The RBA has released its November Statement on Monetary Policy. The bank has signalled it is prepared to ease monetary policy further if needed and has downgraded consumption and economic growth for the fourth time this year.

The central bank’s new statement is dovish and says that while the Australian economy is coming out of a soft patch, holding the cash rate in November will allow time to assess the effects of past monetary easing and global events. We will look at bank’s new forecasts in more detail next time. In other news, as expected, the RBA left rates unchanged at its 5 November meeting. The Treasurer confirmed that he would make no changes to the RBA’s inflation targeting framework. Retail sales volumes fell in the third quarter as consumption spending remains muted. September saw another big trade surplus as Australian exports continue to ignore the global trade malaise.

What I’ve been following in Australia . . .

What happened:

The RBA left the cash rate unchanged at its 5 November meeting.

The accompanying Statement noted that there had been little change in the economic outlook, with RBA sticking with its message that ‘a gentle turning point appears to have been reached.’ The central bank thinks that the ‘central scenario is for the Australian economy to grow by around 2¼ per cent this year and then for growth gradually to pick up to around three per cent in 2021. The low level of interest rates, recent tax cuts, ongoing spending on infrastructure, the upswing in housing prices in some markets and a brighter outlook for the resources sector should all support growth.’ The key risk remains the outlook for consumption, with the impact of the drought and the future of the housing construction cycle both cited as other important sources of uncertainty.

The RBA thinks that the unemployment rate will remain at current levels ‘for some time, before gradually declining to a little below five per cent in 2021’. The forecast for inflation is that it will pick up ‘only gradually’, with both headline and underlying inflation ‘expected to be close to two per cent in 2020 and 2021.’

In terms of the outlook for the cash rate, the RBA notes that ‘it is reasonable to expect that an extended period of low interest rates will be required in Australia to reach full employment and achieve the inflation target’ and that the Board ‘is prepared to ease monetary policy further if needed.’

Why it matters:

This week’s RBA outcome came as no surprise: none of the 30 economists surveyed by Bloomberg in the run up to meeting had predicted any change, and as highlighted in last week’s note, financial markets had put the probability of a rate cut at less than five per cent

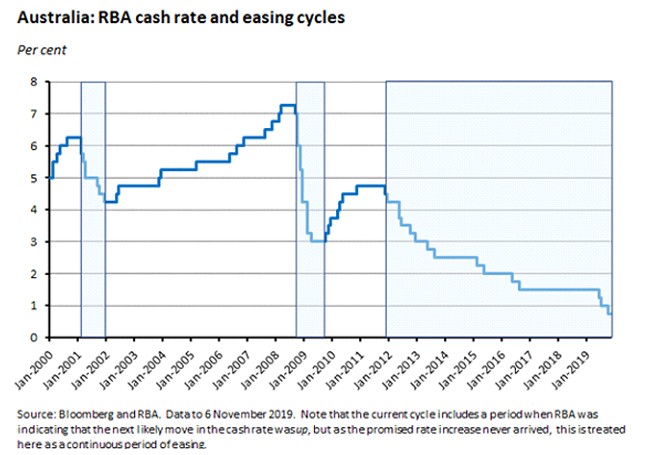

So, is the RBA done? Recent messaging certainly suggests that, after delivering three rate cuts this year, the central bank has shifted into wait and see mode as policymakers want to give lower interest rates and the government’s tax cuts a chance to work through the system before acting again. That shift in emphasis has been picked up in financial market pricing as markets have become much more cautious about predicting any further RBA rate action: at the time of writing the implied probability of a December rate cut was down to less than 19 per cent and the probability of a cut in February next year – still seen as likely by many bank economists – has now eased to around 42 per cent.

