COP26 concluded with the signing of the Glasgow Climate Pact. Judged against the key benchmarks of delivering enough emissions reductions to keep the world on track to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement and stumping up the promised financial support for poor and developing countries to fund climate mitigation and adaptation, Glasgow was a clear disappointment. But there were enough achievements to keep the show on the road to Egypt and COP27 next year.

On the Australian economic data front, this week was all about wage growth. The release of the minutes from the 2 November Monetary Policy Meeting (the one which saw the RBA dump its yield target) and a speech from RBA Governor Lowe on recent trends in inflation both reiterated the RBA’s view that there is little near-term risk of an inflationary breakout and that consequently financial markets are wrong in their assessment that the cash rate will start to rise next year. The Australian labour market sits at the heart of the RBA’s analysis, with Martin Place arguing that (1) it will only hike the cash rate once inflation is sustainably in the two-three per cent target band; (2) meeting this condition likely requires wage growth of ‘three point something’; and (3) due to a combination of the nature of Australia’s labour market institutions, the focus of Australian businesses on keeping down costs, and the likely return to high participation rates post-lockdown, the acceleration of wage growth to this level is likely to be a relatively gradual process.

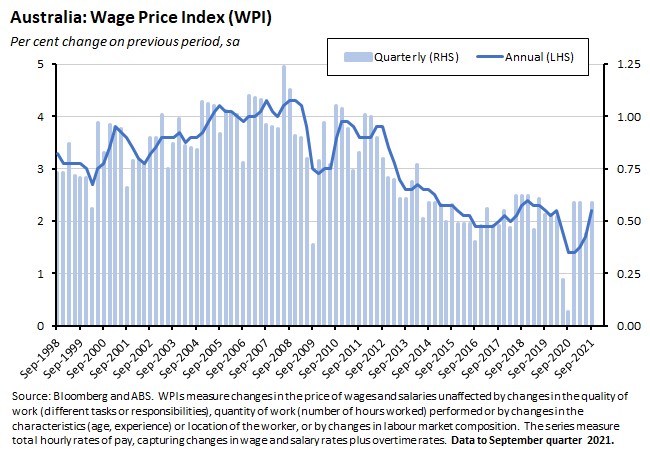

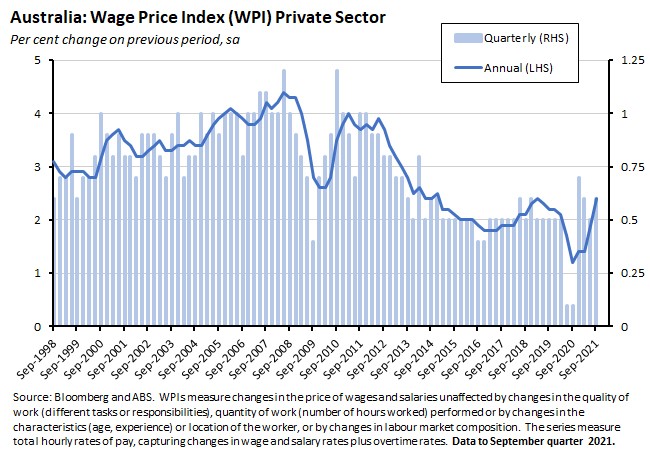

Given that context, the September quarter Wage Price Index (WPI) release was an important data point. And it turned out to be one that was more consistent with the RBA’s view of the world than with those expecting a wage and inflation breakout. The headline WPI rose 0.6 per cent over the quarter and 2.2 per cent over the year. That does represent an ongoing recovery from last year’s pandemic-induced slump. But both growth rates are comfortably below the series’ average. There’s a deep dive into the Q3 WPI numbers below and we also talk about the gap between popular narratives of rising wage pressures and the Great Resignation vs the reality of actual wage and labour market mobility data in this week’s Dismal Science podcast. Listen and subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify

This week’s linkage includes how the Future Fund thinks about the post-COVID world order, speeches from the RBA on innovation and the future of payments, confessions of a former RBA Board Member, how NFTs create value, Martin Wolf’s choice of best economics books from the second half of this year, and the rise and rise of the global balance sheet.

What I’ve been following in Australia . . .

What happened:

The ABS said that in the September quarter of this year, Australia’s Wage Price Index (WPI) rose 0.6 per cent over the quarter (seasonally adjusted) to be 2.2 per cent higher over the year.

