Welcome back to the Weekly Note, which returns after a month-long holiday. This week we catch up on the latest inflation numbers, review last week’s RBA minutes and labour market report, consider the latest IMF forecasts for the world economy and provide an update on progress with RBA reforms and the appointment of a new central bank governor. Plus, the usual linkage roundup.

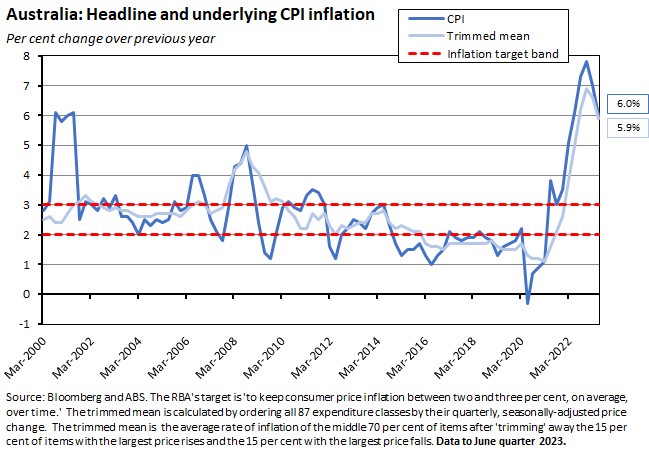

The week’s big economic news was the June quarter 2023 inflation reading. It showed the headline rate of annual consumer price inflation dropping to 6 per cent, down from 7 per cent in the March quarter. The underlying rate of inflation also fell, easing to 5.9 per cent from 6.6 per cent. Both results came in below market forecasts and below the RBA projections set out in the May 2023 Statement on Monetary Policy, indicating that the pace of disinflation is currently running a bit ahead of expectations. It wasn’t all good news on the inflation front, however: the ABS also reported that the annual rate of services inflation had risen to 6.3 per cent, the highest recorded since 2001 and the introduction of the GST.

With the RBA Board meeting on 1 August, attention has focused on implications of the inflation numbers for next Tuesday's policy decision. According to the minutes of the 5 July Board meeting, the CPI data are one of three key releases that are expected to inform the monetary policy debate, along with this Friday’s retail sales and last week’s labour force. The retail figures arrive too late for our publication deadline, but we do have the other two inputs. Unhelpfully, they point in different directions. Labour market statistics not only saw employment growth comfortably outpace market expectations, but also put the unemployment rate down at just 3.5 per cent. That would argue for another rate increase. But the inflation report – setting that services number aside – is instead consistent with a policy pause.

With the RBA in data-driven mode, market assessments of the likely direction for policy are now shifting after each major release. For example, on 19 July, the day before the publication of the labour force data, market pricing was consistent with a 25 per cent probability of a 25bp rate hike at the August meeting. But by close of business on 20 July, the strong employment results had pushed that probability up to 43 per cent. The inflation numbers have had a similar but opposite effect this week. At close of business on 25 July – the day before the CPI release – financial markets were still pricing in a 41 per cent chance that the RBA would lift the cash rate target to 4.35 per cent next Tuesday. But by close of business on the day of the release, that probability had fallen to just 14 per cent. It’s possible that Friday’s retail trade numbers will see the odds change again.

Where does that leave us? Once again, we think that the RBA’s rate decision is set to be a close call, even if market pricing at the time of writing reckons that another pause is by far the more probable decision. Either way, there is a growing consensus that – barring another bout of inflationary shocks – the RBA is approaching the end of the tightening cycle. There may be one or perhaps two more 25bp hikes still to come, depending on the data flow, but it is noticeable that the debate is already beginning to shift from ‘where will the cash rate peak?’ to ‘how long will the RBA leave rates at current levels before it starts to ease again?’ Interestingly, the US monetary policy debate appears to have reached a similar point, albeit after 525bp of rate hikes as opposed to the RBA’s 400bp. As usual, more detail follows below.

This week on The Dismal Science podcast, we ask if Australia has won the war on inflation and whether the US is headed for a soft landing.

