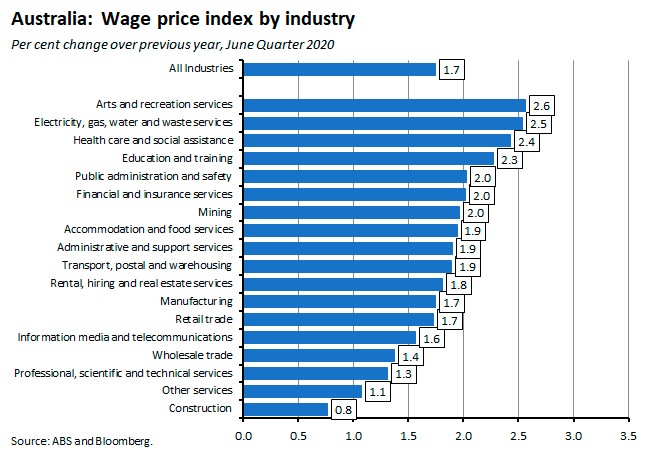

By industry, there were quarterly falls in the WPI for other services, professional, scientific and technical services, rental hiring and real estate services, accommodation and food services, wholesale trade and construction, with other sectors enjoying a rise. The biggest quarterly decline was in other services (down 0.9 per cent) and the biggest increase in electricity, gas, water and waste services (up 0.6 per cent).

In annual terms, the rate of growth in the WPI ranged from a low of 0.8 per cent in construction to a high of 2.6 per cent in arts and recreational services.

Why it matters:

The June quarter result showed a pandemic-damaged labour market delivering an extremely weak wage outcome. June’s 0.2 per cent seasonally adjusted rise in the WPI was the smallest quarterly increase since the series began in Q3:1997, while the annual print of 1.8 per cent was again the weakest result in the 22-year history of the series.

Also notable was the fact that private sector wages fell 0.1 per cent over the quarter in original terms, marking the first negative result in the history of the WPI. According to the ABS, this decline mainly reflected a number of large wage reductions across senior executive and higher paid jobs.

What happened:

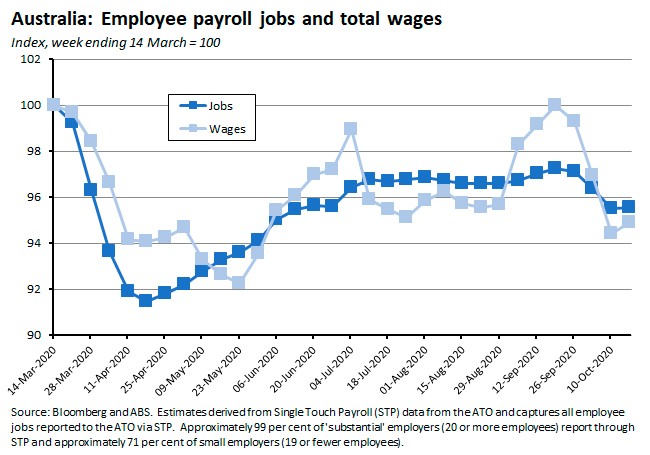

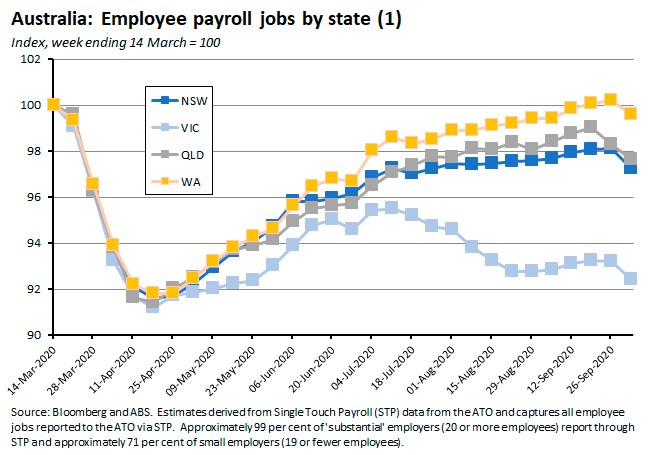

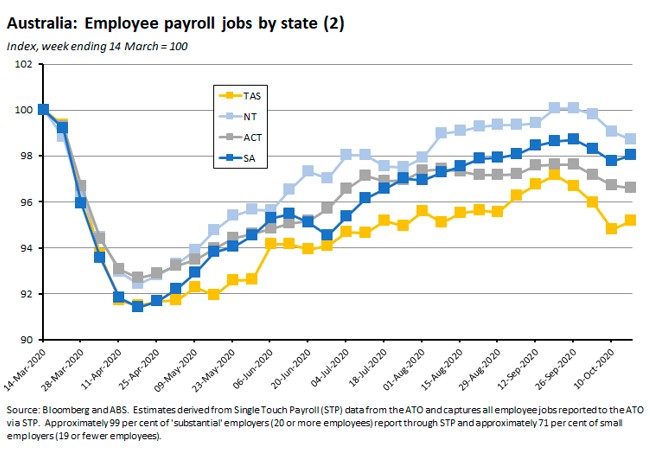

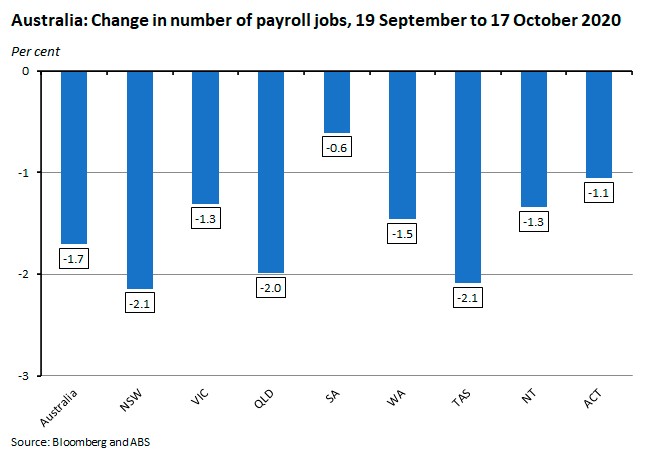

The ABS reported that between the week ending 14 March and the week ending 17 October 2020, the number of payroll jobs decreased by 4.4 per cent, while total wages paid decreased by 5.1 per cent. As of 17 October, there were approximately 470,000 fewer payroll jobs than there were on 14 March 2020. Over the most recent period covered by the data, between the week ending 3 October 2020 and the week ending 17 October 2020 the number of payroll jobs fell by 0.8 per cent, compared to a decrease of 0.9 per cent in the previous fortnight.

By state, since the week ending 14 March 2020, the largest changes across states and territories include an eight per cent decline in payroll jobs in Victoria and a 4.8 per cent fall in Tasmania. Between the week ending 3 October 2020 and the week ending 17 October 2020 payroll jobs declined by 1.3 per cent in New South Wales, 1.1 per cent in the NT and one per cent in Western Australia.

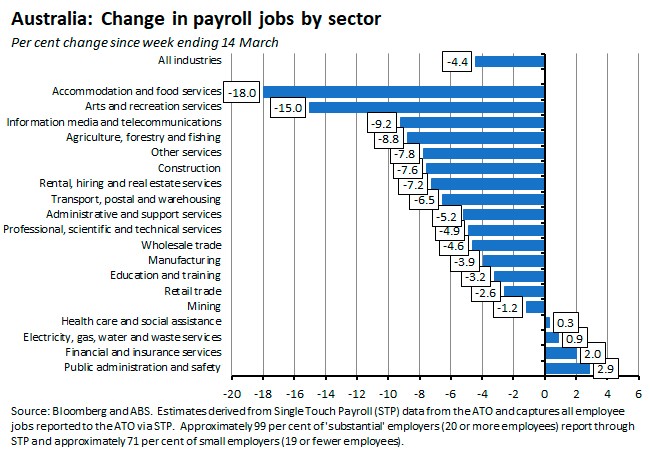

By industry, since the week ending 14 March 2020, the largest changes in payroll job numbers have been falls in accommodation and food services (down 18 per cent), in arts and recreation services (down 15 per cent) and in information, media and telecommunications (down 9.2 per cent). Since 3 October, the biggest declines have been in agriculture, forestry and fishing (down 4.1 per cent), construction (down 3.6 per cent) and other services (down 3.3 per cent).

Why it matters:

We noted a fortnight ago that the payroll jobs series was signalling a disappointing labour market performance, and this latest set of numbers continues to tell the same story of a stalled labour market recovery. Over the past month, total payroll jobs are down 1.7 per cent across Australia and have fallen across every state, with the largest declines in New South Wales and Tasmania (both down 2.1 per cent). It’s possible that some of this decline may reflect the impact of the 28 September introduction of the modified eligibility test for JobKeeper.

That said, however, as usual it’s very important to caveat the payroll numbers by remembering that this is a new experimental series, it is not seasonally adjusted (which means that it wouldn’t correct for any seasonal weakness in the labour market), and it is subject to large revisions. The regular monthly labour force data will give us the chance to assess how much of the recent run of weak results are signal vs noise.

What happened:

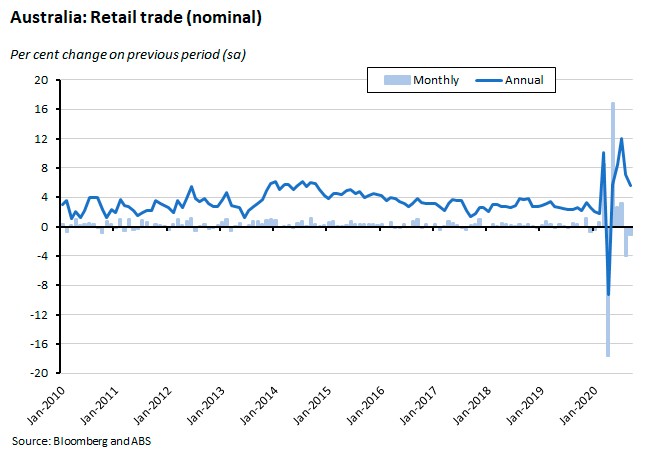

According to the ABS, retail turnover fell 1.1 per cent over the month (seasonally adjusted) in September, but was up 5.6 per cent over the year.

By industry, there were monthly declines in turnover for food retailing, for household retailing, for clothing, footwear and personal accessory retailing, and for other retailing. On the other hand, there were increases for cafes, restaurants and takeaway food services and for department stores. In dollar terms, turnover in food retailing, household retailing and other retailing remains elevated relative to pre-pandemic levels.

By state, only the NT saw an increase in turnover over the month (up 4.3 per cent in seasonally adjusted terms). Elsewhere, monthly turnover fell in New South Wales (down 0.9 per cent), Queensland (down 1.2 per cent), Western Australia (down 1.7 per cent), South Australia (down 2.9 per cent), Victoria (down 0.4 per cent), the ACT (down 2.4 per cent), and Tasmania (down two per cent).