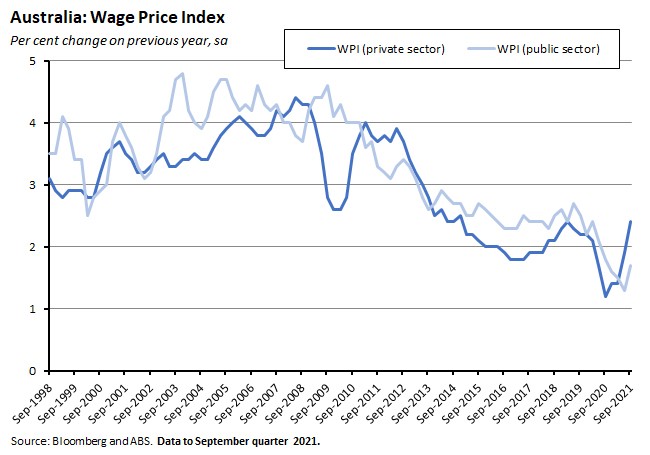

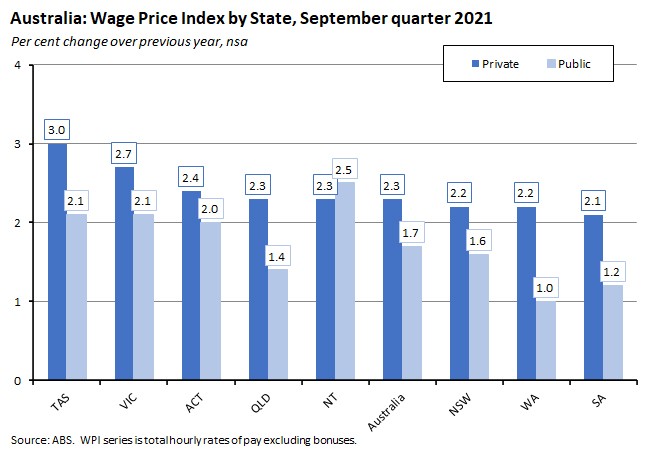

The WPI for the private sector rose 0.6 per cent over the quarter and 2.4 per cent over the year while the WPI for the public sector rose 0.5 per cent quarter-on-quarter and was up just 1.7 per cent year-on-year.