Inflation in Q2:2023 was lower than expected

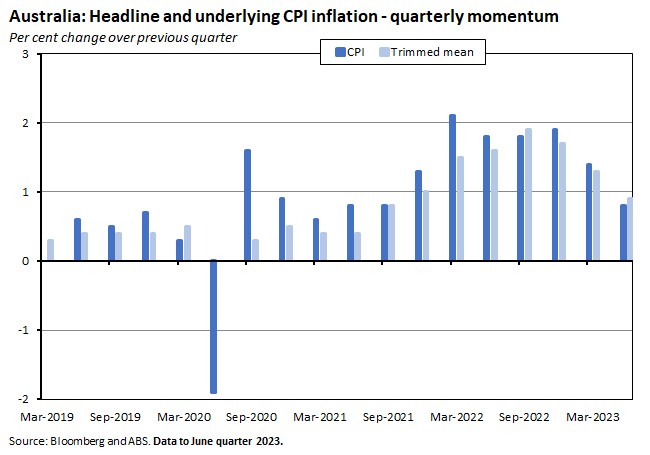

The ABS said Australia’s quarterly consumer price index (CPI) rose 0.8 per cent over the June quarter 2023 to be up six per cent over the year. That was well down from the March quarter’s 1.4 per cent quarterly and seven per cent annual rates. It was also lower than economists had expected, with the market consensus having predicted one per cent quarter-on-quarter and 6.2 per cent year-on-year rates. Underlying inflation, as measured by the trimmed mean, at 0.9 per cent over the quarter and 5.9 per cent over the year was similarly down from the March print of 1.3 per cent quarter-on-quarter and 6.6 per cent year-on-year and was likewise a little softer than the consensus forecast for rates of 1.1 per cent and six per cent, respectively.

The annual rate of headline CPI increase in the second quarter of this year was the smallest since the March quarter of 2022.

In terms of inflationary momentum, on a quarter-on-quarter basis price growth has eased on both a headline and trimmed mean basis, in each case dropping down to below a one per cent quarterly rate and less than four per cent at an annualised rate. The quarterly headline rate was pulled lower in Q2 by price falls for domestic holiday travel and accommodation (down 7.2 per cent), electricity (down 1.8 per cent) clothing accessories (down 2.2 per cent) and automotive fuel (down 0.7 per cent). As a result, the rate of quarterly inflation in June was the lowest since Q3:2021.

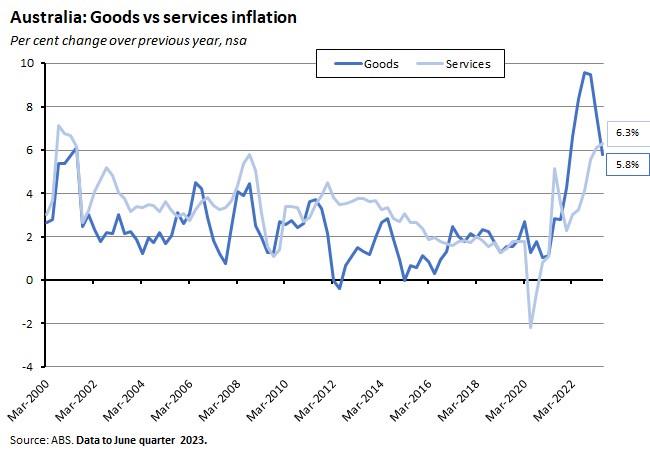

A key feature of this week’s data was the diverging pattern of goods and services inflation. The overall drop in the headline rate of annual CPI inflation reflected another decline in the annual rate of goods inflation, which after peaking at 9.6 per cent in the September quarter 2022 has now fallen for three consecutive quarters, most recently dropping to a rate of 5.8 per cent in the June quarter 2023 from 7.6 per cent in March.

That slowdown has been driven by several factors, including continued decline in the rate of growth in new dwelling prices (down from a Q3:2022 peak of 20.7 per cent to 7.8 per cent in Q2:2023), a modest easing in food price inflation (down from a peak of 9.2 per cent in the December quarter 2022 to 7.5 per cent in the June quarter of this year) and smaller rates of increase for furniture, household appliances and clothing. Moreover, automotive fuel prices fell 3.6 per cent over the year.

In contrast, the annual rate of services inflation rose from 6.1 per cent in the March quarter to 6.3 per cent in the June quarter, producing the strongest result since 2001 and the introduction of the GST. According to the ABS, services inflation is broad-based, with marked increases for rents (up 6.7 per cent over the year in their largest rise since 2009), utilities (up 13.8 per cent year-on-year), insurance premiums (up 14.2 per cent) and domestic holiday travel and accommodation (up 13.9 per cent).

