Happy 2022 and welcome to the first Weekly of this year and a slightly new format. The main economic story this week was the first RBA board meeting of 2022. The central bank had previously promised to make a decision on the future of its bond purchase program this month, and on 1 February it announced that the program would cease, with the final purchase to take place on 10 February.

At that point, the RBA will have bought more than $350 billion of government bonds and the central bank’s balance sheet will have more than tripled in size to around $650 billion. The RBA also confirmed that it would leave the target for the cash rate unchanged at 10bp, emphasising that the end of the bond purchase program ‘does not imply a near-term increase in interest rates.’

Quantitative Easing (QE) is now set to join Yield Curve Control and the Term Funding Facility as another unconventional monetary policy tool that Martin Place deems no longer necessary to support the Australian economy as it emerges from the COVID crisis. The ultra-low cash rate will, however, remain in place.

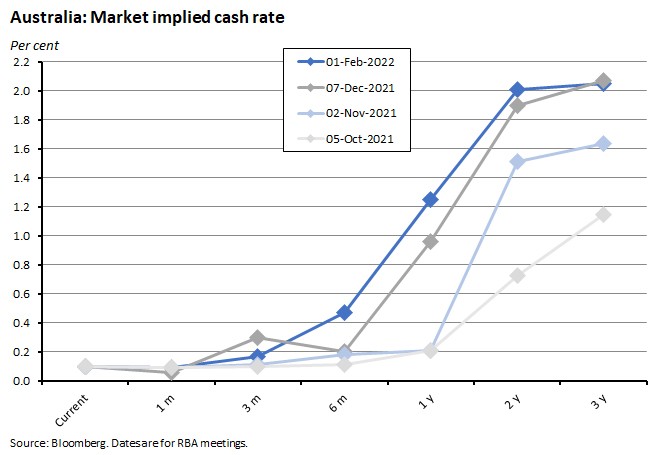

Many market participants had been expecting an exit from QE this month and that expectation has been met. But the reading on their other expectation for the February meeting – that of a potential shift in RBA rhetoric towards something rather more hawkish than was the norm through 2021 – is more mixed. On the one hand, this week has seen the RBA travel some considerable distance from its position last year, with RBA Governor Lowe conceding that a rate hike in 2022 is now a ‘plausible scenario.’ On the other hand, Lowe added that it was also plausible that ‘the first increase in rates is still a year or more away,’ and stressed ongoing uncertainties around the inflation outlook. He also said that he continues to find market pricing on interest rates ‘surprising’. So, although the RBA has moved closer to the market’s view, the gap between the two still appears quite substantial.

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify

The RBA vs the market

That means that one of the key macro themes from last year – the significant divergence between financial market pricing and central bank views on the likely path for interest rates – persists. In 2021, markets were pricing in a considerably more forceful monetary policy normalisation than the much more cautious trajectory set out in a series of RBA speeches. Back in November last year (when the RBA exited from its yield curve control policy), for example, the Governor had described market pricing on interest rates as a ‘complete overreaction’ to inflation data and argued that ‘the latest data and forecasts do not warrant an increase in the cash rate in 2022.’ By the time of the 7 December 2021 meeting, the tone had changed somewhat – there was no longer any mention of a date as the RBA stepped back from any kind of calendar-based forward guidance – but taken overall the final statement of 2021 remained pretty dovish.

There had subsequently been some speculation that developments since the 7 December 2021 RBA meeting would have convinced the central bank that not only could it safely exit QE this month but also that it would need to be considerably more aggressive in its approach towards returning the cash rate to a less stimulative setting. Two pieces of data in particular seemed to point in that direction.

