After last week’s focus on fiscal policy and Budget 2022-23, this week attention switched back to monetary policy. And although the April 2022 meeting saw the RBA leave the cash rate unchanged at 0.1 per cent for a 15th consecutive meeting, the headlines were all about a shift in the language used by Martin Place.

The central bank chose to excise the word ‘patient’ from the statement accompanying this week’s meeting in a move that has been widely interpreted not only as a shift to a more hawkish stance but also as indicating that the first cash rate increase since 2010 could now arrive as early as June (or even next month if market pricing is to be believed).

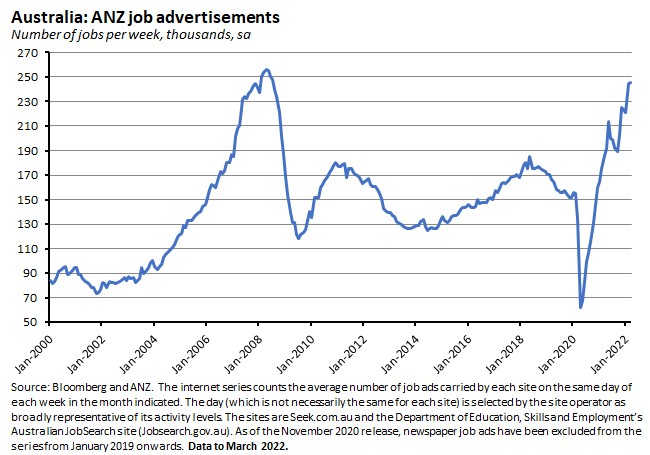

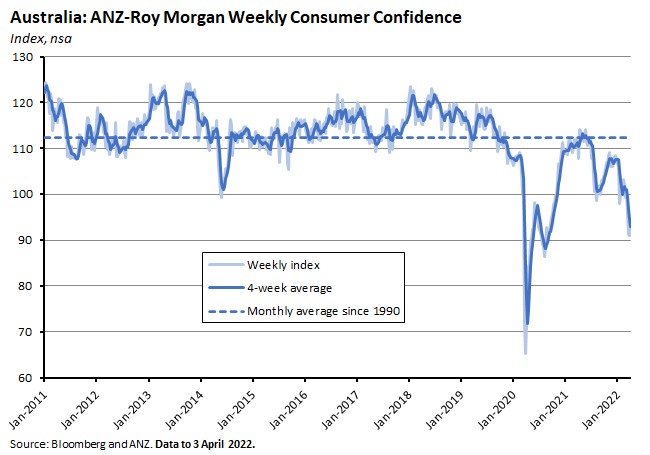

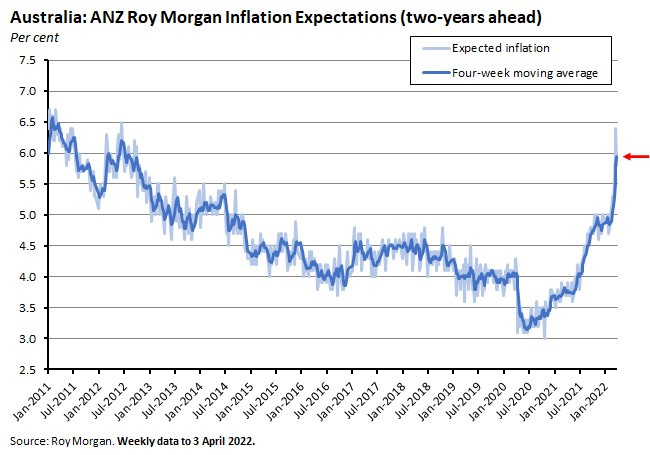

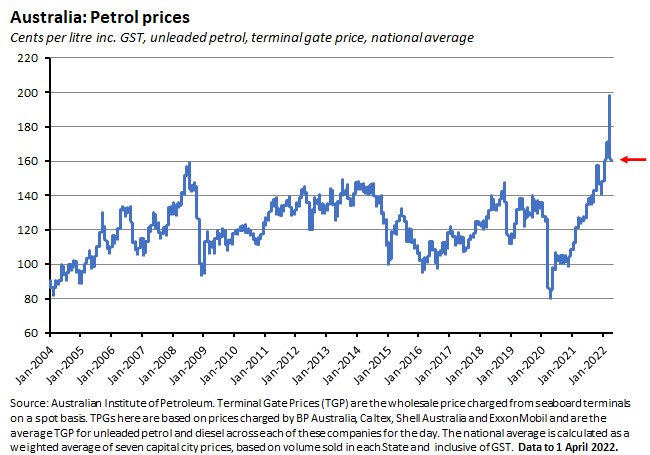

Domestic data out this week showed ANZ job ads edging up again in March as the labour market continues to demonstrate signs of tightening, although the payroll job numbers were more mixed. There was also a recovery in consumer confidence last week, which could reflect a post-budget bounce but was also likely driven by a fall in petrol prices. The latter has also produced a drop in weekly inflation expectations. We also have a roundup of the budget week’s economic numbers including an update on conditions in the housing market and a new record high for ABS job vacancies.

