More signs of recovery in the Australian housing market this week. But business and consumer sentiment both sank again, suggesting the monetary and fiscal stimulus we’ve seen to date is getting only limited traction in the wider economy. Meanwhile, after a tough August, global markets appear to have rediscovered some optimism in September.

This week’s readings cover additional testimony on monetary policy from the RBA, new research from the Department of Industry, the case for a progressive consumption tax, economists at war and Northern England’s ‘murdered towns.’

What I’ve been following in Australia . . .

What happened:

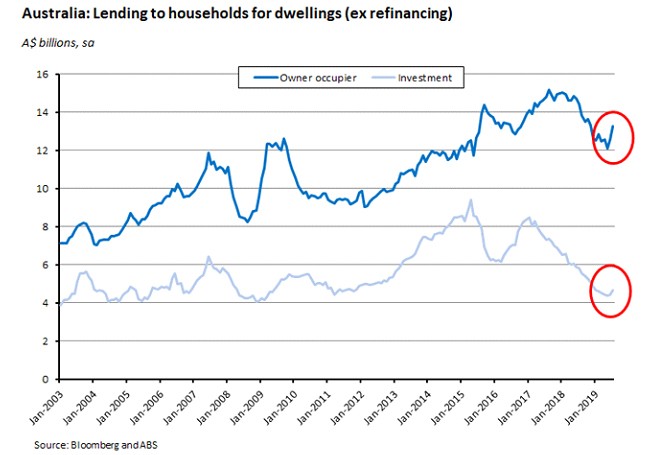

According to the ABS, new lending to households increased by 3.9 per cent in July over the previous month (seasonally adjusted). Strikingly, for a second consecutive month there were strong increases in the level of new lending commitments to owner occupiers (up 5.3 per cent over the month) and to investors (up 4.7 per cent), although both results were still well down on July 2018, by 8.3 per cent and 20.4 per cent respectively.

There were also increases in the number of new lending commitments to owner occupier first home buyers (up 1.3 per cent) and owner occupier non-first home buyers (up four per cent).

Why it matters:

Last week we noted that a monthly jump in house prices in Sydney and Melbourne had prompted speculation that the housing market may have shifted from stabilisation to recovery mode. This week’s bounce in lending numbers adds a bit more fuel to that narrative, and to the parallel story about what has so far been the diverging impact of monetary policy on the economy – good news for asset (house) prices, less so for business and consumer confidence.

What happened:

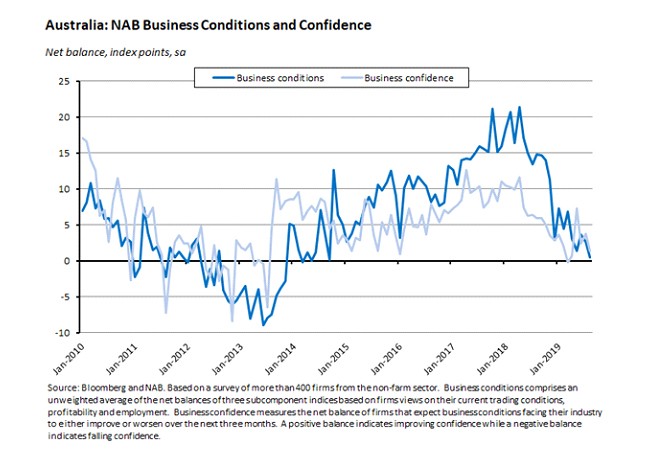

The NAB monthly business survey showed both business confidence and business conditions fell in August. At +1 index point, both are now well below their long-run averages.

The reading on business conditions was pulled down by falls in the trading and profitability sub-indices, although the employment sub-index increased. By sector, transport & utilities, finance, business & property services, and mining drove the monthly decline, offset by a rise in retail, although despite the increase, the latter remains deep in negative territory.

Why it matters:

According to NAB, this month’s results indicate that momentum in the Australian business sector continues to weaken, suggesting that any recovery in private demand after a soft first half of the year is yet to materialise. The day after the survey result was released, NAB economists changed their forecast for the RBA’s cash rate, predicting that a 25bp cut in November will now be followed by another 25bp cut in February.