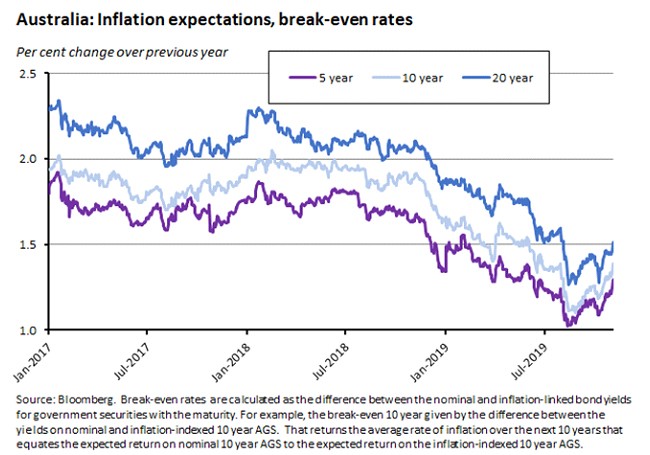

Still, it would be premature to assume that there are no more policy moves to come. We’ll get a more detailed view of the RBA’s expectations with the release of November’s Statement on Monetary Policy this Friday, but according to the forecasts previewed in Tuesday’s Statement, the central bank still thinks that inflation will only be around the bottom of its target band through 2020 and 2021. Reinforcing that inflation forecast, the RBA also thinks that unemployment will only have fallen ‘to a little below five per cent’ in 2021. Remember, its current view is that an unemployment rate of around 4.5 per cent is required to deliver wage results consistent with meeting its inflation target. Absent any additional support from fiscal policy, that suggests that there will be still be pressure for further monetary stimulus. And financial market expectations about future inflation are even more muted: break-even rates suggest inflation expectations are stuck below 1.5 per cent.

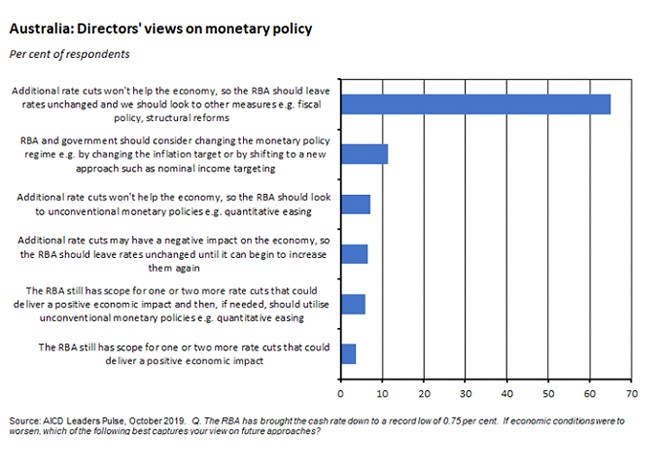

But would additional rate cuts deliver much in the form of stimulus? AICD Directors appear to be sceptical. As argued a couple of weeks back, one reasonably compelling interpretation of the results of our recent Director Sentiment Index (DSI) is that Directors are unconvinced that the RBA’s rate cuts are doing much to boost the economy, and that there was a case for the government using fiscal policy – in the form of infrastructure spending or perhaps by bringing forward planned income tax cuts – to boost growth. 1

When we sought to test that interpretation of the DSI by making use of the AICD Leaders’ Pulse survey, we found that of those Directors responding to the survey, there was a clear majority in broad agreement with the proposition that further rate cuts would do little for the economy, and that a better option – assuming more stimulus were to be needed – would be to rely on fiscal policy and / or structural reforms.2

Interestingly, the second most popular option selected by our respondents was to consider making changes to the monetary policy regime. That’s not on the agenda for now (see the next story) but given the current environment does seem likely to return as a future option.

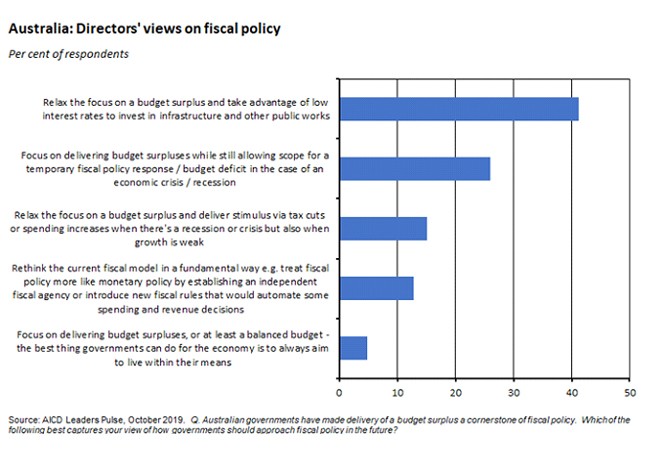

In the case of fiscal policy, opinions were more divided, with no outright majority for any of the policy options available to our survey respondents. Still, the most popular option from the menu on offer was that of relaxing the current focus on attaining a budget surplus and taking advantage of low interest rates to boost public investment in infrastructure.