The share of online sales in retail turnover eased to 10.6 per cent in September from 11 per in August, but still remains well up on the 6.6 per cent share it held in September 2019.

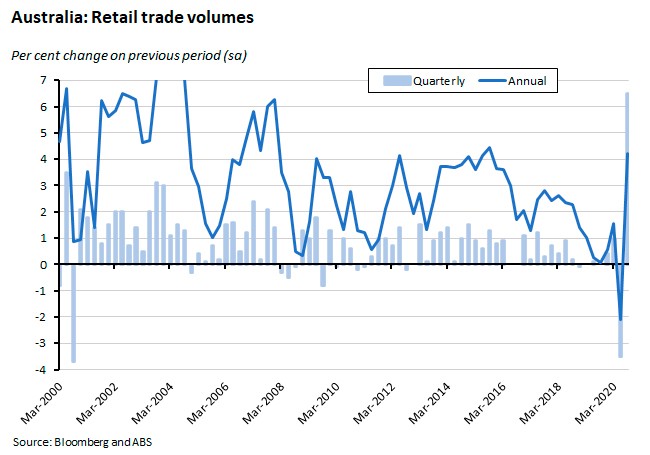

In volume terms, quarterly turnover rose 6.5 per cent (seasonally adjusted) in the September quarter 2020 and was up 4.2 per cent over the year. The Bureau said the quarterly rise was driven by a recovery in industries that had suffered sharp falls in the June quarter, along with continued strength in industries such as food retailing, other retailing and household goods. In particular, there were strong rises for cafes, restaurants and takeaway food services (up 28.1 per cent), and clothing, footwear and personal accessory retailing (up 35.5 per cent).

Why it matters:

The 1.1 per cent actual monthly decline in September was a little smaller than the 1.5 per cent decline given by the preliminary release and although the total value of retail turnover continues to fall back from July’s record high, it still remains elevated relative to pre-pandemic levels, supported by higher spending on food, household goods and other retailing.

The Q3 volume numbers showed a very strong recovery in the third quarter after Q2’s 3.5 per cent decline, with the 6.5 per cent rise reported this week the biggest quarterly increase on record. That should be good news for the household consumption component of September quarter GDP, with retail sales typically accounting for about one third of overall consumer spending.

What happened:

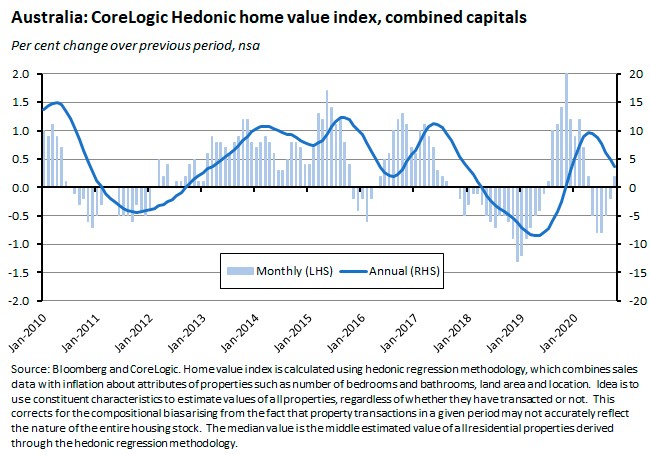

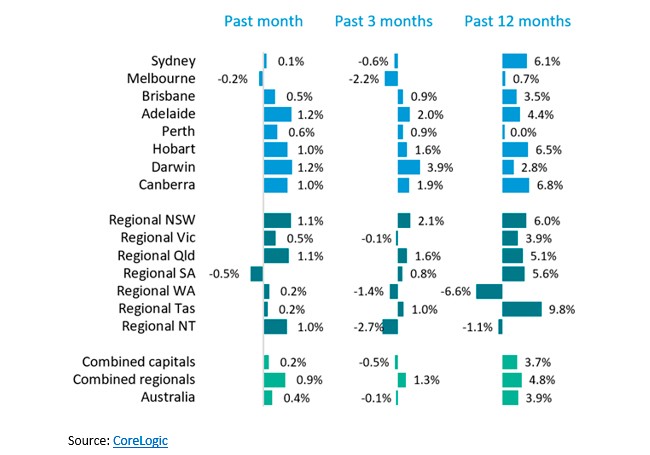

CoreLogic’s combined capitals dwelling values index rose 0.2 per cent in October and was up 3.7 per cent in annual terms. The national price index rose 0.2 per cent month-on-month and 3.9 per cent over the year. CoreLogic also pointed to a divergence between house and unit market performance, with rising home values in October offsetting a decline in unit values.

Dwelling values rose over October in every capital city with the exception of Melbourne, where values slipped 0.2 per cent. The largest monthly gains were in Adelaide and Darwin (each up 1.2 per cent over the month, followed by Hobart and Canberra (both enjoying a one per cent rise). Source: CoreLogic

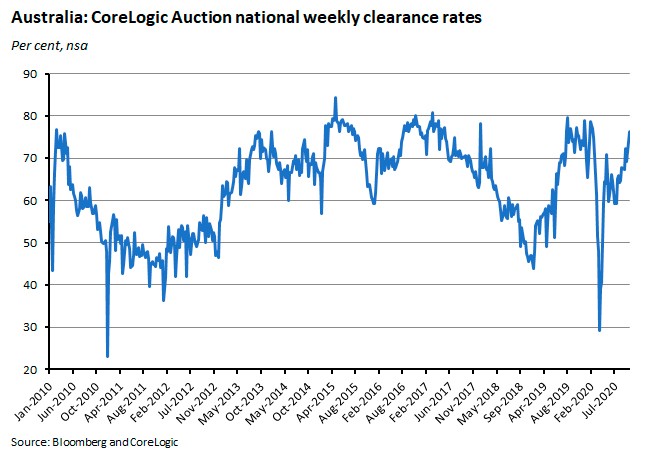

The national weekly auction clearance rate rose to more than 76 per cent in late October, the highest level since March this year.