Turning from domestic economic conditions to the world economy, the latest global Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) results paint a mixed picture. Overall, economic activity slowed last month but remained in positive territory as the Omicron wave eased across many developed economies. At the same time, however, output slumped in a COVID-hit China and a sanctions-hit Russia. Strained supply chains and higher energy prices – particularly in Europe – are denting overall business confidence and contributing to higher input prices and overall inflationary pressures.

At the same time, minutes from the most recent US Federal Reserve FOMC meeting show that not only is the Fed now contemplating the start of Quantitative Tightening (QT) as early as next month, but that FOMC members are open to accelerating the pace of monetary policy normalisation by replacing hiking in 25b steps with larger 50bp moves. A more aggressive policy cycle and the consequent tightening in global financial conditions will place greater strains on the world economy in general and on some of those emerging market economies already struggling with the economic and financial consequences of the Ukraine war in particular.

Finally, this week’s linkage selection includes new record forecasts for Australian resource exports, the PBO’s budget snapshot, a new RBA chart pack, lots on the potential economic and financial implications of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, another sobering assessment from the IPCC and a collection of podcasts that make the case against crypto, examine the use of sanctions as a weapon of war, quiz Larry Summers on US inflation prospects and consider the role of commodities and commodity traders in the world economy.

RBA messaging is sounding more hawkish on inflation

At its meeting on 5 April 2022 the RBA decided to leave the cash rate target unchanged at 10bp. However, most attention has been focused not on the fully anticipated decision to leave the cash rate as it was for a 15th consecutive meeting, but instead on the disappearance of the word ‘patient’ from the accompanying statement. That change has been widely interpreted as giving Martin Place the flexibility to start increasing the cash rate as early as the meeting on 7 June this year.

Why the fuss? Well, after last month’s March RBA meeting, the concluding paragraph of the central bank’s statement said that:

‘The Board will not increase the cash rate until actual inflation is sustainably within the 2 to 3 per cent target range. While inflation has picked up, it is too early to conclude that it is sustainably within the target range. There are uncertainties about how persistent the pick-up in inflation will be…The Board is prepared to be patient as it monitors how the various factors affecting inflation in Australia evolve.’ [emphasis added]

That same final sentence had also appeared following the first meeting of this year in the February statement and a variant had also appeared in the final December statement of last year, which said that:

‘The Board will not increase the cash rate until actual inflation is sustainably within the 2 to 3 per cent target range…This is likely to take some time and the Board is prepared to be patient.’ [emphasis added]

RBA watchers have seized on the difference between this earlier monetary policy guidance and the final paragraph in this week’s statement, with the latter reading as markedly less diffident on the inflation outlook:

‘The Board has wanted to see actual evidence that inflation is sustainably within the 2 to 3 per cent target range before it increases interest rates. Inflation has picked up and a further increase is expected, but growth in labour costs has been below rates that are likely to be consistent with inflation being sustainably at target. Over coming months, important additional evidence will be available to the Board on both inflation and the evolution of labour costs. The Board will assess this and other incoming information as its sets policy to support full employment in Australia and inflation outcomes consistent with the target.’

Any mention of ‘patience’ has been abolished. Moreover, there is also a recognition that not only has inflation already picked up, but that a further increase is now expected.

The statement also says that additional evidence on inflation and labour costs will be available over ‘coming months’, suggesting that the RBA will be keeping a close eye on the March quarter Consumer Price Index (due 27 April) and Wage Price Index (due 18 May). That particular phrasing has been interpreted as giving the RBA the flexibility to start ‘normalising’ the cash rate as early as the June meeting, but not as early as next month. If so, that would be the first increase in the cash rate since November 2010. It would also come hot on the heels of an election.

