The Treasurer will hand down the federal budget next Tuesday, 14 May. You can find my Budget 2024-25 Preview here.

Meanwhile, the other key economic focus this week was the RBA Board meeting. Financial markets and economists had expected Australia’s central bank to remain on hold for a fourth consecutive meeting, although there had been media speculation about the possibility of a surprise rate hike in response to the hotter-than-expected Q1:2024 inflation result. In the event, the consensus got it right, and the RBA Board left the cash rate target unchanged at 4.35 per cent.

In considering the accompanying Board statement, readers of last week’s note would have noted a familiar juxtaposition of that disappointingly high March quarter 2024 CPI reading with the ongoing weakness in household consumption. In other words, the RBA continues to see two-sided risks to the economy and still reckons that those risks – that inflation takes longer to return to target than anticipated or that demand proves to be weaker than expected – are broadly balanced. Given that framing, the Board remains cognisant not only of its mandate to return inflation to target, but also of its full employment objective.

The RBA thinks that the current stance of monetary policy is already restrictive, and that keeping the cash rate at current levels will continue to support disinflation. At the same time, the expectation is that this disinflationary process is likely to be bumpy. And a high level of uncertainty regarding both the domestic and international economic outlooks means that the Board judges that the ‘path of interest rates that will best ensure that inflation returns to target in a reasonable timeframe remains uncertain and the Board is not ruling anything in or out.’ That declared agnosticism on whether the next move in the cash rate target is likely to be up or down is largely unchanged from the message delivered in the previous 19 March 2024 Board statement.

So, the RBA is alert to the risks posed by the persistence of inflationary pressures in the economy, but not alarmed enough by them to deliver a rate hike.

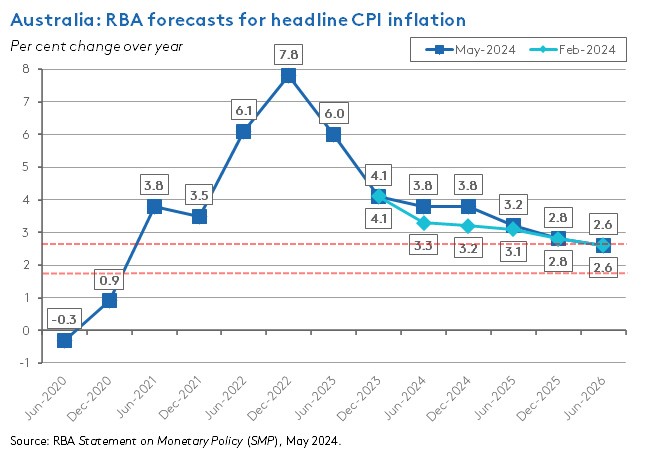

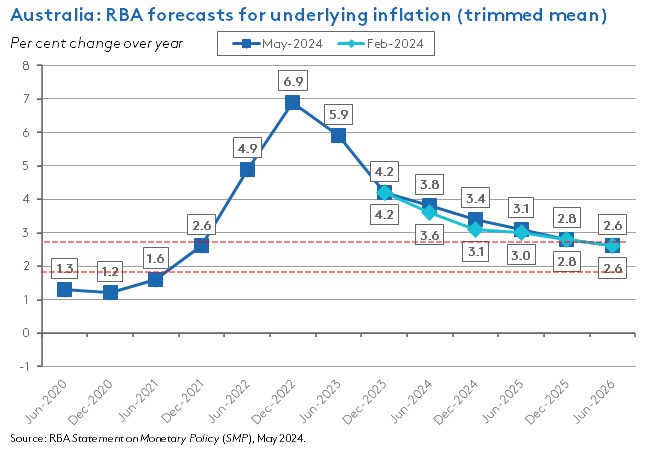

That is not to say that the March quarter inflation result has had no impact on the RBA’s thinking. In both the Board statement and the accompanying May 2024 Statement on Monetary Policy, the central bank acknowledged that inflation is falling more gradually than it had anticipated, with domestic cost pressures remaining stronger and labour market conditions having eased by less than it had expected. In response, the Board did discuss the case for a rate hike this week. Moreover, the central bank has now adjusted its near-term forecasts for inflation upwards, albeit while leaving the timing for a return to target (inflation back to top of the target band by H2:2025 and close to middle of the band in 2026) unchanged.