Why it matters:

CoreLogic’s national and combined capitals indices had fallen for five consecutive months before October’s rise, and with the increase in prices broad-based (even in the case of Melbourne, the only city to see prices fall in the month, the size of the monthly fall was the smallest suffered since April) suggests the start of a recovery in the housing market – at least for houses as opposed to units. That’s also consistent with other housing market indicators, including a rising volume of home sales in October, stronger auction clearance rates and an increase in real estate agent activity. And it matches positive September results for building approvals and loan commitments (see next two stories). Very low interest rates and improving sentiment underpin the turnaround, along with some assistance from government policy measures such as the HomeBuilder grant.

What happened:

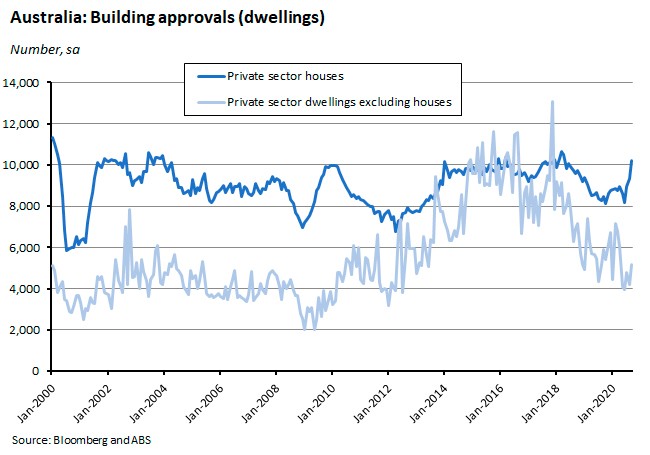

The ABS reported that the seasonally adjusted estimate for total dwellings approved rose 15.4 per cent in September, to be up 8.8 per cent over the year. Approvals for private sector dwellings excluding houses rose 23.4 per cent over the month, but were still down 12.1 per cent relative to September 2019 levels, while approvals for private sector houses rose 9.7 per month-on-month and 20.7 per cent over the year.

Dwelling approvals rose across the states, with large increases in Western Australia (42.6 per cent), South Australia (28.3 per cent), Queensland (19.3 per cent) and Tasmania (18.8 per cent) and more modest increases in Victoria (12.4 per cent) and New South Wales (4.6 per cent).

Why it matters:

September’s rise in approvals was mainly driven by a big monthly jump in approvals for private sector dwellings excluding houses, although in absolute terms these remain well down on the corresponding month in 2019. While the rise in approvals for private sector houses was more modest this month than last, it also marked a third consecutive monthly rise and puts the level of approvals well up over the year.

The ABS noted that the results indicated continued demand for detached housing following the relaxation of COVID-19 restrictions in most states and territories, a finding which is also consistent with the movements in dwelling values reported by CoreLogic and discussed above.

What happened:

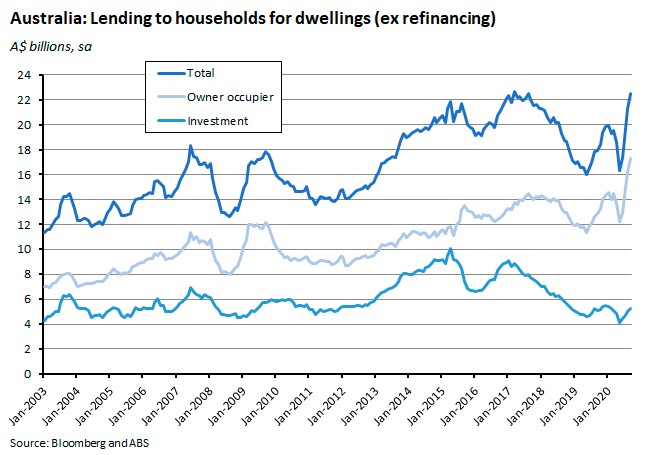

In seasonally adjusted terms, new monthly loan commitments in September rose 5.9 per cent for housing, 8.5 per cent for personal fixed terms loans and 57.2 per cent for business construction (typically a volatile series).

According to the ABS, while the total value of loans for housing was up 5.9 per cent over the month and 25.5 per cent over the year, loans for owner occupiers were up six per cent over the month and 33.8 per cent over the year while investor loans were up 5.2 per cent over the month and 4.2 per cent over the year.

The Bureau said the value of owner occupier home loan commitments rose in all states except Victoria and Tasmania in September. Victorian owner occupier home loan commitments fell 8.8 per cent in seasonally adjusted terms, reflecting decreased housing market activity in July and August after COVID-19 related stage 3 and stage 4 restrictions were imposed.

Why it matters:

Commitments for owner occupier housing loans commitments have now risen to historically high levels, supported by extremely low interest rates plus the impact of government incentives. The ABS said roughly half of the rise in September’s owner occupier commitments was for the construction of new dwellings, which were up by more than 25 per cent following a similarly strong (more than 19 per cent) increase in August.

