Australian corporate tax is on the way down. Stephen Walters GAICD asks, will it be in time to maximise potential benefits — and will those benefits ever really “trickle down”?

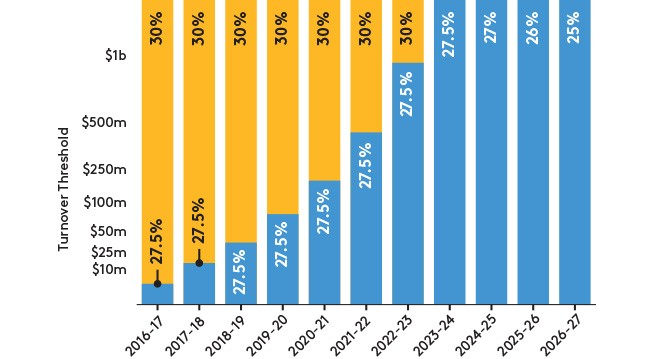

The good news is that the government is committed to cutting Australia’s corporate tax rate, among the highest in the world. Modest tax cuts for many smaller businesses are already legislated and in place.

The bad news is that other countries are also reducing their corporate tax burden, but at a much faster pace. Australia is losing this global race for corporate competitiveness. The Australian government’s 10-year Enterprise Tax Plan, which the AICD supports, proposes to cut the current 30 per cent tax rate for larger companies to 25 per cent over the next decade. Smaller businesses — with an annual turnover up to $10 million — have had their tax rate lowered to 27.5 per cent so far. The next round of relief — this time for companies with an annual turnover up to $50m — is scheduled for the middle of this year.

Eventually, all companies will be paying the lower 25 per cent rate, regardless of their size.

Supporters of the plan claim that one of the reasons business investment outside mining has languished is that the corporate tax burden is too onerous. Investment has started to lift, but much of it is “reluctant” investment — the necessary replacement of ageing plant and machinery — rather than the grander, risk-taking endeavours needed to lift productivity. The government argues that lowering the tax rate will stimulate these dormant “animal spirits”.

The counter argument is that private investment in countries that already have lowered corporate tax rates has also been weak, including Canada, which has a similar dependence on resources. It follows, though, that if the after-tax return on an investment rises, thanks to lower taxes, companies should be more willing to risk their capital.

There is an ongoing debate about who tends to benefit from lowering corporate tax rates — companies and their shareholders, or the firm’s employees. The answer is both, as do taxpayers, ultimately, as company profits and employee earnings rise over time.

It is a not a zero-sum game. Research by the Commonwealth Treasury shows that the benefits of lowering the corporate tax burden are shared between shareholders and employees, with the providers of capital and labour benefiting simultaneously as the after-tax corporate profit pie grows. Treasury modelling shows the wage share benefits by more than profits.

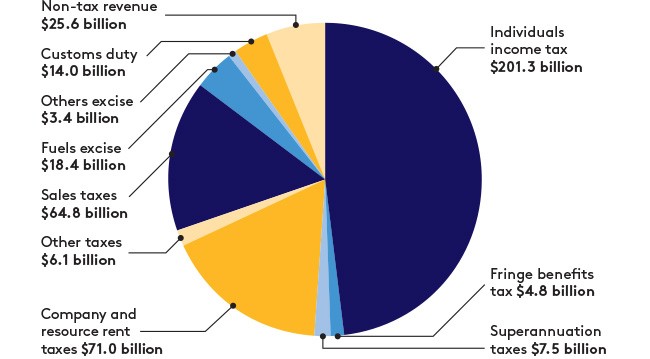

Despite this accumulated supportive evidence, legislation to enact the remainder of the government’s corporate tax plan is stalled in the parliament. Populist voices are railing against cuts for “the top end of town”. Others, including Labor and the Greens (and Hillary Clinton and The New York Times) argue that so-called “trickle-down” economics, where the benefits of corporate tax cuts flow to other parts of the economy, including employees, has failed or at very least is dubious economic theory. Some claim that the significant cost associated with lowering the tax burden cannot be borne by a Federal budget in gaping deficit now for a decade. Others prioritise spending on services that may be compromised by lowering taxes.

Cross-border comparisons of corporate tax rates are difficult, partly because of the variable generosity of allowances for deductions and interactions with other taxes. The US, for example, has a regime of cascading taxes by level of government.

Another complicating factor is Australia’s unique dividend imputation system, which works to prevent double taxation of income by firms and shareholders. Some economists argue that imputation substantially reduces the effective tax rate here, but OECD research shows the distortion is minimal.

Still, notwithstanding the perils of overseas comparisons, the message is clear. The average corporate tax rate in the OECD is 24 per cent and falling, well below our 30 per cent, which is static for larger firms. In fact, only three countries have higher corporate tax rates than Australia after the Trump administration slashed the US corporate tax rate for all companies, irrespective of size, from 35 per cent to 21 per cent, effective immediately, in January. The package included generous accelerated depreciation allowances and a lower tax burden on repatriated profits.

Theresa May’s government has lowered the UK corporate tax rate to 19 per cent, and has plans to take the headline rate down to 17 per cent by 2020. France, Norway and Japan also plan to lower their rates. Many countries in Asia already have lower corporate tax rates than our own.

At best, Australia effectively is standing still by comparison. Worse, we risk falling behind as our politicians dither. The greater peril is that increasingly mobile global investment capital could head to lower tax jurisdictions. The associated jobs and income will migrate, too. For decades, Australia has depended on foreign investors to fund our deficit of domestic savings. This now could be at risk. Prominent CEOs in Australia have become increasingly outspoken in their support for lowering the corporate tax burden, perhaps worried the government is losing the argument, despite its merits. They have committed to ensuring employee wages will grow alongside profits, following the lead of prominent business leaders in the US.

Recently, there have been calls for the government to mandate a certain proportion of the benefits of corporate tax cuts to be granted in the form of higher wages. Such interventionist fantasies, though, should be resisted. Australia already has a credible industrial relations umpire in the form of the Fair Work Commission, and an established system of advocacy. Moreover, the personal tax and benefits system is structured to equitably redistribute income.

The supportive arguments of the CEOs have not been helped by revelations that prominent companies have not paid corporate tax in Australia for some years. Write-offs against profits are legal, of course, but the accusation of aversion is unhelpful. Attention has been focused on foreign companies operating in Australia, but apparently not paying tax. This has expanded recently to include a roster of prominent Australian companies that are also paying little or no tax.

Unsurprisingly, most company directors believe the corporate tax burden should be eased. The surprise, though, is that they favour personal tax relief even more highly. This is consistent with broader opinion polling that shows patchy support for the government’s plans for corporate taxation.

One challenge for the Federal government prosecuting the case for tax relief is to convince the public that the benefits of company tax cuts are shared, particularly with employees. The government should also better highlight the risks of Australia standing still as the rest of the world moves to lower corporate tax burdens.

Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe told a parliamentary committee in Sydney on 16 February, that the global move to cut corporate tax cannot be ignored, but warned it would be a “big mistake” to pay for it with a higher deficit.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content