The domestic economic news this week was split between two major developments. On Tuesday, the Treasurer delivered the first Federal Budget of the new government and then on Wednesday the ABS published data on the September Quarter 2022 Consumer Price Index (CPI) along with the latest monthly CPI figures.

My initial take on the budget was in a separate email to members, along with some additional thoughts that were posted to the AICD’s website. But from a macroeconomic perspective, the key point is that the Treasurer’s relative fiscal restraint means that Budget 2022-23 – The Sequel does not complicate the RBA’s inflation-fighting task in the near term.

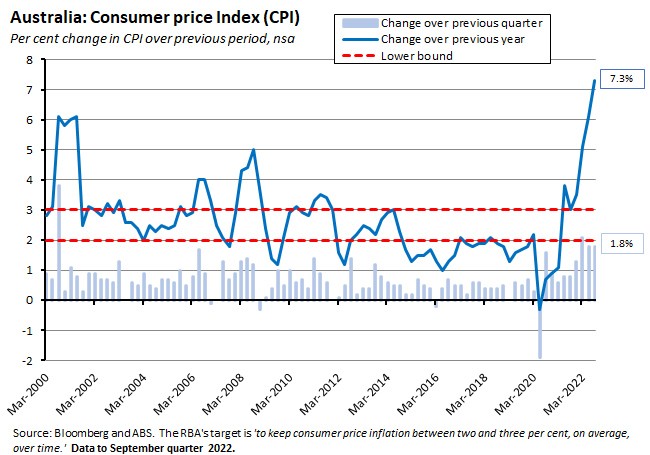

This abridged version of the regular weekly note mainly covers the latest inflation data. The surge in the annual headline rate in Q3:2022 to 7.3 per cent delivered the highest year-on-year rate in more than three decades. That result locks in another RBA rate increase next week while re-opening the debate on the relative merits of further 25bp vs 50bp policy moves. There’s also a quick look at the Flash PMI result (pdf) for October, which reported the first contraction in private sector activity since January this year. But no linkage roundup this time – Budget week has left me with little time to do any extra reading.

Next Thursday (3 November), our last economics webinar for 2022 will cover some of the key themes from the past year – the resurgence of inflation, the return of negative supply shocks, the fallibility of central banks, the weaponisation of economic interdependence, and the transformation of the labour market, as well as this week's attempt by the Treasurer to start a conversation on Australia's fiscal challenges – and I will also talk about what all that might mean for the year ahead and beyond.

Inflation surprises to the upside in Q3:2022

The ABS reported that the CPI rose 1.8 per cent quarter-on-quarter in Q3:2022 to be up 7.3 per cent in year-on-year terms. That’s the highest annual rate recorded since the June quarter 1990, when the headline rate was 7.7 per cent. The pace of quarterly increase was unchanged from the June 2022 quarter and a bit below the March 2022 quarter’s 2.1 per cent jump, but otherwise was the highest recorded this century with the sole exception of the September quarter 2000 spike associated with the introduction of the GST.

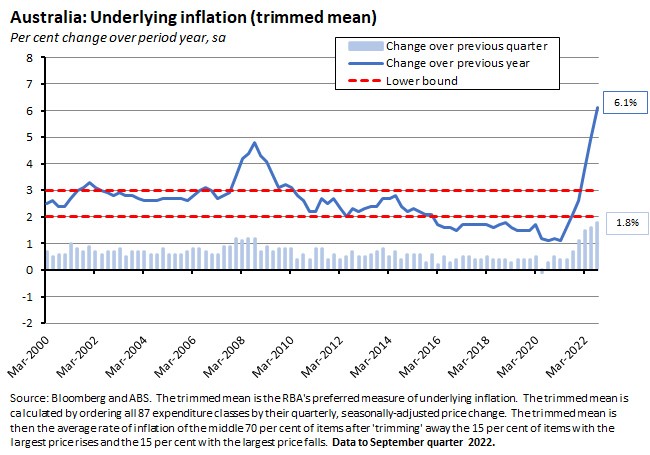

Underlying inflation, as captured by the trimmed mean measure, also increased by a record 1.8 per cent in quarterly terms and surged to 6.1 per cent on a year-on-year basis.

Markets had anticipated a high third quarter inflation result, but September’s outcome still managed to surprise to the upside, particularly with regard to underlying inflation: the consensus forecast for the headline CPI print had been for 1.6 per cent quarter-on-quarter and 7.1 per cent year-on-year increases while for the trimmed mean the median expectation was for 1.5 per cent quarterly and 5.5 per cent annual rates.

In line with the September quarterly CPI, the monthly CPI indicator rose 7.3 per cent in the year to September, following annual rises of 6.9 per cent in August and 7.0 per cent in July.

