Bilateral tensions with China underscore Australia's trade vulnerability, writes AICD chief economist Mark Thirlwell.

Crises often serve to accelerate trends already apparent before the crises hit. In the case of COVID-19, an example of this is the increased strain on an already-stressed global trading system.

The travails of world trade have become a familiar theme. Last year, the US-China trade and technology war, compounded by the Brexit saga, roiled financial markets and drove policy uncertainty to record highs. As a result, international trade suffered its weakest performance since the global financial crisis (GFC).

This year, the enormously disruptive impact of COVID-19, the increasingly decrepit state of the international trade architecture and a renewal of hostilities between Beijing and Washington are threatening a dramatic deterioration in the outlook for cross-border commerce. Closer to home, Australia faces the challenge of managing an increasingly troubled relationship with its most important trading partner.

In an example of the “slobalisation” discussed in April’s column, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that world goods and services trade volumes grew by a meagre 0.9 per cent last year. Nevertheless, in January, the IMF anticipated a modest recovery in 2020, predicting trade growth of almost three per cent. But the devastating economic impact of the pandemic and the associated public health measures meant that when the IMF released new forecasts in April, it was predicting world trade volumes would plummet by 11 per cent. For its part, the World Trade Organization (WTO) worries merchandise trade could contract by anywhere between 13 and 32 per cent this year.

Actual trade data are very much a lagging indicator in the current environment, but there are early signs of the feared downturn. In March 2020, world trade volumes fell by 4.3 per cent over the previous year in their worst result in more than a decade. Forward-looking indicators — such as new export orders from multiple national purchasing managers’ surveys along with measures of sea and airborne freight and of port traffic — suggest the trade decline is poised to steepen over the second quarter in line with slumping global economic activity.

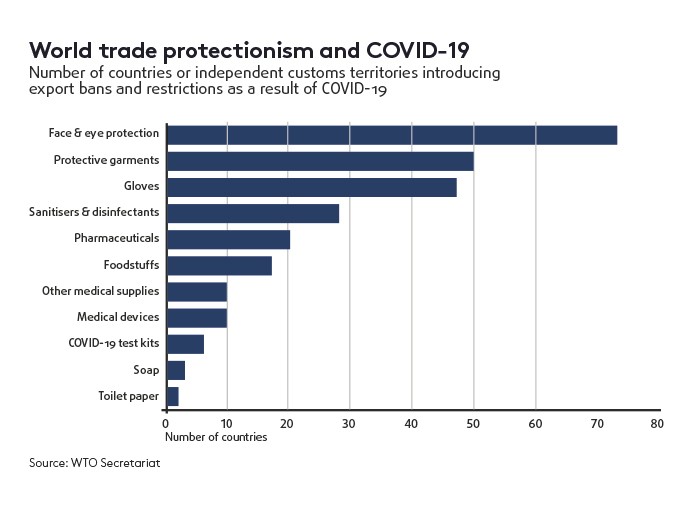

The coronavirus crisis hasn’t just been making itself felt in the volume of trade. It’s also been reshaping economic policies and attitudes as the early months of this year saw more than 80 countries respond to COVID-19 by introducing a range of export restrictions on medical and related equipment. Granted, some have since reversed course and eased restrictions. But in the meantime, many policymakers may have concluded that more national self-sufficiency is required in a post-COVID-19 world. Policymakers and businesses are considering applying that same lesson to global supply chains in general. Last year’s trade wars had already highlighted the case for diversification and localisation, or at least regionalisation, in building greater resilience. COVID-19 and the consequent disruption to China-based supply chains has amplified that message, prompting calls for the replacement of an efficiency-focused “just in time” approach to supply chain management with a potentially more robust — but also more costly — “just in case” one.

These changing incentives come in the context of an international trading system in growing disrepair. The WTO has been in trouble since its failure to deliver the Doha Round undermined its role as a vehicle for trade liberalisation. But until recently, it had retained a vital function as an overseer of the existing rules and an adjudicator of trade disputes. Now that role is also defunct, thanks in large part to a decision by the US administration to block any appointments to the seven-member Appellate Body that oversees the WTO’s appeal system (claiming bias against the US). By the end of December last year, Washington’s strategy had left the WTO with too few arbiters to staff the body. Now, either side of a trade dispute can appeal to an effectively nonexistent Appellate Body and thereby dispatch the case down a legal black hole, rendering the dispute settlement mechanism ineffective.

Compounding the narrative of a system in deep trouble, WTO director-general Roberto Azevedo announced in May that he will step down a year early. Although Azevedo has denied his decision signals the WTO is failing, declaring, “the ship is not going down”, in the same interview he also conceded, “We are doing nothing now — no negotiations, everything is stuck. There’s nothing happening in terms of regular work”. Hardly a ringing endorsement of the health of what was once a key pillar of the international economic architecture.

Although there are multiple and, in some cases, long-standing explanations for the WTO’s demise, the organisation has also been collateral damage in the geo-economic struggle between the US and China. Here, too, COVID-19 appears to have upped the ante, with both sides trading in competing conspiracy stories about the origins of the virus and Beijing recently warning of the onset of a new Cold War. Meanwhile, and despite the ongoing implementation of the “phase one” trade deal agreed between the two superpowers, the US has continued its economic decoupling from China. In late May, the US Senate approved legislation designed to make it difficult for Chinese companies to list on US stock exchanges, while the US Department of Commerce added another batch of Chinese companies and universities to its blacklist while further tightening the screws on Huawei.

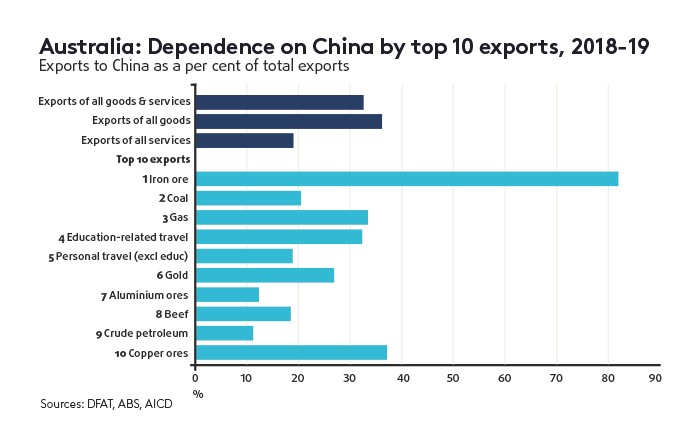

Further exacerbating this already challenging trade environment for Australian business is a deteriorating bilateral relationship between Canberra and Beijing. Rising tensions have disrupted Australian meat and barley exports and are raising depressingly familiar questions about ongoing vulnerability to geo-economic pressure at the hands of our largest trading partner.

Australia’s relatively high level of dependence on China as an export market has long been viewed as a source of potential vulnerability, although originally this was mostly couched in terms of our exposure to any sudden downturn in Chinese growth. But as Beijing has become more assertive, and increasingly willing to deploy economic pressure to secure its political and foreign policy objectives, that focus has widened to include China’s ability to wield market access as a strategic tool. Such concerns have been raised again after Chinese authorities imposed swingeing tariffs on Australian barley exports and introduced an import ban on four Australian abattoirs. The measures have been seen by some as a punitive response to Canberra’s calls for an inquiry into the origins of COVID-19, which incurred Beijing’s displeasure, although both sides have denied that this is the case.

In theory, these might be just the kind of circumstances under which a country such as Australia would turn to the WTO to seek some recourse. Unfortunately, there is now a problem with that option.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content