Following the landmark 2015 Paris Agreement and new research into the world’s largest investors and climate related risk, John Connor, CEO of The Climate Institute explores challenges and long-term liability risks facing directors.

Earlier this year at the Australian Institute of Company Directors’ Australian Governance Summit, David Gonski told an audience of 1000 of Australia’s senior business leaders that board directors should take a more long-term perspective on their roles. So, how and why does climate change factor in that advice? And is action already under way?

Prior to the Paris Climate Summit last December, Mark Carney, the Governor of the Bank of England, described his concept of the “Tragedy of the Horizon” - the threats that climate change poses to long-term shareholder value and, potentially, financial stability beyond the traditional horizons of the business and political cycles.

Carney outlined the physical risks already impacting property, agricultural and tourism asset classes through the increased frequency and greater intensity of storms, drought and bushfires as well as, for example, the bleaching of the Great Barrier Reef.

Then he talked about transitional risks - changes in policy, technology and physical risks that could prompt a potentially sudden reassessment - a “jump to distress” - of the value of a large range of assets.

Looking into long-term liability

Carney also described liability risks, particularly referring to carbon extractors or emitters, referring to the impacts that could arise up to decades in the future where parties who have suffered loss and damage from the (ignored) effects of climate change seek compensation from those they hold responsible. One example of such litigation is under way in some US states, where it is being investigated whether Exxon misled investors about its knowledge of climate science.

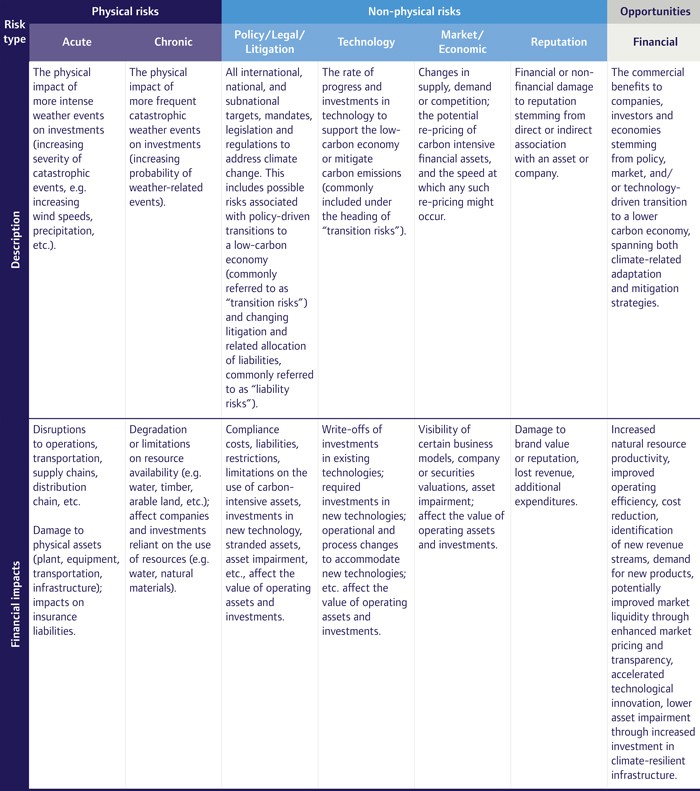

At the Paris Summit, the G20’s Financial Stability Board launched a Taskforce on Climate Related Financial Disclosures. It has just released a Phase One Report providing an even more detailed typology of physical and non-physical risks and opportunities. Last year, The Climate Institute also examined the issues of Australia’s Financial System and Climate Risk.

The Paris agreement was particularly significant because it set goals to keep global warming “well below” 2°C above pre-industrial levels and to “pursue efforts” to keep warming to 1.5 degrees. With warming already around one degree above, there is mounting urgency. This highlights the importance of the now mainstream understanding that to achieve any of these goals requires economies to sit at net zero emissions or below.

The world’s largest institutional investors, like superannuation funds and sovereign wealth funds, are already moving on climate risks. The Asset Owners Disclosure Project’s fourth Global Climate 500 Index, released earlier this month, showed around half are now taking action either through assessing portfolio risks, making low-carbon investments or through more direct engagement with corporate governance. In 2016, there has been a 62 per cent jump in support of shareholder resolutions focused on climate change, with 60 investors (12 per cent) surveyed voting in favour of at least one (up from just 7 per cent in 2015).

One way companies are integrating long-term perspectives on climate is by stress testing their business models to see if they can cope in economies avoiding two degrees warming. BHP has already done it. Westpac, AGL and Origin are doing so. This will be an increasingly important approach.

Australia has had a turbulent ten years in climate and clean energy politics; this should provide directors with more, not less, reason to take both long and near-term perspectives on climate change. There is a widening gulf between community, investor and policy-maker perspectives, which is increasing the transitional risks of sudden policy movements. The Climate Institute’s A Switch in Time report highlights the looming economic “jump to distress” if we fail to begin effective action to modernise and decarbonise our electricity system now.

The point is that the heat is not just rising on our planet, but on directors to manage climate related risks now to avert worse outcomes in the future.

Overview of common climate-related risks and opportunities

For more information visit: Phase 1 Report of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures

Click here for more information about the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures and the Phase One submission process.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content