From ESG to shareholder activism, here are the 9 equity market trends that could impact how your board governs.

Canadian governance expert Professor David Beatty suggests in this age of shareholder activism boards might lead their organisation’s investor relations function and allocate up to a third of their time to investor engagement. Given such a workload, boards of large listed companies would have to spread their investor relations effort across more directors.

The chair of the remuneration committee typically leads a board’s investor engagement, but it’s hard to see how they can remain the only contact when an increasing number of investors here and overseas expect deeper engagement with boards on a wide range of issues. El-Ansary says it is inevitable some companies will rethink the glare of public markets with compliance and regulatory demands.

We outline several powerful trends changing share ownership of Australian listed companies.

- Rise of the Passive Investor

Few investment trends are more powerful than the growth in passive investing. Exchange traded funds (ETF) are described as “passive” because they aim to match the price and yield performance of an underlying benchmark index, unlike “active” funds, which aim to beat the index return. Most, but not all, ETFs are index funds. Not all index funds are ETFs.

Australasian Investor Relations Association (AIRA) CEO Ian Matheson FAICD says growth in passive investment on share registers has crept up on boards. He includes high-frequency trading funds (which use computer-based trading models) in this category because these funds, while they are active investors, also demonstrate a passive governance approach.

Matheson notes growth in passive investing has been the biggest trend in investor relations in Australia in the past five years.

“ASX-listed companies, large and small, are seeing passive investors emerge on their share register or increase their shareholding,” he says. “From an engagement perspective, boards have lagged on this issue and collectively underestimated the influence of index funds.”

- Big Super

- Environment, Social and Governance Focus

- Short Sellers

- Globalisation

- Sovereign Wealth Funds

He says Australian boards must increasingly engage with large index funds. “For the most part, index funds are pretty sensible on governance and want to meet with boards. I suspect companies have struggled to reach out to index funds because they are not used to dealing with them on governance matters, or don’t know them in the same way they know active fund managers.”

The global ETF market is projected to reach US$7.6 trillion by 2020 and exceed the actively managed funds market by 2027, according to EY’s Global ETF Research survey. The survey notes that lower fees — and a recognition that index funds deliver higher returns, after fees, on average than actively managed funds — are driving ETF growth and giving issuers greater ownership and influence over listed companies. Australia’s ETF sector is just a minnow in comparison to the global industry, with the value of ASX-quoted ETFs climbing to $51b in July 2019.

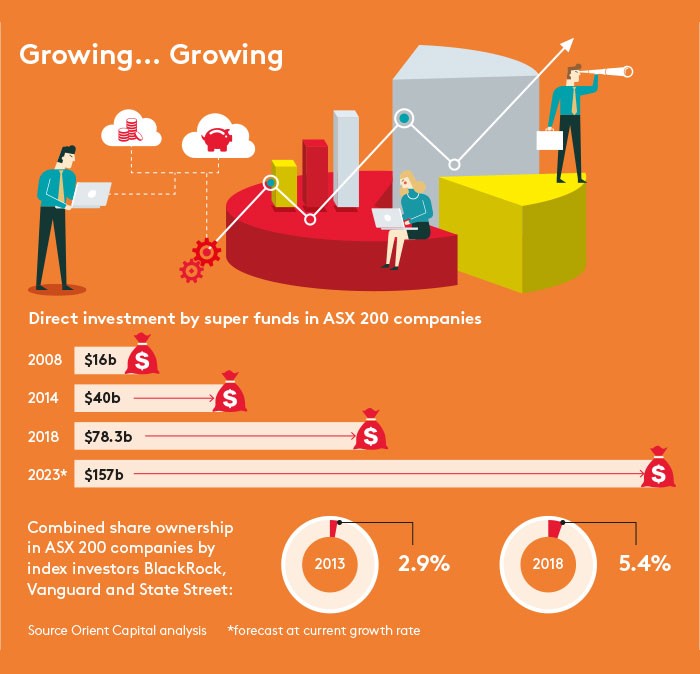

According to research by Orient Capital, a leading global provider of share analytics and market intelligence, the combined share ownership in ASX 200 companies by BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street has increased from 2.9 per cent to 5.4 per cent over five years. The data, compiled for Company Director, shows these three index providers are a top-20 shareholder in many ASX-listed companies.