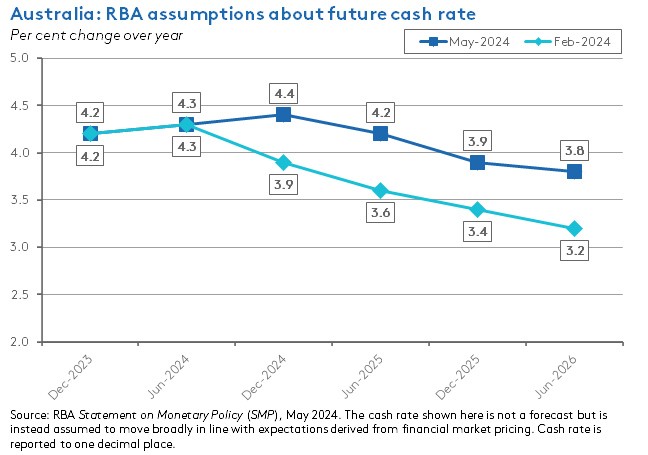

A significant point here is that these new forecasts are conditional on current market assumptions about the future path for the cash rate. Those market expectations see no change in the policy rate until mid-2025 and from next year onwards assume a cash rate trajectory that is 50bp higher than in the RBA’s February 2024 forecasts. That is, based on a higher cash rate than previously assumed, inflation is now projected to be hotter in the near-term and unchanged by the end of the forecast period. All else equal, those adjustments make it harder to see the RBA cutting rates this year. In the aftermath of the March quarter inflation reading, I had pushed my expectations for a first rate cut from the RBA back to ‘November at the earliest’. This week’s messaging from Martin Place suggests that this forecast may well have to be revised backwards again. That said, it does remain important to stay mindful of the downside risks to economic activity from here and not just the upside risks to inflation.

As usual for Budget week, there will be no regular weekly note next week, but there will be plenty of economic content, first on the night of the budget and then in next week’s webinar.

More detailed analysis follows below.

RBA leaves cash rate target unchanged

At its meeting on Tuesday 7 May 2024 the RBA Board decided to leave the cash rate target unchanged at 4.35 per cent. As noted above, the decision to stay on hold was in line both with economists’ forecasts and with financial market expectations, although there had been media discussion in the run-up to this week’s meeting speculating that the March quarter 2024’s disappointingly high inflation reading could prompt a precautionary rate hike along the lines of the one that Australia’s central bank had delivered in November last year.

The accompanying statement from the RBA Board did note that inflation remains high and was falling more gradually than the RBA had expected, which it said was due in large part to persistently strong services inflation. Martin Place continues to detect excess demand in the economy, along with strong labour and non-labour cost pressures. Likewise, it thinks that labour market conditions remain tighter than is consistent with returning inflation to target, and that growth in unit labour costs also remains very high, albeit with some recent signs of a slight moderation.

At the same time, however, the statement also acknowledged that output growth had been subdued, reflecting weak private consumption growth as high inflation and elevated interest rates have squeezed real disposable income, prompting households to cut back on discretionary spending and (in some cases) boost savings.

Along with uncertainties over the persistence of services inflation and the scope for a recovery in consumer spending, the Board statement identified additional uncertainties relating to monetary policy lags, firms’ pricing decisions, future wage growth and the international geopolitical outlook.