What happened:

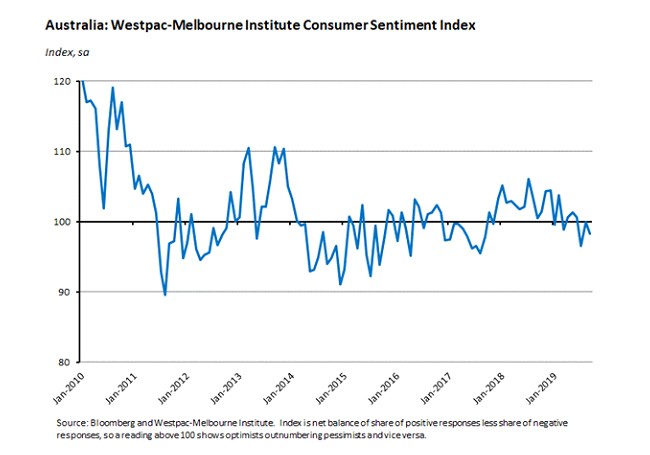

The Westpac-Melbourne Institute Index of Consumer Sentiment (pdf) fell to 98.2 in September from 100 in August, returning the index to negative territory.

Respondents’ views on the state of family finances and the near-term outlook for the economy both worsened over the month, although the longer-term outlook is still viewed more positively. There was also a fall in the ‘time to buy a major household item’ sub-index. And there was also a monthly drop in the ‘time to buy a dwelling index.’ The level of that sub-index is still close to a five-year high and the accompanying house price expectations index was up quite strongly over the month and over the year.

This month’s survey also included extra questions on the tax offset payments that started to flow into households’ bank accounts this financial year. Among those consumers reporting having received a payment, 29 per cent said they planned to spend it all and 16 per cent planned to spend more than half, but 53 per cent planned to spend less than half of the money, including about 25 per cent who planned to save the full income tax refund.

Why it matters:

Like August’s readings on business sentiment, September’s consumer sentiment print depicts an economy lacking in confidence. Here too, rate cuts and tax rebates seem to be doing little to change the picture, with the significant exception of the housing market where sentiment does appear to have turned. And if households do save a large portion of the tax offset payments, then the hoped-for boost to a struggling retail sector could end up being much smaller than hoped.

Given the standard assumption about lags in the operation of monetary policy (the RBA reckons that it takes between one to two years for changes in the cash rate to have their maximum impact on economic activity), it would perhaps be surprising if we were seeing significant economic impacts from what is still a relatively recent shift in monetary policy at this point. But – again, the housing market aside – the announcement effect of the two rate cuts seems to have been neutral at best.

. . . and what I’ve been following in the global economy

What happened:

August delivered a bumpy ride for the global economy and for international financial markets, with a deterioration in the trade war (including more tariffs and the prospect of currency conflicts), repeated public warnings from central bankers about their strictly limited ability to offset the mounting economic damage arising from political shocks, intensifying strife in Hong Kong, inverting US treasury yield curves, more than US$17 trillion of negative-yielding debt and a whole heap of Brexit-related noise.

Intriguingly, September – at least so far – has looked a bit different. Markets even appear to have allowed themselves to get optimistic again on a range of fronts:

- US- China trade talks are scheduled to resume, and both sides have made efforts to de-escalate tensions, first with Beijing announcing that it would suspend the imposition of tariffs on some US products, then followed by Washington saying that it would push back the implementation of new tariffs on US$250 billion of Chinese goods from 1 October to 15 October.

- A series of high-profile parliamentary defeats for UK PM Boris Johnson seems to have convinced markets that there has been a meaningful fall in the risk of a no-deal Brexit.

- Hong Kong’s Chief Executive Carrie Lam announced that she was formally withdrawing the controversial extradition bill that had been the trigger for three months of mass protests.

- Italian politicians have stitched together an (unlikely?) coalition between Five Star and the Democratic party, heading off the near-term likelihood of new elections and the possible victory of Matteo Salvini’s euro-sceptical League.

- China’s central bank said that it would cut the amount of required reserves for banks, hoping to spur bank lending and hence economic growth. This latest stimulus from the PBOC is expected to be joined by easier monetary policy from the ECB this week, which under the outgoing Mario Draghi has promised further action to support activity in the euro area, and next week by the US Fed, which is under pressure from President Trump to boost the US economy and his own re-election prospects.

- The departure of John Bolton from the Trump White House has been interpreted as reducing the risk of an outbreak of hostilities in the Persian Gulf: the news prompted an immediate drop in oil prices.