Although the central bank is still cautious on wage growth

All that said, the RBA still sounds more cautious on inflation than the financial market consensus. For example, while the statement does concede that ‘inflation has increased in Australia’ and that higher prices for petrol and other commodities ‘will result in a further lift in inflation over coming quarters,’ it also points to three ongoing sources of uncertainty on the inflation front: ‘the speed of resolution of the various supply-side issues, developments in global energy markets and the overall evolution of labour costs.’ And on that final point in particular, the RBA’s longstanding circumspection with regard to the labour market is still with us. The text in the final paragraph cited above includes the comment that ‘growth in labour costs has been below rates that are likely to be consistent with inflation being sustainably at target’ and earlier in the statement, while acknowledging that the labour market has continued to tighten, the text also notes that the pick-up in aggregate wage growth to date is still ‘only around the relatively low rates prevailing before the pandemic’ and that although wages are expected to continue to rise from here, the central bank’s base case is still for this to be a gradual process, albeit one subject to the potential for a surprise to the upside.

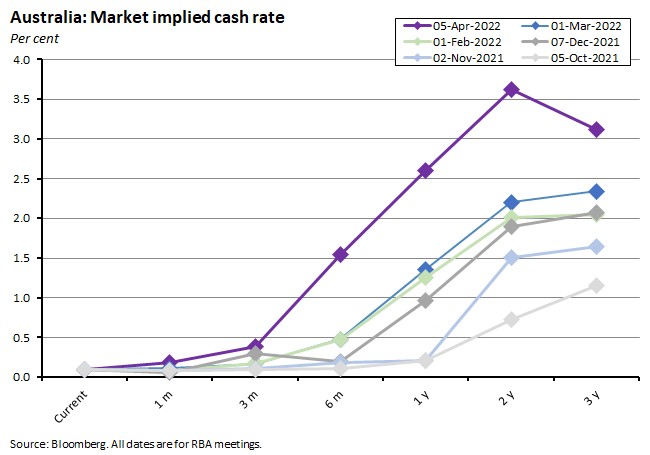

Which means that – even after this week’s significant shift in central bank rhetoric – it still feels like there is a considerable gap between what the RBA is saying about the likely path of monetary policy normalisation and what markets are expecting. At the time of writing, markets were predicting that a cash rate hike as early as next month was more likely than not, while cash rate futures implied at least eight rate hikes by the December meeting of this year plus a decent chance of a ninth, with a cash rate north of 2.2 per cent by year-end. Look further out, and markets see the cash rate back above 3.5 per cent in two years’ time, a level that it hasn’t reached since June 2012.

At the end of last year, the ratio of household debt to disposable income stood at close to a record high of 186.2 per cent. But low interest rates meant that the ratio of interest payments on that debt to disposable income was only a modest 5.2 per cent. If market forecasts are right, and in the absence of a surge in income growth, more than 350bp of rate increases over the next two years would see a significant increase in the burden of debt service for the household sector.

Meanwhile, global growth slowed last month

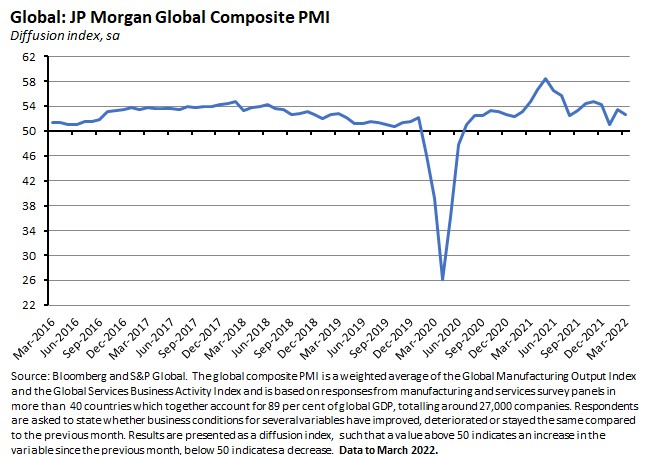

The J P Morgan Global Composite PMI (pdf) fell 0.8 points from 53.5 in February to 52.7 in March. That still left the index in expansionary territory for a 21st consecutive month, but it also confirmed that the global economy lost some momentum at the end of the first quarter of this year. Output growth slowed in both the manufacturing and services sectors, with the former suffering more: manufacturing output growth was the weakest recorded during all 21 months of the current expansionary phase.

The March PMI results show contrasting forces at work in the global economy. On the one hand, the easing of the Omicron wave across many developed markets has allowed services activity there to continue to strengthen and the overall rate of job creation to match the highest recorded since the end of 2007. On the other hand, China’s struggle to manage the virus meant that country saw a large decline in activity towards the end of Q1, with the manufacturing PMI falling from 50.4 in February to 48.1 in March while the services Business Activity Index slumped from 50.2 to 42 over the same period. And in Russia, the impact of sanctions and the war in Ukraine saw the manufacturing PMI tumble from 48.6 in February to 44.1 in March (the sharpest fall in the past two years) while the Russian services Business Activity Index plummeted from 52.1 in February to 38.1 last month in the largest decline seen since the first months of the pandemic.