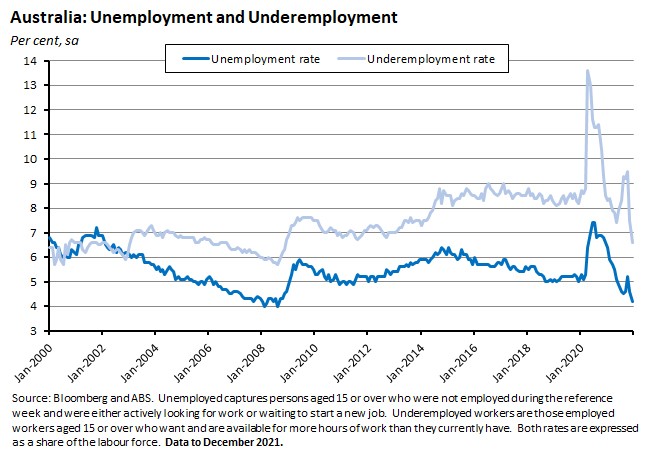

First, last month saw the release of the December labour market report from the ABS. This showed employment increasing by almost 65,000 people (following on from a huge 366,000 jump in November), the unemployment rate falling by half a percentage point to just 4.2 per cent, and the underemployment rate dropping by 0.8 percentage points to 6.6 per cent. Australia’s unemployment rate is now at its lowest since August 2008 and the underemployment rate at its lowest since November 2008. The RBA had been clear that it wanted to see further progress on the labour market before moving on rates, and the December labour market report certainly delivered some significant progress.

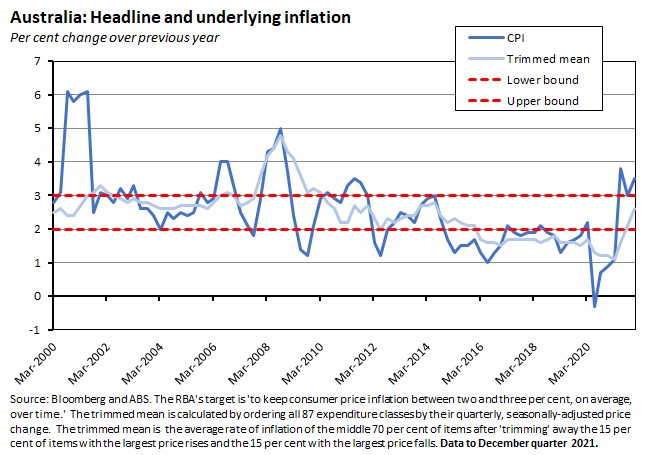

Five days later, the December quarter 2021 inflation numbers reported that the headline CPI had risen by 1.3 per cent over the quarter and 3.5 per cent in annual terms, exceeding economists’ median forecasts of one per cent and 3.2 per cent increases, respectively. At the same time, the RBA’s preferred measure of underlying inflation – the trimmed mean – rose one per cent over the quarter and 2.6 per cent over the year. Again, that was a stronger result than expected by the consensus view, which had predicted a 0.7 per cent quarterly rate and a 2.3 per cent annual print. Moreover, both results were also above the RBA’s forecast in the November 2021 Statement on Monetary Policy, which had projected annual rates of headline inflation at 3.25 per cent and underlying inflation at 2.25 per cent.

The Q4:2021 result means that headline inflation has now been at or above the top of the RBA’s two to three per cent target range for three successive quarters while underlying inflation has been within the target band for the past two quarters.

Both ABS releases, then, were consistent with an economy that had ended last year on a fairly strong note, with a tightening labour market and rising inflation readings. Since then, of course, the short-term outlook has been clouded by the impact of the Omicron outbreak. But here the current market consensus is that the variant will only be a temporary disruption and will not significantly dent either growth or inflation prospects for the year as a whole.

To some extent, the RBA appears to be on board with all this. Importantly, it has upgraded its own economic forecasts. In a speech this Wednesday on the year ahead, Governor Lowe provided an overview of the updated economic forecasts that will be released on Friday in the February 2022 Statement on Monetary Policy. After noting that the economy last year significantly outperformed the RBA’s projections in terms of economic growth, the unemployment rate and (to a lesser extent) wage growth, Lowe said that the RBA now reckons that real GDP will grow by around 4.25 per cent this year and by two per cent next year, and that the unemployment rate will fall below four per cent later this year and be around 3.75 per cent by year-end, and then be sustained at around this rate through 2023.

The RBA is also expecting a higher rate of inflation than it was forecasting last year. After noting that headline inflation has been pushed up by a combination of higher petrol prices, higher prices for newly built homes and disruptions to global supply chains, Lowe said that the RBA’s central forecast for underlying inflation is for it to rise from December’s 2.6 per cent rate to peak at around 3.25 per cent later this year before slowing to around 2.75 per cent and then staying around that rate through 2023; underlying inflation is now forecast to be in the target range through this year and next.

