Australia’s real GDP rose 3.1 per cent over the December 2020 quarter, comfortably beating market expectations, as the economy continued to enjoy a household-led recovery. Despite last week’s bond market ructions, the RBA stuck to its guns this week, left all its major policy settings unchanged at its March meeting, and confirmed once more that it doesn’t expect to adjust the cash rate ‘until 2024 at the earliest.’ Australia delivered another large current account surplus in Q4:2020 followed by a new record trade surplus in January 2021.

Retail turnover was up just 0.5 per cent over the month in January this year but was more than 10 per cent higher than in January 2020. The number of payroll jobs was unchanged over the past fortnight. ANZ jobs ads rose more than seven per cent over February to be up more than 13 per cent compared to pre-pandemic levels. CoreLogic reported that Australian national home values in February rose at their fastest monthly rate since 2003. New loan commitments for housing surged in January. Weekly consumer confidence rose over the past week, breaking a run of three consecutive weeks of falling sentiment.

This week’s readings include yet more data from the ABS, the potential cost of our not being a member of the ‘climate club’, Australia’s financial regulators’ sanguine take on the housing market, how maths destroyed English football, lots of readings on the inflation debate currently gripping markets, democracy under siege, chart-crimes, and reimagining capitalism.

Many thanks to everyone who said ‘hello’ at this week’s AGS, I really appreciated all your feedback on the weekly note and the podcast. And my apologies for another big, bumper set of data and charts this time for those who prefer to get straight to the reading selection! In my defence, the GDP data only rolls out once a quarter and I’ve trimmed back some of the other analysis…

And stay up to date on the economic front with our AICD Dismal Science podcast.

What I’ve been following in Australia:

What happened:

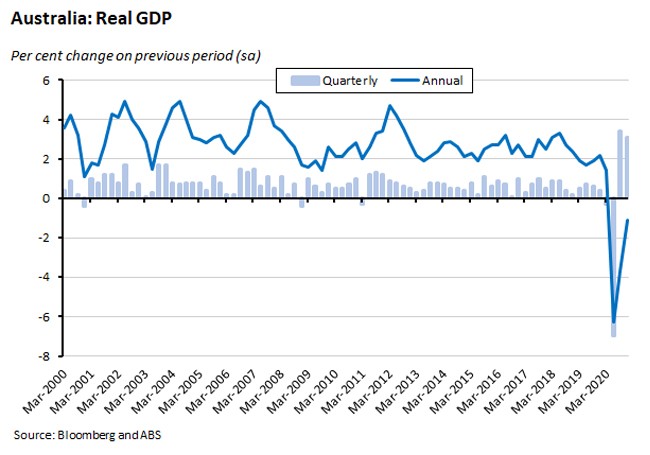

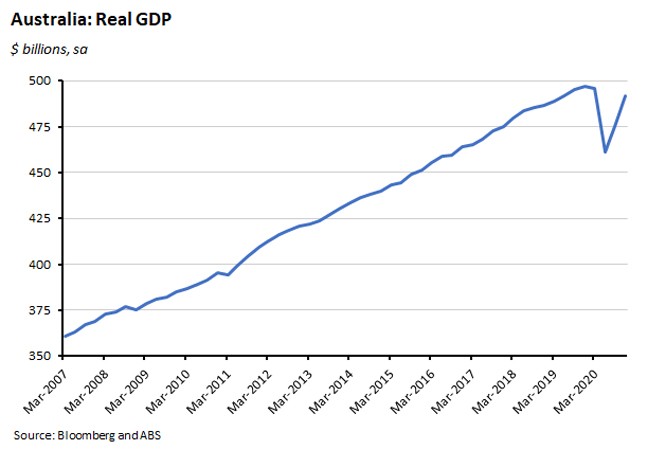

The ABS said that in the December quarter of last year, Australian real GDP grew 3.1 per cent (seasonally adjusted) over the previous quarter to be down just 1.1 per cent relative to Q4:2019.

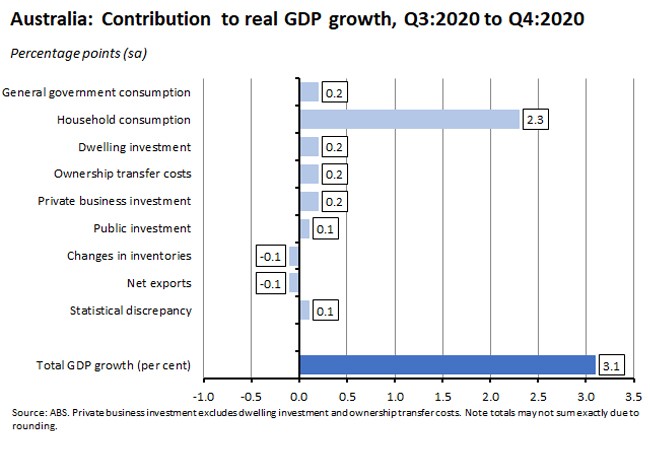

In expenditure terms, growth in the fourth quarter was led by household consumption, which contributed 2.3 percentage points to the overall growth rate. The surge in the housing market (see stories below) also made its mark, with dwelling investment and ownership transfer costs each contributing 0.2 percentage points. Private business investment added a further 0.2 percentage points, which reflected a large increase in spending on machinery and equipment, but spending on non-dwelling construction fell. There was also a small positive contribution from public investment and about twice as large a contribution from government consumption. Net exports, on the other hand, were a slight drag on growth as higher activity sucked in more imports.

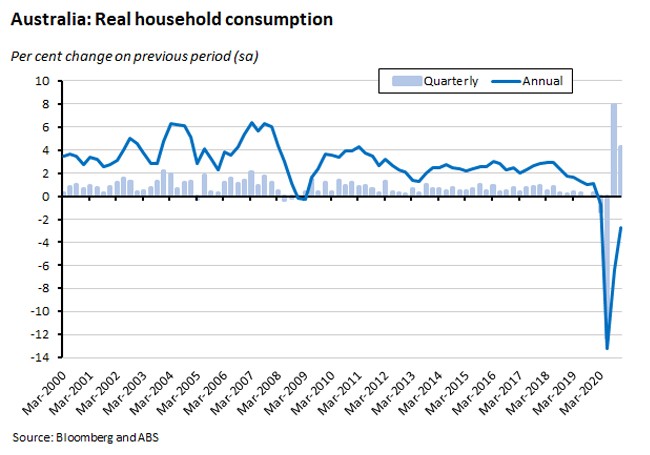

In the case of households, after growing by a record 7.9 per cent over the quarter in Q3, Q4 saw real household consumption rise by a further 4.3 per cent (seasonally adjusted). Even so, that still left consumption down 2.7 per cent relative to the same quarter in 2019.