“The share ownership of passive investors in Australia is quickly rising off a low base,” says Lysa McKenna, CEO of Link Group Corporate Markets, Asia Pacific. “This style of investor, which includes index funds, ETFs and quant [quantitative] funds, will become a bigger consideration for boards because of their interest in governance and due to the fact they increasingly have the voting power to influence board change.”

According to the CORPNET research group at the University of Amsterdam, the three largest ETF issuers — BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street — have nearly US$11 trillion in assets under management, including active funds, which is more than all the world’s sovereign wealth funds combined. These three ETF issuers are believed to be the largest shareholders in 40 per cent of all US listed companies.

Globally, BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street have become vocal proponents of governance change. In BlackRock’s 2018 proxy voting guidelines, the company called on the boards of companies in which it invests to have at least two female directors. In his most recent annual letter to CEOs, chair Larry Fink called on organisations to better balance social purpose and profit.

ETF governance influence can be limited. Whether a company has good or bad governance, an ETF issuer has to hold it to replicate the index in which it sits. Unlike active fund managers, ETFs have to hold stocks in their index, regardless of performance. There is also a view that ETF issuers mostly outsource ESG analysis to proxy advisors.

However, in almost 80 institutional proxy voting campaigns from 2018 reviewed by Orient Capital, passive investors followed proxy advisor voting guidelines 62 per cent of the time. When proxy advisors voted against a board recommendation, passive investors followed the recommendation only 23 per cent of the time.

“Our research shows these styles of investors are anything but passive on shareholder voting,” says McKenna. “They are doing their own analysis, engaging directly with boards on ESG issues and building up their internal teams of ESG analysts.”

ASX 300 boards need to understand the proxy voting guidelines of ETF issuers and ensure their organisation remains in the index. “If an index fund is a substantial shareholder, the organisation needs to stay in that index,” adds McKenna. “If it drops out, the fund has to sell its stock.”

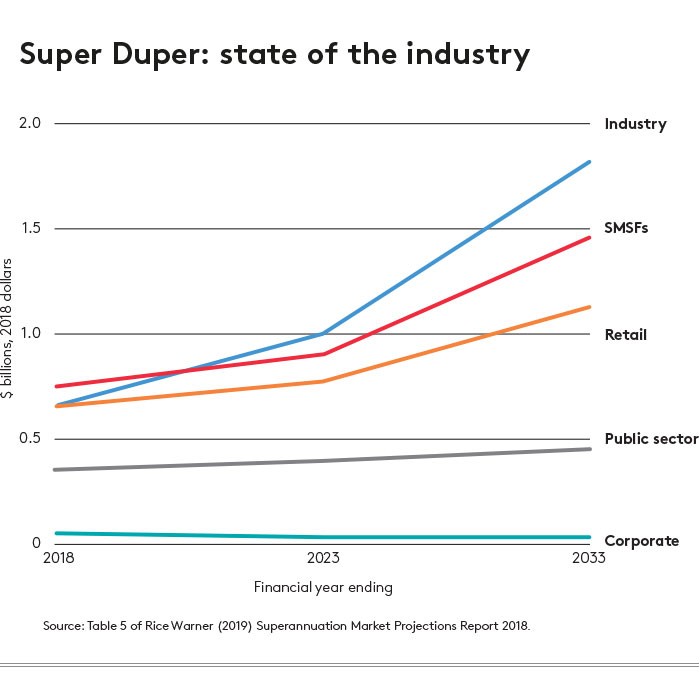

According to Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) data, industry super funds had $677b in assets under management as of March 2019. As a super category, industry funds are second to self-managed superannuation funds ($746b) and the gap is closing.

