The 4 pillars banking policy must be updated if Australia is to become internationally competitive and successful, suggests Phil Ruthven AM.

Australian banks are sometimes seen as fair-weather friends in their dealings with customers, accused of being more interested in profits than people. More recently, they were labelled cheats in the banking Royal Commission. However, no bank has ever made the list of the nation’s 100 most profitable large businesses, nor the best 200. Only three banks scraped into the nation’s 500 most profitable large businesses during the three years 2015–2018, according to IBISWorld.

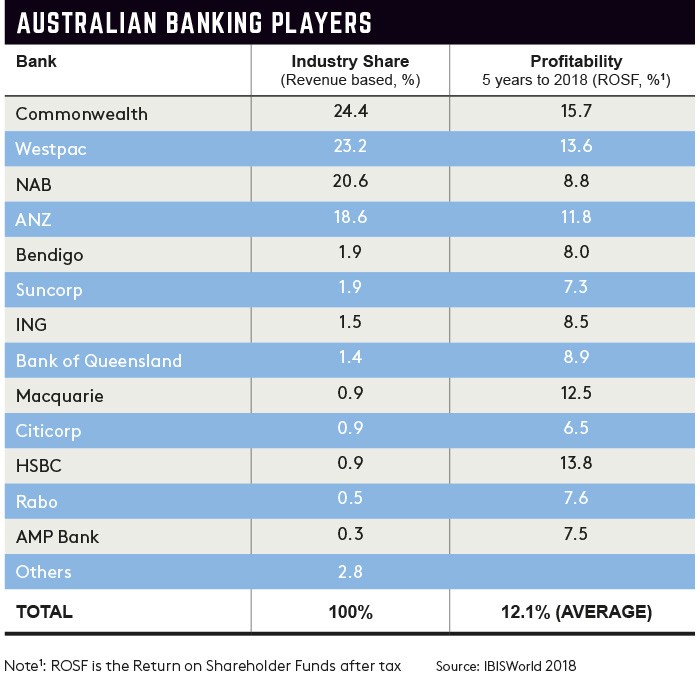

The most profitable, the Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA), ranked 366th — with a return on shareholder funds after tax of 14.8 per cent (15.7 per cent over a five-year period). Our banks collectively averaged 12 per cent, this in a world where best practice for any large business has been 22 per cent over the past 50 years — as set by the US corporate world where more than one in five companies achieve that over any three-year period. In Australia, only one in seven of our largest corporations make it.

Banks in Australia — and many nations — are nowhere near world’s best practice profitability due to their positioning, a lack of differentiation or uniqueness, and loss of focus (reflected in unsuccessful diversification). Basically, it’s difficult for them to be masters of their own destiny.

Dominating the market

Analysis by IBISWorld of the nation’s largest enterprises within their respective industries over the past 45 years shows conclusively that there are only four positions from which a business can legally assume market domination.

The lowest of these is a 0.1 per cent share of the revenue of an industry class (of which there are 509 in Australia). In this safe position, there are few players of a boutique or exotic nature with an expensive, fashionable, top-end product, be it in the form of goods, or services.

The next safe position is a one per cent revenue share, an ultra-niche position where players seek a 50–75 per cent share of a narrow product group or customer segment. Constant innovation is critical for these players.

Then comes the niche player, which has a five per cent share of the industry’s revenue, but is the biggest player (more than 50 per cent) within a product group, industry or market segment. Again, innovation and research and development are important.

The last safe position is as a major, with a 25–75 per cent share of an industry’s revenue, a more than 35 per cent share of the chosen segments of participation in the industry class and economies-of-scale advantages rather than feature ones.

There are several no-man’s-land zones where it is virtually impossible to achieve world’s best practice profitability:

- If your business has more than 75 per cent share of industry revenue (you end up with dis-economies of scale with products and customers that lose you money).

- If you have between five and 25 per cent and are sandwiched between major and niche players.

- Wedged between niche and ultra-niche operators.

- Trapped between boutique and ultra-niche enterprises.

Fixing the problem

So, where do Australia’s banks fit in this spectrum? Banks have a special place in society. The federal government’s “four pillars” policy, dating back to 1997, means none of the four major banks can merge. It is almost impossible under this policy to have a major player, although CBA is close.

There are no niche players. There is no ultra-niche player. Whether successful boutique banks (ME Bank, Heritage) emerge, time will tell. None is able to position itself to generate world’s best practice profitability.

The original 1990s policies under the Keating Labor government — six pillars (including National Mutual and AMP), then four pillars — have made sure of that. Often called the “golden handcuffs”, the policy stops the organisations from going broke, but also makes it difficult for them to differentiate themselves from competitors: all being in the no-man’s land of five to 25 per cent with market shares.

In turn, without uniqueness — another vital rule of success — none has been able to successfully expand offshore; or master the skill and risk-taking support of promising new enterprises, as happens in the US.

Getting competitive

The Productivity Commission, in its 2018 report on competition in the financial system, argued the four pillars model was redundant.

“It is an ad hoc policy that, at best, is now redundant as it simply duplicates competition and governance protections in other laws,” said the Productivity Commission. “At worst, in this consolidation era it protects some institutions from takeover [which is] the most direct form of market discipline for inefficiency and management failure.”

In explaining this logic, Productivity Commissioner Peter Harris quoted the 1997 Wallis Inquiry, which argued that the pace of change is likely to accelerate, thus any static policy may become outdated.

“We would not argue that three or two is better than four (or six, covering insurers too, as it was back in the 1990 decision that gave birth to this tenet of policy faith),” said Harris. “The problem with such policies is the comfort that they induce. In this case, the false hope that banks must be competing because we have, and will always have, at least four of them.”

Post-Wallis, banks went on to diversify, looking for more growth and profitability. That hasn’t worked, either, as it breaks the rule of focus (one industry class). Indeed, the diversification may have inadvertently led to the unconscionable conduct identified by the Hayne Royal Commission — due to the span of control problems, and growth and profits with whatever it takes.

If we want a competitive and internationally successful banking industry, then neither the four pillars policy nor the “perfect competition” rules will work. We need a few majors (over 25 per cent industry share), three to five niche players and a few ultra-niche players as icing on the cake. Indeed, we need tighter focus, economies of scale and uniqueness as well as better positioning.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content