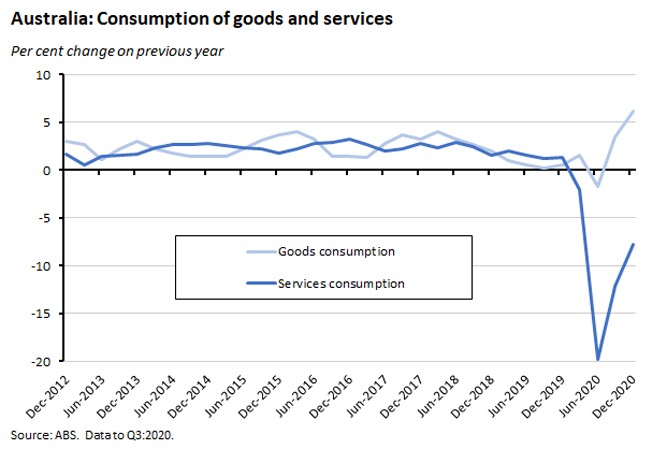

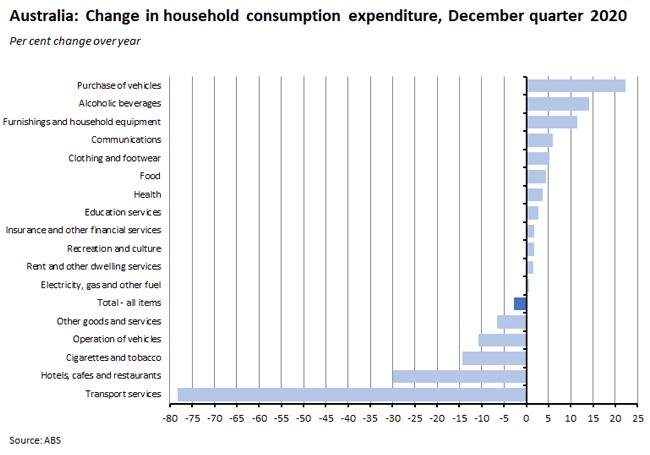

Household spending on goods rose 2.8 per cent over the quarter and was up 6.2 per cent in annual terms. This included a record 31.8 per cent jump in the purchase of vehicles, which the ABS says was powered by the combination of an increase in household disposable income alongside shifting spending patterns as money was reallocated from items such as international travel. Spending on services were also up over the quarter, rising 5.2 per cent, but in contrast to spending on goods, expenditure on services was still a substantial 7.8 per cent lower than in Q4:2019.

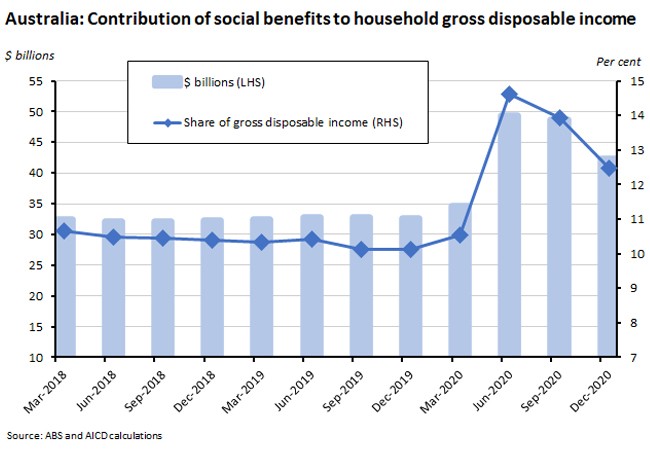

While the pace of annual growth in real household disposable income fell back in the December quarter, it still remained elevated relative to recent years.

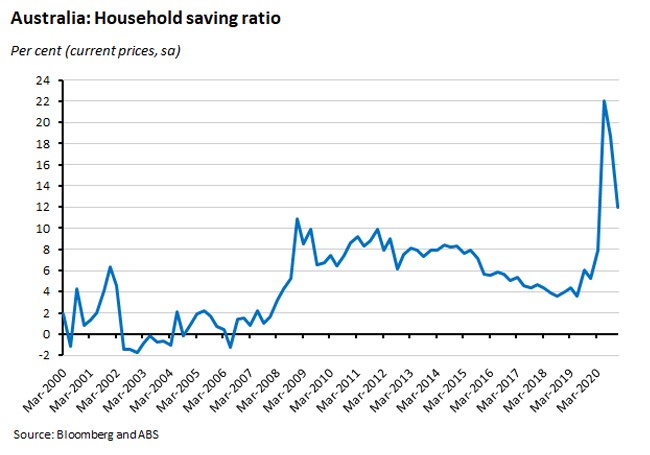

After having peaked at 22 per cent in the June quarter, the household saving ratio fell from 18.7 per cent in the September quarter to a still high 12 per cent in the December quarter.

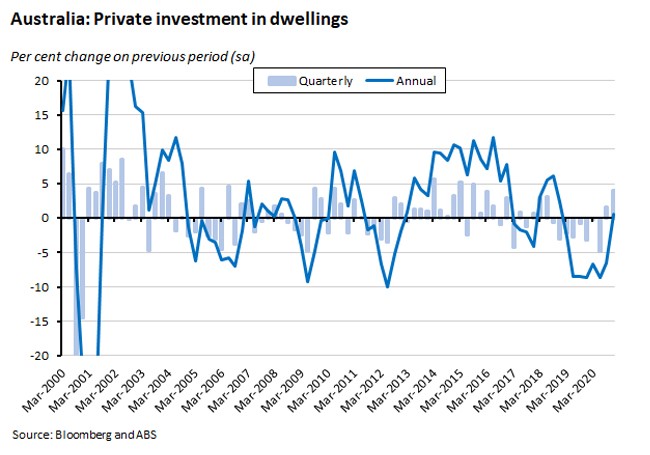

Housing market strength was reflected in a 4.1 per cent increase in dwelling investment over the quarter, which brought annual growth (of 0.6 per cent) to break a run of seven consecutive quarters of year-on-year declines. The more than 15 per cent jump in ownership transfer costs, which captures stamp duty as well as the fees paid to lawyers, fees and commissions paid to real estate agents and auctioneers and local government charges, was another sign of the increase in housing market activity over the final quarter of last year.

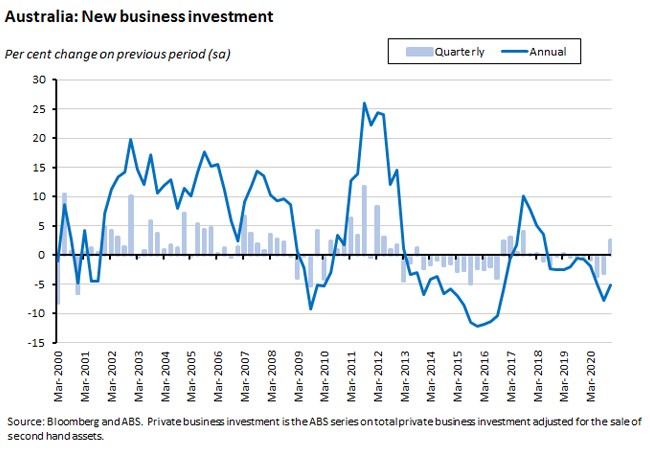

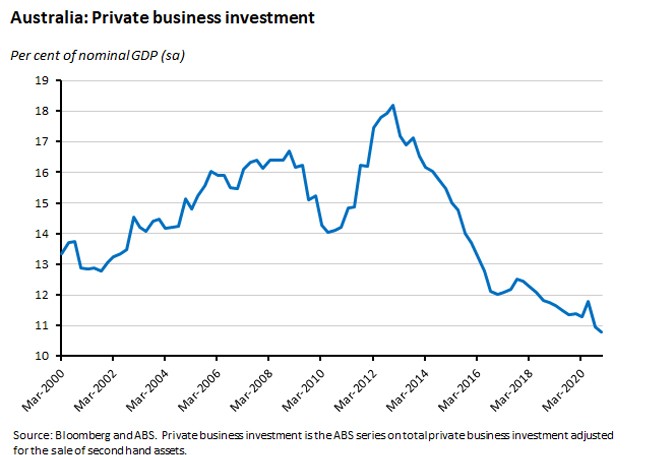

Private new business investment also displayed some signs of recovery in the December quarter, although in annual terms spending remained down relative to 2019.

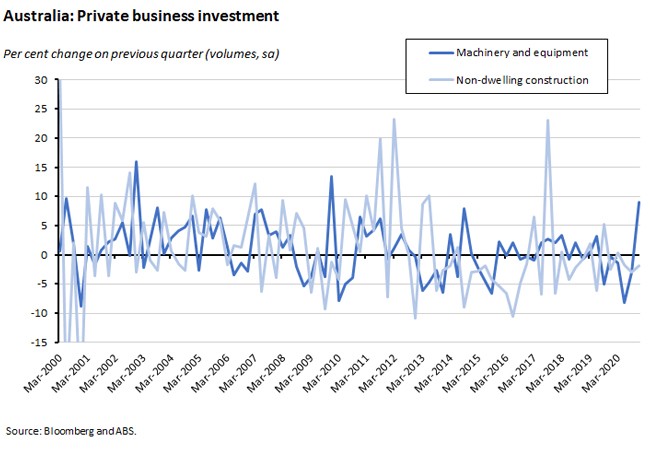

Investment in machinery and equipment jumped 8.9 per cent over the quarter in a positive response to the government’s temporary full-expensing policy, while in contrast, non-dwelling construction fell again, dropping 1.9 per cent in quarterly terms.

