Waning audience numbers and financial strains forced Circus Oz in 2016 to reinvent their organisational strategy. Now, the 41-year-old organisation is thriving.

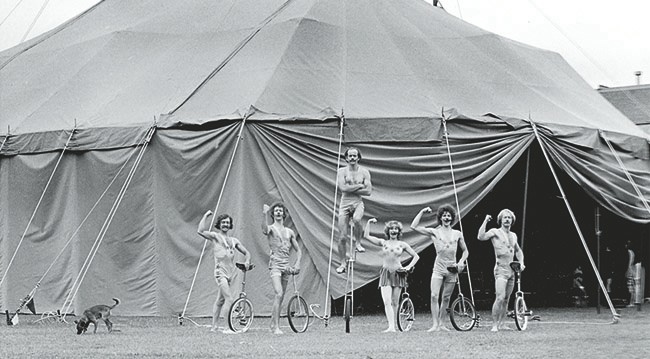

When Circus Oz first took the stage in 1978, it redefined circus in Australia and around the globe. The troupe did not use performing animals in the ring, a practice viewed as cruel and demeaning. Gone were the glamour girls introducing male performers. Instead, strong women worked with men in every category of circus art form — sexy, but not sexist. Rather than cranking out hackneyed recorded tunes, the circus included an orchestra playing original music.

The performances inspired awed gasps as well as laughter. Word spread like wildfire, even without the benefit of the internet or social media. Audiences in capital cities, long disengaged from outback showmen, flocked to see this new kind of circus.

Circus Oz took the world by storm.

Midlife crisis

As the troupe ended its fourth decade, the formula began to fail. Audiences were falling in regional tours and, dishearteningly, even in Melbourne, Circus Oz’s hometown and most loyal fan base. The Big Top shows seat about 1000 people, yet two performances in Sydney, in 2015, attracted only 926 people combined.

The circus made a loss of $268,000 in 2012 and another loss of $195,000 the following year. In 2014, a grant boost and doubling the publicity spend to more than $1m saw a modest profit recovery to $45,000, after extraordinary items. However, in 2015, it plummeted again to a loss of $184,000.

Canadian company Cirque du Soleil, which formed in 1984, had adopted similar philosophies and grew during the 1990s and 2000s, stealing audience share. It was time for change.

New home, old problems

Nicholas Yates, who became chair in 2017, has overseen the transformation of this creative company as it trawled through the worst of times. The company has undergone a complete revamp of its program, resulting in a resurgence of engaged audiences and a net surplus of $98,000 in 2018.

But it hasn’t been an easy ride.

Yates joined the board in 2010, at the invitation of the then chair, Wendy McCarthy AO FAICDLife. Trained as a mechanical engineer, Yates had spent decades as a project manager in construction with Lendlease and as a CEO at APP Corporation and Transfield Services. McCarthy helped the circus move from a tired old warehouse in Port Melbourne to a $10m purpose-built headquarters in Collingwood. The building project finished on time and on budget.

“I’ve got to that stage through experience whereI can pick the eyes out of where the risk is and steer the ship from the bridge rather than from the engine room,” says Yates. He adds that the answer lies in a detailed brief, ensuring nothing slips through the cracks with the design and construction management process.

Unfortunately, Circus Oz’s new home didn’t solve the financial problems. “When I joined Circus Oz, we had a format: a Big Top show in the middle of every year, which was our primary income, plus a four-week season at Birrarung Marr [on the north bank of Melbourne’s Yarra River],” recalls Yates.

“We recycled that show the second year and took it to Sydney [biannually]. When I joined, the shows were spectacular and we had huge audiences. Then you see the graphs [of audience numbers] stop.”

Yates says a closer look at the shows revealed problems. “Probably, the artistic vibrancy of the shows started to drop off.”

The 2015 season was the final one for artistic director Mike Finch, who retired after 17 years at the helm (although he remains a company member of Circus Oz, participating in board appointments at the AGM).

To replace Finch, the board hired Robert Tannion, a Brisbane-born choreographer and dancer who had worked in Europe for 23 years, including as artistic director of Madrid’s Circo de los Horrores. His job was to turn the ship around, artistically and financially.