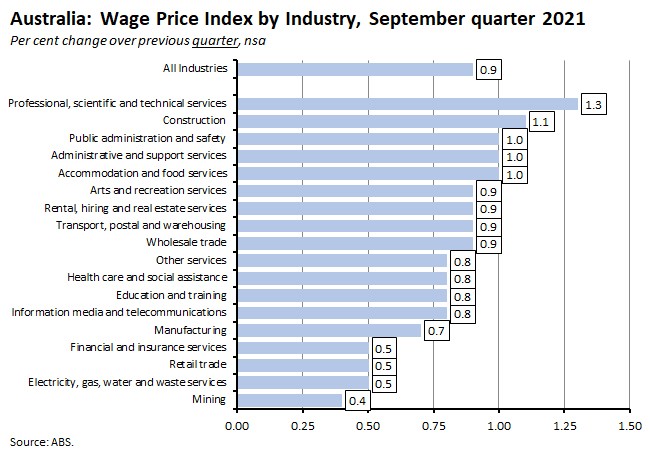

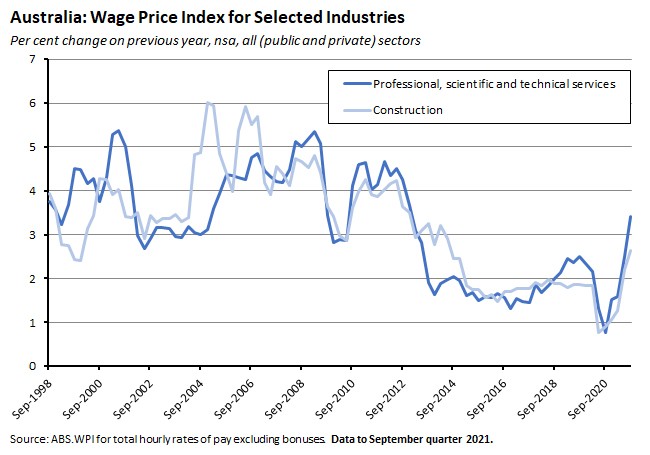

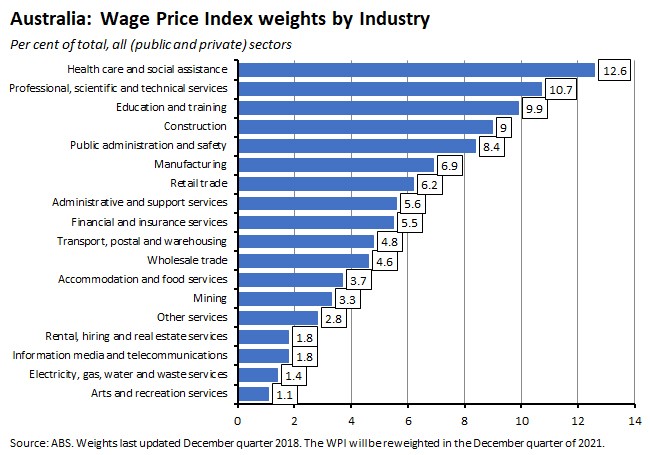

By industry, wage growth over the quarter was strongest in professional, scientific and technical services at 1.3 per cent, followed by construction (up 1.1 per cent), public administration and safety, administrative and support services and accommodation and food services (all three up one per cent).

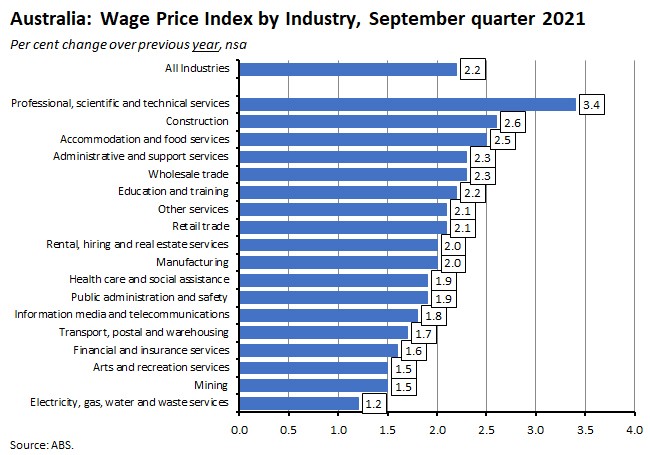

In annual terms, wage growth was again strongest in professional, scientific and technical services (up 3.4 per cent), followed by construction (up 2.6 per cent), accommodation and food services (up 2.5 per cent) and administrative and support services and wholesale trade (both up 2.3 per cent).

By state, quarterly growth was fastest in Tasmania and the ACT. In annual terms, growth was fastest in Tasmania (up 2.7 per cent over the year) and softest in South Australia (up 1.8 per cent).

According to the ABS, contributions to the WPI by the method of setting pay have now returned to their regular quarterly pattern, with jobs covered by individual arrangements driving a larger share of wage growth (the Bureau pointed out that wages and salaries for these jobs tend to react more quickly to labour market conditions than jobs covered by enterprise agreements and rewards). The contribution from Enterprise Agreements increased in the September quarter following the end of public sector wage freezes that were a feature of the pandemic period and the contribution of Award increases reflected the decision by the Fair Work Commission Annual Wage Review to stagger the implementation of awards over time for a second consecutive year, with the majority of Award-based rises spread over the September and December quarters of this year.

The ABS also included additional analysis of the frequency of wage increases. The Bureau noted that prior to the pandemic, the frequency of wage rises had followed a fairly regular pattern over the past decade, with the WPI typically seeing 35 to 40 per cent of jobs record a wage rise in the September quarter. But in the September quarter of last year, the share of jobs with a wage rise fell to just 20 per cent as wage negotiations were postponed and many organisations implemented wage freezes in response to COVID-19. Now, according to the ABS, by the September quarter of this year, the share of jobs recording a wage increase had returned to the previous range. By pay setting method:

- Some 25 per cent of jobs covered by individual arrangements recorded a pay rise in the September quarter. A large share of this group also saw a shift away from their regular pre-pandemic pattern of annual wage increases. Typically, around 55-60 per cent of September wage increases have been annual rises but this year, only 22 per cent were annual. Instead, there were increase both in the share of wage rises occurring after an extended period (more than one year), largely due to wage freezes, as well as increases in the share of jobs recording a second rise within the year. Some of the latter was due to the impact of award-reliant jobs but the ABS noted that it also reflected ‘specific in-demand occupations that saw wages adjusting to new market rates.’

- After having been affected by pandemic-related wage freezes, Enterprise bargaining agreements returned to what the ABS says was a more regular pattern of wage rises, with 35 per cent of jobs reporting a wage increase.