Summing up, the Board Statement said:

‘…while inflation is easing, it is doing so more slowly than previously expected and it remains high. The Board expects that it will be some time yet before inflation is sustainably in the target range and will remain vigilant to upside risks. The path of interest rates that will best ensure that inflation returns to target in a reasonable timeframe remains uncertain and the Board is not ruling anything in or out.‘

Comparing that final paragraph to the concluding paragraph in the 19 March 2024 Board Statement reveals two (closely related) changes: An explicit recognition that the decline in inflation is happening more slowly than previously expected and the message that the Board will remain vigilant to upside risks. But the key guidance on the likely future direction of interest rates – that the required path for the cash rate remains uncertain and that the Board feels unable to rule anything in or out – is unchanged from the previous meeting. That is, there was no pivot to indicating that a rate hike was now more likely than a rate cut.

The slowdown in the pace of disinflation was reflected in some upward adjustments to the RBA’s forecast for inflation in the near term (next section). It was also visible in Governor Bullock’s acknowledgment in response to a question in Tuesday’s media conference that the Board had discussed the possibility of a rate hike this month. But in the end, the decision to remain on hold won out.

RBA now expects inflation to be higher for longer

The RBA’s May 2024 Statement on Monetary Policy (SMP) reveals how Martin Place has adjusted its expectations for the economy in light of the data flow since the publication of its early February 2024 assessment. Since then, key data releases have included the March quarter 2024 CPI, the three March quarter 2024 Labour Force releases, the December quarter 2023 WPI, the monthly CPI Indicator for April 2024, the December quarter 2023 National Accounts, and the three March quarter retail trade releases, along with data on vacancies, job ads, house prices and more.

Arguably the biggest news over that period was the surprisingly strong March quarter inflation reading, which came in above both market expectations and the previous (implicit) RBA forecasts. In response, the new SMP forecasts now show inflation running higher for longer for the rest of this year (that is, they predict a slower disinflation process over coming months) before inflation returns to the same trajectory as set out in the previous SMP.

Headline inflation is now expected to be higher by around half a percentage point through until the end of this year, and then slightly higher in the first half of 2025, before returning to within the RBA’s target band by H2:2025 and back to the middle of the band by H1:2026. The RBA points to two temporary factors in the form of higher petrol prices and the legislated end of energy rebates as driving much of this near-term persistence in inflation: Each are anticipated to add about 0.25 percentage points to the headline inflation rate in the final quarter of this year. Then weaker economic conditions are projected to dampen price pressures later in the forecast period.

The picture is similar for underlying inflation as measured by the trimmed mean, although the upward adjustment here is a little more modest. The new forecasts again show a slower disinflation process through this year and into the beginning of next which then converges back on to the previous path.

While the inflation outlook has been revised up, the prospects for activity have been scaled back somewhat. Year-end real GDP growth is now expected to be lower in the June (1.2 per cent vs February’s 1.3 per cent forecast) and December quarters (1.6 per cent vs 1.8 per cent previously) of this year, but then again return to the same growth path set out in February. That reflects weaker household spending (and higher household saving) than predicted earlier this year, as well as a downgrade for dwelling investment.

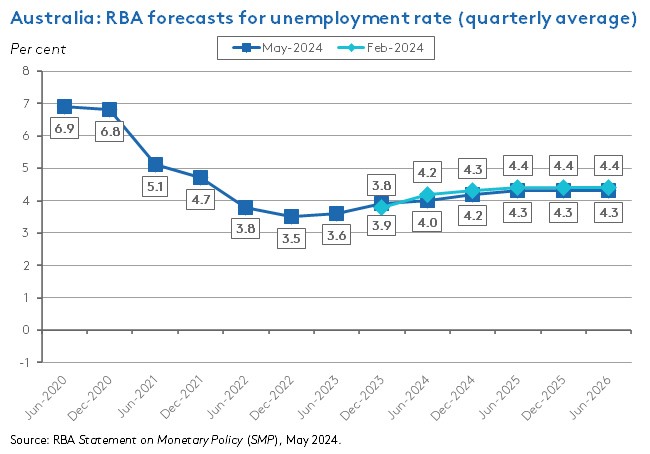

In the case of the labour market, the new forecasts show conditions remaining tighter for longer, with the quarterly unemployment rate projected to be lower than in the February SMP from the June quarter 2024 onwards. The RBA still thinks the economy will return to ‘full employment’ conditions by the end of the forecast period – which going by the forecast numbers it seems to think is consistent with an unemployment rate of around 4.3 per cent.