Taken together, then, our two Pulse results do provide some indicative support for our previous interpretation of the DSI results as supporting a shift from monetary to fiscal support for the economy.

What happened:

The Treasurer announced that he would make no changes to the current Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy. The Statement sets outs the common understanding of the Government and the Governor of the RBA on Australia’s monetary policy framework. Typically, changes to the Statement have coincided with either a change of government or the appointment of a new central bank governor, with the last Statement issued in September 2016 with the appointment of Governor Lowe. In his announcement, Treasurer Frydenberg said that he had ‘concluded that the existing statement is consistent with the Government’s and the RBA’s shared understanding of our monetary policy framework. Not changing the statement provides continuity and consistency at this time of global economic uncertainty.’

Elaborating on his reasoning in a little more detail in a piece for the AFR, the Treasurer noted that although recent years had seen inflation stuck below the bottom of the RBA’s target band, low inflation was now common across much of the developed world, with inflation running at less than two per cent in three-quarters of the world's advanced economies, and below one per cent in one-third of the same group. He also judged that ‘over the medium term, inflation is expected to return to the band consistent with the statement.’

Why it matters:

Last week’s piece noted that with inflation once again below target, there would inevitably be questions over the parameters of the current inflation targeting regime. And while there was certainly no expectation of any major change to the current framework at this point, there had been some suggestion that Frydenberg might seek to make a more modest adjustment in the form of amending the current framework to require the RBA governor to write a formal letter to the Treasurer explaining why the bank had missed its target, in line with Bank of England practice.

In the event, the Treasurer has decided to leave things as they were, in effect buying Lowe’s argument that the current arrangements already offer sufficient flexibility to the central bank, judging that the case for change is still outweighed by the benefits of leaving the current system in place and the associated ‘stability and predictability’. Again, not surprising in the current context. It seems unlikely that this will be the final word on this debate, however, with arguments over how monetary policy should adapt to the current environment still gathering pace across the world economy.

What happened:

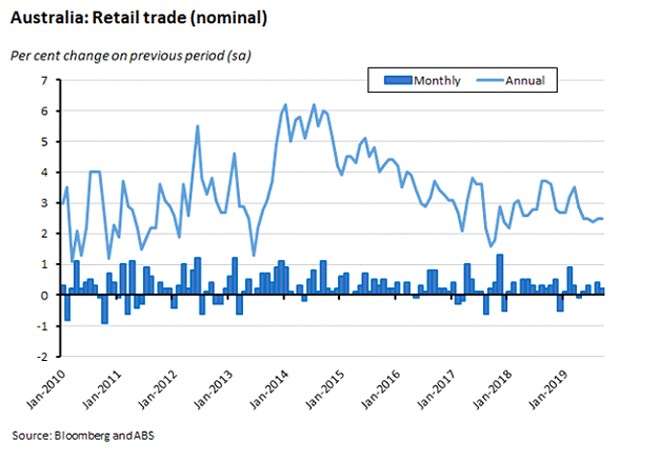

According to the ABS, retail turnover in September rose by 0.2 per cent over the previous month (seasonally adjusted), down from the 0.4 per cent pace recorded in August. In annual terms, turnover grew at 2.5 per cent, unchanged from the previous month.

By state, there were increase in retail turnover in Western Australia (0.7 per cent), New South Wales (0.3 per cent), Tasmania (one per cent), South Australia (0.2 per cent), the Australian Capital Territory (0.1 per cent) and the Northern Territory (0.1 per cent). Turnover was flat in Victoria and fell in Queensland (down 0.1 per cent).