Similarly, on Omicron, the RBA view is that although the outbreak has affected the economy, the impact has not been large enough to derail the recovery.

Together with the actions of other central banks (most of the RBA’s peers have either already completed their own QE programs or are about to do so) and along with concerns over the functioning of the bond market (where the RBA already owns some 42 per cent of Australian government securities on issue), the new data and forecasts were enough to convince Martin Place that there was no longer any need to persist with its bond purchase program.

Mixed messages on the cash rate

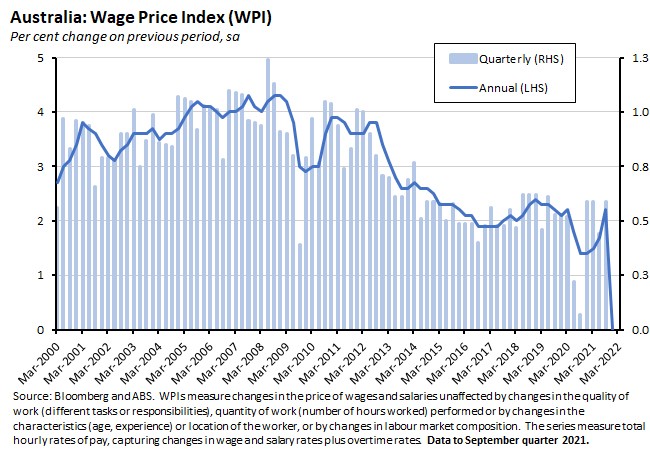

The picture on the cash rate is more nuanced, however. In terms of the outlook for monetary policy, the 1 February Statement said that the RBA Board will not increase the cash rate until actual inflation is sustainably within the two to three per cent target range, adding that although inflation has picked up, in the RBA’s view ‘it is too early to conclude that it is sustainably within the target band.’ The Statement also noted that wage growth remained modest and that the central bank still thinks ‘it is likely to be some time yet before aggregate wages growth is at a rate consistent with inflation being sustainably at target.’

Governor Lowe elaborated on these themes in his speech the following day. He said that in the near-term, the RBA reckons that ongoing difficulties on the supply side – some of them arising from the new Omicron variant – are likely to keep upward pressure on prices. But he argued that these pressures will fade as supply side issues are resolved. At that point, wage growth will have to take over as the driver of inflationary pressures, but here Lowe reminded his audience that wages in Australia can be subject to significant inertia, due to the combined effects of multi-year enterprise agreements, annual award wages and public sector wage policies. Partly as a result, the RBA thinks that wage growth as measured by the Wage Price Index (WPI) will run at 2.75 per cent this year and three per cent over the course of 2023. Previously, the Governor has said that wage growth of ‘three point something’ will be required for inflation to be sustainably within the target band. Moreover, Lowe added, there are significant uncertainties on both the wage and inflation fronts, including how labour costs will evolve in a world where the national unemployment rate could be below four per cent for the first time in decades (although Lowe did note that wage growth remained modest in NSW and Victoria when both states enjoyed unemployment rates of around four per cent some years back).

Lowe was again explicit that ‘the decision to end the bond purchase program does not mean that an increase in the cash rate is imminent’ and reiterated that the precondition for a rate move is that inflation is sustainably within the target range. ‘Sustainably’ is the key qualifier here, given that both headline and underlying inflation are already either within or above that target range. Lowe said the RBA does not have a specific definition of what ‘sustainably in the target range’ means, continuing:

‘it is too early to conclude that inflation is sustainably in the target range. In terms of underlying inflation, we have just reached the midpoint of the target range for the first time in over seven years. And this comes on the back of very significant disruptions in supply chains and distribution networks, which would be expected to be resolved over the months ahead. It also comes at a time when aggregate wages growth in Australia remains low and is at a rate that is unlikely to be consistent with inflation being sustained around the midpoint of the target range…there is a range of significant uncertainties here that will take time to resolve [and Australia is] in the position where we can take some time to obtain greater clarity on these various issues.’

The new monetary policy experiment

Lowe also made the point that in considering the future stance of monetary policy it ‘is also relevant that Australia is within sight of a historic milestone – having the national unemployment rate below four per cent.’ Full employment is one of the RBA’s objectives, and Martin Place now thinks there is the chance to achieve this at a level of unemployment not seen in Australia since the early 1970s. To that end, the RBA is prepared to be patient when it comes to normalising monetary policy – that is, it will keep running the current policy experiment of ultra-low rates for a bit longer to see if that sub-four per cent unemployment rate can be attained and then maintained.