This slightly tighter labour market is also accompanied by a marginally stronger profile for wage growth, as measured by projected annual growth in the Wage Price Index (WPI). This is now forecast to grow at a rate that is 0.1 percentage points faster through this year than in the February SOMP projections.

Summing up, the second half of this year is now expected to see higher inflation, higher wage growth and lower unemployment than the RBA had anticipated earlier this year. At the same time, real GDP growth is projected to be a little softer.

The other important change is to the technical assumption that the RBA is making about the future path of the cash rate, which underpins the previous projections. Recall that, rather than the central bank plugging in what it thinks the cash rate will be over the forecast horizon, this is instead based on financial market expectations. Back in February, that implied a cash rate target that would remain at its current level of 4.35 per cent until the middle of this year, before falling to 3.25 per cent by mid-2026. As of the May SMP, it implies a cash rate that remains around its current level until mid-2025 before declining to around 3.8 per cent by mid-2026.

That means that, despite the assumption of a materially higher cash rate across the forecast horizon, the expected outlook for inflation is now higher in the near term and unchanged by the end of the forecast period.

Current financial conditions are restrictive, economic conditions subdued, and inflation persistent

The RBA’s judgement in the May SMP is that overall financial conditions are currently restrictive. This is particularly the case for households, where around 335bp of increases in housing lending rates have helped to drive up scheduled interest and principal repayments to an historically high share of household income (although total household debt repayments are still below their 2010-11 peak due to a significant decline in the use of consumer credit). These higher interest rates have contributed to weak consumption growth and increased savings. Financial conditions have also tightened for businesses overall, although the SMP notes that the impact on many medium and larger businesses has been offset by strong financial positions and healthy nominal earnings.

In terms of economic conditions, the SMP notes that growth slowed considerably over the course of last year, driven largely by the squeeze on real household disposable incomes feeding through into softer consumer spending, as well as by a fall in dwelling investment. These sources of weakness have been partially offset by private business and public investment, and by spending from international tourists and students. Overall, and despite last year’s per capita recession, the RBA reckons the level of demand continues to exceed supply. That imbalance is particularly evident in the housing sector, where lower average household size, plus strong population growth, mean strong demand has outpaced limited growth in supply.

Turning to the labour market, the SMP judges that despite some easing in labour market conditions (mainly in the form of falls in hours worked, a rising share of part-time employment and fewer job vacancies) the unemployment rate ‘remains below estimates of the rate consistent with full employment.’ Wage growth is assessed to be around its peak and is expected to decline slightly over the course of this year. The annual rate of growth in unit labour costs is also thought to have peaked, albeit at still elevated levels. The SMP notes that labour productivity growth increased by less than the RBA expected in the December quarter of last year and forecast productivity growth for H1:2024 has been revised downwards accordingly. Labour productivity is then expected to return to around its long-run average after that, although the SMP concedes that this is highly uncertain.

The consequences of a still-tight labour market, demand running ahead of supply and high domestic cost growth have all manifested in the slowdown in the pace of disinflation. The SMP emphasises market services inflation, which it says remains high and broadly based due to ongoing pressure from labour and non-labour (insurance, legal, accounting, and other administrative services) costs. Rental inflation is also high and expected to remain so.

Two key risks to the outlook

The RBA’s new baseline forecast assumes that the gap between demand and supply (or alternatively the output gap, which is expressed as the difference between actual and potential output) will continue to close gradually over the next couple of years. As noted above, that means that although headline inflation will rise in the near term due to temporary factors and underlying inflation will continue to reflect capacity pressures in the economy, disinflation will proceed and inflation will return to target by the end of the forecast period. However, the SMP also highlights two key risks to this outlook.

