Public trust is the not-for-profit (NFP) sector’s most valuable asset. The sector has enjoyed historically high levels of trust which it has leveraged to make its substantial contribution to the Australian community.

Public trust is the not-for-profit (NFP) sector’s most valuable asset. The sector has enjoyed historically high levels of trust which it has leveraged to make its substantial contribution to the Australian community.

However, in recent years, trust has been in decline globally, including in the NFP sector. The Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission’s Public trust and confidence in Australian Charities 2017 report (the ACNC Report) has observed an erosion of trust over a number of years. Trust in charities has declined from 37 per cent in 2013 to 30 per cent in 2015 and down to 24 per cent in 2017. Other research on this topic has borne similar results.

Addressing declining trust

It appears that while the significance of trust is well-established in the NFP sector, there is little evidence of directors taking an active approach to addressing trust through active governance approaches.

Our own research on trust identified culture as the most significant issue relevant to trust for NFP organisations.

Figure 1

The most critical issues relating to trust for my organisation are:

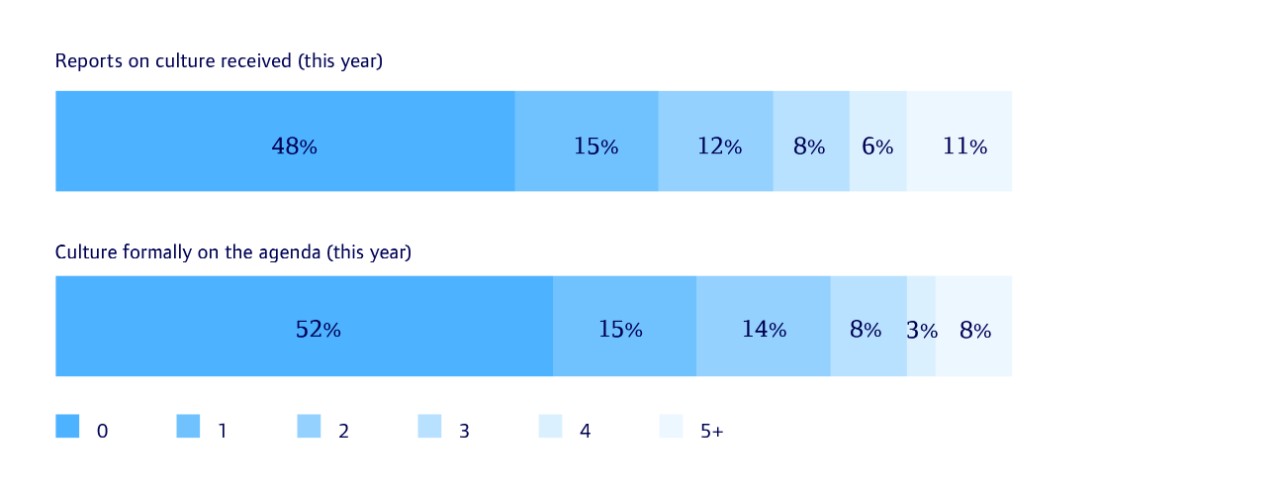

The AICD investigated culture in our 2017 NFP Governance and Performance Study. This study found that directors generally felt that the culture of their organisation was strong (most directors rated their culture above 8 out of 10). However, very few directors received reports on culture and a majority didn’t even have it as an item on their agenda.

Figure 2

Number of times discussed in a year

It is clear that directors appreciate the importance of culture and its relationship to trust. However, the great majority of NFP boards are not governing trust. If culture is the most critical issue relevant to trust, but it is also not on the agenda for boards, this represents a significant blind spot in the practice of directorship among NFPs.

Questions for directors:

- How does our culture contribute to (or erode) trust in our organisation?

- Do we know what our culture is and how do we know this?

- What strategies are in place to maintain and, if necessary, change our culture?