Direct super fund investments in ASX 200 companies have more than doubled to $78.3b in the past five years, according to Orient Capital analysis. In 2008, that figure was $16b. If the growth rate continues, direct investment by super funds in ASX 200 companies is estimated to reach $157b by 2023.

“Industry super has a vast pool of capital to invest and it’s likely this will grow faster in the next few years as more funds move from retail super funds to industry funds,” says McKenna. “Boards will have to engage with super funds on investor relations matters, particularly as they internalise more of their investment functions and as their voting power grows.”

The fallout from the banking Royal Commission is also driving growth in industry super funds. The Commission exposed conflicts, high fees and poor ethical behaviour in some retail super funds owned by big banks or investment firms. In the year to March 2019, for-profit retail super funds recorded a net cash flow of $16.4b in members’ funds.

“The Royal Commission found a lot more governance conflict in retail super funds than in industry funds,” says Australian Council of Superannuation Investors (ACSI) CEO Louise Davidson AM MAICD. “We would expect more investors to favour industry funds after the Royal Commission highlighted so many problems in the banking sector.”

Sector consolidation is adding to the influence of industry super funds. Fee pressure and the need to find greater economies of scale are encouraging these funds to join forces. Additionally, a regulatory push by APRA and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) is encouraging underperforming super funds to close or find the right partners.

In July, First State Super and VicSuper said they were progressing plans to create Australia’s second largest profit-to-member super fund, managing $120b in assets for more than 1.1 million members, moving to due diligence with the aim of a merger by June 2020. It would see the combined group closer in size to AustralianSuper, the nation’s largest super fund, which manages $165b of members’ assets.

In May 2019, Catholic Super and Equip Super announced a $26b merger that will catapult the combined entity into the ranks of Australia’s 10 largest super funds. This followed on the heels of the merger of Sunsuper with AustSafe Super to create a fund with $64b in assets under management.

To save money as industry funds expand, investment functions are being internalised rather than outsourced to fund managers. AustralianSuper, for example, managed 31 per cent of its portfolio internally in FY18, according to its latest annual report, and says it is on track to manage up to half of its assets internally by 2021.

These trends point to a reduced number of industry super funds in the next five to 10 years. They will be larger, have greater voting power, significant internal analysis on ESG issues and will demand deep engagement with boards. AustralianSuper, for example, expects to double its assets to $300b by 2025.

As industry super funds grow, their interest in ESG and non-financial performance metrics is likely to firm. Responsible investing has emerged as a key investor relations task and boards are engaging more often with investors on ESG-related issues

Davidson expects industry funds to be more active in the governance debate in the coming decade. In April 2019, ACSI called for annual director elections, non-binding shareholder resolutions, a binding vote on remuneration policies every three years and disclosure on the ratio of a CEO pay to median Australian workers.

“As industry funds grow, there will be more community pressure on them to use their influence to ensure good governance and corporate behaviour in line with community expectations,” says Davidson. “That’s entirely appropriate. Members should scrutinise their superannuation fund’s capability to be a responsible long-term steward of their capital. This trend is not going away. Fund members want to know their capital is invested in companies that do the right thing, companies that are well-governed and able to deliver long-term, sustainable value. They want to use their investment power to drive positive change in business and society, to ensure the best possible investment.”

Along with the move by large super funds to bypass fund managers and internalise more of their investment portfolio to cut fees and gain greater control, they are increasingly active on sustainability issues. Large funds are also expanding their ESG research capabilities and forming more of their own voting recommendations rather than outsourcing it to proxy advisors. Boards must engage with beneficial owners rather than intermediaries.

