Phil Ruthven explains why government must rise to the challenge when it comes to taxation reform.

One wonders whether governments have serious inquiries these days. Most inquiries go nowhere, but the practice lives on with the current government via the Commission of Audit, Workplace Relations Framework (Productivity Commission), Harper Competition Policy Review and others. All headed by eminent chairpersons.

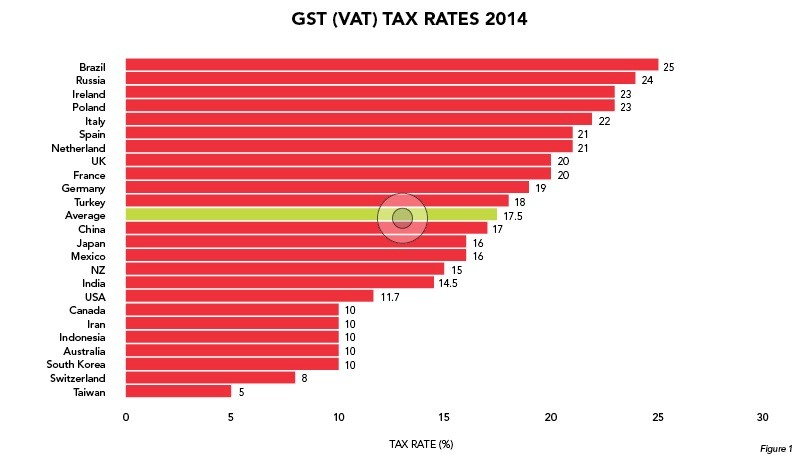

Will the taxation inquiry go anywhere? Certainly, any outcome will await the next election for endorsement, as already predicated by Prime Minister Tony Abbott and Treasurer Joe Hockey. Even before the inquiry has started, the ALP has said it will not entertain any increase in the GST despite it being one of the lowest in the developed world as shown in figure 1.

Chronic problem

Such an attitude is unbecoming of a serious intent to solve the chronic budget deficit problem besetting whoever is in power.

The current government has, up until recently and while in opposition, similarly recoiled from any intention to touch the GST. So are we seeing bloody-mindedness, ideology, politicking, or a shortage of courage in Canberra?

Our GST is nearly the lowest in the developed world, and is virtually equal lowest when the exemptions are taken into account, bringing it to the equivalent of Taiwan in figure 1.

Our neighbour New Zealand has a rate of 15 per cent and no exemptions; and the average GST across the OECD group is 17.5 per cent; more than three times our effective rate (after allowing for our exemptions).

John Key, the Prime Minister of New Zealand simply raised the country’s GST without an inquiry and without disturbing the ongoing consumer confidence (consumer sentiment index) to any extent. That is leadership; that is courage.

Our politicians should be telling businesses and the public that we have the lowest total tax rate (28 per cent of GDP) in the richest developed world economies in 2015. This will allow more room to move to lift taxes a little to balance budgets than most other countries in the OECD group and then get on with leading and running the country without that constant distraction.

Similarly, our politicans should tell the public we are running a deficit of nearly five per cent of all government expenditure and it is fixable without draconian measures. It is good housekeeping and honesty. It is fair to future generations.

Rising to the challenge

The challenge isn’t daunting. We need to lift government income across the three tiers by around two to three per cent of GDP, which would still keep Australia among the lowest taxed nations in the OECD group and be the only government at that level which is balancing its budgets. Japan and the USA, with similarly low taxation levels, are not achieving this.

Alternatively, we can cut back current benefits to pensioners, the disabled, students, health services, and other social security areas; all of which have all been built up over a long time. And perhaps tackle superannuation advantages to the rich (probably fair).

But why focus on only slashing outgoings rather than balancing some of those reductions – for the purpose of forcing efficiencies and some self-reliance – and not raise taxes a little?

Figure 2 indicates taxes and incomes in the 2015 financial year as a percentage of all government income.

It is generally accepted that the tax regime ought not to penalise wealth creation unduly; after all, it is to everybody’s benefit to create a bigger economic cake to share, be it through corporate investment or workers, both carrying the weighty end of taxes. It is better to tax spending, that encourages savings that also lead to new investment capital to grow the economy.

Tackling the problem

Hopefully the inquiry can put to the public some simple questions: reduce benefits, or raise taxes a little, or a bit of both. If raising taxes, which one or ones go up, and which if any go down (e.g. some corporate taxes to maintain competitiveness in Asia)?

None of the options are really tough; they just take intelligent reasoning, sensible selling to the public and courage.

John Key has done it in New Zealand, Mike Baird showed those qualities in the NSW March election win in standing up for privatisation – admittedly with a generous seats advantage in the outgoing parliament. And both ALP and Coalition governments have taken action on major reforms over the quarter century to 2007. It can be done.

We can only hope politicking, vested interests and narrow-mindedness take a back seat in this inquiry. On recent performance, that is unlikely; and more’s the pity.

But we can hope.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content