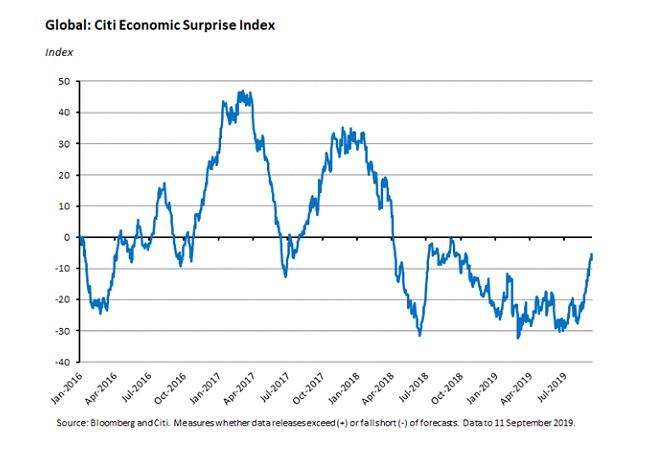

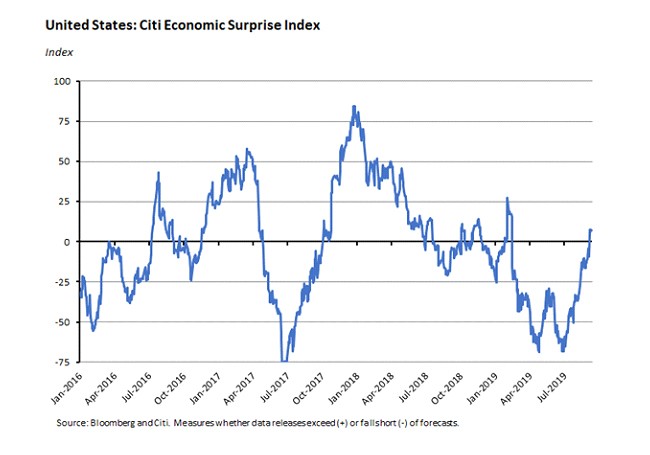

There’s also been an improvement in the relationship between market expectations and economic outcomes, with the Citibank global economic surprise indicator – which has been deep in negative territory for most of this year – staging a sharp recovery in recent weeks.

The US index, which hit lows in April and June this year, has now climbed back into positive territory for the first time since February:

Why it matters:

After all the doom and gloom of August, the shift in tone over the past week or two has been quite striking. But it’s hard to know how sustained it will be, given the precarious foundations on which at least some of the turnaround in market sentiment now rests. In the case of the US-China trade conflict, for example, we’ve already seen repeated cycles of rapprochements and breakdowns in the negotiations, so there’s a significant risk that we’re just seeing a rerun of that old and depressing pattern. In the case of Brexit, the ultimate outcome remains incredibly difficult to call. And while its true that the world’s central banks are working hard to stabilise the global economy, there are significant concerns that their ability to do so is increasingly limited (see this week’s readings, below). In other words, and despite the recent respite, global risks remain skewed to the downside.

Still, it’s been quite nice to have had a run of good news for a change. It would, of course, be even nicer if it turns out to continue.

What I’ve been reading: articles and essays

The RBA produced an extended response to 19 written questions from the House Standing Committee on Economics. The bank takes us through its views on QE and other unconventional measures (it thinks their use is ‘unlikely’ since at one per cent the RBA ‘still has scope for conventional policy easing’ but if warranted, ‘the focus would likely be on reducing the risk-free interest rate’, possibly through the purchase of government securities). The RBA also restates its position that the net effect of lower rates on households is positive, given that the sector has roughly twice as much debt as deposits. And there are several interesting attachments, including a short one (pdf) on modelling the effects of demographic change (which predicts substantial asset accumulation and a corresponding decline in the neutral real interest rate due to population ageing) and a longer one (pdf) on the relationship between monetary policy and the distribution of income and wealth in Australia (the dominant short-run impact of lower interest rates is estimated to be lower income inequality thanks to increased employment, while the net effect on wealth inequality ‘appears to be small.’)

The Department of Industry has published three new staff research papers:

- A paper developing firm-level management capability scores for Australian firms: size, foreign ownership and innovation activity are positively correlated with higher scores, as is labour productivity. There are also significant differences across industries. And Australian firms consistently score below their US counterparts.