As a share of nominal GDP, business investment slipped yet lower in the December quarter.

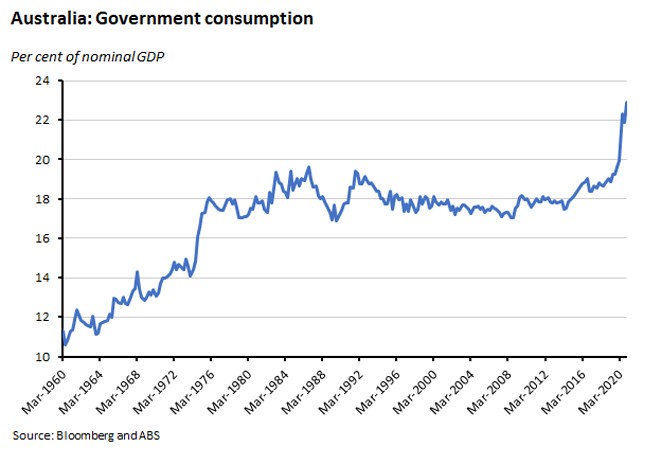

Government consumption as a share of GDP rose again.

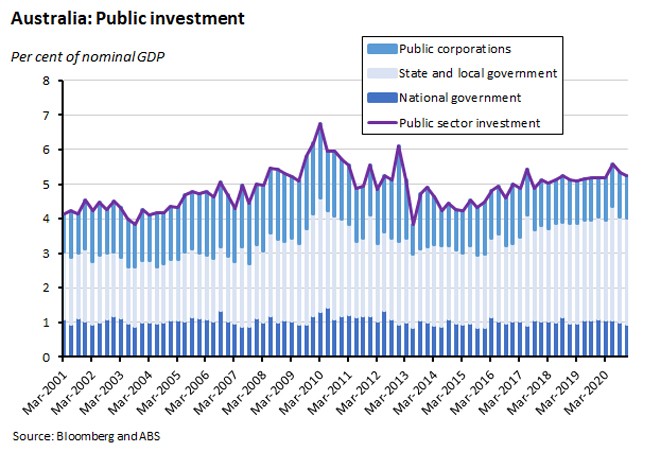

But public investment fell back slightly.

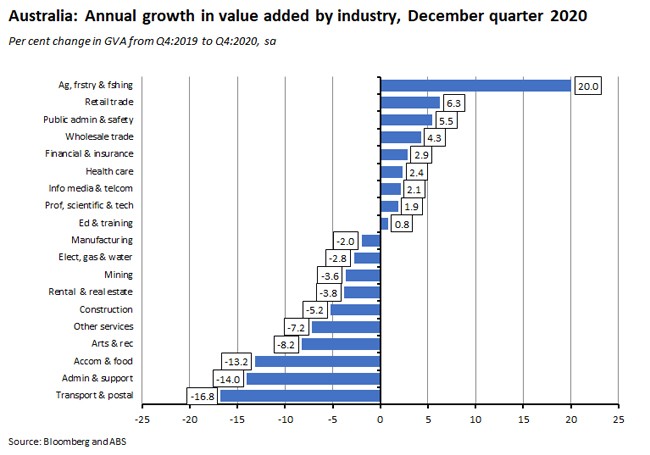

On the production side of the national accounts, growth over the December quarter saw gross value added (GVA) in agriculture, forestry and fishing surge by 26.8 per cent, pushing the annual rate of growth in GVA up to 20 per cent. This mainly reflected a 22.5 per cent increase in agriculture GVA over the year, marking the largest rise since 2008, as grain output soared by 84.4 per cent, reflecting the end of the drought. Retail and wholesale trade also did relatively well through the pandemic, and there was, of course, a boost in activity related to public administration and safety services.

In contrast, mining GVA fell 3.6 per cent over the year in what was that industry’s weakest result since 2003. The fall was driven by a 12.4 per cent drop in GVA for coal mining, with the ABS pointing to a combination of factors including adverse weather events leading to the temporary closure of mines and disruption of coal production along with global Industrial shutdowns in response to the pandemic and changes to international import policies which led to reduced demand for Australian coal. The decline was partly offset by a 2.1 per cent rise in iron ore mining.

The biggest declines in through the year GVA were in transport, postal and warehousing (down 16.8 per cent), administrative and support services ( down 14 per cent), accommodation and food (down 13.2 per cent), arts and recreation ( down 8.2 per cent) and other services (down 7.2 per cent). That reflects both voluntary behavioural changes in response to the pandemic, the impact of government containment measures (including border closures, travel restrictions and limits on capacity at venues) and the effect of bushfires at the start of last year.

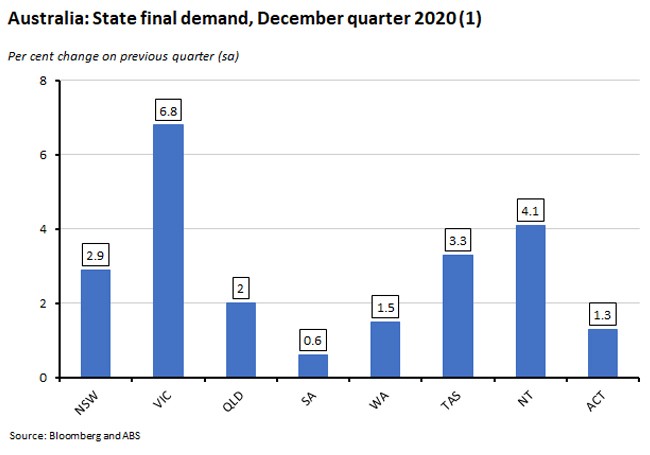

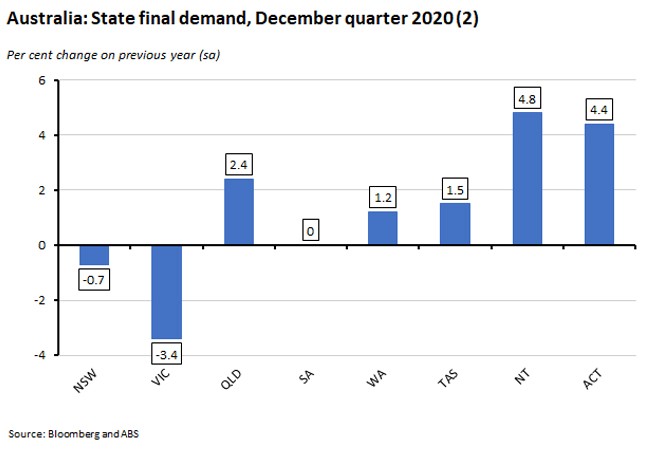

By state and territory, state final demand expanded at a rapid 6.8 per cent (seasonally adjusted) over the quarter in Victoria, as that state emerged from lockdown. There were also strong growth results for the NT (up 4.1 per cent), Tasmania (up 3.3 per cent) and New South Wales (up 2.9 per cent).

Compared with the December quarter of 2019, however, state final demand was still down over the year in Victoria and New South Wales, and flat in South Australia.