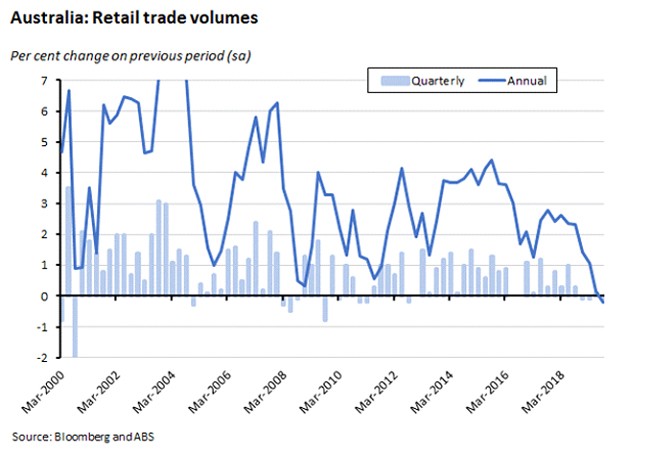

The ABS also released data on volumes for the September quarter. These showed turnover declining by 0.1 per cent over the quarter, following a 0.1 per cent rise in the June quarter and a 0.1 per cent fall in the September quarter. In annual terms, volumes fell by 0.2 per cent.

Why it matters:

The monthly turnover figures for September were softer than market expectations for a 0.4 per cent monthly increase, rounding off what has been a disappointing third quarter for retail spending. That was also reflected in the quarterly data on volumes, where the negative annual result in the September quarter of this year brought the first year-on-year fall in retail trade volumes since the June quarter of 1991.

The RBA has repeatedly flagged weakness in the household sector – showing up as sluggish consumption spending – as a key downside risk to its forecasts for the Australian economy. The plan / hope has been that tax cuts and lower interest rates will support for household incomes which would then feed through into higher spending. But for now, the data suggest that the stimulus is yet to deliver; there is little sign here of the RBA’s ‘gentle turning point’.

What happened:

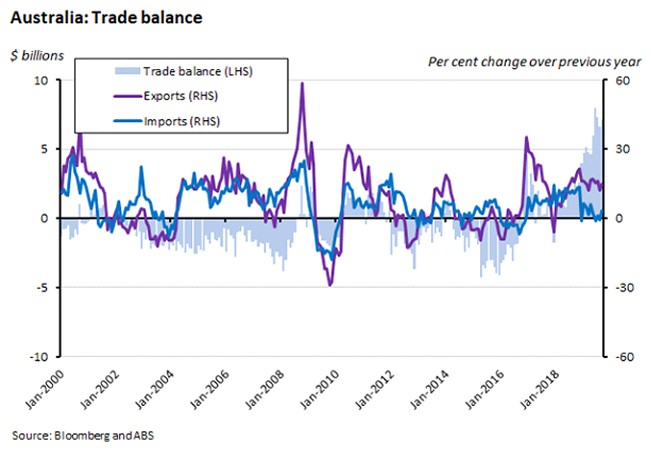

ABS data show that Australia recorded an impressive $7.2 billion trade surplus (seasonally adjusted) in September, an increase of $563 million on August’s upwardly revised $6.6 billion surplus.

The sum of seasonally adjusted trade surplus for the September quarter is $21.1 billion which is up from the already-large $18.6 billion surplus recorded in the second quarter of this year. Note, however, that the ABS calculates that if the same seasonal factors used in compiling the quarterly balance of payments are used, then the preliminary Q3 2019 surplus falls slightly to $20.9 billion, up from a Q2 2019 surplus of $19.3 billion.

Exports of goods and services rose by three per cent over the month of September, with increases in the export of non-rural goods (up two per cent, driven by exports of other mineral fuels which rose by eight per cent and metal ores and minerals which grew by three per cent), non-monetary gold rose (which jumped by 26 per cent) and rural goods (up a healthy six per cent).

Imports of goods and services also increased by three per cent over the month, with capital goods imports up 12 per cent, intermediate and other goods up four per cent and imports of consumption goods up just one per cent.