At the global level, the combination of increased geopolitical uncertainty, rising inflationary pressures and strained supply chains saw the survey’s measure of business optimism fall to a 15-month low despite the ongoing rise in activity. The Omicron wave in Asia and war in Europe have contributed to a worsening in global supply chain performance, with manufacturers in particular reporting an increase in average delivery times, and with Europe hit hardest. In contrast, manufacturers in the United States reported an easing in supply chain conditions last month, with the incidence of delays falling to a 14-month low.

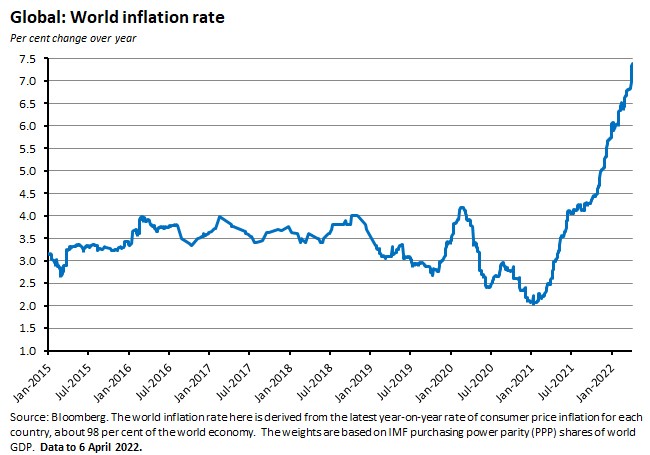

Disrupted supply chains and higher energy prices following the Russian invasion of Ukraine have also contributed to more inflationary pressures. Rates of increase in both input costs and output charges accelerated last month while backlogs of work rose to the greatest extent seen in almost 18 years. Once again, conditions in Europe were particularly hit, while there was a slight easing of some price pressures in the United States. Bloomberg’s daily global inflation tracker currently has world inflation running at close to 7.5 per cent.

And the Fed has flagged the start of Quantitative Tightening

Two final points on global economic conditions.

First, the release of the minutes from the 15-16 March Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting – remember, this was the meeting at which the Fed increased the Fed Funds rate by 25bp in the first increase in the policy rate since 2018 – revealed that the FOMC had:

‘…agreed that reducing the size of the Federal Reserve's balance sheet would play an important role in firming the stance of monetary policy and that they expected it would be appropriate to begin this process at a coming meeting, possibly as soon as in May.’

The minutes also confirmed that, but for the war in Ukraine, the Fed would have moved more aggressively last month, reporting that:

‘Many participants… would have preferred a 50bp increase in the target range for the federal funds rate at this meeting. A number of these participants indicated, however, that, in light of greater near-term uncertainty associated with Russia's invasion of Ukraine, they judged that a 25bp increase would be appropriate at this meeting. Many participants noted that one or more 50bp increases in the target range could be appropriate at future meetings, particularly if inflation pressures remained elevated or intensified.’

In other words, expect a combination of Quantitative Tightening (QT) and the possibility of one or more super-sized 50bp rate hikes ahead, as the Fed ramps up the pace of monetary policy normalisation.

QT is basically the opposite of Quantitative Easing (QE). During QE, the central bank buys government bonds and other assets that adds liquidity to the financial system and also leads to an increase the size of its balance sheet. As those bonds mature, the central bank reinvests the proceeds into new bonds. QT occurs when the central bank reverses policy direction and starts to shrink its balance sheet. It can do this in a couple of ways. The passive version is to simply allow the bonds it holds to mature (‘roll-off’) and not replace them with new bonds, gradually shrinking its balance sheet over time. Alternatively, active QT involves the central bank selling the bonds it has acquired, thereby sucking liquidity out of the financial system in a more aggressive manner.