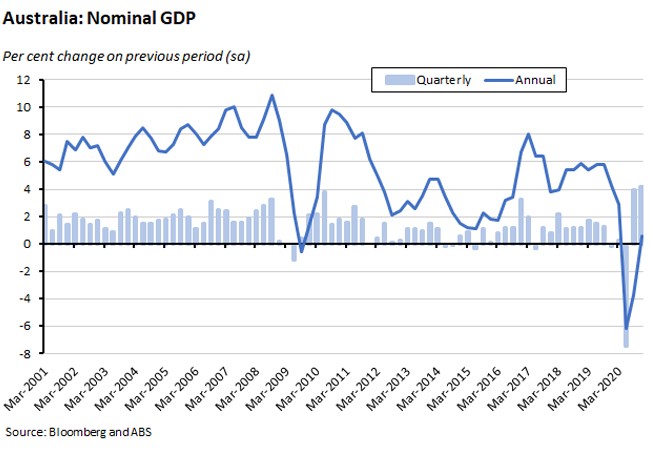

Finally, turning from real (volume) measures of GDP to nominal measures (which include the impact of price changes), nominal GDP rose by 4.2 per cent over the quarter in Q4:2020 in its fastest increase since Q3:1983. That in turn saw nominal output up 0.6 per cent relative to the December quarter of 2019.

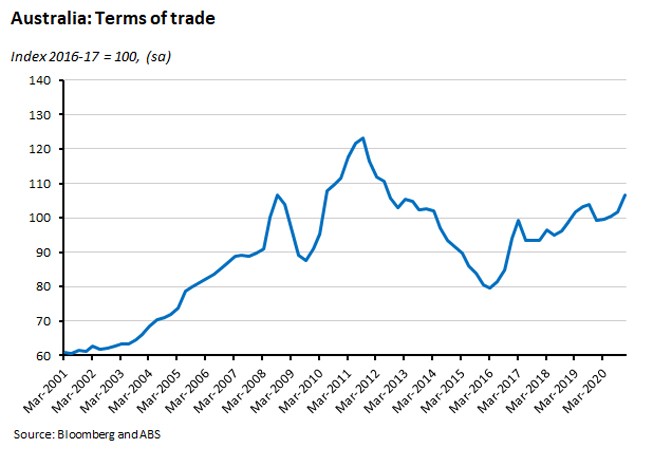

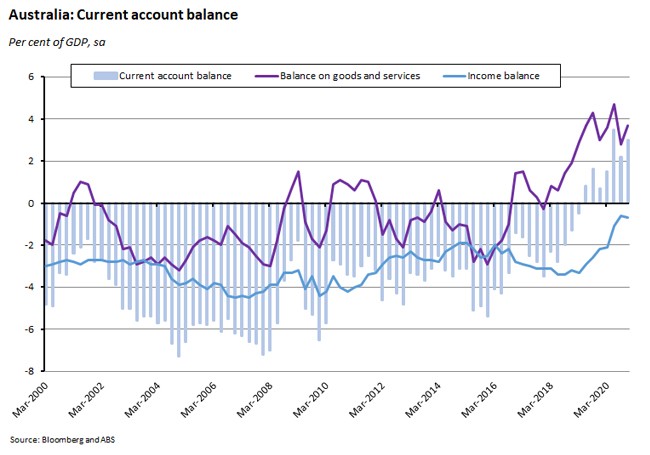

The strength in nominal GDP reflected a 4.7 per cent quarterly rise in the terms of trade, driven by higher export prices and in particular the high level of iron ore prices discussed last week. By the end of last year, Australia’s terms of trade were more than seven per cent higher than in the corresponding quarter in 2019.

Why it matters:

The December GDP result surprised to the upside: the consensus forecast had been for a 2.5 per cent quarterly increase which would have left real output down 1.9 per cent down over the year. Instead, real output at the end of the final quarter of last year was just 1.1 per cent below its level in Q4:2019.

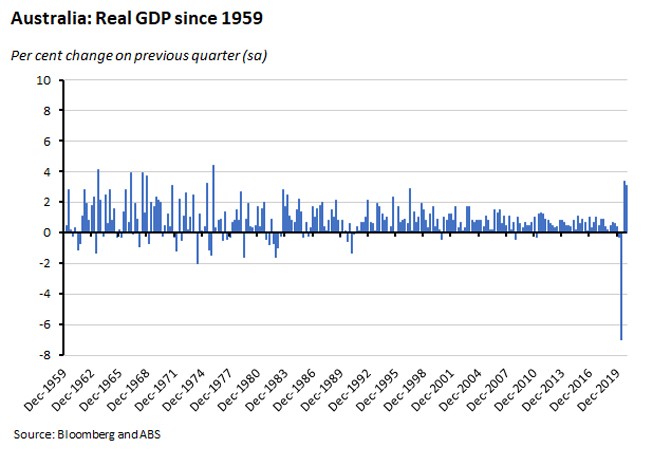

According to the ABS, this was the first time in the history of Australia’s National Accounts that real GDP has grown by more than three per cent per cent in two consecutive quarters.

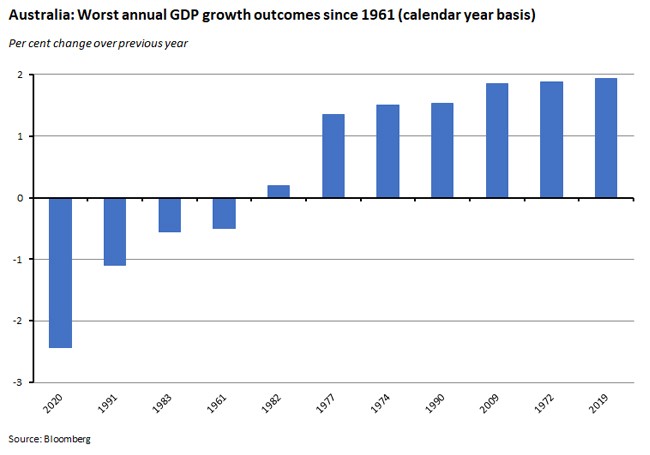

Across 2020 as a whole, real GDP shrank by 2.4 per cent. That is by far the worst annual decline in output in decades - much larger than the downturns seen in 1983 and 1991, for example.

Even so, the decline in output is much less than had been feared at the peak of the pandemic (back at the time of the May 2020 Statement on Monetary Policy, for example, the RBA thought that GDP might fall by five per cent in 2020 and in the same month the median consensus forecast reported by Bloomberg was for a 4.7 per cent drop in activity.) It also leaves Australia looking pretty good by the standard of other advanced economies, most of which have suffered significantly larger output losses, with declines ranging from 3.5 per cent in the United States, 4.8 per cent in Japan, 6.4 per cent across the EU (including falls of more than eight per cent in France and Italy and an 11 per cent crash in Spain) to a near-ten per cent slump in the UK.

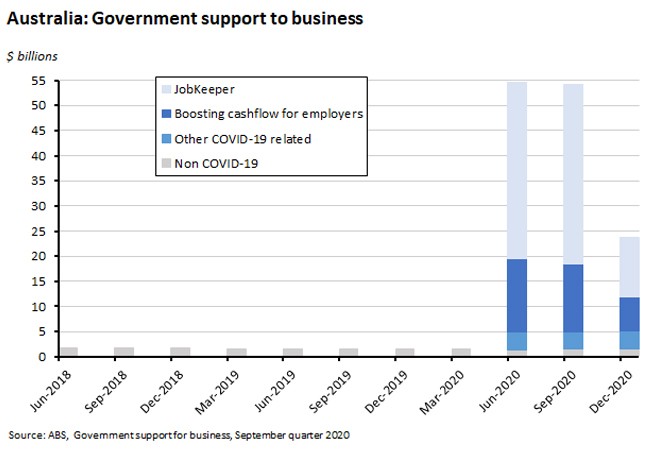

Good health outcomes and a large and effective dose of policy support have powered the recovery, which to date has been overwhelmingly household-led. As noted above, 2.3 percentage points of the 3.1 per cent quarterly growth increase in Q4 came from household consumption, and a further 0.4 percentage points came from the housing market, split between dwelling activity and ownership transfer costs. Government policy has clearly played an important role here, providing significant support to household incomes (JobSeeker supplement), sustaining employment (JobKeeper), boosting housing market activity (Homebuilder) and encouraging business investment (the instant asset write-off). Encouragingly, then, the strong Q4 result came despite a significant winding down in some of those support measures:

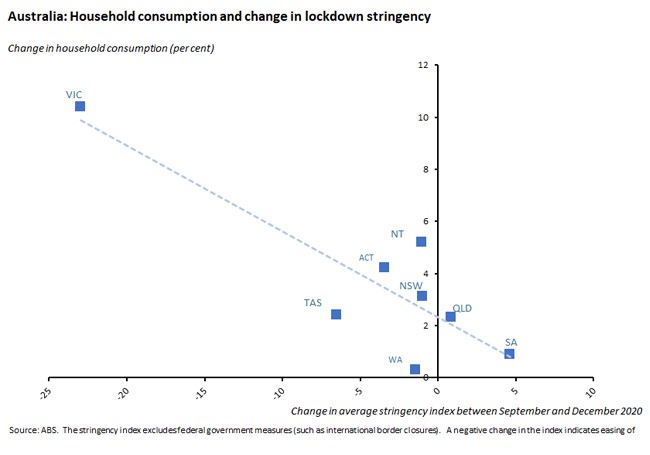

The easing of state-level restrictions has also played an important role in the pattern of economic growth, with the ABS pointing to the impact on household demand in particular, with Victoria seeing household spending rise 10.4 per cent over the quarter as lockdown restrictions were lifted, compared to a 2.3 per cent increase across the rest of Australia. Even so, the level of spending in Victoria remains 7.2 per cent below its pre-COVID level.

One final point: a look at changes in the pattern of consumer spending across the year shows some quite dramatic substitutions in spending, with a collapse in purchases of transport services and expenditure on cafes and restaurants on the one hand, and a pick up in spending on vehicles, alcoholic beverages and household furnishings and equipment on the other.

What happened:

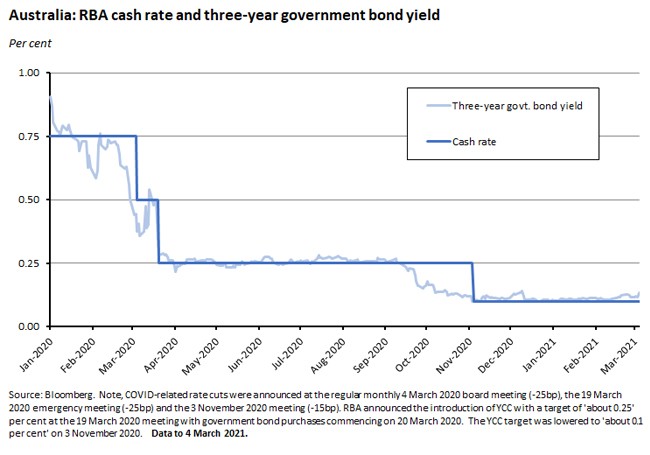

At its meeting on 2 March the RBA decided to leave all its major policy settings unchanged: the targets of 10 basis points for the cash rate and the yield on the 3-year Australian Government bond, as well as the current parameters of the Term Funding Facility (TFF) and the government bond purchase program were all untouched.

The accompanying statement stressed that the RBA ‘remains committed to the three-year yield target and recently purchased bonds to support the target and will continue to do so as necessary… bond purchases under the bond purchase program were brought forward this week to assist with the smooth functioning of the market. The Bank is prepared to make further adjustments to its purchases in response to market conditions.’

And the statement concluded by noting that:

‘The Board remains committed to maintaining highly supportive monetary conditions until its goals are achieved. The Board will not increase the cash rate until actual inflation is sustainably within the 2 to 3 per cent target range. For this to occur, wages growth will have to be materially higher than it is currently. This will require significant gains in employment and a return to a tight labour market. The Board does not expect these conditions to be met until 2024 at the earliest.’

We also received a short update on the status of the asset purchase program, with the statement informing us that a cumulative $74 billion of Australian government and state government bonds has been purchased to date under the initial $100 billion program, with a further $100 billion to come. Moreover, ‘the Bank is prepared to do more if that is necessary.’

Why it matters:

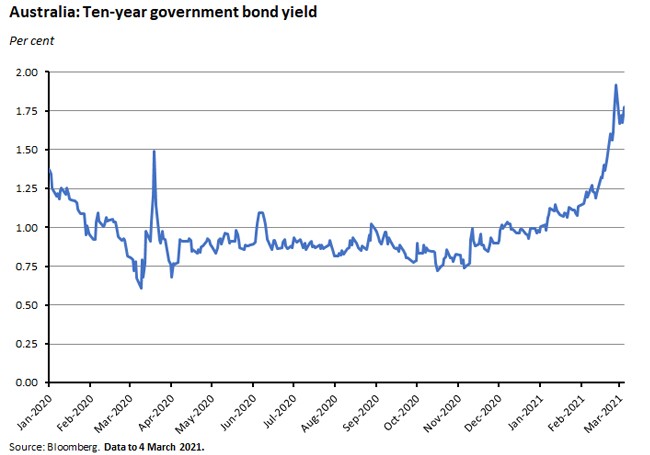

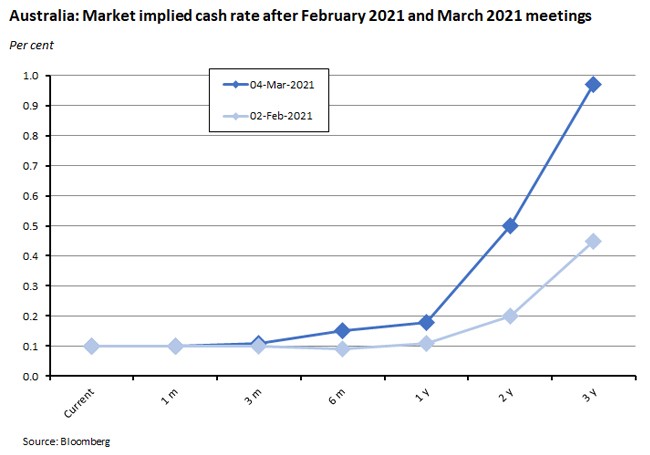

The run-up to this week’s meeting made for a rather mixed backdrop. On the one hand – and as discussed in detail last month – the first week of February had brought a comprehensive download on the RBA’s thinking in terms of monetary policy settings and economic forecasts. All of which had made it very clear that no policy change was imminent with the central bank expecting a slow journey back to its inflation target. On the other hand – and as discussed last week – the global reflation trade plus Australia-specific optimism had placed both bond yields and the dollar under strong upward pressure, challenging the RBA’s commitment to keeping borrowing costs low in general and its yield curve control target (YCC) in particular.

Those developments had called forth a big step up in bond purchases under the YCC program, with the RBA buying $1 billion of bonds last Monday in its first YCC operations in about two months, followed by $3 billion of purchases last Thursday and another $3 billion on Friday to drive the three-year yield back down towards 0.1 per cent. At the same time, the RBA also ramped up the pace of purchases under its QE program, which is focused on the longer end of the yield curve: on Monday this week, it doubled the size of its bond buying from the typical $2 billion to $4 billion.

Against this backdrop, the RBA used the statement accompanying this week’s meeting to indicate that it was holding to its line on monetary policy. Sharp-eyed readers will have noted that the concluding statement this month lined up word-for-word with the previous statement (except for a pre-amble in the February version), including the view that Martin Place does not anticipate changing the cash rate until 2024 ‘at the earliest.’ The RBA also signalled that it stands ready to use its existing program of asset purchases to maintain its cap on borrowing costs.

The reiteration of last month’s message is not a surprise. While the run of data over recent weeks has certainly been positive, there hasn’t been enough to justify a major shift in a forecast that is only a month old. Still, it’s also clear that markets are increasingly optimistic about the outlook, and that in turn is impacting their view on the likely trajectory of interest rates, especially more than one year out.