Why it matters:

September’s result was significantly better than market expectations of a $5.1 billion surplus and likely puts the economy on track to record a second consecutive current account surplus in the September quarter: to recycle an old joke, you wait forever (well, 44 years) for a current account surplus to come along, and then you get another one right after.

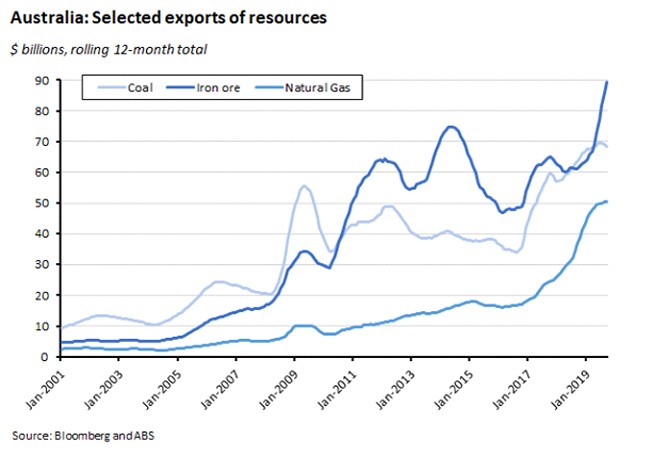

The result also shows that Australia’s export performance has proved to be extremely resilient in the face of the global trade malaise. While newspaper headlines declare that the world’s largest exporting economies are suffering from the slowdown in global trade and rise in protectionism, Australia’s monthly export values have been soaring. One key distinguishing factor here is that while global manufacturing has been struggling, with sectors from electronics to autos suffering, Australia has been benefiting from a surge in the value of iron ore exports and a longer-running increase in LNG volumes.

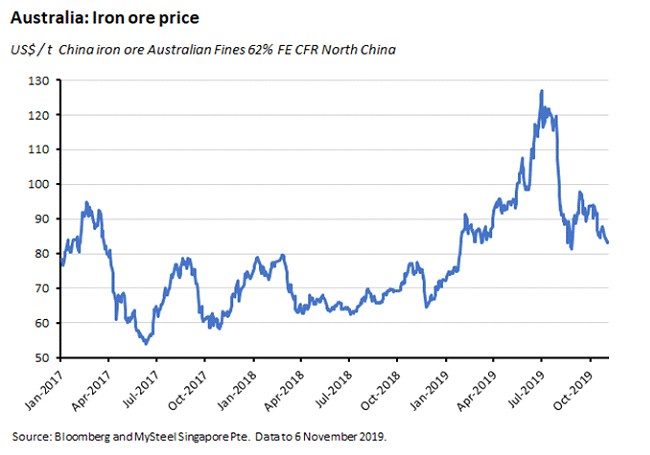

As is well known by now, a large part of the iron ore story has been about price and here September’s trade result was boosted by a partial unwind of the sharp price decline that took place over August this year.

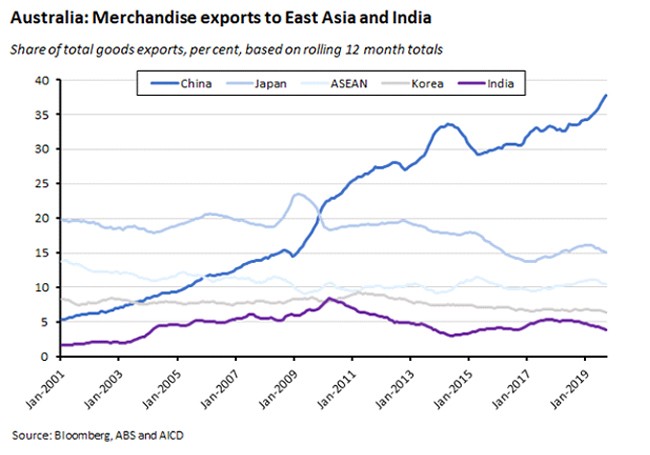

The trade story is also about the continued importance of Chinese demand: in the year to September, for example, China was the destination for about 82 per cent of all Australian iron ore exports. There’s been a sustained rise in the share of all Australian merchandise exports heading to the Chinese market, with that share having jumped by more than four percentage points over the year to date.