In May 2019, 17.5 per cent of shares in poultry producer Inghams Group were held as short positions, according to the ASIC short positions report table. In May 2019, almost 16 per cent of JB Hi-Fi Limited was held by short positions, which bet on a falling share price. Boards of ASX 200 companies and beyond are increasingly having to monitor short sellers as some have destabilised companies by releasing damaging research reports on the stock.

Offshore investors hold almost one third of the market capital of ASX 200 companies, according to Orient Capital’s 2018 Understanding Ownership Trends in Australia report. This means increased offshore investor roadshows and engagement for chairs of large listed companies as they meet international shareholders.

US investors held 15 per cent of ASX 200 market capital in 2018 — the largest share outside Australia. US ownership of Australian companies has doubled during the past five years, mostly due to growth in US index funds. The big three — BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street — account for 90 per cent of the North American position, reinforcing their growing influence in this market.

Norges Bank, which invests on behalf of the Government Pension Fund of Norway, and the Government Pension Investment Fund of Japan, continues to increase its ownership of ASX 200 companies. Although Norges Bank — with its investments in high-profile companies such as BHP and Santos — was particularly vocal about governance issues such as board diversity and fossil-fuel investments, it has recently modified its position regarding the ESG compliance of companies such as Rio Tinto. As of 31 December 2018, the bank had $19.37b invested in Australian equities. The influence of Chinese sovereign funds is another issue for boards, particularly in the resource sector.

- Shareholder Activism

- Growing Private Equity Pool

- High-frequency trading

Activist investors are shareholders at publicly traded companies who attempt to affect change in an organisation either by directly appealing to, or putting heavy pressure on, the board, bypassing the normal advisory process. More than US$200b was invested in activist funds in 2016, up from US$47b in 2010, according to a report by Activist Insight.

Canadian governance expert David Beatty says every Fortune 500 company in the US now has at least one activist fund running the rule over it. The upshot is an increasing number of US hedge funds joining share registers of ASX 200 companies. They will be pushing for change, either on their own or as part of a pack of institutional investors.

In Australia, shareholder activism is less advanced, but the number of domestic activist campaigns is at unprecedented levels, according to a Gilbert + Tobin study. Activists have targeted ASX-listed companies with increasingly sophisticated public campaigns. Separately, they have pressured on ESG issues, with seven of the ASX 50 having an ESG-related shareholder resolution put forward at their AGM — although, so far, each has failed.

Private equity is on the rise as more capital flows into unlisted companies and influences their governance. US private equity investment rose eight per cent to US$331b in 2018, according to research from the American Investment Council. That figure has doubled since 2010 as US pension funds increase their allocation to alternative investments.

This has resulted in more listed companies in Australia and abroad being taken over by private equity firms — either on their own or as part of a consortium with superannuation funds — and privatised. This trend has been underscored by private equity bids for MYOB, Healthscope, education provider Navitas and pet care group Greencross in the past year.

Australian Investment Council analysis shows assets under management by private equity and venture capital fund managers based in Australia have been rising at an increasing rate since 2016, to a record $30b in June 2018. There is also $11.4b in “dry powder” — capital that has been raised, but not yet invested. AIC’s Al-Ensary says more large institutional investors, family offices and high net worth investors are looking to allocate a larger portion of their funds in the private market.

Investors are turning to unlisted assets and strategies including private capital because they are among the best-performing assets in recent times (see table). For example, as of March, Australia’s sovereign wealth fund Future Fund had 15.4 per cent of its $154b assets allocated to private equity.

This form of short-term trading, where software algorithms automate buy-and-sell decisions, is estimated to account for a quarter of total ASX share turnover, according to 2018 ASIC report High-frequency trading in Australian equities and the Australian-US dollar cross rate.

High-frequency traders can be highly active in a company’s share turnover; they account for 45 per cent of all Australian equities orders, says ASIC. But these investors are passive from a governance perspective because they do not vote on shareholder resolutions. For boards, that means a high proportion of share turnover — and day-to-day ownership — is from computer programs with no governance interest.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content