The diversity of distrust

Trust in NFPs is driven by a number of factors and varies significantly based on demographic indicators and association with the sector. According to the ACNC Report, the key influencers of trust are an individual’s belief in an organisation’s mission and transparency about use of resources, particularly its fundraising activities.

Fundraising conduct is a critical issue for trust in the NFP sector. Recent media attention has focused on the proportion of funds paid to third-party for-profit fundraisers, as well as the behaviour and employment conditions of face-to-face fundraisers, sometimes called ‘charity muggers’ or ‘chuggers’.

The ACNC Report found that 45 per cent of respondents did not trust charities that paid salespeople to raise funds on their behalf. The report also found that since 2015, fewer Australians trust charities to apply their donations to a charitable purpose and to be ethical and honest in their fundraising.

There can be no doubt that conduct in fundraising can erode trust, and indeed may have already done so.

Donors expect that their donation will be applied, in the main, to the purpose for which it was collected. While there might be some flexibility in how these donations are collected and used (even the leanest of organisation will have some administration costs), there is a limit, and the consequences for transgressing this expectation are extreme.

Learning from the United Kingdom

In 2015 a fundraising scandal erupted in the United Kingdom (UK) after the tragic suicide of Olive Cooke, Britain’s oldest poppy seller. Mrs Cook was reported to have felt “distressed and overwhelmed” by the 3,000 mailings she received annually from charities soliciting donations. A report by the Fundraising Standards Board found that at the time of her death, 99 charities possessed her details, 70 per cent of which had obtained these details via a third party.

Questions for directors:

- What oversight do we have of our fundraising activities?

- How do we govern those collecting on our behalf?

- Would our stakeholders support the way we collect and use donors’ funds?

The ensuing scandal was ruinous to the reputation of and public trust in the UK NFP sector. A report released by the UK Charity Commission (Public trust and confidence in charities 2016) showed trust to be at its lowest since data was recorded on this topic in 2005. The most influential causes of this collapse in trust had been media reports about charities’ operations (33 per cent) and how charities spend donations (32 per cent).

The reputational damage was significant enough to warrant the attention of the parliament, resulting in an inquiry into ‘The 2015 charity fundraising controversy’. The inquiry singled out directors of charities as failing in their duty to effectively govern fundraising and concluded in one line: ‘It would be a sad and inexcusable failure of charities to govern their own behaviour, should statutory regulation became necessary.’ Despite this, the inquiry also observed that the vast majority of charities were not involved in misconduct.

Nevertheless, additional regulation followed, media scrutiny of fundraising practices in the UK persists and trust continues to decline. This should serve as a reminder to boards that government is willing and able to intercede where trust is eroded to critical levels.

Lessons for NFP boards

Trust is an invaluable asset that the NFP sector shares as a collective and which has experienced some damage in recent times. The hard truth for NFP directors is that while we may not be, as individuals, responsible for the damage done to trust, we are influenced by it as a collective. By extension, we are also collectively responsible for restoring this trust.

NFP directors identify the top three factors most critical to building trust as:

- Communicating and engaging openly with stakeholders;

- Transparency of business practices and decision-making; and

- Understanding the issues that matter to stakeholders.

Our research shows that NFP directors do not understand or respond to trust differently to directors in the private or public sector. It is clear that simply undertaking work that is beneficial to the community is not enough to build (or restore) trust.

NFP directors must see themselves as the protectors of trust, both in their individual organisations and across the broader ecosystem. They must be active in exercising their governance responsibilities to protect trust and to imbed consideration of factors that affect trust in their decision making.

The relationship between NFPs and their donors should be in sharp focus for all boards. Today’s donors have access to detailed information about how an NFP uses their contribution and this increased transparency must be accounted for by boards.

Importantly, boards must be satisfied that they have appropriate governance oversight over any activities that have the ability to affect the public’s trust. Trust is won and lost in the satisfaction or otherwise of stakeholders’ expectations, and these should be understood and reflected in the governance of all organisations, NFP or otherwise.

Questions for directors:

- What are we doing to maintain trust in our organisation?

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content