Again, just how long the experiment will be sustained will be determined by how quickly supply-side constraints resolve themselves, how fast consumption patterns return to their pre-COVID norms, and how rapidly wage growth picks up as the labour market continues to tighten.

The RBA view has shifted here: as noted above, Lowe concedes that one plausible scenario is for a cash rate hike this year, although he also said that it was still plausible that the first hike could still be a year or more away. Even so, the RBA continues to think that the market has got it wrong, with Lowe noting that he found it ‘surprising’ that market pricing implied the same increase in interest rates in Australia as the United States by year-end, despite Australian inflation being half that of the US inflation rate and the Australian labour market looking much less hot than its US counterpart.

How did markets respond to this messaging? On 31 January, the day before the RBA meeting, market pricing (based on a Bloomberg model using cash rate futures) implied a more than 80 per cent probability of a cash rate hike by the June 2022 RBA meeting, and a 100 per cent probability of four rate hikes by the December RBA meeting. By the 3rd of February – after the meeting and Lowe’s speech the following day – the profile had changed to an 80 per cent probability of a cash rate hike by the July 2022 RBA meeting and 100 per cent of three rate hikes (and more than 80 per cent probability of a fourth) by the December meeting.

In other words, market pricing was only modestly tempered by the RBA messaging this week and continues to signal that this year will see more rapid central bank action than currently implied by the RBA’s commentary.

What else happened on the Australian data front this week?

House prices

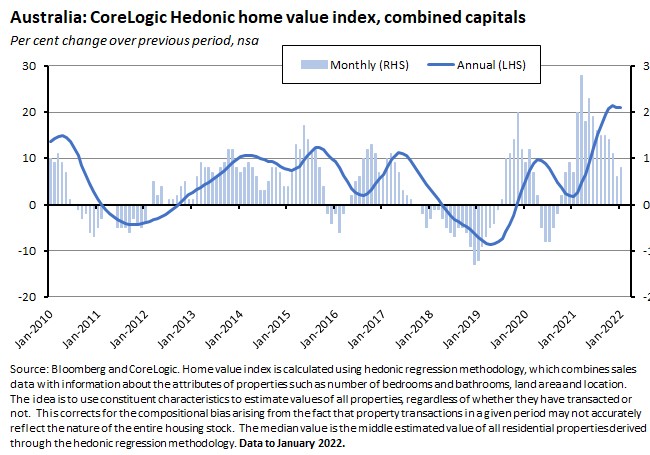

One important consequence of the RBA’s ultra-low interest rate policy has been a soaring housing market. This week, CoreLogic’s national housing values index rose by 1.1 per cent in January 2022 to be up 22.4 per cent over the year. That marks the highest annual rate of growth seen since June 1989 and the typical Australian home is now worth $131,000 more than it was in January 2021. The combined capitals index rose 1.8 per cent over the month and was up 21.3 per cent over the year. Three of Australia’s eight capital cities (Sydney, Melbourne and Canberra) now have median house prices in excess of $1 million, with Sydney at almost $1.39 million. The monthly pace of increase picked up slightly from December’s one per cent growth rate, and five of the eight capital cities also record a modest rise in month growth, although CoreLogic cautioned that the housing stock is typically thinly traded during January. The data provider also noted that while much of last year saw a synchronised and broad-based upswing in home values, recent developments have seen more diversity, with rapid monthly growth continuing in Brisbane and Adelaide while growth is slowing in Sydney and Melbourne.

Housing lending

Sticking with the housing market, the ABS said that new loan commitments for housing rose 4.4 per cent over the month in December 2021 (seasonally adjusted) to be 26.5 per cent higher over the year. At $32.8 billion, total new loan commitments are now at a record high. The average national loan size for owner-occupiers (at $602,000) is likewise at a record high. Lending to owner-occupiers was up 5.3 per cent month-on-month and 12.4 per cent year-on-year while lending to investors rose 2.4 per cent in monthly terms and jumped by almost 74 per cent in annual terms. Lending to investors hit a record $10.3 billion in December and accounted for about one-third of all new commitments in dollar terms. The previous peak for investor lending was in April 2015, at which point lending to investors accounted for some 46 per cent of all loan commitments.