There’s a bit of irony3 here, of course. Just at the time when Australia has been debating its potential economic vulnerability to China in the context of enhanced geo-economic competition between Beijing and Washington (see for example last week’s readings), our export exposure to that same market has been climbing to new highs. The reality to date is that theoretical concerns about economic dependency are yet to be manifested in any kind of diversification strategy as the successful exploitation of the concrete gains comparative advantage continues to comfortably trump any perceived strategic angst.

What happened:

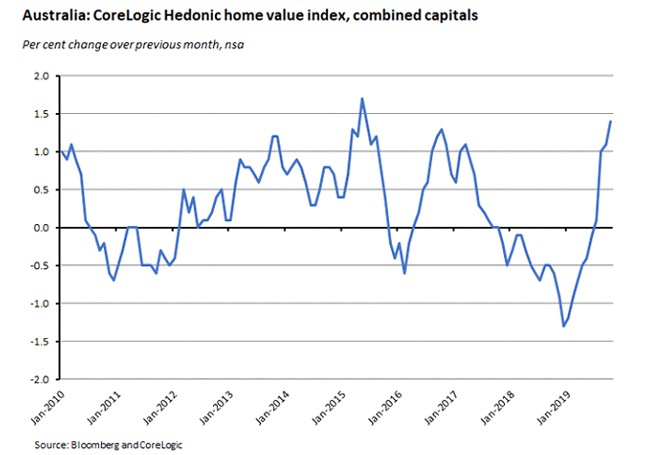

Last Friday, CoreLogic reported that Australian dwelling values across the combined capital cities rose by 1.4 per cent over October, with national values up 1.2 per cent. That leaves values for the combined capitals roughly seven per cent down from their peak.

Although growth was once again driven largely by Melbourne (dwelling values up 2.3 per cent over the month) and Sydney (up 1.7 per cent), values increased over October in every capital city apart from Perth. According to CoreLogic, over the three months ending in October 38 of 46 capital city sub-regions have recorded a rise in dwelling values, indicating the relative breadth of the current recovery.

Why it matters:

The housing market recovery continues to sustain momentum with four consecutive months of positive price moves for the combined capitals series and three consecutive months of monthly growth running at one per cent or more. Indeed, October’s pace of increase was the (joint) fastest recorded since May 2015. With Australian mortgage rates now at their lowest levels since the 1950s, monetary policy looks to be having a strong effect on house prices, even if its impact elsewhere in the economy has so far been relatively muted. The RBA will be hoping that this unwinding of the negative wealth effect that has served as a headwind for households will start to allow monetary policy to secure greater traction in boosting private consumption. If it were to be sustained in the longer term, however, this pattern of an asymmetric response of the economy to low rates will become a policy concern.

. . . and what I’ve been following in the global economy

What happened:

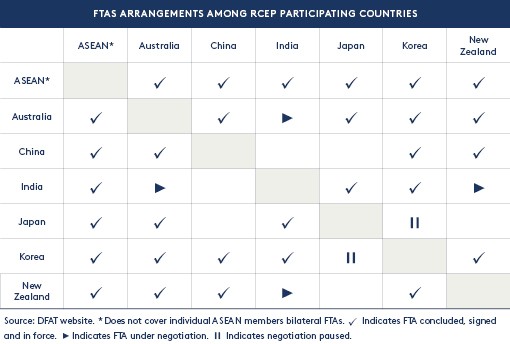

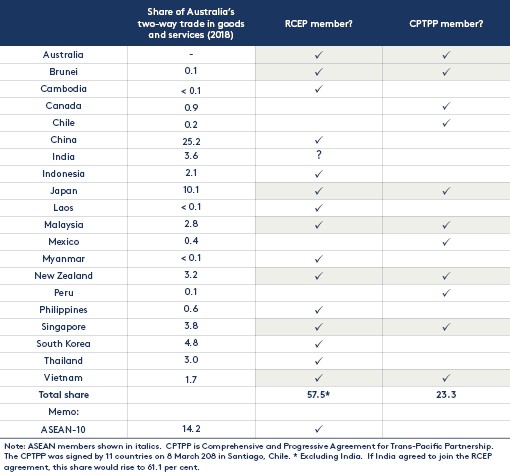

Australia and 14 other countries agreed to finalise the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), with the aim of signing the deal next year. The 15 of the 16 RCEP countries that have accepted the current negotiations include nine of Australia’s top 15 trading partners, which together comprise about 58 per cent of our trade and two thirds of our exports.