Just as QE is supposed to bring down the yields on longer-term debt, boost liquidity and signal looser monetary conditions, so QT is expected to lift yields, reduce liquidity and indicate a tighter policy stance. The big unknown is, by how much? While the world has become (relatively) used to episodes of QE, the experience with QT is much more limited. The Fed’s last effort started in 2017 and ended in 2019 with a bout of money market volatility that saw the effective Fed Funds rate breach the top of the Fed’s target band and ultimately persuade the central bank to start buying bonds again. The Fed had already indicated this week – via remarks from vice chair Lael Brainard – that the pace of QT would be considerably faster than the 2017-19 experience. The minutes confirmed this and said that the approach to QT would see the Fed reduce its holdings of securities ‘primarily by adjusting the amounts reinvested of principal payments received’ (passive QT). Principal payments received from securities held by the Fed would only be reinvested to the extent they exceeded monthly caps and according to the minutes, participants ‘generally agreed that monthly caps of about US$60 billion for Treasury securities and about US$35 billion for agency Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) would likely be appropriate.’ The plan, then, is for the Fed to remove up to US$95 billion of assets each month from its balance sheet, which is currently around US$9 trillion in size. The minutes also noted that the Fed will consider directly selling some of its holdings of MBS (active QT) once the process of balance sheet run-off was ‘well underway’.

Second, a more forceful tightening in global financial conditions coming on top of the commodity price disruption that has been exacerbated by war in Ukraine along with another wave of disruptions to world trade and supply chains is likely to be bad news for financial stability in some already-exposed emerging markets. Markets from Sri Lanka (where there have been widespread protests over foods and power shortages and soaring inflation, and where there are fears that the country is on the brink of a sovereign default) to Egypt (hit by soaring food and energy prices and the loss of Russian and Ukrainian tourists) were already suffering and economists at the World Bank warned recently that the world could soon see the largest spate of debt crises in developing economies in a generation.

What else happened on the Australian data front this week?

Job Ads

ANZ Australian Job Ads edged up by 0.4 per cent over the month in March to stand at 245,891. That follows an upwardly revised 10.9 per cent monthly gain in February and leaves the number of ads 57.5 per cent higher than pre-pandemic (January 2020) levels.

Payroll jobs

The latest ABS estimates for weekly payroll jobs and wages show jobs up 0.2 per cent over the fortnight to 12 March 2022 but down 0.6 per cent over the past month. Total wages paid over the same period were down 0.7 per cent and 1.7 per cent, respectively. The number of payroll jobs is now four per cent higher than at the start of the pandemic, in mid-March 2020.

The Bureau noted that the pattern of change in payroll jobs – with a fall in the second half of February followed by a slight increase in the first half of last month – coincided with adverse weather conditions and flooding in New South Wales and Queensland in late February along with the ongoing influence of Omicron and the easing of public health restrictions. The net impact is that the increase in payroll jobs over the first months of this year has been weaker than the gains in employment seen in both 2020 and 2021.

Consumer confidence

The ANZ-Roy Morgan weekly index of consumer confidence rose 2.5 per cent last week, bringing to an end a run of three consecutive weekly falls. All five subindices also rose over the week. That could reflect a positive reaction to last week’s budget, but it could also be driven by a reversal in inflation concerns.

The rebound in confidence was correlated with a fall in inflation expectations which likewise broke a three-week run of increases, falling back to 5.8 per cent last week from 6.4 per cent the week before.

Fuel prices continue to be a big part of the story here, with a drop in global oil prices earlier this month having fed through into a fall in petrol prices. There’s also scope for the reduction in the petrol excise announced in Budget 2022-23 to lead to a further decline (the cut official took effect from midnight on budget night, but the assumption is that it will take up to two weeks before it is generally passed on).

International trade in goods and services

The ABS said that Australia ran a trade surplus of $7.5 billion in February this year (seasonally adjusted), down from January’s $11.8 billion surplus. Exports of goods and services were largely flat over the month at $48.8 billion with the narrowing in the surplus driven by a 12 per cent rise in imports to $41.3 billion.

That increase in imports was driven in part by a 17 per cent jump in the value of intermediate and other merchandise goods, with increases in processed industrial supplies and fuels and lubricants. The other driver was another 17 per cent jump, this time in imports of consumer goods. In this case, the largest dollar increases included non-industrial transport equipment and textiles, clothing and footwear. Overall, the rise in imports in February is consistent with a pick-up in consumer spending and with the rising cost of inputs including fuel.

And what happened last week?

The weekly note took a break for budget week, so below is a quick summary of some of the data releases we missed including a set of releases on the housing market plus numbers on job vacancies, retail sales, and finance and wealth.