The headline rate of annual CPI inflation has now fallen 1.8 percentage points from its recent peak of 7.8 per cent in the December quarter of last year. The rate of decline in underlying inflation has been more modest – a drop of one percentage point from a peak of 6.9 per cent in Q4:2022 – but is still significant. Moreover, both the headline and underlying inflation rates are falling somewhat faster than the RBA had anticipated. In the forecasts presented in the May 2023 Statement on Monetary Policy, the central bank reckoned headline inflation would be 6.3 per cent in the June quarter, while underlying inflation was projected at six per cent.

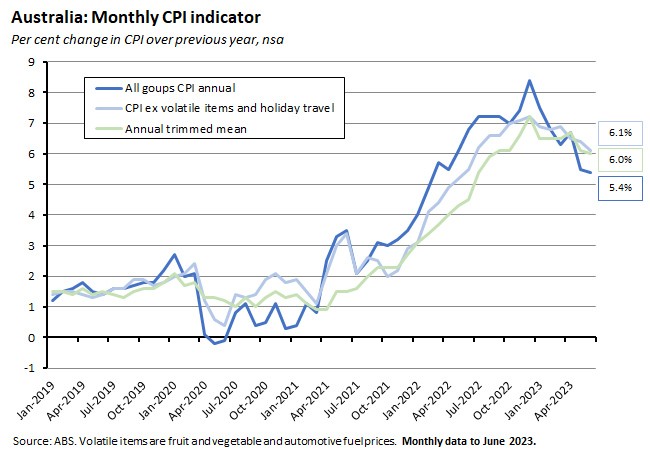

The ABS also published the monthly CPI indicator for June 2023 which rose 5.4 per cent over the year. That was down from a revised 5.5 per cent print in May 2023 and in line with market expectations. The annual rate of increase for the monthly version of the trimmed mean eased from 6.1 per cent in May to six per cent in June, while the year-on-year increase in the CPI excluding volatile items and holiday travel slowed from 6.4 per cent to 6.1 per cent over the same period.

Monetary policy and the message from the RBA’s July 2023 minutes

At its 4 July Board meeting, the RBA Board decided to leave the cash rate target unchanged at 4.1 per cent, with the accompanying statement noting that the ‘decision to hold interest rates steady this month provides the Board with more time to assess the state of the economy and the economic outlook and associated risks.’ Last Tuesday, publication of the minutes from that meeting confirmed that the Board had debated between a 25bp increase and a pause. According to the minutes, the case for a hike had rested on six observations:

- Inflation was forecast to remain above target for an extended period and in the absence of further tightening, the duration of this deviation from target could be even longer;

- Rent and services prices more generally were showing signs of high and persistent (sticky) inflation;

- Likewise, electricity prices had risen strongly on 1 July and this could have larger effects on future inflation outcomes than currently anticipated;

- The current period of weak productivity performance was leading to strong growth in unit labour costs;

- This effect could be exacerbated by a still-tight labour market (see below for the latest numbers) that seemed likely to contribute to above-average increases in wages and prices in the future; and

- The policy rate in Australia was still lower than in many comparable countries (elsewhere, RBA Governor Lowe has explained this difference in policy settings as reflecting relatively lower rates of nominal wage growth in Australia plus a more flexible local labour supply response, as well as the RBA’s deliberate decision to try to preserve as much as possible of the COVID-era labour market gains).

On the other hand, the case for leaving policy settings unchanged rested on five offsetting factors:

- The RBA had already delivered 400bp of policy tightening over a relatively short time frame and as a result, ‘the stance of monetary policy was clearly restrictive at the prevailing cash rate’;

- Moreover, since monetary policy operates with a lag, the full effects of that 400bp of past tightening were still to hit;

- Meanwhile, mortgage payments as a share of household disposable income had reached a record high as of May this year and were set to rise further, even absent of any additional changes to the policy rate (as existing fixed rate deals expired);

- There was considerable uncertainty about the likely resilience of household consumption in the face of current rate hikes and if consumer spending slowed by more than expected, the unemployment rate could rise ‘beyond the rate required to ensure inflation returns to target in a reasonable timeframe’; and

- Inflation was now declining both in Australia and across advanced economies more generally (with the latter reflecting the healing of global supply chains and lower commodity prices), and this would help mitigate the risk of any rise in medium-term inflation expectations.

In addition, the minutes noted that by the time of next month’s meeting, the Board ‘would have the benefit of additional data on inflation, the global economy, the labour market and household spending, as well as an updated set of staff forecasts and a revised assessment of the risks.’