- With regard to modern awards, the ABS noted that in the last two annual reviews the Fair Work Commission has staggered the timing of Award increases across 2020 and 2021. This meant that there was more than a year between wage rises in 2020 for over half of Award jobs, and therefore less than a year between wage rises for those jobs in 2021. Pre-pandemic, around 80 per cent of Award jobs would normally record wage rises in a typical September quarter but the staggered implementation of the latest Annual Wage Review meant that only 55 per cent of Award jobs recorded an increase in the September quarter of this year, with most others expecting rises in the December quarter 2021.

Why it matters:

The September WPI result is an important data point for the ongoing debate about inflation and interest rates in the Australian economy.

Readers will remember that in the aftermath of the RBA’s decision to exit from its yield curve control policy we spent some time looking at the divergence in expectations around the likely trajectory for inflation and the cash rate between the path implied by financial market pricing and what the RBA was indicating. Financial markets have been pricing in cash rate increases starting next year even though the RBA has been adamant that no policy rate increase is likely until 2023 at the earliest, and quite possibly not until 2024. That is because the RBA is yet to see compelling evidence of sustained inflationary pressures in the economy, and that in turn is in large part because it is yet to detect any sign of significant wage pressures. The central bank also thinks that this state of affairs is likely to persist for some time: according to the November 2021 Statement of Monetary Policy, the RBA forecasts that while wage growth will pick up in line with a recovering labour market, it will do so only gradually, with the annual rate of increase of the WPI forecast to be running at just 2.5 per cent by the end of next year and only rising to three per cent by the December quarter of 2023. And since the central bank also says that a precondition for a rise in the cash rate is for inflation to be sustainably in the RBA’s two-to-three per cent target range, and since the RBA also believes that this sustaining this level of inflation requires wage growth with a three in front of it, the RBA does not expect to move on interest rates any time soon. Governor Lowe again set out this logic in a speech on recent trends in inflation he delivered this week (see below for a detailed discussion).

In this context, September’s results look much closer to the RBA’s view of the world than to the market’s take. That quarterly rise of 0.6 per cent is below the pre-pandemic series average (from Q4:1997 to Q1:2020) of 0.8 per cent. Likewise, the 2.2 per cent year-on-year increase is below the pre-pandemic series (Q3:1998 to Q1:2020) average of 3.2 per cent. And remember, that year-on-year increase was inflated by the subdued state of wages in the September quarter of last year, when wages only rose by an anaemic 0.1 per cent in quarterly terms.

In short, there’s no convincing case to be found in any of these headline numbers that wage growth is surging to the kind of level that would underpin a sustained increase inflation and require an urgent monetary policy response. Score this one for the RBA’s worldview.

So, does that mean that the argument over inflation is done? Not at all. For at least two reasons.

First, and most importantly, this is only one quarter’s wage growth. The debate here is mostly about how future wage growth will unfold over 2022. Yes, it is important that there’s no sign yet of a dramatic wage break out. But the September quarter data relate to a period in which COVID-19 restrictions were in place across New South Wales, Victoria and the Australian Capital Territory. Wage growth is likely to pick up further as the economy re-opens. The questions are, by how much, and how quickly?

Second, and perhaps less compellingly, if you look hard enough it is possible to find some evidence in the Q3 WPI of wage pressures. As a starting point, the overall WPI reflects continued weakness in public sector wage growth (which has an index weight of about 23 per cent). Private sector wage growth was faster in quarterly and annual terms, with the pace of quarterly increase running above the kind of rates seen between 2014 and 2019. Even so, when compared to the history of the series overall, the rate of increase in the private WPI was not particularly dramatic.

There were more impressive increases to be found in certain subsectors of the labour market. The ABS remarked that ‘Pockets of wage pressure continued to build for skilled construction-related, technical and business services roles, leading to larger ad hoc rises as businesses looked to retain experienced staff and attract new staff.’ As noted above, that was reflected in very strong annual and quarterly WPI increases for the professional, scientific and technical services industry overall, as well as markedly faster wage growth in construction.