What happened:

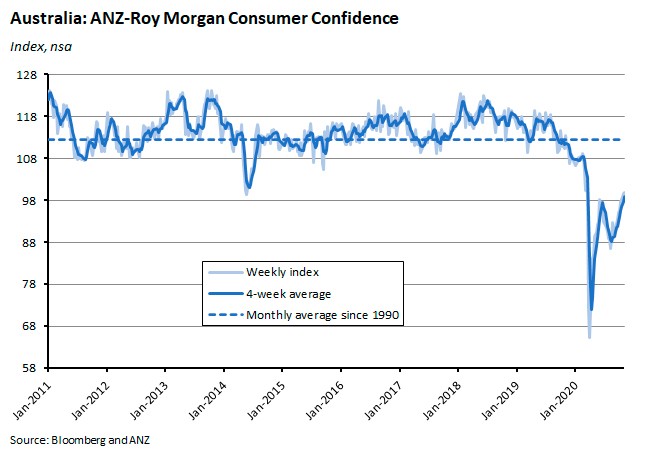

The ANZ Roy Morgan consumer confidence index rose 0.2 per cent to an index value of 99.1 on October 31/November 1.

The modest overall increase reflected a strong gain in the ‘current economic conditions’ subindex and smaller gains in the ‘future economic conditions’ and ‘future financial conditions’ subindices that were just large enough to slightly more than offset falls in the ‘current economic conditions’ and ‘time to buy a household item’ components.

Why it matters:

Although sentiment only edged a little bit higher, this marks nine consecutive weeks of rising consumer confidence. The weekly index is now at its highest level since March 14/15, which was when it last hit a ‘neutral’ reading of 100.

The details, however, do sound one note of caution, with a more than six per cent decline in the ‘current financial conditions’ subindex, the biggest drop in this component seen since the big collapse in confidence back in March. ANZ suggested that this weakness could reflect the impact of cutbacks to payments under the JobKeeper and JobSeeker programs.

What happened:

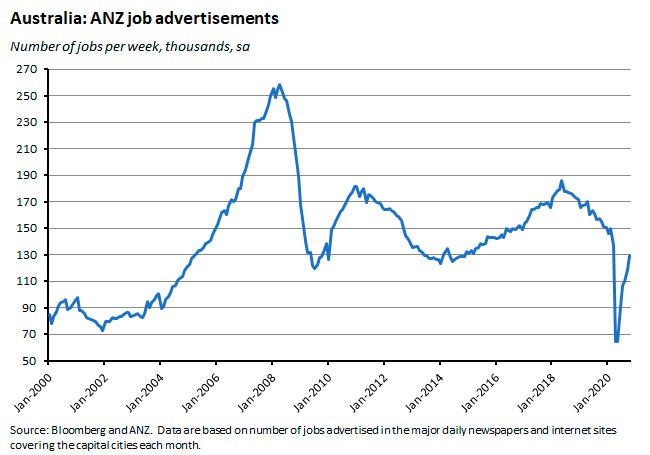

ANZ Job Ads rose 9.4 per cent over the month in October, although they were still down 16.2 per cent over the year.

Why it matters:

Job Ads have now clawed back more than 75 per cent of the fall they suffered in March and April this year. According to SEEK, one of the sources of the underlying data, job ads are now above pre-pandemic levels in most states, but there is still a significant gap in the ACT, New South Wales and Victoria.

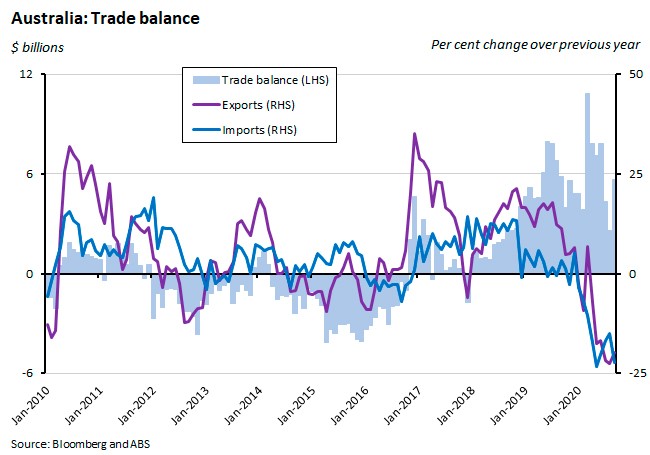

What happened:

Australia’s monthly trade balance recorded a surplus of $5.6 billion in September (seasonally adjusted) which was up $3 billion on the August result. The ABS reported that exports of goods and services rose four per cent over the month, while imports of goods and services fell six per cent.

Why it matters:

Following two months of narrowing trade surpluses, September’s result showed a reversal of the recent trend as exports and imports headed in opposite directions.

Arguably more important than the monthly trade numbers, however, has been the continued flow of stories about obstacles to Australian exports to China. The past week has seen several reports of Beijing introducing new restrictions on bilateral trade that could now impact a list of goods including wine, copper, barley, coal, sugar, timber and lobster.

What happened:

Last Friday, the ABS published the 2019-20 Australian System of National Accounts. Key points included:

- Real GDP in 2019-20 fell 0.3 per cent while real GDP per capita contracted by 1.7 per cent. But real net national disposable income rose 0.9 per cent, mainly thanks to a 0.8 per cent increase in the terms of trade. Nominal GDP was up by just 1.7 per cent.

- Household consumption fell three per cent, the first annual decline in recorded history. As a share of GDP, household consumption fell to 53.7 per cent, the lowest share since 1973-74.

- The household saving ratio jumped to 10.3 per cent, its highest rate in 34 years.

- Investment as a share of GDP fell to 22.5 per cent, its lowest level since measurement began in 1959-60.