What happened:

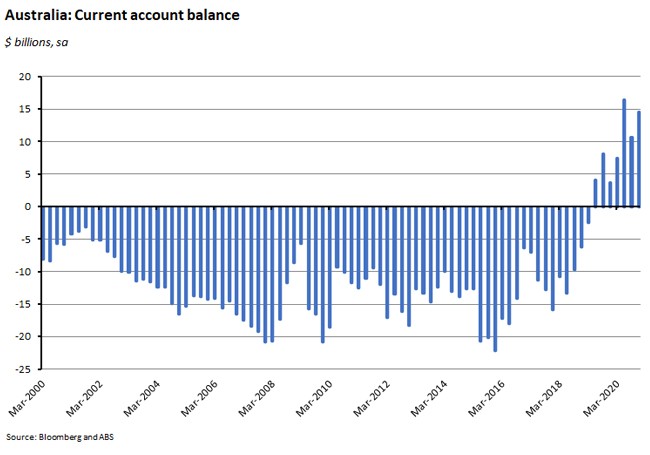

According to the ABS, Australia’s current account surplus in Q4:2020 rose by $3.8 billion to $14.5 billion (seasonally adjusted).

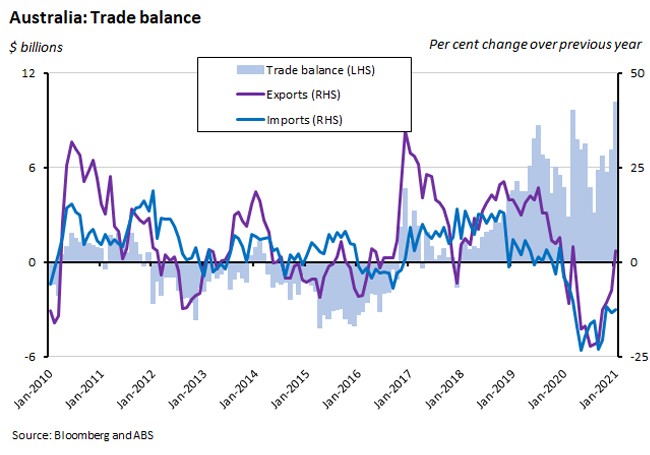

The surplus on the goods and services trade balance rose from $13.7 billion in Q3:2020 to $18.1 billion in Q4:2020 while the net primary income deficit widened from $2.7 billion to $3.2 billion. The trade surplus reflected an eight per cent increase in exports of goods and services vs a four per cent rise in the value of imports.

Expressed as a share of output, the current account surplus ended last year at three per cent of GDP.

Why it matters:

The December quarter result marked Australia's seventh consecutive quarterly current account surplus. It was the product of another large trade surplus with the ABS pointing to strong exports of metal ores (up $3.7 billion) and cereal grains (up $1.3 billion). The value of imports also picked up in the December quarter, driven by increased demand for consumption goods and some sign of the instant asset write-off policy leading to increased demand for some capital goods such as industrial transport equipment and machinery equipment (see also the discussion on investment in the previous story).

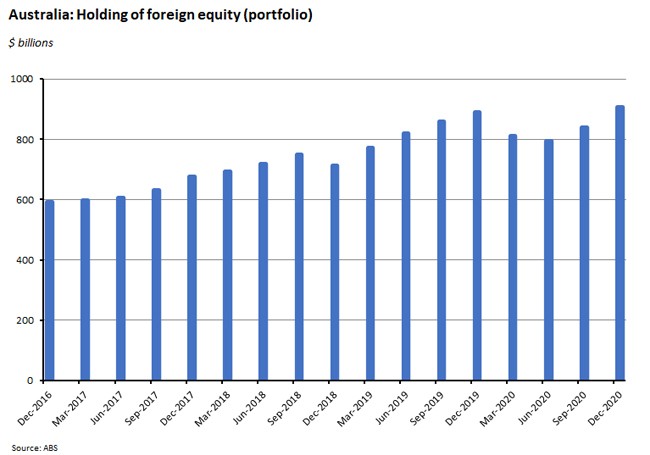

One other point of interest highlighted by the Bureau: After seeing Australia’s holdings of foreign equities fall in the March and June quarters of last year as superannuation funds sold off shares to provide liquidity for the COVID-19 Early release of superannuation program, holdings have risen again in the September and December quarters.

The ABS also reported that the December quarter of last year saw strong foreign investment in Australian government securities.

What happened:

The ABS said that Australia’s goods and services trade surplus increased by $3.0 billion to $10.1 billion in January this year (seasonally adjusted). Exports of goods and services rose six per cent over the month and 2.9 per cent over the year while imports of goods and services fell two per cent over the month to be down more than 12 per cent in annual terms.

Why it matters:

January marked a new dollar record for Australia’s monthly trade surplus, beating the previous record $9.6 billion surplus achieved in March 2020. High iron ore prices (discussed last week) are an important part of this story.

What happened:

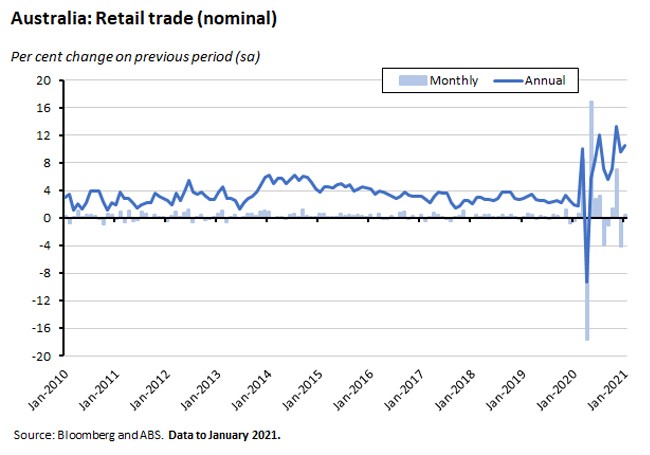

The ABS reported that retail turnover rose 0.5 per cent month-on-month (seasonally adjusted) in January this year to be 10.6 per cent higher than in January 2020.

Why it matters:

The preliminary estimate for turnover had been for a 0.6 per cent rise, so the final numbers were largely consistent with that early read. Double digit growth in annual terms – despite January including the end of the Sydney Northern Beaches lockdown plus a three-day lockdown in Brisbane that dragged down Queensland’s numbers – suggests that the robust recovery in consumer spending that was a big feature of the Q4 GDP results discussed in detail above has been sustained into the opening month of 2021.

What happened:

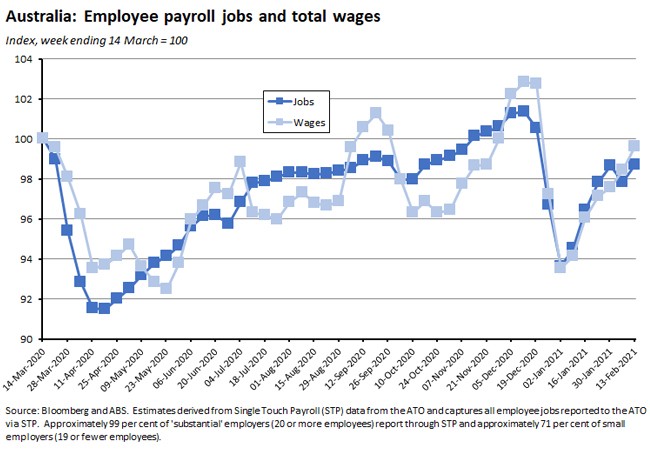

Between the weeks ending 14 March 2020 (the week of Australia’s 100th COVID-19 case) and 13 February 2021, the number of payroll jobs fell 1.3 per cent while total wages paid declined 0.4 per cent. The ABS said that over the most recent two weeks of data, between the weeks ending 30 January 2021 and 13 February 2021, payroll jobs were unchanged while total wages paid rose 2.1 per cent.

Victoria and Western Australia were the only states to see payroll jobs decline over the most recent fortnight of data (both down 0.4 per cent), with the WA result likely influenced by lockdown restrictions that applied in the first week of February.

