Google turns 20 this year, Facebook 14, Twitter 12, Instagram 8 and Snapchat 7. As their power increases they are coming under greater regulatory scrutiny from the ACCC.

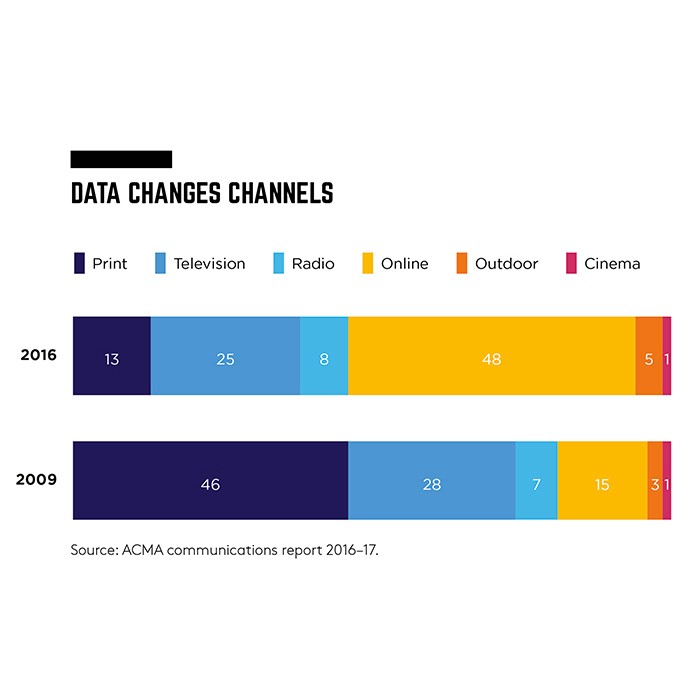

Search engines and social media platforms have disrupted the advertising and media landscape globally, but at the same time they have provided innovative and useful services for individuals and fresh avenues for businesses to connect and engage with consumers. Attempts to rein in their activities may boost competition in some quarters but have detrimental knock-on effects for businesses in others.

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) is currently evaluating, through its Digital Platforms Inquiry (DPI), the impact these digital platforms have had on the nation’s media and advertising landscape. Its terms of reference require the ACCC to assess “the impact of digital search engines, social media platforms and other digital content aggregation platforms (platform services) on the state of competition in media and advertising services markets, in particular in relation to the supply of news and journalistic content, and the implications of this for media content creators, advertisers and consumers”.

The review will also explore the impact technology and information asymmetry can have on consumers at a time when digital platforms hold all the data aces.

The issue of data asymmetry was thrown into sharp relief by the recent revelation that British consulting firm Cambridge Analytica had harvested the personal details of millions of Facebook users — without their consent — to develop highly targeted political campaigns for its global clients.

Facebook’s mea culpa was muted. “We need to do more to safeguard your privacy, so we’re taking action on potential past abuse and putting stronger protections in place to prevent future abuse of our platform,” the social media giant told its users.

While Facebook fiddles with its terms and conditions, stronger initiatives are already underway to rebalance data ownership in Australia. The Productivity Commission’s report Data Availability and Use recommends individuals be given more control over their personal data. At the start of May, the federal government signalled its acceptance for those recommendations and announced a National Data Commissioner role to oversee a new data access framework.

Meanwhile, the move to open banking is gathering pace. In February, the federal government released a paper — written by the Open Banking Review and led by King & Wood Mallesons partner Scott Farrell — on how an open banking regime should be implemented so that it provides consumers with greater data rights.