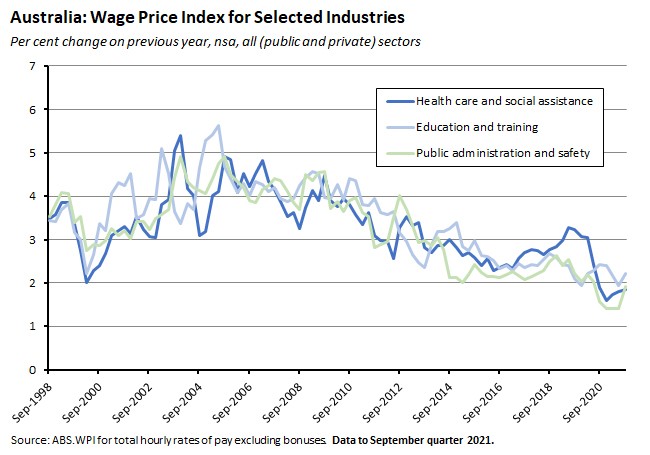

Together, those two industries have a combined weight of about 20 per cent in the WPI. Three other industries (health care and social assistance, education and training, and public administration and safety) have a combined weight of about 31 per cent and collectively these five industries have a weight of about 51 per cent in the WPI.

Wage growth in these other three industries has also picked up. But here the pace of growth remained very moderate in Q3 and was still below two per cent in annual terms for health care and for public administration.

Another piece of evidence of the emergence of some ‘pockets’ of wage pressure can be found in the Bureau’s data on the frequency of wage increases. As noted earlier, the ABS highlighted that of the 25 per cent of jobs covered by individual arrangements that enjoyed a wage increase in September, about 41 per cent recorded a second increase within the space of a year and some of those increases reflected ‘specific in-demand occupations that saw wages adjusting to new market rates.’

What happened:

The RBA published the Minutes of the 2 November Monetary Policy Meeting of the Reserve Bank Board. And later the same day, RBA Governor Philip Lowe gave a speech on recent trends in inflation.

The minutes set out the RBA’s evolving thinking on wage growth and inflation. On wages, they note:

‘Wages growth was expected to pick up as remaining wage freezes and cuts implemented in 2020 were unwound and the labour market tightened. Forecast growth in the Wage Price Index had been revised up a little to around three per cent by the end of 2023…Inertia in wage-setting practices was likely to moderate the increase in wages growth…wages growth was starting from a low base – disaggregated data and information from the Bank's liaison program suggested only a small share of workers were receiving increases in wages of more than three per cent…members acknowledged there was uncertainty around how wages growth would respond to the unemployment rate being near four per cent for an extended period…The effect on overall labour market conditions of the reopening of the international border…was also uncertain.’

On inflation, the minutes discuss why Australia’s inflation profile looks different to the experience of many other advanced economies:

‘…flexibility in labour supply implied there would be less upward pressure on wages in Australia…the effect of global supply disruptions on inflation had been less pronounced in Australia than in other parts of the world, including in energy markets…the starting points for inflation and wages growth were lower in Australia than in many other advanced economies.’

But they also highlight a shift in the central bank’s view on inflation prospects and the greater uncertainty around the RBA’s central scenario:

‘Members agreed that the distribution of possible outcomes for inflation had widened. If price pressures in global goods markets persisted for longer than expected, the extent of the pass-through to domestic prices could be stronger than in the central scenario. Workers might also demand higher wages as compensation for higher inflation outcomes. If employers passed these increased wage costs on to consumers, this would feed into higher inflation outcomes…it was also possible that global goods demand would ease over the coming year or so, around the same time that more goods supply came online. This could see price pressures in global goods markets dissipate and lead to lower inflation outcomes in Australia.’

And while the previous comment suggests both upside and downside risks to the RBAs inflation forecasts, the minutes also confirm that in practice risks are skewed towards higher inflation:

‘Members acknowledged that the risks to the inflation forecast had changed, with the distribution of possible outcomes shifting upwards. The main uncertainties related to the persistence of the current disruptions to global supply chains and to the behaviour of wages at the lowest unemployment rate in decades.’

Governor Lowe’s speech covered similar territory, with a discussion on global inflation developments, Australia’s inflation experience, and the implications for monetary policy.

On global inflation, the governor said the big story was a shift in the balance of demand and supply as a result of the pandemic. Consumers switched demand from services to goods and the resultant ‘surge in demand for goods quickly ran up against a supply side that was not flexible enough’ mainly because just-in-time supply chains do not cope well with sudden, large shifts in demand. This adjustment problem was further compounded by the disruptive impact of the pandemic on supply chains and logistics. A similar story applied to commodity markets, where even pre-pandemic ‘a number of these markets were operating at a point where the short-run supply curve was quite steep. As a result, even modest shifts in demand moved prices significantly.’