The Australian labour market remains tight

Of the three Australian data points listed in the RBA minutes, the inflation numbers arrived this Wednesday as discussed above. The labour market data was released last week, when the ABS published labour force data for June 2023. A fall of 11,000 in the number of unemployed people saw the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate remain at 3.5 per cent, unchanged from a downwardly revised May result, and beating market expectations for a 3.6 per cent print. The underemployment rate was also unchanged at 6.4 per cent, while the underutilisation rate fell to 9.9 per cent in June from 10 per cent in May.

Employment growth surprised to the upside last month, with employment rising by about 32,600 in June, which was considerably stronger than the market consensus for a 15,000 gain. As a result, the employment to population ratio remained at its record high of 64.5 per cent and while the participation rate eased to 66.8 per cent, that was only slightly down from May’s record high of 66.9 per cent (and the female participation rate rose to a record high of 62.6 per cent). Monthly hours worked rose 0.3 per cent over the month, slightly outpacing the 0.2 per cent rise in employment.

The incoming RBA Governor combines continuity with change

The RBA has more than inflation on its mind. It is also in the midst of significant institutional change. On 14 July, the Treasurer announced that he was appointing Michele Bullock as the ninth Governor of the RBA for a seven-year term that will begin on 18 September this year. Bullock is currently RBA Deputy Governor and has been at the central bank since 1985. By choosing a senior RBA insider with a long bank career, the Treasurer has opted for what in many respects is a continuity candidate. At the same time, there are obvious and significant elements of change. For a start, the Treasurer opted not to extend the contract of the incumbent governor – something that had been afforded to both of his predecessors this century. Second, this was an appointment for the history books, with the RBA getting its first female governor in its 63-year history. Finally, until her appointment as Deputy Governor in April 2022, Bullock was not formally part of the RBA’s monetary policy decision-making process, with most of her career focus having related to the ‘financial plumbing’ aspects of the RBA’s mandate – the financial and payments systems. So, she was not directly associated with the two periods of monetary policy that have been subject to significant criticism - the post-GFC period when the RBA is accused of having kept policy too tight for too long, and the post-COVID period where the charge is that policy was too easy for too long.

What are the implications of this appointment for the current stance of RBA policy? They appear to be modest. As noted, Bullock has been Deputy Governor since last April, and therefore has been part of the monetary policy decision making process for the whole of the current tightening cycle that began in May 2022. Yes, post-September it will be worth confirming that the new governor remains in full agreement with the current approach of being prepared to allow inflation to return to target in a relatively gradual manner in order to limit any increase in unemployment. In this context, her 20 June speech on achieving full employment would indicate that she is on board, with the speech saying, ‘A faster return [of inflation] to target would likely mean more job losses in the short term. Our judgement is that if we can return inflation to target in a reasonable timeframe – while preserving as many of the employment gains as we can – that would be a better outcome.’

A progress update on RBA reform

A key task for the incoming governor in September – along with returning inflation to target – will be to implement the recommendations of the recent Review into the RBA. The initial shape of that response was set out by the current governor in a speech on 12 July this year. Key changes related to the implementation of monetary policy include:

- The RBA will reduce the number of meetings of the Board to set monetary policy to eight times a year from the current 11.

- The length of those Board meetings will be extended, so that they will now typically start on the Monday afternoon and continuing to the Tuesday morning, with the outcome announced at 2.30pm on the second day.

- The post-meeting statement announcing the Board’s decision will be issued by the Board instead of the Governor. The Governor will also hold a media conference after each Board meeting to explain the outcome.

- All Board members will be able to attend an internal staff meeting some time before the Board meeting to allow them to hear a broader range of staff opinion. The Board will also oversee the Bank’s research agenda as it relates to monetary policy and aspects of financial stability.

In addition, Governor Lowe said the Board will work with Treasury to undertake five-yearly reviews of the monetary policy framework.

Lowe then went on to note that while the Review had made a range of other policy-related recommendations, the current Board had decided it would be better to consider these once the required legislation had been passed and the new Monetary Policy Board had been established. These include recommendations relating to the publication of an unattributed vote, regular public appearances for all Board members, the establishment of an expert advisory group, and the publication of board papers with a five-year lag. Lowe’s the speech also discussed proposed changes to the management of the RBA.

