With the outcome of an ACCC inquiry into water markets due in November, is it possible for Australia to resolve the tensions between upstream and downstream enterprises? Adam Courtenay writes.

About three years ago, famous Wall Street guru Michael Burry had a great new idea. The man glorified in Michael Lewis’ book The Big Short, and its 2016 film adaptation, for making a killing on the US housing crisis in 2008, sold out everything in favour of one commodity — water. It sounded brilliant because water was becoming scarcer — climate change was coming and demand would soon outstrip supply. Ergo, water would one day be like gold.

But Burry never actually invested in water itself. The trading system in America is too archaic and overly cumbersome. So he invested in almonds as a “water-intensive” commodity. He has been extremely quiet about the state of his agricultural/water assets ever since.

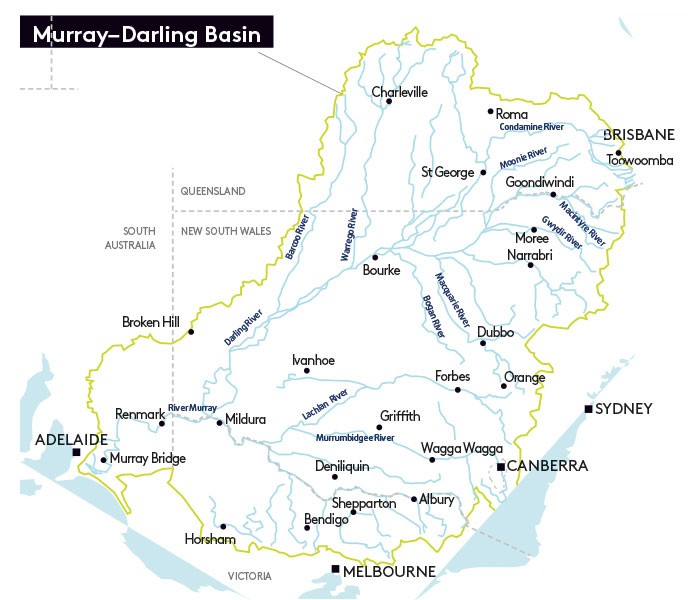

Australian farmers might have laughed at Burry’s big idea, as they’ve been trading water since the 1980s. The system that underpins the southern Murray-Darling Basin (sMDB) market for water — where 90 per cent of the nation’s river/dam water is traded — is the most advanced in the world. It is also one of the most complex commodities to trade, and the system that runs it has come under increasing regulatory and political scrutiny. Recently, there has been controversy surrounding dubious government water buy-backs, but the farmers are more concerned by the ongoing Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) Murray-Darling Basin Water Markets Inquiry — due to deliver its interim report on 30 June. Lack of transparency is one of the issues at the heart of the inquiry.

It is no coincidence that the inquiry was instigated in the midst of a two-year drought. As climatic conditions have worsened, questions about marrying a market-based system to natural hydrology have increased. The corpses of millions of fish in Menindee, NSW, in January 2019, signalled the Darling’s woes, but farmers’ concerns are different. The drought has blighted the land, but it has also exacerbated envy. Tensions have heightened between the “haves” and “have-nots” on Australia’s most important river system, which drains about one of every seven hectares on the continent. The sMDB has been suffering from a lack of winter rainfall, which has been on average 26 per cent less than it was in 1974.

Since the Millennium Drought (1996–2010), many farmers have sold their water entitlements back to the federal government for environmental purposes — or to bigger agricultural concerns. A region once the haven for farmers producing the “bulk commodities” of wheat, rice and cotton, is now looking very different. The new kids on the block are almond, olive, avocado, grape and citrus estates — the most profitable and exportable agricultural products. Others have joined them, speculators and big financiers allegedly soaking up all the water and ramping up prices.

The basic unit of water trading is the “permanent entitlement” that gives perpetual access to a share of a “space” in a dam or storage. You can also trade allocations — also known as temporary water or yield — which is the volume of water allocated to the entitlement on an annual basis, based on storage and rainfall. There are nine trading zones in the sMDB, which are hydrologically linked, enabling trade of both entitlements and allocations across many different catchments.

But water is not equal. In the 2018–19 season, SA holders of Murray high-grade permanent water got a 100 per cent allocation, effectively “filling their buckets”. The buckets of much cheaper, general security water rights in NSW were allocated a mere three per cent.

All players are operating in a market with no central exchange for the buying and selling of entitlements or allocations. There is no need to name beneficial owners in transactions, no central records of volumes, and no clear price discovery. Foreign ownership of water entitlements within the sMDB is now at 9.4 per cent, but who or what are they?

“We need to know what everybody else is doing and have it written on the record,” says Lex Batters, CEO of H20X, which runs one of the four exchanges that provide some price transparency to the market. “The market is full of dark pools — you only have to look at the hugely different prices quoted. We need to see regulation of participants becoming simpler. It’s still the Wild West.”