The RCEP process was launched in November 2012 and negotiations commenced the following year. They brought together 16 Indo-Pacific countries to negotiate a regional free trade agreement (FTA), with the potential membership comprising Australia, Brunei, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Lao, Malaysia, Myanmar, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. All of those economies, bar India, have now agreed to the deal, with the Joint Leaders’ Statement (pdf) noting that ‘15 RCEP Participating Countries have concluded text-based negotiations for all 20 chapters and essentially all their market access issues’ and were targeting signing the deal in 2020. The statement goes on to note that ‘India has significant outstanding issues, which remain unresolved. All RCEP Participating Countries will work together to resolve these outstanding issues in a mutually satisfactory way. India’s final decision will depend on satisfactory resolution of these issues.’

Why it matters:

Sceptics have tended to dismiss RCEP as a ‘wide but shallow’ agreement, arguing that in order to succeed in getting all the diverse potential membership on board, the FTA had to be watered down in a ‘lowest common denominator’ sort of way. Even then, that compromise apparently proved insufficient to woo India, with Delhi reportedly worried about the vulnerability of its agricultural, textile and dairy sectors and concerned that signing up would see India’s already sizeable bilateral trade deficit with China widen even further4. RCEP has also been described somewhat dismissively as ‘the stapler’, in that it mainly serves to staple together a range of existing bilateral and regional agreements, rather than deliver new, additional liberalisation.

While there may be some merit in these criticisms, however, they also underplay the importance of the agreement. RCEP delivers several important results.

First, consider ‘the stapler’. What this means in practice is that RCEP offers an overarching framework that encompasses a range of existing bilateral and regional trade agreements by establishing a common set of regional trade and investment rules. The latter includes one set of rules of origin and one standard set of documentation required to claim lower tariffs on goods exported. This ‘stapler’ effect should work to mitigate the so-called ‘spaghetti bowl’ (or in a regional context, ‘noodle bowl’) problem that can arise if membership in a range of disparate FTAs ends up boosting transactions costs for businesses by leaving them facing a complex and potentially inconsistent array of variable tariffs, complicated rules of origin and bureaucratic red tape.

Second, consider the global context. Here, the deal is symbolically important, coming as it does against the backdrop of a range of trade conflicts (including between co-signatories Japan and Korea) and protectionist pressures. The East Asian region has been a key beneficiary of export-led growth and a relatively open global economy, and the RCEP deal sends a useful signal that many regional economies continue to see the benefits of international economic integration.

Third, and related, RCEP is also a call-back to the old idea that trade and economic integration can be a positive force for geopolitical stability. By seeking to bind together regional economies in a closer network of commercial exchange, RCEP has at least the potential to deliver non-economic benefits to the region.

Fourth, from an Australian perspective, RCEP membership offers a valuable complement to membership in the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). In its original manifestation as the plain old Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), it was widely seen as a US-led attempt to create an alternative economic architecture to balance against what Washington feared would otherwise become an increasingly China-centric regional trading order. In that context, simultaneous membership in both the TPP and RCEP offered a means to keep Australia plugged into both versions of the regional future, keeping our options open. With the withdrawal of the United States from the TPP and its transformation into the CPTPP the option value of that balancing act has shifted somewhat, but joint membership in both arrangements – something Australia shares with other key regional economies like Japan and Singapore – keeps Australia involved in two approaches to the regional trading game.