Lowe then argued that a critical question for the extent to which these supply-side price pressures translate into longer-term inflationary pressures relates to how the labour market responds:

‘It is unusual to have persistently higher inflation without persistently higher wages growth (unless there is a shift lower in labour productivity growth). The two generally go together. There have been historical exceptions to this, and other factors that affect firms' costs and mark-ups can have persistent effects. But at the current juncture, the labour market is the key.’

In this context, Lowe’s speech highlighted two key factors to watch: (1) how inflation feeds into inflation expectations and then into wage norms and wage demands; and (2) how the balance of supply and demand in the labour market shifts as economies open up and the demand for labour-intensive services increases.

In the case of Australia, Lowe noted that although we too have experienced a lift in inflation, it has been less pronounced than in many other countries. Echoing some of the points made in the minutes, Lowe argued that this was the product of two differences. First, energy prices in Australia have been trending lower, partly as a result of lower electricity prices thanks to increased capacity from wind and solar generators. Second and more importantly, Australia’s labour market looks different:

‘Labour force participation in Australia remains high and the wage-setting processes – including multi-year enterprise agreements and the annual minimum wage case – impart a degree of inertia into aggregate wage outcomes. Wages growth is expected to pick up, but to do so only gradually. Our business liaison suggests that most businesses retain a strong cost control mindset and are seeking to use measures other than raising base wages to attract and retain staff. There are some jobs that are in very high demand where wages have increased, but we are yet to see a broad-based pick-up in wages growth.’

In terms of what all this meant for the outlook for inflation, Lowe argued that on the one hand some normalisation in consumption patterns both globally and in Australia seemed likely to alleviate at least some of the upward pressures on Australian inflation going forward, but that on the other hand, a tightening labour market would lead to gradual increases in wage growth over time.

Why it matters:

There are four key messages to be derived from the RBA minutes and this week’s speech from the RBA governor.

First, the central bank has shifted its view on inflation. It acknowledges that the risks to its inflation forecast have changed, and in particular that the distribution of possible outcomes has shifted upwards.

Second, and despite this shift, the RBA does not think that Australia is experiencing the same kind of inflation surge that is currently underway in some other advanced economies. For several reasons, including the nature of our labour market institutions, the RBA thinks Australia is different.

Third, central to the RBA’s views on inflation are its assessment of the labour market. It’s judgment is that wage growth will accelerate from here, but that due to certain features of the Australian labour market (wage-setting processes that create significant inertia for wage outcomes, a strong cost focus by businesses, the prospects for a quick snap back in participation rates) this acceleration will be a relatively gradual one. More concretely, in his speech Governor Lowe said:

‘Unless labour productivity growth is very weak, it is likely that wages will need to be growing at three point something per cent to sustain inflation around the middle of the target band. This doesn't mean that we have a target for wages growth or that wages growth is the only determinant of inflation. Rather, we are using wages growth as one of the guideposts in assessing progress towards our goal and whether inflation is sustainably in the target range.’

Fourth and finally, the RBA continues to think that expectations of early and aggressive hikes to the cash rate next year are misplaced:

‘…the latest data and forecasts do not warrant an increase in the cash rate in 2022. The economy and inflation would have to turn out very differently from our central scenario for the Board to consider an increase in interest rates next year.’

The coming data flow on wages and inflation will determine whether the RBA’s confidence on this point is justified, with this week’s Wage Price Index (WPI) data for the September quarter looking quite consistent with the RBA’s position (see previous story).

What happened:

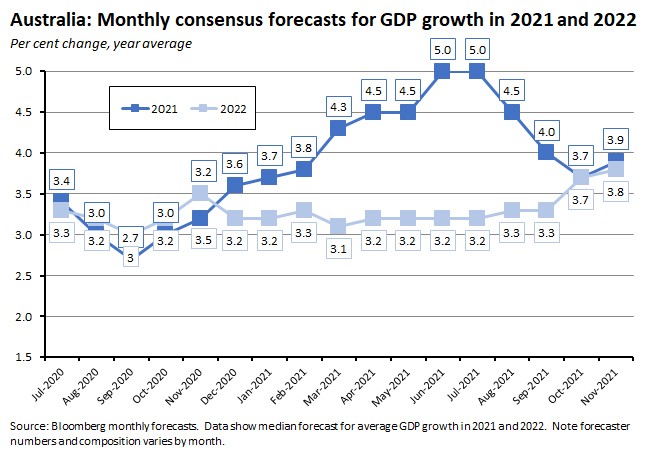

Bloomberg’s survey of economic forecasters for November 2021 brought more upgrades to median projections for real GDP growth this year and next, with the economy now expected to average 3.9 per cent growth in 2021 and 3.8 per cent growth in 2022.