- Australia’s largest industries by share of gross value added (GVA) were mining (11.1 per cent), financial and insurance services (8.9 per cent) and construction and health care and social assistance services (both 7.7 per cent), followed by professional, scientific and technical services (7.6 per cent).

- Labour productivity rose 0.5 per cent over the year as a fall in hours worked outstripped the overall fall in GVA, while unit labour costs fell 0.9 per cent.

- The compensation of employees (COE) share of total factor income fell to 51.7 per cent, the lowest share since 1963-64. The profits share of total factor income rose to 29.4 per cent, the highest share in recorded history.

- After 46 consecutive years of net external borrowing, Australia became a net lender to the rest of the world.

Why it matters:

2019-20 marked the end of Australia’s run of 28 consecutive years of recession-free economic growth and was a landmark year with several major indicators hitting record highs or lows.

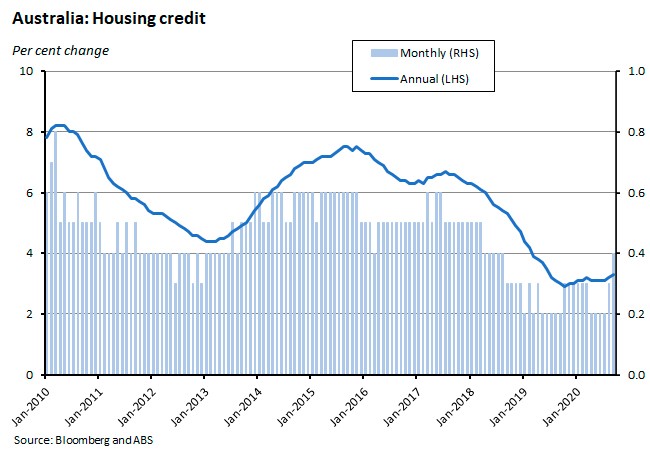

What happened:

Last Friday also saw the RBA publish data on Australia’s financial aggregates for September. Total credit growth was 0.1 per cent over the month and two per cent over the year. Housing credit was up 0.4 per cent month-on-month and 3.3 per cent over the year, led by 0.5 per cent monthly growth in credit to owner occupiers, as well as a more modest 0.1 per cent monthly increase for investors.

Personal credit fell 0.8 per cent over the month in September and was 12.5 per cent down relative to September 2019. Credit to business contracted 0.3 per cent over the month but was still up two per cent over the year.

Why it matters:

Credit growth remains subdued with activity concentrated in the housing sector. Credit to the business sectors has now fallen for five consecutive months, although this was the smallest rate of decline to date, while personal credit has been falling month-on-month since June 2018.

. . . and what I’ve been following in the global economy

What happened:

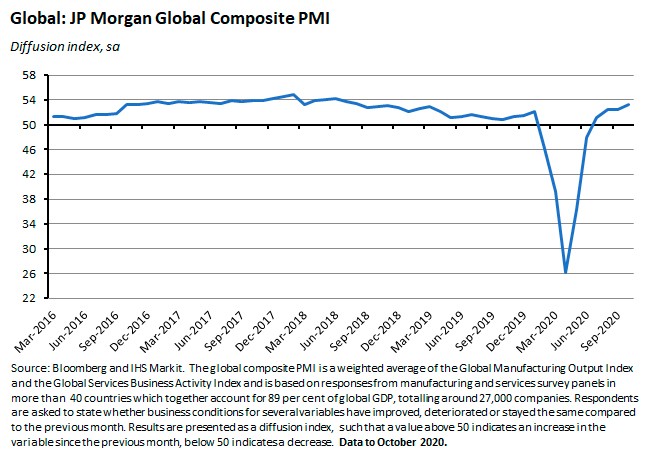

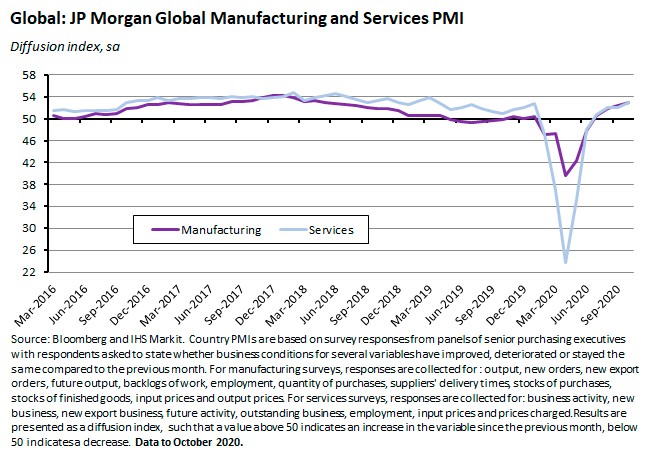

The JP Morgan Global Composite PMI rose to 53.3 in October from 52.5 in September.

Five of the six subsectors that comprise the overall index rose in October, with solid increases for business services, financial services, intermediate goods and investment goods. Consumer goods producers also reported a positive result, although it was the weakest reading for the sector in four months. Consumer services output contracted for a ninth consecutive month.

Overall, the global busines services index rose to 52.9 in October from a reading of 52 in September, while the JPM Manufacturing PMI rose to 53 in October from 52.4 last month.

Why it matters:

The composite PMI rose for a fourth consecutive month in October to hit a 26-month high, signalling the fastest rise in global activity in more than two years. This tells us that the recovery in global activity that ran through the third quarter of this year continued into the first month of Q4:2020. The global business services index is now at a 19-month high, while the global manufacturing PMI is at a 29-month high in October.