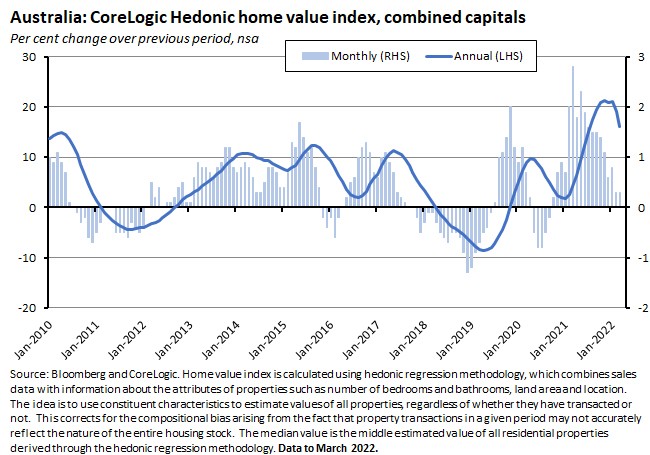

The housing market

Starting with housing, CoreLogic said that its national home value index (HVI) was up 0.7 per cent over the month in March 2022, following a 0.6 per cent rise in February. In annual terms, the pace of growth fell to 18.2 per cent last month, the first time it has dropped below 20 per cent since last August. Meanwhile, monthly growth in the combined capitals index was unchanged at a relatively subdued 0.3 per cent while annual growth slipped to 16.3 per cent.

Values fell over the month in Sydney (down 0.2 per cent) and Melbourne (down 0.1 per cent) but rose across the other capital cities and in regional Australia.

According to CoreLogic, the housing market has now transitioned from what was a strong and broad-based rise to a multispeed market, with Sydney and Melbourne at the weak end of the spectrum and Brisbane and Adelaide at the opposite end. The data provider also said that rising fixed-term mortgage rates, declining affordability, higher living costs, higher supply coming on to the market and softening consumer sentiment all mean that the outlook for values is skewed to the downside, although continued low unemployment and rising employment, a pending return of migration and more incentives for first home buyers should offset some of that risk.

Sticking with the housing market, the ABS reported that new lending commitments for housing fell 3.7 per cent (seasonally adjusted) over the month in February this year after having hit a record high in January. New lending was still up 12.6 per cent over the same month last year. Lending to owner occupiers fell 4.7 per cent over the month and also slipped by one per cent over the year, while lending to investors was down 1.8 per cent month-on-month. That was the first monthly decline in investor lending since October last year, but it followed a record high in January and was still up almost 56 per cent year-on-year. The Bureau also noted a shift in the mix of fixed and variable-rate lending to households, with the share of fixed-rate loans dropping to 28 per cent as borrowers responded to higher rates. That proportion is down from a peak of 46 per cent in July 2021.

The ABS also said that the seasonally adjusted estimate for the number of total dwellings approved surged 43.5 per cent over the month in February this year, bouncing back from a 43.3 per cent Omicron-influenced drop in January. That left approvals down 7.8 per cent in annual terms. Approvals for private sector houses rose 16.5 per cent over month (but fell 27.4 per cent year-on-year) while approvals for private sector dwellings excluding houses jumped 78.3 per cent over the month and 25.5 per cent over the year.

The RBA said that total credit for housing rose 0.6 per cent over the month in February, a slight slowdown from January’s 0.7 per cent growth rate. In annual terms, credit was up 7.8 per cent. Total credit growth was 0.6 per cent over the month and 7.9 per cent over the year.

National Accounts – Finance and Wealth

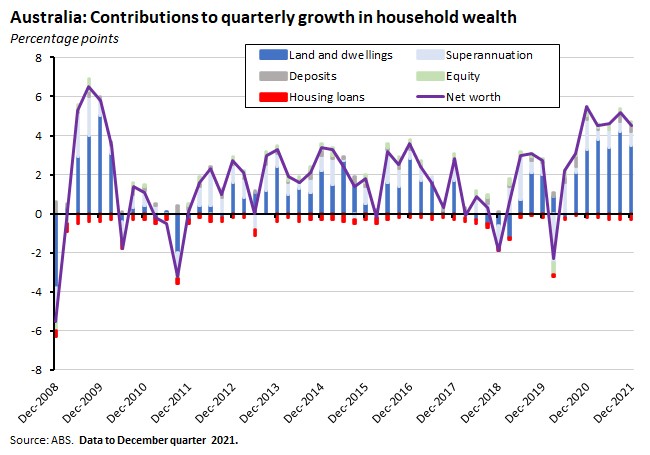

Related, the ABS reported that total household wealth rose 4.5 per cent ($628 billion) in the December quarter of last year to reach a record high of $14,677 billion. Wealth per capita at $566,541 also set a new record.

Rising property prices again drove the increase in household wealth, accounting for 3.5 percentage points of that 4.5 per cent quarterly growth rate. Increases in superannuation balances (which reflected both the recovery in the labour market and the increase of the superannuation guarantee from 9.5 per cent to 10 per cent from 1 July 2021) contributed a further 0.7 percentage points.