Unfortunately, the absence of India from the agreement, while not surprising given the noises coming from Delhi over the course of the negotiations, is disappointing and does lower the likely economic and strategic pay offs from RCEP. It also, perhaps, tells us something about the appetite for, and constraints facing, India’s economic reform efforts despite Delhi’s need to boost what has been a flagging growth story this year. Still, remains scope for India to join in the future and thereby extend RCEP’s reach into South Asia.

What I’ve been reading: articles and essays

The RBA’s November chart pack is now available.

According to HSBC, Australian businesses are relatively sanguine about global trade wars, with about two-thirds of those surveyed by the bank saying they thought they would gain more than they lost from the current environment.

ANZ bluenotes reckons that the shift towards a low-carbon economy is changing the mix of Australia’s mining commodities, with large forecast increases in long-term demand for lithium, cobalt, nickel, alumina, manganese and vanadium, despite some near-term price weakness due to a supply overhang.

Two alternative views on RCEP. Peter Drysdale and Adam Triggs in the AFR make the case for – ‘In a world that is splintering, RCEP offers a beacon of hope’. Mike Bird in the WSJ instead sees ‘a paper tiger in the making’.

Benedikt Frey and Ebrahim Rahbari look at the lessons from the British Industrial revolution for the resistance to automation and propose a range of policy options they think could cushion the disruptive impact of technological change.

Related, this piece in the NYT from a few weeks ago looks at a predicted White-Collar Job Apocalypse that has (so far?) failed to materialise. A much-cited 2007 study (pdf) by Alan Blinder estimated that ‘somewhere between 22 per cent and 29 per cent of all US jobs are or will be potentially offshorable within a decade or two’ (although do note that Blinder made no estimate of how many jobs would actually be offshored). It turns out that the labour savings potentially on offer from moving to lower-wage emerging markets have been offset by a range of other factors including time differences, language barriers, legal hurdles, and the challenges involved in coordinating work over distance. A follow up paper published this year finds that ‘instead of being offshored, the types of work predicted to be at risk of offshoring are increasingly being performed remotely by workers within the United States’. It seems that while technology did enable jobs to be done remotely, that instead meant working from home, or shifting to another, lower cost US location, rather than relocating work overseas.

Drawing on recent work by the IMF, Martin Wolf sketches out an approach to climate policy that seeks to steer a path between Trump and Thunberg: his preference involves a ‘pragmatic resort to all policy tools, including market-based incentives; use of the revenue raised from carbon pricing to compensate losers and make the tax system and climate mitigation more efficient; a stress on the local environment benefits of eliminating the use of fossil fuels; and, above all, a commitment to climate as a shared global challenge.’

The Economist reviews Branko Milanovic’s Capitalism, Alone. You can hear Milanovic talk about his new book here. (I haven’t read this latest effort, but can recommend one of his earlier books, Global Inequality.)

Also from the Economist, why it’s possible to fool some of the people all of the time.

The latest edition of the Journal of Economic Perspectives is available online. Timothy Taylor (the managing editor) provides a useful summary of the contents here. It includes another symposium on populism (I linked to a VoxEu debate on populism last week). The piece on ‘Informational Autocrats’ looks interesting but maybe the plethora of analysis now appearing on this topic suggests we are approaching ‘peak populism’? George Akerlof’s essay on how macroeconomics became divorced from financial stability issues might be worth a look too: it gets a nice plug from FT Alphaville.

Greg Ip on the implications of the Trump tax cuts. Ip wonders if the ‘ho-hum’ results of the tax package for growth and investment will provide fuel for more radical approaches to US fiscal policy in the future.

Bloomberg Businessweek has an interesting piece that attempts to gauge how the world’s economies are posed to deal with disruption. The good news is that on their metrics, Australia looks in pretty good shape.

From the same source: The global fertility crash.

1 At the time of the DSI, the RBA had delivered two rate cuts with a third cut widely expected (and duly delivered in October).

2 Note that these results can be treated as indicative only, as (1) the sample size for the Leaders’ Pulse is much smaller than for the DSI and (2) the sample for the Pulse is not designed to replicate the DSI sample.

3 No pun intended!

4 Indian negotiators were also reportedly unhappy with the level of market access on offer for their services and pharmaceutical sectors.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content