Why it matters:

While the number of payroll jobs was flat over the past fortnight, that meant that job totals by mid-February were 0.5 per cent lower than in the same period last year, and a bit more than one per cent below their pre-pandemic level.

What happened:

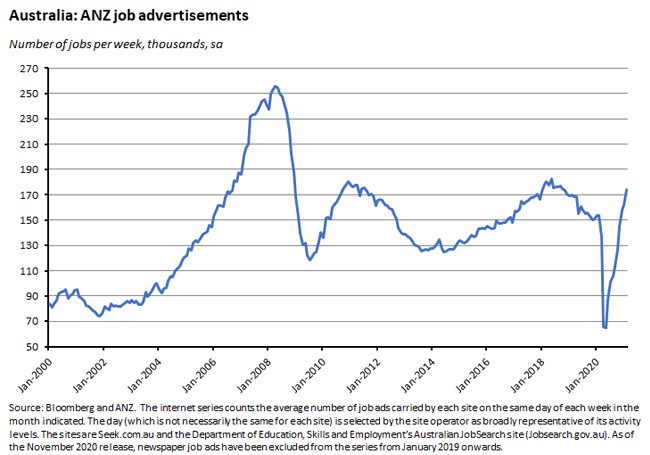

ANZ Australian job ads rose (pdf) 7.2 per cent month-on-month in February this year to be 13.4 per cent higher than in February 2020.

Why it matters:

According to ANZ, job ads are now at their highest level since October 2018, with that 13.4 per cent rise above pre-pandemic levels equating to an additional 20,500 jobs on average being advertised each month. That should be positive news for the future rate of recovery in the labour market, especially keeping in mind that labour market resilience is soon to be tested by the end of the JobKeeper program.

What happened:

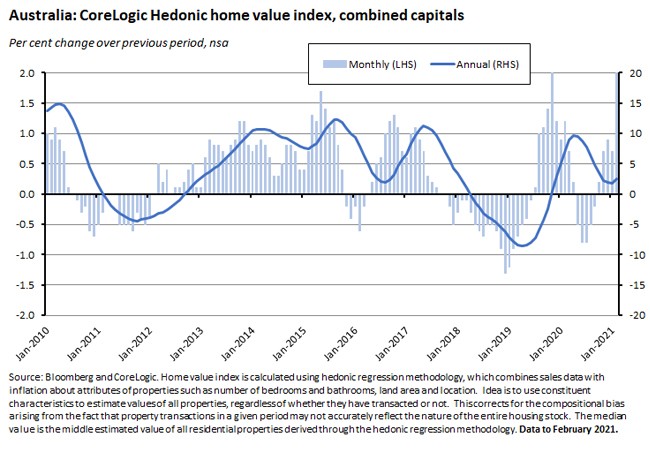

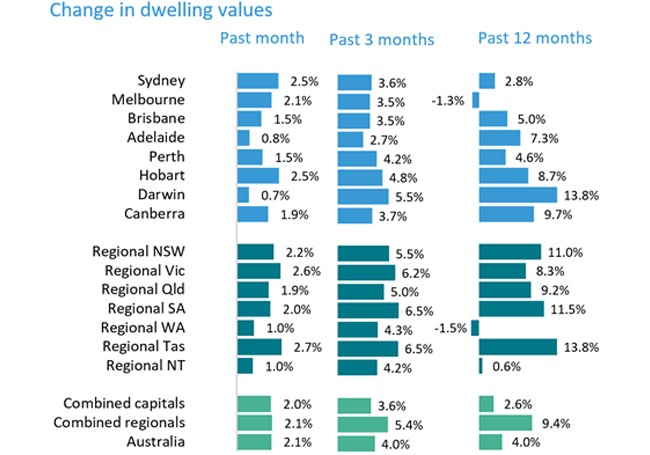

CoreLogic said that Australian home values rose 2.1 per cent over the month in February to be four per cent higher in annual terms. Dwelling values in the capital cities were up two per cent over the month and 2.6 per cent over the year.

The combined regionals value index was up 2.1 per cent over the month and 9.4 per cent higher than the February 2020 value.

Last month brought strong increases in Sydney and Hobart (both up 2.5 per cent over the month) and in Melbourne (up 2.1 per cent) along with monthly price increases of two per cent or more in regional Victoria, regional Tasmania, regional New South Wales, and regional South Australia.

Why it matters:

February’s results show activity across Australia’s housing markets continuing to gain momentum. Last month’s 2.1 per cent gain in the national index was the largest monthly increase since August 2003, while CoreLogic said the pattern of rising values across each of the capital city and rest of state regions demonstrated a synchronised growth pattern that hasn’t been seen since mid-2009 through to early 2010, back when post-GFC stimulus supercharged demand.

What happened:

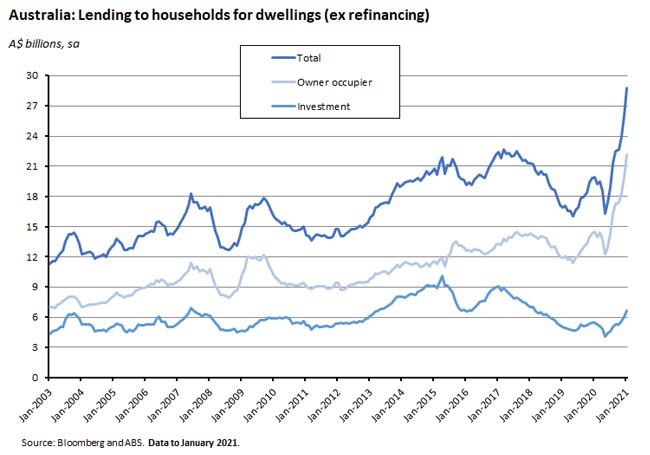

The ABS said that new loan commitments for housing rose 10.5 per cent over the month (seasonally adjusted) in January 2021, leaving them up a hefty 44.3 per cent over January 2020.

The value of new loan commitments to owner occupiers rose 10.9 per cent over the month and 52.3 per cent over the year, while loans to investors were up 9.4 per cent month-on-month and 22.7 per cent year-on-year.

Why it matters:

Lending for housing hit a new record high in January this year – consistent with the booming housing market story being told by the price data discussed earlier.

The ABS highlighted the impact of the introduction of the government’s HomeBuilder grant in June 2020 in contributing to record rises in the value of construction loan commitments. The Bureau also pointed to the fact that January saw the number of owner occupier first home buyer loan commitments climb 9.6 per cent, taking them back to their highest level since May 2009, a period when similarly rapid growth was spurred by the temporary tripling of the first home owner grant in response to the GFC.

What happened:

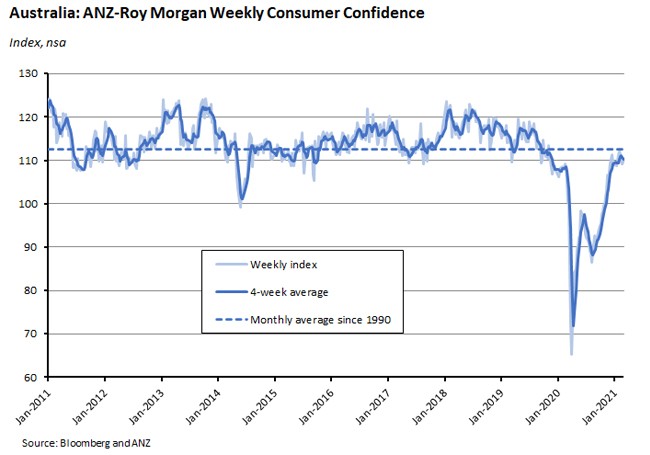

The ANZ-Roy Morgan weekly consumer confidence index rose one per cent to an index level of 110.3 for the weekend of 27-28 February 2021.