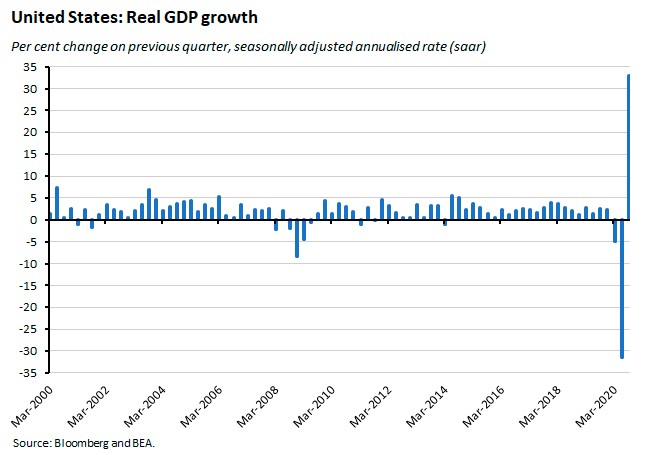

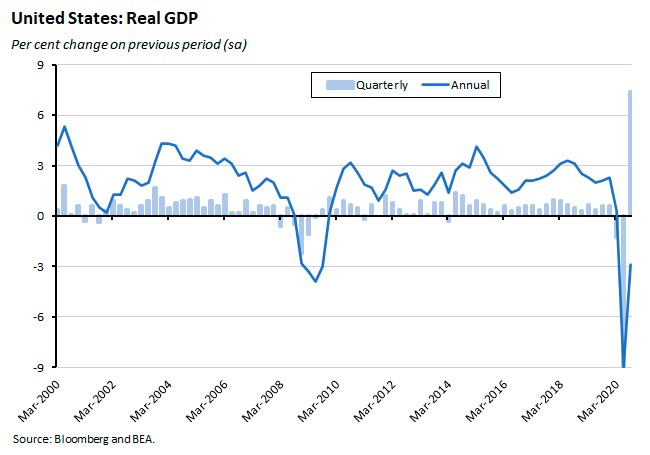

What happened:

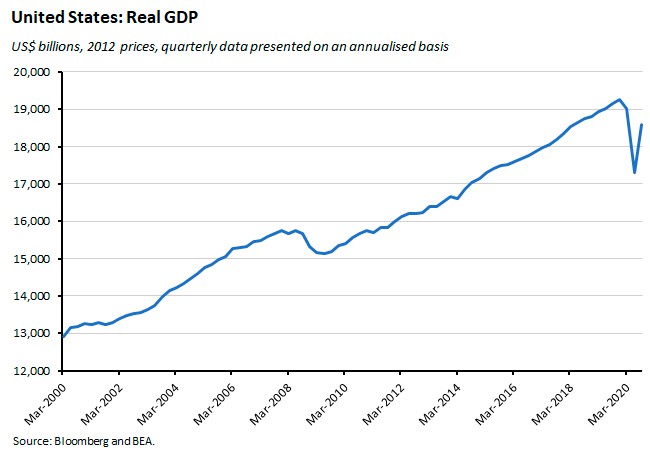

According to the ‘advance’ estimate from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), US GDP rose at a seasonally-adjusted annualised rate (saar) of 33.1 per cent in the September quarter of 2020, following on from the June quarter’s dramatic 31.4 per cent drop. The past two quarters in the United States have now witnessed both a record decline and a record increase.

Note that the US approach of presenting data on a saar basis makes the shift look outsized relative to the GDP reports of other economies. If the numbers were instead reported as a more standard quarter on quarter growth rise, then the data show Q3 GDP rising by 7.4 per cent over the quarter following a nine per cent decline in Q2.

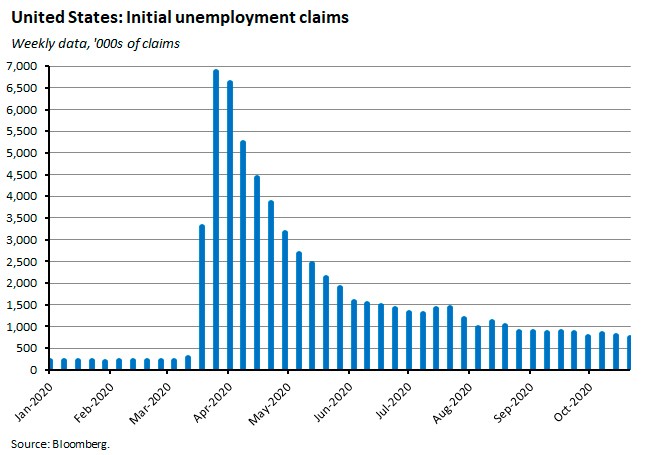

Other recent economic indicators suggest that US third quarter recovery has continued into the final quarter of this year. For example, initial jobless claims fell to 751,000 in the week through 24 October, the lowest level since mid-March. But that still leaves claims running at about three times their pre-pandemic average.

Why it matters:

The September quarter GDP numbers show a strong bounce back in US economic activity. That’s consistent with the broad international story we told back in September of fairly large initial spikes in economic activity following the relaxation of lockdown measures.

But the same GDP numbers also show that the level of GDP remains well down on its pre-pandemic position – about 3.5 per cent below the level of real GDP in the final quarter of 2019.

It's a similar story with the labour market. While there has been a recovery in employment in recent months, that still leaves the overall labour market in much worse shape than pre-pandemic. So, while the US economy lost around 22.2 million jobs lost in March and April this year, by September it had added ‘only’ 11.4 million jobs, leaving a gap of around 10.7 million jobs.