Folding the Big Top

Tannion, who joined in April 2016, came up with a radical plan to pack away the Big Top and develop smaller shows for niche audiences in smaller venues — a portfolio approach that mitigated financial risk. With two spacious rehearsal rooms, the new building in Collingwood supported the change.

Debate ensued. Could quality be maintained? What were the core values of the company?

“Circus Oz was started by a group of people who were very committed to the circus and the arts,” says Yates. “Financial viability was important, but it wasn’t the be-all and end-all. It was about creativity.”

Tannion led the artistic debate. “There is no one approach,” he says. “It’s about selling confidence in an idea, not in the commercial side. It’s saying, ‘This is a great journey to go on,’ and asking people to come on that journey. Some people will come, while others resist. It is never easy.”

He admitted that at times he “pressure tested” the resistance for validity. “Generosity is the best way forward,” he says. “We all understand that change is fearful.”

The unusual structure of the Circus Oz board — comprising seven members from the wider community, plus two staff members and another two members of five years’ standing — helped smooth the change, says Yates. The performer representatives kept communication between the troupe and its board strong. They contributed to a “mature debate”, he adds. “We went through the fiery furnace of change.”

However, the change was not an instant success. In 2017, total audience numbers fell by more than 13,000 to 65,493. Most of that total came from an international tour in the US and China. In Melbourne, only 23,100 people came to the show. A tour through Queensland and New South Wales netted just 12,700 people.

Yates says it was difficult for the board and the executive. “As a board, you appoint an artistic director — and it is like appointing a managing director. You don’t micromanage them, particularly in an artistic world. I love the arts, but I wouldn’t profess to be a great artistic impresario. We had to back Rob.”

Tannion certainly felt and appreciated the board’s support. “They were always on the end of the phone, no matter how busy they were,” he says. “When I proposed big strategic shifts for the company, they were always met with open arms, discussion and guidance in a supportive way.”

Fortunately, in 2018, audience numbers finally bounced. Some 40,000 Melburnians attended various shows across five different venues. The national tour did not go to Queensland, instead visiting Tasmania and Canberra, more than doubling attendance. The Melba Spiegeltent, now a permanent fixture at the new HQ, doubled its numbers and was voted best venue at the 2018 Melbourne Fringe Festival. In 2018, total audience numbers reached 98,520 — up by more than 50 per cent on the previous year. The tide had turned.

Future focus

So what is next for Circus Oz? On top of its five performances, the company now offers masterclasses, internships, awards, school shows, and school and community access circus workshops. The company is reaching more people in more ways. With increased financial stability, Yates and the board are planning the next three years, and a big surprise for audiences — a possible return of the Big Top in 2020.

“Like anything, we had to lose it to make people want it again,” says Tannion. “The Big Top had become an annual event and people had stopped seeing it. Coming back with a big, cracking show is on the radar.”

Governance lessons for Not-for-Profits

Performer representation on boards

Nicholas Yates, chair of not-for-profit Circus Oz, says the company’s unusual board structure of 11 members is a strength, but comes with challenges. The circus has had performer representatives since its formation.

“That gives us the experience, values and culture side, and a ‘from-the-floor’ viewpoint,” says Yates. “It showed a lot of foresight by the founders of Circus Oz.”

Representatives are given training in their role and responsibilities. Learning about governance gives them insight into the complexities the board grapples with. They can then provide first-hand feedback on issues to the rest of the troupe.

The downside is a large board where the chair’s challenge is to ensure everyone gets a say. Yates says this is a fine balance between allowing vibrant debate and ensuring everyone is heard.

“I find it quite inspiring. The way we are structured gives us a mechanism of getting to the coalface. Sometimes organisations miss that at board level. Easier said than done, though.”

Do the work

Yates says a board is only as good as the members who “get stuck in and make a difference”.

Joint leadership

Artistic director Rob Tannion works closely with Circus Oz general manager Lou Oppenheim. The pair completed Myers-Briggs Type Indicator personality tests when they started working together. “We are polar opposites,” says Tannion. “When I come in with my blue-sky dreaming, Lou asks, ‘How do we fund that?’”

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content