Building approvals

Total dwellings approved rose 8.2 per cent over the month (seasonally adjusted) in December 2021 although they were down 7.5 per cent relative to December 2020. The ABS said approvals for private sector houses fell 1.8 per cent in monthly terms to be down more than 21 per cent in annual terms while approvals for private sector dwellings excluding houses jumped 27.5 per cent month-on-month and 24.5 per cent year-on-year.

Retail turnover

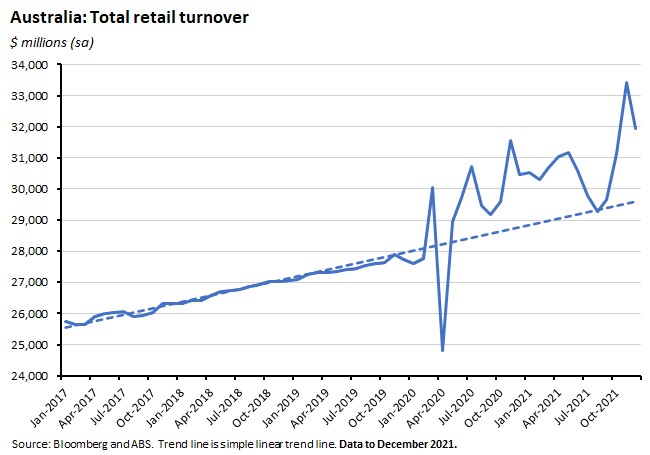

According to the ABS, nominal retail turnover fell 4.4 per cent over the month in December 2021 (seasonally adjusted) but was still 4.8 per cent higher than in December 2020. Five of the six retail industries saw turnover fall last month (food retailing including supermarkets was the only exception) and December’s monthly decline follows substantial gains in November (up 7.3 per cent) and October (up 4.9 per cent) last year. It also marks the steepest monthly drop since April 2020. The Bureau reported that softer trading conditions emerged towards the end of the month as consumers became increasingly concerned about the Omicron variant, but also emphasised that that the level of retail turnover remains elevated relative to pre-pandemic results, with last month’s result the send highest level recorded in the series.

Consumer confidence

ANZ Roy Morgan weekly consumer confidence rose 1.7 per cent last week, reflecting the downward trend in Omicron case numbers across Australia. Four out of the five subindices registered gains, with assessments of current and future economic conditions, future financial conditions and time to buy a major household item all improving, although current financial conditions fell. Weekly inflation expectations fell back to 4.7 per cent.

International trade

The ABS said that the Australia’s goods and services trade balance (seasonally adjusted) recorded a surplus of $8.4 billion in December last year. That was down $1.4 billion from November’s surplus and reflects a one per cent monthly rise in export values and a five per cent increase in import values.

Other things to note . . .

- The RBA’s latest chart pack is now available. It’s a nice, easy way to get a quick, graphical overview of the state of the economy.

- Jeff Borland thinks that the RBA’s ‘historic milestone’ target of hitting an unemployment rate below four per cent is possible.

- While financial markets have long been predicting rate hikes this year, and with many market economists now joining them, a recent survey of economists (conducted before this week’s RBA meeting) suggests that there are still plenty of forecasters sticking with the call of no change until 2023.

- These have both been out a little while now, but the IMF’s January 2022 World Economic Outlook Update and the World Bank’s latest Global Economic Prospects offer useful overviews of key trends and risks in the global economy.

- Also from the IMF, the latest China Article IV staff report. It provides a useful review of the macro, regulatory and other policies that have contributed to slowing growth along with an assessment of the challenges to financial stability.

- Jason Furman asks, why did almost every forecaster fail to predict soaring US inflation last year?

- Related, NYMag profiles Larry Summers, arguably the leading critic of the Biden presidency’s economic approach.

- An FT Big Read on China’s zero-COVID policy – tightly sealed borders, citywide lockdowns, mass testing and tech-based contact tracing are being deployed to offset the vulnerabilities created by China’s fragile healthcare system and the fading efficacy of its vaccination program. See also this WSJ piece on China’s Southern Great Wall.

- The Economist magazine has a briefing on the Ukraine crisis.

- A VoxEU column on the role played by trust in managing the health and economic consequences of COVID.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content