New dwellings, gas, furniture drive this quarter’s inflation outcome

In quarterly terms, prices rose across eight of the 11 groups that make up the CPI, with price pressures strongest for housing (up 3.2 per cent), food and non-alcoholic beverages (also up 3.2 per cent), and furnishings, household equipment and services (up 2.8 per cent).

- In the case of the housing group, new dwelling purchases were a key contributor, rising 3.7 per cent over the quarter. The ABS pointed to increased costs for labour, materials and freight as driving the price growth, although the pace of increase was down from the March (5.7 per cent) and June (5.6 per cent) quarters, reflecting a degree of easing in supply constraints as well as a softening in housing demand.

- A second key contributor from the housing group was utilities (up 4.8 per cent over the quarter). The big movement here came from gas and other household fuels, which surged by 10.9 per cent in the largest rise seen since 2012 as the impact of annual gas price reviews resulted in higher wholesale prices being passed on to consumers. Electricity prices were also up 3.2 per cent, although here the pace of increase was moderated by rebates introduced by the Western Australian, Queensland and ACT governments. Importantly, in the absence of these government interventions, the ABS estimates that electricity prices would otherwise have jumped by 15.6 per cent last quarter.

- Sticking with the housing group, the ABS also highlighted a marked increase in the rate of rental price growth in Sydney and Melbourne, with a third consecutive quarterly increase in Q3 producing the strongest quarterly rise in ten years for both cities. With rents already climbing strongly in other cities, rents overall rose 1.3 per cent this quarter, their largest increase since 2011.

- In the food and non-alcoholic beverages group, the Bureau pointed to increases in meals and takeaways due to higher ingredient, wage and transportation costs, along with higher prices for fruit and vegetables arising from high input costs and weather-damaged crops.

- Finally, in the Furnishing and household equipment group, furniture rose 6.6 per cent due to continued supply chain issues including higher costs for freight and raw materials.

Note that September’s quarterly increase would have been even larger, but for an offsetting decline in automotive fuel which fell in all three months to be down a significant 4.3 per cent over Q3 due to lower oil prices. The restoration of the fuel excise to 46 cents per litre (up from 22 cents per litre) which took effect on 30 September will, however, contribute to higher fuel prices in the December quarter this year.

In annual terms, the key drivers of the increase in the CPI in Q3 were new dwellings (up 20.7 per cent) and automotive fuel (up 18 per cent but down from the dramatic 35 per cent rate recorded in the March quarter). The rate of increase for new dwellings was the fastest annual growth on record, although the Bureau did note that part of this reflected fewer grant payments from Federal and State governments relative to the same quarter last year: strip that effect out, and the rate of annual increase would ease slightly to 17.7 per cent.

Goods, services, traded, non-traded, essentials, discretionary inflation

Three other features of the September quarter inflation report are worth noting:

- The annual rate of goods inflation (9.6 per cent, the highest since 1983) continues to run ahead of the rate of inflation for services (4.1 per cent). According to the ABS, goods accounted for a bit more than three quarters of the annual increase in the headline CPI last quarter. That is symptomatic of the ongoing importance of high freight costs, supply constraints and the shift in the composition of household expenditure as drivers of inflationary pressures.

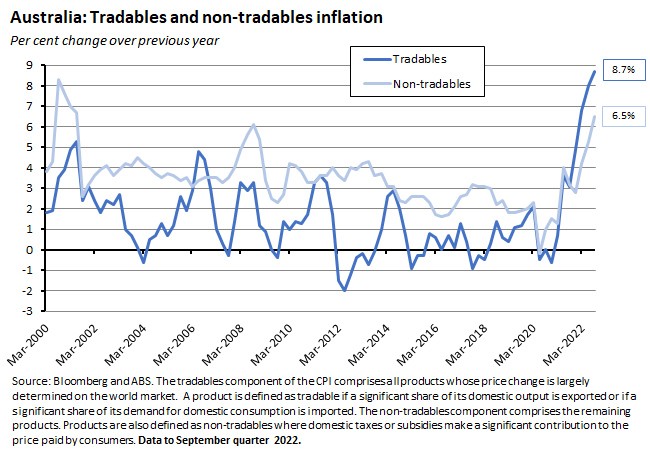

- Likewise, the annual rate of traded inflation (8.7 per cent) remains greater than the rate of non-traded inflation (6.5 per cent). Still, the sustained increase in the latter reflects the current significance of domestic factors in the inflation story in addition to those disruptions (supply chains, commodity prices) afflicting the international environment.

- The annual rate of increase for essential (technically, non-discretionary) goods and services is still faster than that for non-discretionary items: 8.4 per cent vs 5.5 per cent. It’s the rise in the cost of essentials that is the key factor imposing painful cost-of-living pressures on households.