Job vacancies

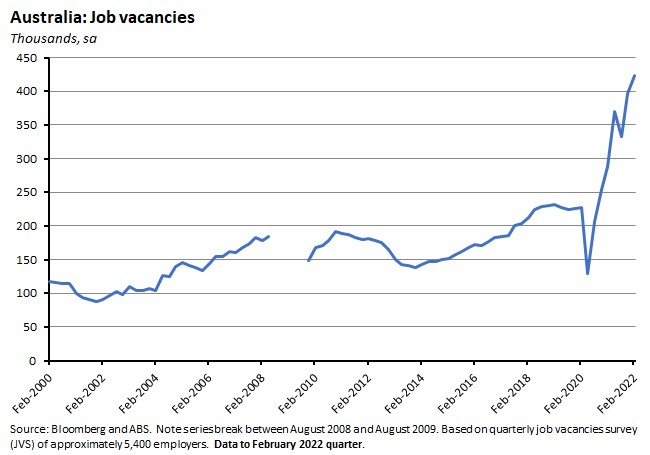

According to the ABS, there were 423,500 job vacancies in Australia in February 2022, an increase of almost seven per cent (seasonally adjusted) from the November 2021 reading, a 46.6 per cent increase over February 2021, and a new record high. Public sector vacancies rose 8.6 per cent over the quarter while private sector vacancies were up 6.7 per cent. The total level of vacancies is now 86 per cent higher – about 200,000 more – than in February 2020, before the start of the pandemic.

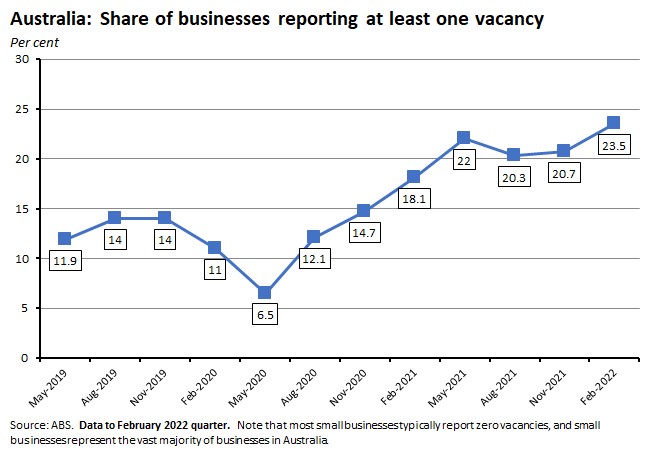

The ABS also said that the share of businesses reporting at least one vacancy rose to 24 per cent in February 2022 from 21 per cent in November 2021. Pre-pandemic, just 11 per cent of businesses were reporting at least one vacancy. The increase in vacancies has been particularly pronounced in those industries most directly affected by the pandemic, including accommodation and food services, arts and recreation services and rental, hiring and real estate services.

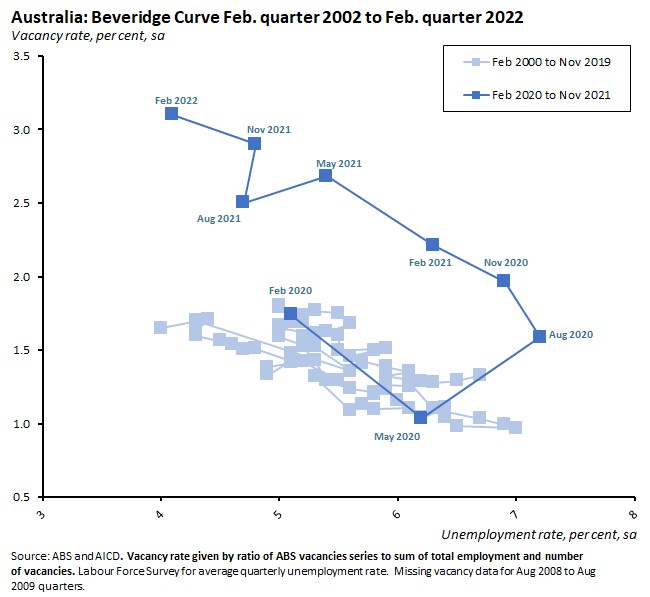

The relationship between the vacancy rate and the unemployment rate (the so-called Beveridge Curve we discussed here) continues to show a marked outward shift. Typically, that’s taken as an indicator of a decline in the efficiency with which the labour market is matching workers with jobs and/or of a rise in skill mismatches. But it is also consistent with the current rise in the participation rate and the rapidity of recent shifts in the labour market.