Murrumbidgee River

Murrumbidgee Irrigation (MI), which provides irrigation water and drainage to more than 3000 landholdings, is one of many organisations that presented its findings to the ACCC Murray-Darling Basin Water Markets Inquiry. The company feels the market is rife with anomalies that need to be ironed out.

Like others, it is interested in transparency of information, says chair Nayce Dalton, but there are other concerns. In particular, MI is looking at the 100GL Murray-Murrumbidgee Inter-Valley Trade (IVT) limit and pre-2010 “tagged trade” exemptions.

The IVT limit is about restricting trade between the Murray and the Murrumbidgee rivers — it is physically impossible to return Murray water back to the Murrumbidgee, so there’s a limit on trades in that direction. But certain traders who have “tagged licences” can do this. MI CEO Brett Jones says this is iniquitous. When trade is closed to everyone else, these licensees can still “move” water across valleys. “It’s a bit like having a stock exchange where trading has ceased and yet certain people are allowed to trade out of hours,” he says. “Some of this water legislation is very old, with so many layers, exemptions and anomalies.”

Those with tagged licences have doubly exceeded the IVT limit for the past two years, according to Jones and Dalton. Both want more transparency on water pricing and volumes, but not at the cost of irrigators. “We’re not calling for a central exchange, but centralised information on recent sales,” says Jones.

Part of MI’s responsibility is to process trades — the entity that moves water from sellers into buyers’ accounts. MI has to process the water documents going back and forth from NSW, Victoria and SA, and there are calls from users for MI to have an electronic system. Jones says this would mean paying for everybody’s trades, including those outside the Murrumbidgee. “We would need platforms, registries and the capacity to do all the auditing and compliance,” he says. “What happens if we make a wrong electronic post and we’re sued for misleading the market? We’re all for a centralised information exchange, but not forced through irrigation corporations at the cost of irrigators.”

Water trading has long been considered a closed cabal, the preserve of in-the-know brokers uninterested in price regulation. In other words, it’s a market ripe for arbitrage. Rob McGavin, executive chair of Boundary Bend, which grows more than 2.2 million olive trees across two Victorian sites, says non-water users should be expelled.

“This is a limited resource,” he says. “It’s meant to be held in government storage for the nation’s economic gain. How can we have growers on their knees trying to afford to buy water while others hold off selling because they think it might be worth more in two months?” Those who did so lost out big-time. Prices have fallen from about $800/ML to around $200/ML now. This highlights the risk of such a strategy.

Of course, when the rains soaked the entire region in fiscal 2016, nobody was complaining. They weren’t complaining in 2017, either, when there was enough water left over from the previous year and government water authorities — which estimate the allocations — started to turn the taps clockwise. When it didn’t rain in 2018 and 2019, water authorities simply cut off allocations for the cheaper general security entitlements. Not a drop could be used. What was left to buy and sell were allocations on high security entitlements. By mid-2019, just before the big seasonal demand for crop irrigation, prices for temporary water went crazy. “Yields that were up five-fold over two years leapt to tenfold over three years,” says Batters.

Chris Olszak, director of water consultancy Aither, says Goulburn Valley Water allocation prices moved from $47/ML in 2016–17 to $99/ML in 2017–18; $374/ML in 2018–19 to $700/ML in 2019–20. That’s a 15-fold increase during the period. Across the sMDB, average entitlement prices also increased. They were up on average 24 per cent from 1 July 2018, to 1 July 2019, according to Aither’s Entitlement Index. In the latter part of 2019, this increased by another 11 per cent as the big dry continued. From January to June this year, prices have dropped by as much as 10 per cent.

Meanwhile, McGavin has watched his annual water bill for Boundary Bend grow from $3.9m three years ago to more than $25m in 2019. Something has to give, he says. “We’ve had to halve our capital projects and suspend dividends to shareholders, but the hardest part of all this is guessing what will happen tomorrow,” he says. “We’re in this as a business, and yet the water prices are not transparent. In this market, you don’t know who you’re bidding against.”

Haves and have-nots

On the lower side of the Murray, below a narrow section known as the Barmah Choke, near Shepparton, many of the large permanent plantations reside. The water they request is released from the Hume and Dartmouth dams hundreds of kilometres upstream.

Closer to the dams are rice growers, dairy farmers and cotton growers on the upper Murray, above the Choke, watching on haplessly while huge volumes of water are released to slake downstream demand.

When water approaches the Choke, it passes the narrowest stretch of the river through the Barmah-Millewa Forest on the NSW-Victoria border.

Here, it slows down. Only 9500ML a day can pass through, but demand is between 7000–12,000ML. The area around the Choke floods, and there has been considerable environmental degradation. How do the farmers above the Choke feel when water they can’t afford is wasted?

This kind of outcome is what happens when markets rule over hydrography. In Asia, there is an insatiable demand for Australian citrus, table grapes, almonds and wine. The many free trade agreements throughout the region have opened the market. High prices for these commodities mean producers can afford high water prices. But to keep their trees alive, permanent horticulturists must access this water.

