Skilled management will boost your capacity to survive long industry life cycles, writes Phil Ruthven FAICD.

Life is full of risks. It starts with the circumstances of our birth, which century or country we end up in and the degree to which we suffer good or bad fortune, take charge of our lives or depend on serendipity.

Business is risky, too. There are 2.2 million businesses in Australia today — down more than 260,000 from 2016, according to data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Fortunately, not many of them cease via insolvency (1.4 per cent) or bankruptcy (0.5 per cent of unincorporated businesses). However, 310,435 new businesses were created, so entrepreneurship and some amount of risk-taking appear alive and well.

Bankers and insolvency experts know that when it comes to risk, generally two-thirds is internal (organisational). The remaining third of the risk is external — which has to do with the industry that the business is in and the pressures on it. Let’s look at these risk factors in more detail.

Industry risk

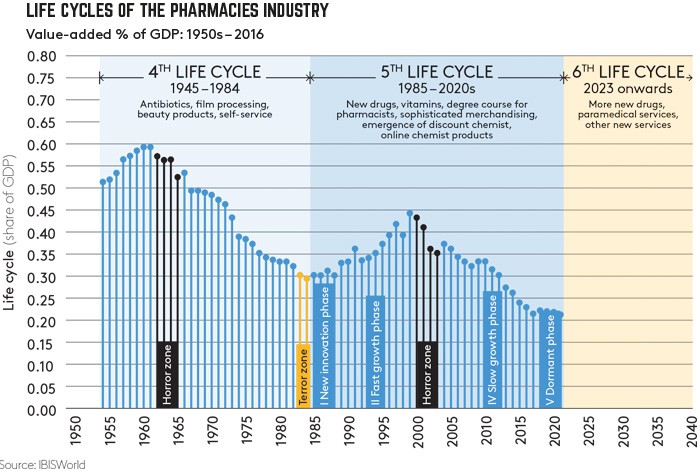

It’s often said that there is no such thing as a bad industry; only bad businesses and their management. While there’s some truth to this saying, it doesn’t apply all of the time. IBISWorld has analysed the life cycles of more than 270 of the nation’s industry categories over the past 45 years. Virtually all of Australia’s 509 industry categories run in long cycles of about 43 years (plus or minus five years), with some less, and a handful much longer.

Any new industry life cycle runs through seven phases, from innovation and fast growth to maturation, followed by rationalisation, slow growth, dormancy and further rationalisation (see table above right). Each of these phases demands different strategies, management and risk minimisation. These are driven by five-way changes — through products, customer/market mix, geography, systems and technology, and ownership.

It takes until the top of the new cycle for 60 per cent of the industry’s revenue to reflect these changes, and the end of the life cycle for 80 per cent to reflect the new changes. It’s a slow process.

The riskiest stages are the rationalisation periods — the “horror zone” (four years) and terror zone (two years).

Nearly all Australian industries experience these six years of rationalisation and disruption involving unforeseen (but often predictable) market shocks and irrational competitor behaviour. This means there are times when an industry might rightly, albeit temporarily, be called a “bad” industry to be in — but not if your business happens to be one that emerges as a winner.

There are once-in-a-lifetime opportunities to be seized in these moments (examples include the rationalisation of the cardboard packaging sector to Visy Board and Amcor when the Smorgon family capitulated in the late 1980s and the wine industry rationalisation in the early 2000s).

People assume these life cycles must be getting shorter due to technology, but they’re not. While they don’t change, many product life cycles are getting shorter within industries.

No industry escapes these life cycles, the five-way changes with each new cycle or the rationalisation that results. Our research shows that no industry is exempt.

Most industries have relatively low year-to-year volatility, as illustrated in the life cycles of the pharmacies industry (see chart at right).

This is a big industry with revenues of more than $16 billion and an average 40-year cycle — measured as the industry’s value-added share of GDP (economic importance) — as seen in the chart.

This industry is now completing its fifth life cycle since 1822 and will enter a very different sixth life cycle early in the next decade.

The universities sector is another example. It is coming to the end of its fourth life cycle since the early 1850s and will endure some severe pressures over the next four to five years. It will begin its fifth life cycle with spectacular five-way changes to the sector in the early 2020s.

Our wine industry differs in that it runs in long eras of around 50 years with two life cycles inside these eras, each complete with its own horror and terror rationalisation zones. A number of industries experience extreme volatility — general insurance is one of these. Insurance has a lot of variables, including natural disasters — perhaps exacerbated by climate change — as well as man-made calamities such as terrorism. This industry, which has a long life cycle of 50 to 55 years, has entered its fourth life cycle in Australia.

A strong, if not bulletproof, balance sheet is a condition of survival in this industry, as is spreading risk via underwriting options. Climate change risks in insurance include more wave and hurricane activity.

For all of this diversity, the vast majority of the nation’s 509 categories of industry are in the medium and medium-to-high risk categories, with only a handful each in the high or very low risk categories.

Strategic risks of management

If we focus only on the industry risks, we might overlook an important fact — that management skill is the factor that matters most when it comes to risk. There is a much wider spectrum of good and bad management than there are so-called good and bad industries; that is, we tend to be weak on management bench strength in Australia.

The Australian Securities and Investments Commission, which analyses companies that become insolvent, has developed an extensive list of the impending signs of insolvency. This red-flag list includes: ongoing losses, poor cash flow, absence of a business plan, disorganised internal financial accounts, inadequate cash-flow forecasting and budgeting, growing debt, overdue liabilities (including tax and super), board dysfunctionality and a rising number of complaints from suppliers. They’re all blatantly obvious with hindsight — and predictable for a well-managed business.

What are the key strategic risks when it comes to management? Excess diversification or an unsafe position in the industry (neither major nor niche), a lack of unique intellectual property, minimal innovation and R&D, dangerous levels of debt to equity or too many hard assets on the balance sheet (lead in the saddlebag), the wrong CEO, an inadequate board and poor organisational culture come to mind.

Few companies ever make all of these mistakes, but making enough of them explains why the average profitability of the top 2000 is a very ordinary 8.7 per cent over the past five years. One in three do better than the average.

The nation’s top 2000 businesses account for more than 45 per cent of Australia’s $5 trillion in revenue. One in eight of these businesses earn more than 20 per cent net profit after tax on equity over any five-year period — that is world’s best practice. That window eliminates serendipity, which means those CEOs and boards earned their achievements. Almost all of Australia’s industry divisions housing the 509 classes of industry are represented in this world-class performance, so there are no bad industries. But a greater percentage of the top 2000 businesses run losses over the same period.

Good management can overcome any industry challenges. How Fortescue Metals Group handled the iron-ore price crash is a case in point. Australia has some truly great companies, CEOs, management and boards. Let’s see if we can substantially increase that proportion over the next decade or so.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content