The IMF is sounding a bit more positive

Finally, the July 2023 IMF World Economic Outlook Update was published this week. After a run of gloomy reports, this one sounded somewhat more positive. Granted, the Fund still says that the world economic recovery is slowing, with global growth forecast to fall from 3.5 per cent last year to three per cent this year and next. That leaves activity running below the 3.8 per cent average growth rate recorded between 2000 and 2019. But that 2023 growth projection represents a modest 0.2 percentage point upgrade to the Fund’s April 2023 forecast for growth this year. The improvement in the near-term outlook reflects a resilient service sector performance in the first quarter of this year, along with the successful intervention by authorities to contain fallout from turbulence in the US and Swiss banking sectors (and a consequent easing in global financial conditions) and the more recent resolution of the US debt ceiling standoff.

In more good news, the Fund also thinks inflation will come down slightly faster than it did back in in April, with global inflation now forecast to fall from 8.7 per cent in 2022 to 6.8 per cent in 2023 and 5.2 per cent in 2024. The 2023 projection is 0.2 percentage points lower than the previous forecast, although the 2024 projection is 0.3 percentage points higher. By way of comparison, in the years before the pandemic (2017-19), global inflation was running at around 3.5 per cent. The IMF cautioned that the decline in core inflation was likely to be more gradual than progress in lowering the headline rate, with underlying inflation now forecast to slow from an average of 6.5 per cent in 2022 to six per cent this year and 4.7 per cent next year.

While the Fund now thinks that ‘the global economy is headed in the right direction’, it also thinks that ‘it is too early to celebrate’ as the balance of risks remains tilted to the downside. Or, using the words of the IMF’s Chief Economic Counsellor and Head of Research, the global economy is on track but not yet out of the woods.

Other things to note . . .

- From the Parliamentary Budget Office, Beyond the budget 2023-24: Fiscal outlook and sustainability.

- Two reports from the Productivity Commission: the Trade and Assistance Review 2021-22 which includes interesting discussions on the persistence of ‘temporary’ COVID19 support measures, how climate policy might act as a form of industry assistance and the resilience of Australian exports in the face of Chinese pressure; and the latest Productivity Bulletin which examines the recent decline in productivity growth.

- Related, Michelle Grattan on the appointment of Chris Barrett as new chair of the Productivity Commission.

- ABC Business warns that China’s economic woes are bad news for Australia.

- The AFR’s Michael Read considers the balance of voting power on what will be the RBA’s new Monetary Policy Board. Unusually, external members will have a majority (seven out of nine) of votes.

- Hawkins and Schirmer review Treasury’s new wellbeing framework. For background, here’s the July 2023 Measuring what Matters Statement.

- The IMF’s Gita Gopinath on three uncomfortable truths for monetary policy, recent Fund research on the relative contributions of import Prices, profits and wages to Eurozone inflation, and an IMF note examining the political economy of GovTech.

- The WSJ is gloomy on Europe.

- Also from the WSJ, Greg Ip reckons Bidenomics is missing the economics of industry policy.

- Related, the Economist is sceptical of the current rush to industry policy. But Noah Smith reckons much of this criticism is missing the point.

- A re-evaluation of the 2010 China-Japan rare earths dispute reckons this is a case of narrative triumphing over facts, but also cautions that appearing to have weaponised trade may have similar consequences to actually doing so.

- The Economist magazine analyses China-India relations, pointing to growing economic ties as a potential precursor to a more positive bilateral relationship.

- Interesting piece on the growing importance of algorithms in setting prices.

- Along with coverage of recent labour market developments, the OECD Employment Outlook 2023 includes a review of the potential employment implications of artificial intelligence. Australia country notes.

- Also from the OECD, Government at a Glance 2023 and the OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2023-2032.

- AON provides an overview of global economic losses due to catastrophes during the first half of this year. Full report here.

- World Bank blog on the impact of high temperatures on workers and the global economy.

- An FT Big Read on Macquarie Bank and infrastructure. (During my recent visit to the UK, one notable economics theme was the sense that some key aspects of the UK’s big privatisation program of the 1980s and 1990s had failed, with water cited as a key example.)

- William Davies in the LRB on the changing political economy in the UK. While the economy might appear to be reliving the 1970s, Davies argues there are no signs that the solution will look like Thatcherism – instead a ‘national security’ state might offer one potential replacement for the outgoing neoliberal consensus.

- The world China is building.

- Branko Milanovic with 11 theses on globalisation.

- A new McKinsey Global Institute Report analysing how the pandemic is changing real estate markets in the world’s superstar cities, as office attendance has stabilised at 30 per cent below pre-COVID norms.

- Reading about the Mongol Storm.

- Podcast version of a ‘long read’ on the Saudi Century.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content