Euan Friday, chief financial officer at Kilter Rural, says there’s been an 11-fold increase in total area of almonds planted in Australia since 2000. Friday estimates that one hectare of young almond trees planted now might need 2–3ML of water per year. By the time these trees mature in six years, the same hectare will need 14–15ML. By 2028, an extra 200–650GL of water will be needed without planting a single new tree. Kilter’s own estimates are that by 2027–28, almonds alone will be using 40 per cent of the water available in the sMDB in a dry year.

Is it an “us versus them” situation between permanent crops and other farmers? Not exactly, says Olszak. It really is about which irrigators have stronger balance sheets and more flexible production systems. “Many irrigators are switched on to make a choice each year — do they use the water or sell it?” he says. “Is it more economic to buy in fodder than water the grass? When water is so expensive, it might be more profitable just to sell it on.”

The key metric, says Friday, is gross margin per megalitre. This is the gross margin an enterprise can generate per megalitre of water used, which determines how much they can afford to pay for water while still breaking even. “It’s the revenue and cost structures that matter,” he says. “Look at the gross margin you can achieve with one meg of water used in an enterprise and that’ll tell you how much that enterprise can afford to pay in the market.”

When water allocations rise to around $300–$350 per megalitre, rice growing becomes uneconomic. But who, these days, is simply a rice grower? Robert Massina, who farms rice, grain, lamb and wool between Finley and Jerilderie in the southern Riverina, says he tends to concentrate on winter crops such as wheat, barley, canola and oats. He is president of the Ricegrowers’ Association of Australia and yet, ironically, says he has not been growing rice over the summer when water prices escalated. Unlike permanent horticulturists, he can be nimble. “If you own 100 acres of farmland, it could be 20 per cent rice and the rest wheat, barley and livestock,” he says. “We’ve learnt to be multitasked.”

Water has no doubt created a growing disparity between the haves and have-nots. Some simply shrug it off, saying it’s just a factor of change. Kim Morison, managing director of Argyle Capital Partners and a veteran of agricultural and water fund investment, agrees there are lots of challenges in communities. But he points to the many profitable operations and developments in communities such as Griffith, Mildura and Renmark. “Good things do happen,” he says. “There’s been a rise in export markets and in per capita wealth. The markets in Asia are demanding our crops and we’re getting handsome prices. That’s what’s driving the returns for farmers.”

What is the ACCC looking at?

Chris Olszak from water consultancy Aither is not overly worried by the concept of speculation in the water market. “Speculation can be long or short; it happens both ways,” he says. The risks are simple — it can rain when we least expect, as it has done from December until now.

Rob McGavin from Boundary Bend says a farmer can own water in the Murrumbidgee River and transfer it for a zero-dollar value on the Murray. Deals can be done off-market and nobody will ever know. “How can we deal with off-market trades? We would like to see a single exchange so people have real-time transparency and know what’s going on,” he says. Many people have pointed the finger at fund managers, particularly at Duxton Water, the listed non-farming entity that has water entitlements worth $256m — around 75 billion litres’ worth. Duxton has been accused of “carrying over” more water rights in comparison to their annual consumptive use, therefore driving up prices.

Lex Batters at H2OX doesn’t believe Duxton is hoarding. “We don’t see them sitting on water and pooling it, hoping the price goes up — they don’t have that kind of risk appetite,” he says. “If you buy 1000ML of Murray water at $750 a meg, that’s $750,000. If it rains, they won’t get their money back.”

For its part, Duxton says it is a long-term investor, leasing out around four-fifths of its entitlements to farmers. The company’s 75 billion litres still equates to less than one per cent of entitlements on issue.

The issue of carryover water is contentious. Water not used one year can be carried over to the next in varying degrees. In NSW, only 50 per cent of unused water from a dam can be carried over, but in Victoria, it is 100 per cent. There are risks associated with this theory because if there are heavy rainfalls and dams spill over, the carryover is defunct. But in a dry year, it is seen as a way to make money.

“It’s become a high-reliability product for speculators to carry over water from an average rainfall season into a drier season — and potentially make a lot of money,” says Robert Massina, president of the Ricegrowers’ Association of Australia. “In some cases, if the dam doesn’t spill, they can keep carrying it over year after year until the prices are high enough to sell.”

There are ways to rort the system. “I can pay someone with a Victorian water license to put it on their account so I don’t have the risk of it spilling,” says Massina, who is not alone in believing the free market model does not account for the realities of conveying water vast distances. There are choke points along the Goulburn and Murrumbidgee, as well as the Murray, which limit the volumes of water that can be conveyed.

“Since 2008, the in-stream deliverability of water in the Murray has reduced by 21 per cent, or 1500ML per day, making the Barmah Choke even more prone to overflowing into the surrounding land, further increasing the risk of conveyance losses,” he says. “All of this needs to be looked at again. We need all states coming together to work through the solutions.”

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content