Information as a commodity

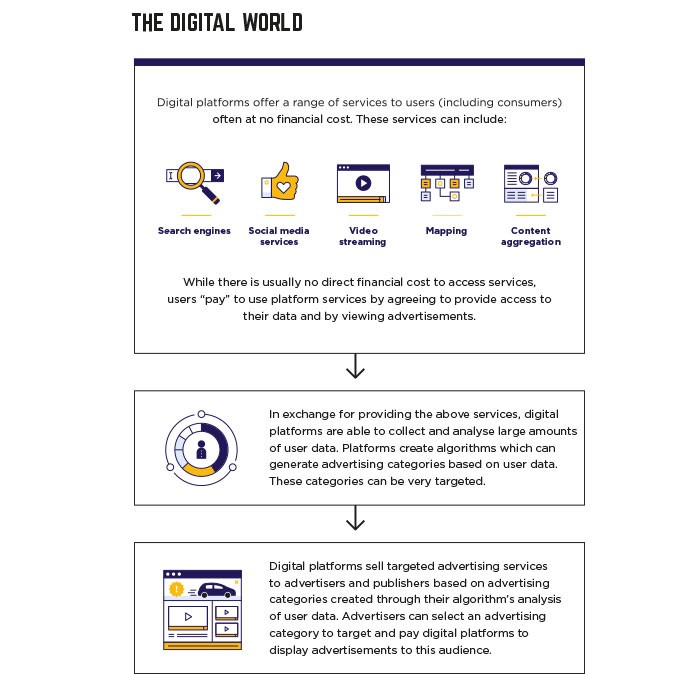

The DPI issues paper notes that, “Digitalisation and, in particular, consumer use of digital platforms has led to an exponential increase in the generation and collection of consumer data, and big data technologies have enabled the extraction of commercial value from this data through high-velocity data capture, discovery and analysis.

“These technologies may be harnessed by digital platforms to create new or improved products and services that better target the individual needs of consumers and advertisers. However, the use of large sets of personal data for commercial purposes raises competition and consumer concerns, as well as broader policy issues.”

ACCC chair Rod Sims says, “Our job will be to get on top of what’s happening and let consumers know what is going on. As we get new technologies, we must understand what they can and can’t do, and whether they’re being used in a way that breaches the Competition and Consumer Act 2001 (Cth).”

Consumer protection

Protecting consumers from overly powerful and data-rich internet behemoths is something that regularly preoccupies Natasha Tusikov, assistant professor in criminology at Toronto’s York University and a visiting fellow with the School of Regulation and Global Governance at the ANU.

“It’s important for people and company directors to remember that these companies run on data — it’s their lifeblood,” says Tusikov. “The more personal data they have, the more they commodify that to sell profiles — and sometimes those profiles are embarrassing or offensive. Companies are amassing data not even knowing what to do with it,” she says, using tone-of-voice collections as an example.

She believes that in light of the Facebook revelations, consumers are now taking more heed of what data they provide, to whom and for what purpose. “Companies will need to think about it.”

Regulating big data

Tusikov is more optimistic than she was 18 months ago that some form of regulatory control could be imposed on internet giants, largely due to the focus on Russian interference in the American presidential election and the mainstream debate that ensued. And it’s not just Facebook copping flak. “Google is the largest digital advertiser in the world — should Google be broken up?” she asks.

Anti-trust action against technology-charged juggernauts has precedent — witness the 1982 break-up of AT&T into seven Baby Bells to promote telecommunications competition in the US.

“I think we are in the same territory as we were when the anti-trust legislation was introduced in the US for the oil companies and big telecoms,” says Dr Simon Longstaff AO, executive director of The Ethics Centre and a member of the AICD’s Corporate Governance Committee.

“Between them, Google, Amazon, Facebook and Apple have a degree of control in the commercial marketplace that the British East India Company could only have dreamed of. They are just so dominant and see so much opportunity through scale that they move into areas where the capacity for there being a genuinely rich ecology gets squeezed out in order for people to have the efficiency dividend that their platforms offer.”

Longstaff queries the suggestion that digital platforms such as these allow for a different sort of innovation at the edge of an ecosystem that might, in fact, promote competition and consumer choice. “When I am being naively optimistic, I would love to think that these big platforms are doing the same thing and being as much changed by what is happening at the periphery as what is at their core. But my suspicion is, that is not what happens — that their scale and efficiency dominate the market to the point where innovation is constrained by their rules.”

Whatever the outcome of the DPI — and that won’t be clear until after the ACCC hands its report to the Treasurer, scheduled for June next year — Rod Sims says an amendment to the Competition and Consumer Act in 2017 introduced a workable “misuse of market power” condition that has given the ACCC teeth regarding any use of data-enabled algorithmic trading to keep competitors out of the market.

“To illustrate that, if you had algorithms that were owned by different companies that started to communicate with one another to push prices up, the ‘concerted practices’ law could now deal with that, where previously we couldn’t. Alternatively, if you have companies using algorithms to keep competitors out, now we have a law to deal with that: the new ‘misuse of market power’ provision.”

Tusikov believes giving individuals agency over their data, rather than leaving it in the hands of technology companies, might prove the real game changer. At present, a typical internet user would need to spend 200 hours a year reading website privacy policies to really understand how their data was being used, according to Tusikov. If data ownership and agency can be legislated, she says, it will make clear “what belongs to the individual and under what circumstance companies can use and access data, with or without permission”.

If that takes hold, then the world changes dramatically for any business that collects, stores and uses personal data — regardless of the findings of the DPI.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content