Retail sales

The ABS said that retail trade rose 1.8 per cent over the month (seasonally adjusted) in February 2022 to be 9.1 per cent higher than in February 2021. That took the level of retail sales to their second highest on record (after November 2021). Sales gains were particularly strong for most discretionary spending industries as lockdowns ended and public health restrictions were eased, with turnover for cafes, takeaways and restaurants rising 9.7 per cent over the month to reach a new record high. There were also sizeable gains for clothing, footwear and personal accessory retailing (up 11.2 per cent) and department stores (up 11.1 per cent).

Business conditions and sentiments

According to the ABS March 2022 survey of busines conditions and sentiments, 39 per cent of all businesses expect the price of their goods and services to increase more than usual and 40 per cent have reported an increase in operating expenses over the past month (up from 24 per cent at the same time last year). Of those businesses reporting that they plan to increase their prices over the coming month, the majority indicated that rising fuel or energy prices (88 per cent) and increases in the costs of products or services used by the business (also 88 per cent) were contributing factors. That compared to 28 per cent citing increases in staff wages or salaries and 23 per cent citing an increase in other staff-related costs.

The ABS also reported that 41 per cent of businesses were currently experiencing supply chain disruptions, up from 37 per cent in February but below January 2022’s 47 per cent rate. At the same time, 19 per cent of employing businesses said they had staff unavailable due to COVID-19 related issues, up from 15 per cent in February.

Other things to note . . .

- The latest edition of Resources and Energy Quarterly. Australia’s resource and energy export earnings will set a new record in 2021-22, thanks to soaring values of LNG, thermal coal and metallurgical coal exports, with earnings jumping 33 per cent to an all-time high of $425 billion before falling back to $370 billion (in real terms) in 2022-23 and then levelling out at $263-293 billion over the rest of the forecast period.

- The Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO)’s 2022-23 Budget Snapshot.

- The RBA’s April 2022 Chart Pack.

- Graeme Dobell examines the (geo)politics and (geo)economics of Australia’s election.

- Fixed or variable rate mortgage?

- Grattan explainer on cutting fuel excise.

- John Freebairn on natural disasters and government policy challenges.

- The Productivity Commission announced the Closing the Gap Review.

- The ABS on measuring excess mortality in Australia during the pandemic. According to the Bureau, there were over 5,000 deaths more than expected in Australia during 2021, although only a small number of weeks over the year recorded statistically significant excess deaths. In contrast, there were 1,734 fewer deaths than expected in 2020. By way of comparison, there were 3,630 more deaths than expected in 2017, in that case driven by a severe flu season.

- In the AFR, Richard Holden argues that if Australia is serious about achieving faster productivity growth, we need to do better on funding R&D and universities.

- Also in the AFR, Jim O’Neill announces the end of the global savings glut theory of low interest rates.

- Vox EU is hosting a debate on the economic consequences of the war in Ukraine. Recent contributions include a look at sanctions and the international monetary system and the potential for persistent shifts in global supply chains.

- Tooze on how the war has already changed the world economy.

- European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) assessment of the implications of the war for regional growth.

- A two-part FT series on the weaponisation of finance starts off with a look at the ‘shock and awe’ of sanctions and then considers the consequences for the future of the US dollar.

- Related, the Economist reckons the war won’t challenge the dominant role of the US dollar.

- But Credit Suisse’s Zoltan Pozsar has an alternative take - money, commodities and Bretton Woods III (pdf).

- The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report offers a sobering assessment of the prospects for limiting global warming: Climate Change 2022.

- The IMF proposes a global strategy to manage the long-term risks of COVID-19.

- Also from the Fund, a staff note looking at labour market tightness in advanced economies.

- Related, US Fed research says ‘great resignations’ are a common feature of rapid economic recoveries.

- Bloomberg on the big squeeze in the nickel market.

- Apologies for suggesting not one, not two but three podcasts from the same source. But all three of these are worth a listen: Ezra Klein talks to Dan Olson about the case against crypto; stand-in and Klein soundalike Roge Karma talks to Nicholas Mulder on the rise of sanctions as a tool of modern war (Mulder’s book on the same topic is cropping up on must-read lists everywhere), and Klein (again) talks to Larry Summers about US inflation.

- Finally, for those who’d like a non-Klein podcast, readers might remember that my book of the year in 2021 was Blas and Farchy’s The world for sale. Their perspective on the world of commodities is even more interesting given the current turmoil in global commodity markets and you can hear both authors talk on this Intelligence Squared podcast.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content