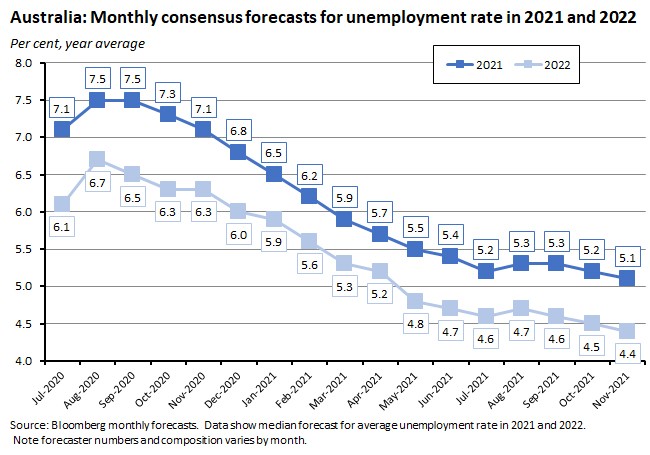

The consensus forecast for the average unemployment rate has continued to slide, down to 5.1 per cent for this year and 4.4 per cent for 2022.

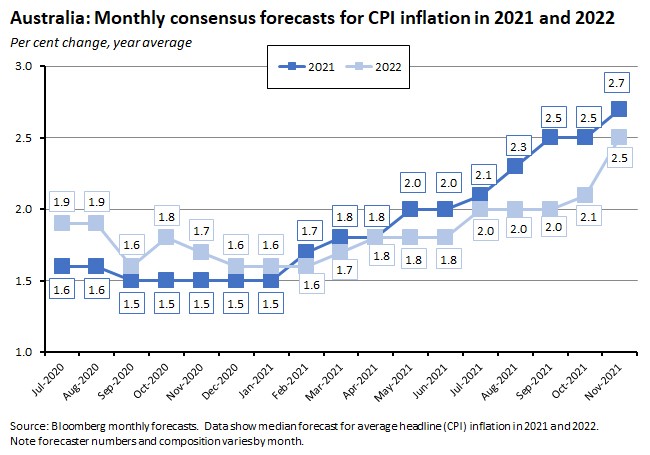

Forecasts for inflation, on the other hand, continue to rise. Headline CPI inflation is now projected to average 2.7 per cent this year and 2.5 per cent in 2023.

The median expectation for the cash rate is for it to end next year unchanged at 0.1 per cent but to then have increased to 0.75 per cent by the end of 2023 and to have risen again to one per cent by the end of the March quarter, 2024.

Why it matters:

Forecasters are now more upbeat about the near-term economic outlook. Output is expected to contract by three per cent over the September quarter (down from a predicted 3.2 per cent drop in October) while real GDP is then forecast to rise by 1.8 per cent over the quarter in Q4:2021. The labour market is expected to continue to tighten, with the unemployment rate enjoying a steady decline through to 2023, and this is predicted to see average annual wage growth rise from 1.9 per cent this year to 2.6 per cent next year and 2.9 per cent in 2023.

Headline inflation is expected to remain elevated (at three per cent in Q4:2021 and Q1:2022 and 2.7 per cent in Q2:2022) before slipping back down to 2.3 per cent by the end of next year. While there are some differences, it’s interesting to note that these numbers are not especially far away from the RBA’s forecasts in the November 2021 Statement on Monetary Policy, which have headline CPI inflation ending this year at 3.25 per cent and then ending next year at 2.25 per cent before rising to 2.5 per cent by the December quarter of 2023.

What happened:

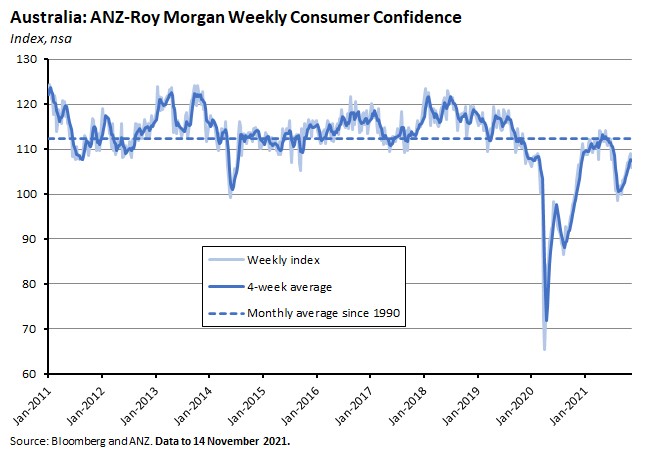

The ANZ-Roy Morgan Weekly Consumer Confidence Index fell 2.8 per cent last week.

