Phil Ruthven AM argues that Australian companies should be wary of becoming too focused on the customer, to the detriment of their intellectual property and brand.

In the wake of the banking Royal Commission, there has emerged a strong focus on the customer. Commissioner Kenneth Hayne AC QC found that “providing a service to customers was relegated to second place. Sales became all-important”.

In the recent KPMG AICD survey, Creating Value and Balancing Stakeholder Needs, directors rated customers and clients as their “most significant” stakeholders (360 out of 612 respondents). “Organisations are finally embracing the idea of the customer being king and are now truly putting customers at the centre of their thinking,” KPMG chair Alison Kitchen MAICD noted in the report.

There is a real danger in treating customer focus as the holy grail of success. It isn’t and never will be. However, we have to have a unique product to win the minds and the credit cards of customers. This is where most Australian businesses fail to deliver — here and overseas. So, how were we seduced into thinking customer focus was the be-all and end-all?

If there is one slogan or archetypal phrase that separates the new age from the industrial age, it is “market (or customer) orientation”. Economies changed from being supplier-driven and dominated to being buyer-led and dominated. The revolution of consumer power has, of course, extended into the services economy. This revolution has led to the extraordinary situation in 2019 where households spend more on outsourced services from the home (an estimated $500b) than on all retailing, including motor vehicles (about $420b). Indeed, all goods now account for just 22 per cent of gross household income compared with 62 per cent at the time of Federation in 1901.

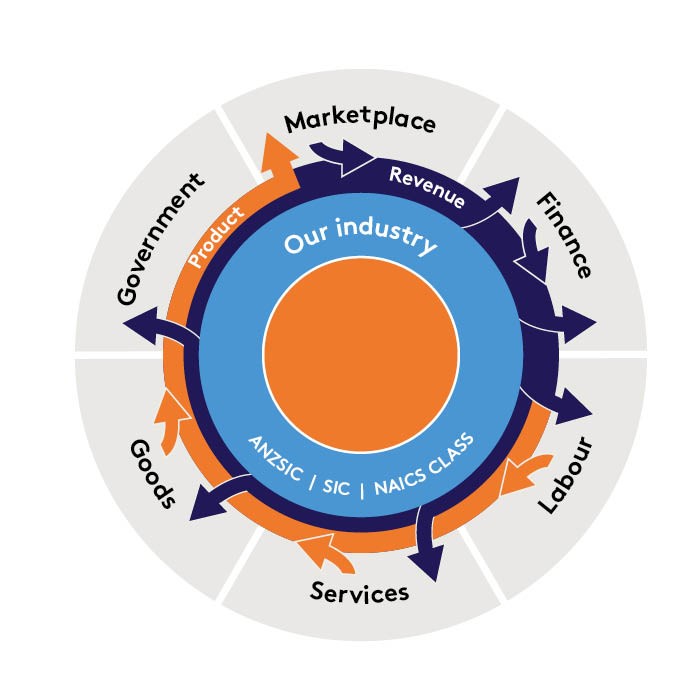

This figure reminds us of the outside world we deal with in monetary terms in a business and in the industry at large, including our competitors. There is a new respect for the market — being the source of revenue — and a thirst for knowledge to win customers. Therefore, a condition of survival is that we know our market intimately — size, growth, composition, geography, demography and psychographics (for consumer products) and distribution.

Of course, we must ensure our costs via external environments do not exceed our revenue in profit and loss and cash-flow terms to ensure solvency, profits and reinvestment.

This doesn’t mean success depends solely or primarily on customer or marketing orientation. Even though successful businesses might say they own, or want to own, a customer or market segment, they can’t. Customers own themselves.

What we can and must own are our products, their uniqueness and the industry segment we operate in. This is our intellectual property (IP), helped by a thorough ongoing understanding and forecast of customers and the market segments in which we participate and compete.

Anticipating customer preferences and habits can be tricky, and left-field entrepreneurship can decimate long-standing businesses.

Amazon transformed bookselling with online retailing and electronic books. In expanding its range of products, it has become an online retail department store, a third iteration after the traditional formula of the late 1800s and the one-level discount formula of the late 1960s. Alibaba is an online shopping centre, as is eBay.

Uber is displacing taxis and limos. It is, of course, in the travel agency industry — not in taxis or rental cars. It arranges your trip, takes your money and gets a vehicle to take you there. Our retail car industry is also on notice, with driverless electric cars on the way.

The message is: be very careful in developing a strategy based on customer and market orientation that is a means to the end of being master of your own destiny in a customer or market segment. Being master of one’s own destiny means owning a unique product — or industry segments of products — that in turn enable a business to “own” a market or consumer segment for as long as it remains unique or where the provider is by far the lowest-cost producer — and has some IP as well as economies of scale.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content