What happened:

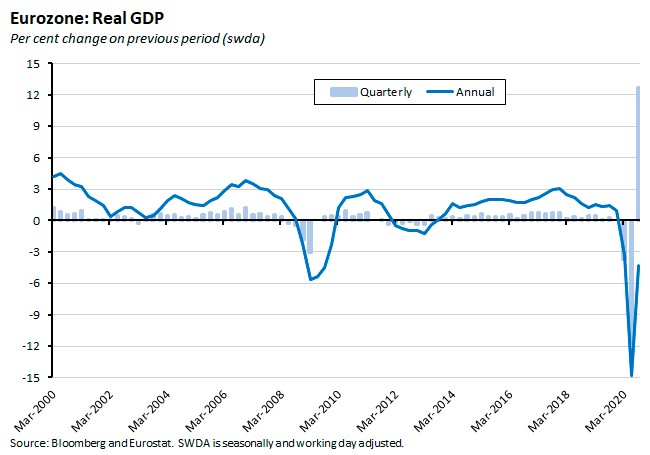

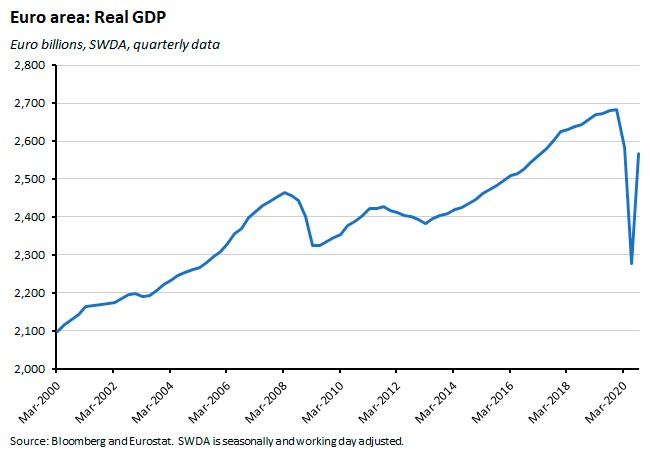

Eurostat’s preliminary flash estimate showed (pdf) eurozone GDP rose 12.7 per cent over the September quarter, following an 11.8 per cent decline in Q2. EU GDP was up 12.1 per cent over the quarter, following an 11.4 per cent decline in the previous quarter.

In annual terms, eurozone output was down 4.3 per cent relative to Q3:2019, while EU output was down 3.9 per cent over the same period.

By country, France (up 18.2 per cent) recorded the highest quarterly increase, followed by Spain (up 16.7 per cent) and Italy (up 16.1 per cent). Germany, which had suffered a shallower downturn in Q2 relative to many of its major European peers, experienced relatively more modest quarterly growth of 8.2 per cent. However, all the countries that published data also reported that their GDP contracted over the year from Q3:2019.

Why it matters:

The eurozone data paints a similar picture to the US numbers reviewed above: the Q3 quarterly growth rate was the fastest since eurozone records began back in 1995 as activity bounced back from its lockdown-induced slump, but that big recovery in activity still left GDP 4.3 per cent below its pre-crisis (Q4:2019) level.

What I’ve been reading . . .

Deloitte Access Economics have published a new report on how the economics of climate change applies to Australia.

The ABS released provisional estimates on regional internal migration, showing that 85,500 people moved interstate in the three months to the end of June 2020. That was 14,800 (15 per cent) less people moving compared with the June 2019 quarter. Queensland gained the most people from net interstate migration (+6,800) over the June 2020 quarter, while New South Wales lost the most (down 4,000). Capital cities had a net loss of 10,500 people from internal migration, the largest quarterly net loss since the series began in 2001, with Melbourne losing the most people, followed by Sydney.

Geoff Raby has a long extract in the AFR from his new book looking at the Australia-China relationship.

For those who’d like a deep dive into the current thinking of some of Australia’s leading econocrats, the transcripts for the economic sessions of last month’s Senate estimates are becoming available, with testimony from 26 October which includes Treasury Secretary Dr Stephen Kennedy and 27 October which includes RBA’s Deputy Governor Dr Guy Debelle.

Warwick McKibbin argues that the RBA’s latest monetary easing needs to be augmented by reform in general and by creating a ‘world-leading framework for climate and energy policy in Australia.’ ANZ Bluenotes on the role of infrastructure after the pandemic.

Bloomberg’s Daniel Moss thinks that this week’s RBA move is a signal to the rest of the world that the climb back from COVID-19 will be ‘long and arduous’.

The RBA’s November chart pack is now available.

This VoxEU column uses Australian data from the past four decades to suggest that past economic downturns have had little impact on mortality except to reduce vehicle transport deaths (but note that while this might tell us something useful about the impact of the current economic downturn on mortality rates, it won’t capture the specific impact of lockdowns).

Buiter and Seibert on punishing corporations vs punishing criminal employees.

The Economist’s Free Exchange column has some cautionary thoughts on interpreting the various Q3 GDP numbers.

Martin Wolf (in both the AFR and the FT) sets out 10 ways that COVID-19 will shape the world in the long term.

Also from the FT, Gavyn Davies on the future of fiscal policy.

GMO’s Jeremy Grantham makes the case for a New Marshall Plan to tackle climate change.

A new Peterson Institute microsite pulls together a collection of work on rebuilding the global economy.

The Talking Politics podcast has an interesting discussion with Daniel Yergin about the world’s new energy map while the Jolly Swagman podcast interviews Tyler Cowen.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content