Four out of the five subindices fell in the week to 13-14 November, with only ‘current economic conditions’ registering a small gain.

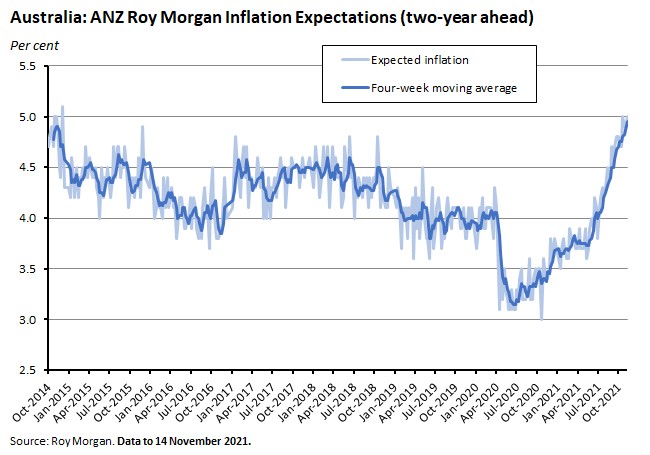

Weekly inflation expectations rose to five per cent.

Why it matters:

Consumer confidence has slipped back down to its lowest reading since early October. ANZ speculated that this could reflect the weaker-than-expected employment results last month or be a function of rising inflation expectations.

Linkage . . .

- The Modelling and Analysis for Australia’s Long-term Emissions Reduction Plan.

- Reactions from Peter Martin on why the modelling finds net zero would leave us better off and from the AFR’s John Kehoe on why ‘can-do capitalism’ looks an awful lot like socialism.

- Also from the AFR, a long read on how the Future Fund thinks about the post-COVID world order.

- And one more from the AFR, Ross Garnaut argues that COP26 was a missed opportunity for Australia to boost its chances of becoming a new low emissions energy superpower.

- Two speeches from the RBA. Luci Ellis on innovation and dynamism in the post-pandemic world and Tony Richards on the future of payments.

- Also from the RBA, Luci Ellis and Bradley Jones gave some further testimony to the Inquiry on Housing Affordability and Supply in Australia, repeating the RBA’s message that ‘the supply side of the housing market has inherently limited capacity to adjust to sharp increases in demand. There are some things that could be done to make the flow of new housing supply more responsive…speeding up planning systems to reduce general inefficiencies, improving transport infrastructure and lowering the cost of new construction. Supply-side changes of this nature would dampen the increase in prices that ensues when demand increases. But they will not undo the fact of rising demand, and they will not prevent price increases entirely.’ You can watch Ellis’s testimony here (it starts at about 11.40 on the timer).

- John Edwards with some Confessions of a Reserve Bank Board Member.

- A new BIS report on Bottlenecks: causes and macroeconomic implications.

- Tyler Cowen explains why economists should dislike higher inflation even if economic theory isn’t particularly good at coming up with compelling arguments.

- An introduction to how NFTs create value.

- The FT’s Martin Wolf selects his best economics books of (H2) 2021.

- And Robert Skidelsky reviews three biographies of economists – Hirschman, Veblen and Keynes.

- History and wealth: A reappraisal.

- The McKinsey Global Institute on the rise and rise of the global balance sheet. The report finds that for the ten countries it analyses (which collectively account for about 60 per cent of global GDP), the historic link between the growth of net worth and the growth of GDP has been broken. Over the past two decades economic growth has been lacklustre in most developed economies but balance sheets and net worth have tripled in size. Strikingly, in 2020 real estate accounted for two-thirds of net worth.

- Three podcasts to finish: the Masters in Business podcast talks to Robin Wigglesworth on the creation of the index fund; the Odd Lots podcast discusses Dutch Company ASML and its critical role in the semiconductor supply chain; and the Hexapodia podcast discusses WW2 submarine warfare, faulty torpedoes, luck and the economic lessons for opportunity and the development of managerial talent.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content