Risk number one is that if inflation takes longer to return to target than the RBA expects, this will threaten to drive up inflation expectations. The SMP says this would require ‘more monetary policy tightening and a sustained and costly period of higher unemployment to reset inflation expectations and bring inflation back to target.’ This risk could eventuate if there proves to be less spare capacity in the economy than the RBA currently judges to be the case, if demand turns out to be stronger than expected, if services inflation proves to be more persistent than anticipated, if new supply shocks lift headline inflation, or if productivity growth fails to recover.

Risk number two is that if demand proves to be weaker than forecast (or if supply is larger than expected) this could result in spare capacity in the labour market. This downside scenario could emerge from either domestic or international developments. For example, the SMP flags the possibility that recent weakness in household consumption could last longer than expected, that ongoing downside risks to Chinese economic growth are realised, or that there is a further rise in trade tensions.

What else happened on the Australian data front this week?

Updated numbers on retail trade showed the volume of turnover fell 0.4 per cent (seasonally adjusted) over the March quarter 2024 and declined 1.3 per cent in volume terms. The ABS noted that retail sales volumes have now fallen for five of the past six quarters (the exception was the December quarter 2023, when extensive discounting from Black Friday sales boosted volumes) as consumers have reduced spending on large household items such as furniture and electrical goods. In per capita terms, retail volumes have now seen an unprecedented seven consecutive quarterly declines. In annual terms, total volumes have now fallen for four consecutive quarters and per capita volumes have declined for six.

According to the ABS, as of June 2023 there were 2,589,873 actively trading businesses in Australia. That represented a two per cent (50,149) increase in business numbers. The business entry rate over the year was 16 per cent, while the exit rate was 14 per cent.

The ABS said that for the week ending 13 April 2024, payroll jobs fell 0.6 per cent over the month, while rising 2.3 per cent over the year. The Bureau said that while the fall in jobs to mid-April followed the usual seasonal pattern observed around the Easter holiday period, the payroll numbers continued to show slower growth over 2023-24 overall when compared to 2022-23 and a tighter labour market.

ANZ Indeed Australian Jobs Ads rose 2.8 per cent over the month in April 2024 after having fallen one per cent in monthly terms in March (seasonally adjusted). In trend terms, the series is down 14.3 per cent from its peak in November 2022 but remains more than 36 per cent higher than its pre-pandemic level and is also up 3.9 per cent since hitting a trough in November last year.

The ANZ Roy Morgan Index of Consumer Confidence dropped 0.6 points to an index reading of 80.5 points in the week ending 5 May 2024. The index has now been below 85 for a record 66 consecutive weeks. Performance across the subindices was mixed, with improvements for current and future financial conditions but declines for short-term and medium-term economic confidence, and for time to buy a major household item. Confidence in the 12-month outlook for the economy is now at its lowest level this year while confidence for the next five years is at its second lowest level since last December. ANZ speculated that the weekly drop in confidence may have reflected the discussion around a possible RBA rate increase this week. Meanwhile, weekly inflation expectations fell 0.3 percentage points to five per cent.

The ABS published its December quarter 2023 assessment of Barriers and Incentives to Labour Force Participation in Australia. In Q4:2023 there were 19 million people aged between 18 and 75. Of these, 13.9 million (73 per cent) were either employed or had a job to start or return to; 1.8 million (nine per cent) were retired or permanently unable to work; and 3.3 million (17 per cent) did not have a job. Of that final group, 1.2 million (36 per cent) wanted paid work while 2.1 million (64 per cent) did not want a job. Key reasons for not wanting a job included Studying or returning to studies, caring for children, and long-term health condition or disability. Some of the most important incentives to encourage people in this group into the workforce included ‘finding a job that matches skills and experience’, ‘financial assistance with childcare costs’, ‘working a set number of hours on set days’, ‘access to childcare’ and ‘ability to work part-time hours.’