This quarter’s inflation report keeps the pressure on interest rates and the RBA

If there was any doubt that the RBA would hike the target cash rate again at November’s meeting (and there probably shouldn’t have been), this week’s inflation report will have dispelled it. Martin Place will set to tighten policy again. What the higher than expected inflation outcomes for Q3 do add, is that they raise questions over the central bank’s decision to surprise markets and slow the pace of rate increases to 25bp at the 4 October monetary policy meeting and – more importantly – over whether the RBA should opt for a 50bp move next week. In particular, the case for a retreat next month and a return to a more aggressive tightening strategy would rest on two arguments.

- First, that the ongoing rise in the headline inflation rate will be destabilising for inflationary expectations (or for inflation psychology, to use Governor Lowe’s preferred terminology), and that things here are likely to get worse before they get better. According to Treasury’s budget forecasts, for example, electricity prices are expected to rise by an average of 20 per cent late this year and by a further 30 per cent in 2023-24, while retail gas prices are also projected to rise, helping to push inflation up to 7.75 per cent by the end of this year. The restoration of the fuel excise will also boost the headline rate. That’s in line with the RBA’s own forecasts as presented in the August Statement on Monetary Policy (SOMP), which also see a December quarter rate of 7.75 per cent. A return to aggressive rates would provide a countervailing force.

- And second, the rapid rise in underlying inflation in Q3 indicates that inflationary pressures may be more entrenched than the central bank expected - those same RBA forecasts only projected the annual rate of underlying inflation to hit six per cent by the December quarter of this year. (Note that the RBA forecasts will be updated with the publication of the next SOMP on 4 November.)

The arguments against reverting to a 50bp hike are largely those rehearsed in the minutes to the 4 October meeting that explained Martin Place’s decision to go with a 25bp hike earlier this month – that is, a combination of higher economic uncertainty both overseas and at home, the lagged impact of policy tightening, and the additional flexibility afforded by the relative frequency of RBA policy meetings.

Given that the RBA has already considered and accepted those arguments, it seems unlikely that it would want to change course so quickly. Indeed, such a rapid reversal could arguably be more damaging for credibility and therefore inflation psychology than any positive signalling message from a more aggressive move. So, on balance, another 25bp remains the most likely outcome on 1 November. That said, recent meetings have shown the RBA is prepared to surprise the markets and RBA-watchers alike, so a 50bp move can’t be completely ruled out.

One last point relating to the RBA and inflation. In recent notes, we’ve discussed the relationship between a weaker Australian dollar, inflation and monetary policy. RBA Assistant Governor Christopher Kent gave a speech on Monday this week on Exchange Rates and Inflationary Pressures. Kent noted that while the Australian dollar has fallen by 14 per cent against the greenback this year, it has only depreciated by two per cent in trade-weighted terms over the same period. Since the central bank’s modelling suggests it is the trade-weighted index that is the more important driver of imported inflation, Kent reckoned that the impact of currency moves to date will be relatively modest, reporting that ‘a rough rule of thumb from our models suggests that the level of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) will be higher by only around 0.2 per cent in total over the course of a few years.’

This week on The Dismal Science podcast, we look at Australia's surging inflation numbers and what they could mean for the upcoming RBA meeting. Plus: Key points from this week's budget and the delayed release of China's GDP data. And what do pizza toppings tell us about India's GST system?

What else happened on the Australian data front this week?

The S&P Global Flash Australia Composite PMI (pdf) fell to a nine-month low of 49.6 in October 2022, down from an index reading of 50.9 in September. The Flash Services PMI also fell to a nine-month low of 49. The Flash Manufacturing Output Index (which at 53 slipped to a two-month low of 53) and the Flash Manufacturing PMI (which fell to a 14-month low of 53.5) also both dropped this month, although they remained in expansionary territory.

October’s result marks the first time that the Composite PMI has fallen into negative territory since January this year, indicating that activity in Australia’s private sector has suffered its first contraction in nine months, dragged down by a downturn in the services sector.

According to S&P, the result mainly reflected a decline in demand for services, due to tighter monetary policy and elevated prices, with survey respondents citing higher interest rates and increased market uncertainty. At the same time, the PMI’s measure of overall business confidence also fell this month, dropping to its lowest reading since the peak of the pandemic in April 2020. The combination of RBA policy action, ongoing capacity constraints, and a deteriorating global environment is now taking a toll business activity.

While services are suffering, the story is different for manufacturing. Despite a monthly fall, the manufacturing PMI is still in expansionary territory, recording its 29th consecutive month of expansion in October, supported by ongoing growth in new orders.

Finally, the PMI results also reported that input and output costs both continued to rise this month, with respondents citing higher costs for fuel, wages and raw materials. The pace of output inflation rose relative to September, although there was a moderation in the rate of input price inflation.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content