Why it matters:

After three consecutive weeks of (small) declines in confidence, the start of Australia’s vaccine program saw a bounce in consumer sentiment that has taken confidence levels to 5.5 index points above where they were in the same week of last year.

What I’ve been reading . . .

- Two additional releases from the ABS that didn’t make it into the previous list due to that section’s already excessive length. First, the Bureau reported that the number of total dwellings approved fell 19.4 per cent (seasonally adjusted) in January, with approvals for private sector houses down 12.2 per cent and apartments down 39.5 per cent. The marked decline in approvals for private house follows the same series hitting an all-time high in December 2020 and despite January’s fall, approvals remain 38 per cent higher than in January last year. At the same time, approvals for private sector dwellings excluding houses (that is, for townhouses and apartments) dropped to their lowest level since January 2012. Second, here is the February 2021 release of the ABS Business Conditions and Sentiments survey (which is the renamed Business Indicators, Business Impacts of COVID-19 survey). By last month, 30 per cent of businesses told the ABS that they were impacted by reduced cash flow and 28 per cent by reduced demand, down from 72 per cent and 69 per cent respectively in April 2020. And 41 per cent of businesses reported being impacted by COVID-19 restrictions in February this year, down from 53 per cent in April last year.

- Also from the ABS, a look at online retail sales and the impact of the pandemic.

- Jacob Greber and Hans van Leeuwen in the AFR worry that Australia may have to pay a price for not being a member of the ‘climate club’ as the prospect of a carbon border adjustment mechanism becomes increasingly likely.

- The latest quarterly statement by Australia’s Council of Financial Regulators covers developments in the housing market and – despite the surge in prices and new lending noted above – takes a generally sanguine view, noting that: ‘Housing credit has picked up a little and is growing at a moderate pace. Commitments for new owner-occupier housing loans have increased strongly in recent months, consistent with most other indicators of housing market activity. There has been some increased availability of mortgage finance recently, though lending standards are generally being maintained at this stage. The Council places a high emphasis on lending standards remaining sound, particularly in an environment of rising housing prices and low interest rates. It will continue to closely monitor developments and consider possible responses should lending standards deteriorate and financial risks increase.’

- The RBA’s March chart pack is now available.

- Peter Martin argues that Treasurer Josh Frydenberg has the opportunity to be a ‘transformational’ treasurer when it comes to driving down the rate of unemployment.

- The Grattan Institute on the future of Aged Care after the release of the Royal Commission report.

- John Ravenhill worries that UK accession to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) may have some downsides for Australian interests.

- In the WSJ, Greg Ip asks whether an outbreak of inflation in the United States is a risk. Not for now, he concludes, given that the usual conditions (tight labour market, rising public inflationary expectations) are ‘glaringly absent’. In the longer term, however, changing political priorities and shifting monetary policy regimes might be a cause for concern.

- Related, the Economist argues that inflation fears will persist, and that as a result we should expect more bond market jitters of the kind we saw last week.

- See also Ken Rogoff in the AFR on whether a reversal of globalisation is an important new source of inflation risk.

- Sticking with the theme: the contest between the Friedman (monetary aggregates) and the Phillips (curve) models of inflation.

- This blog post from the IMF weighs the evidence on negative interest rates as a policy tool and, contra the RBA’s scepticism, finds that they have worked, easing financial conditions (and, in the process, likely supporting growth and inflation) without adding significantly to financial stability concerns. The article concedes that negative rate policies remain politically controversial but says that this is partly because they are often misunderstood.

- More from the IMF: The Spring 2021 edition of its Finance & Development magazine is now online. I haven’t had the time to dig into this yet, but the lead essay by Daron Acemoglu on Remaking the Post-Covid World, which talks about a new approach to automation, looks like an interesting place to start.

- Freedom House’s Freedom in the World 2021 report is badged as Democracy under Siege. According to the report, the ‘long democratic recession is deepening’ as it records a 15th consecutive year of decline in global freedom, with the number of countries experiencing deterioration exceeding those with improvements by the largest margin recorded since the negative trend began in 2006. (Australia retains its score of 97/100 and its status as ‘Free’.)

- The FT’s Martin Wolf casts his eye over the debate on central bank policy frameworks (Target inflation? Or target debt and/or asset prices?) and comes down in favour of current settings, although he doesn’t spend much time on either price-level or nominal GDP targeting, which are arguably the most credible alternative frameworks currently being proposed.

- FT Alphaville takes Citi to task over its latest report (big pdf) on bitcoin. And then does it again for chart-crimes.

- Five thirty eight on how bad math and dodgy analytics ruined English football.

- Nouriel Roubini does his thing (that is, finding reasons to worry about big, bad things happening).

- And two long form readings this week. As preparation for this week’s AGS session with Professor Rebecca Henderson, I recently finished reading her book Reimagining Capitalism: How Business Can Save the World. It’s organised around the idea of ‘why and how we can build a profitable, equitable and sustainable capitalism by changing how we think about the purpose of firms, their role in society, and their relationship to government and the state.’ Henderson begins by identifying three critical problems – massive environmental degradation, economic inequality, and institutional collapse – and then offers a critique of the traditional argument that business should just focus on maximising shareholder value. This makes for a poor guide, she argues, in a world where we don’t price externalities properly, where people lack the necessary skills to be able to benefit from genuine freedom of opportunity, and where firms are increasingly able to skew the ‘rules of the game’ in their own favour. If markets are neither free nor fair, Henderson writes, we have a problem. Her proposed solution includes five major propositions: (1) creating ‘shared value’, whereby firms aim not just to make a profit, but also to ‘build prosperity and freedom in the context of a sustainable planet and a healthy society’; (2) building ‘purpose-driven’ organisations, with so-called ‘high road’ firms treating their employees with dignity and respect; (3) Rewiring finance to encourage investors to take a long-term view that will enable firms to adopt those priorities of creating shared value and taking the high road; (4) building cooperation across businesses (in the form of self-regulation) and (5) rebuilding institutions, including governments. It’s a good read and I really enjoyed the chance to discuss some of these ideas with her during this week’s AGS – she makes for a very good advocate of her position. One of the questions I raised is that our current version of capitalism appears to have delivered what can sometimes look like a peculiar assignment of responsibilities: we appear to be tasking governments and central banks with delivering growth (via stimulus and QE) while asking businesses to manage inequality, deliver environmental sustainability and protect minority rights. Professor Henderson had a nice answer to that question as well as several others, and if you missed the original session at the AGS, hopefully you can catch a recording. Finally, I thought that the book make a nice contrast with one I read a couple of years’ ago and (I think) mentioned in one of the early Weekly reading roundups – Anand Giridharadas’s Winners take all, which is much more pessimistic about the potential contribution that business and other winners in the current set up can make in some of these areas.

- I also finished a second book this week, although this time in audiobook form. Anne Applebaum’s Twilight of Democracy offers an interesting take from the centre-right on the rise of populism, by offering a personal and personality-driven perspective on recent political developments in Poland, Hungary, Spain, the UK and the United States. Intentionally, there’s relatively little in the way of grand theories here, although Appelbaum does reference some of the usual suspects along with references to the role played by the presence of an ‘authoritarian tendency’. Instead, much of the focus is on individuals and individual motivations which makes for an easy read (or in my case, listen) but not always a completely satisfying one.

- Finally, your mileage may well vary on this one, but a friend recently directed me to Adam Curtis’s latest documentary series for the BBC, Can’t get you out of my head. You should be able to find the episodes on YouTube here. Reviews from The Economist (‘ambitious but largely forgettable’) here and somewhat more friendly from the FT (‘the notion of “Time and Propinquity” rather than logic and causality as a tool to scrape off the official story to reveal underlying patterns’) here may give you a flavour. If you’re not already familiar with Curtis’s work, which adopts a quite distinctive style, maybe dip into the first episode and see if it might be your thing. Actually, I’m still not completely sure what to make of this one myself, which on reflection also makes for a rather strange recommendation! Still, I did find it interesting – and visually stimulating – enough to watch every episode.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content