Last Friday, the ABS said its Monthly Household Spending Indicator rose 2.1 per cent over the year (current price, calendar adjusted basis) in March 2024. In annual terms spending was up for both goods (2.5 per cent) and services (1.8 per cent – the lowest rate of growth for this category since February 2021) and was also higher for non-discretionary items (four per cent). But spending on discretionary items fell 0.1 per cent year-on-year. The annual rate of growth for overall spending has slowed from 3.2 per cent in January and four per cent in February.

Also last Friday, the ABS said new loans commitments for housing in March 2024 rose 3.1 per cent over the month (seasonally adjusted) and jumped by 17.9 per cent over the year, reaching more than $27.6 billion. New loan commitments for owner-occupiers rose 2.8 per cent month-on-month and 11.4 per cent over the year to almost $17.5 billion, while new commitments for investors were up 3.8 per cent in monthly terms and 31.1 per cent in annual terms, at a little below $10.2 billion. According to the Bureau, the rise in the value of new home loans over the past year has been driven by increases in average loan size, in line with rising house prices. The number of loans is in line with last year’s outcome. The ABS also noted that the strong growth in lending to investors aligned with historically low vacancy rates and marked increases in rental prices.

Other things to note . . .

- The latest RBA Chart Pack. The May 2024 Statement on Monetary Policy includes a special ‘in depth’ section on Potential Output.

- Peter Martin contemplates what higher for longer rates mean for the budget. The AFR provides a helpful roundup of what we know about the budget so far.

- Also from the AFR, Luke Hartigan and Stella Huangfu push back against recent arguments suggesting a greater role for fiscal policy and supply side measures to argue that interest rates are still the most effective tool for managing inflation.

- Elizabeth Morton and Lisa Greig consider different fiscal options to address current cost-of-living pressures with a focus on temporary vs permanent solutions.

- Grattan with more advice on boosting home ownership: Help the states get rid of stamp duty by providing revenue support; curb negative gearing and halve the capital gains tax discount; and follow through on the current government’s promise to pay the states if they get more housing built.

- In the Lowy Interpreter, Greg Earl considers the supposed choice between ‘nostalgists’ and ‘strategists’ posed by the Australian government’s new industrial policy.

- The PBO’s Small Model of Australian Representative Taxpayers (SMART) can be used to estimate the budgetary impact of changes to personal income tax settings, as well as distributional implications.

- The May 2024 edition of the OECD’s Economic Outlook. Also from the OECD, the Economic outlook for Southeast Asia, China, and India 2024.

- The IMF’s Gita Gopinath gave a speech on Geopolitics and its impact on global trade and the dollar.

- Apollo’s Torsten Lok and Rajvi Shah have a chart pack on Why is the Japanese Yen depreciating? (pdf, via FT Alphaville).

- An Economist magazine briefing on the US fiscal outlook.

- The WTO’s latest Global Trade Outlook and Statistics.

- The McKinsey Global Institute has a new report on small businesses and productivity.

- How and why WFH rates differ across 34 countries. Individualism has the strongest association with WFH, followed by lockdown stringency and population density.

- On the commodification of the iPhone.

- From the WSJ, a reality check for the world’s biggest construction project. Also from the WSJ, the science behind why the world is getting wetter.

- Does AI explain the Great Filter?

- A new Bloomberg podcast series, Voternomics, looks at the interactions between economics, geopolitics and business. Episode one talks to Niall Ferguson about the upcoming US presidential election and episode two talks to Karen Ward about the links between central bank policies and voter dissatisfaction.

- The These Times podcast analyses the global power of the US dollar.

- Two from the FT’s Unhedged Podcast. The first is related to the previous link and discusses why the US dollar is the world’s problem. The second talks to Tim Harford about a fraudster’s guide to magic money. Referenced in the latter is this Harford podcast with the same title on pyramid and Ponzi schemes.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content