- An update on entrepreneurship dynamics. Between 2002 and 2013, the rate of firm entry in Australia declined, indicating a decline in entrepreneurialism. Since then, the entry rate has started to increase again, although by 2016 it was still two percentage points lower than in 2013. The paper also emphasises the role played by small, young firms as an engine of job creation: between 2010 and 2015, they accounted for about 125 per cent of total job creation, while small mature firms shed jobs. Medium and large firms are also adding a lot of jobs, but on their own are not creating enough new jobs to offset the decline in jobs in small mature firms. Small young firms cover the gap and add jobs on top of that – hence a contribution of greater than 100 per cent.

- A study looking at changes in the market concentration of Australian industries between 2002 and 2016, which finds that, since 2007, market concentration has been increasing. Those increases have mostly taken place in industries that were already relatively concentrated to begin with. Along with the prior existence of a few top performers, factors positively correlated with rising concentration include export intensity (possibly reflecting the impact of the China-led mining boom) and the degree of digital maturity.

Michael Brennan, Chair of the Productivity Commission, on productivity, growth and progress. Brennan notes that ‘productivity growth in Australia has slowed materially from its recent peaks in the 1990s.’ In 2018-19, labour productivity fell by 0.2 per cent, and has averaged less than one per cent per annum for the last five years, or a bit less than half the long run average rate of two per cent growth. How might we do better? Brennan points to some sectors where we could improve resource allocation (finance, super, energy, health and some professional monopolies) but also an increased focus on how we generate new ideas and then diffuse them across the economy, including through an increased emphasis on fostering entrepreneurship, on maximising the benefits from big data, ‘a large, new renewable asset that we are only beginning to understand’, and by improving the operation of our cities.

Summaries of six new papers submitted to the Fall 2019 Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. Topics covered include the relationship between the natural rate of interest and the best inflation target (the authors think that for every one percentage point fall in the natural rate the optimal inflation target should be increased by 0.9 to one percentage point); the impact of globalisation on inflation (increasingly significant for US CPI inflation, but core and wage inflation are still largely domestic-driven); and what went wrong with Argentina’s Macri presidency.

Ken Rogoff makes the case for a progressive consumption tax.

The FT’s Gillian Tett asks, does capitalism need saving from itself? And in a similar vein, a WSJ essay argues that the changing social role of US corporations has helped transform the economic and political order in the United States.

Agustin Carsten, General Manager of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), looks at monetary policy ten years after the GFC and highlights four key challenges: (1) persistently low inflation and a change in the relationship between inflation and other macro variables has made it harder for central banks to ‘steer’ the inflation rate; (2) high debt levels combined with the search for yield has increased economic vulnerability to negative shocks (Australia’s high level of household debt is called out here); (3) limited policy room – with rates now at historic lows, there’s more emphasis on unconventional monetary policies with potentially problematic side-effects; and (4) the challenges posed by the current economic outlook, including trade wars. His conclusion (and remember, the BIS is the central bankers’ bank) is that ‘Central banks have done all that they could have’ but that now other instruments are required to support monetary policy.

Related, Mohamed El-Erian reckons that both the ECB and the Fed are easing monetary policy despite the fact that the ‘cyclical and structural factors undermining growth are beyond the direct reach of central bank tools, and the use of financial assets to boost the household wealth effect and corporate animal spirits is too ineffective to move the needle materially on economic activity.’ Instead, central bankers are more concerned about failing to validate market expectations of further stimulus, and thereby triggering a destabilising market backlash.

An interesting VoxEu column on economists at war, which suggests that the Second World War helped embed economists in government and policymaking, stimulating the development of the toolkits of macro and managerial economics along with computing.

Finally, a little bit of self-indulgence. I spotted this story in the FT about Northern England’s ‘murdered towns’. The example cited, Consett, is described as ‘home to a slew of supermarkets and discount stores, this chilly corner of northern England remains a place that lost its reason to exist.’ There’s also a picture of a bit of the town centre that’s unlikely to drive much tourist traffic. Consett is where I was born, and where – along with stints in the Middle East (my Dad ‘got on his bike’) – I spent much of my childhood. My parents are still there. I’m certainly not convinced that it’s quite as grim as depicted: I’ve still got a big soft spot for the lovely surrounding countryside of the Derwent Valley, for example. Although I suppose occasional fly-in visits from Sydney mean that I’m not going to be the best judge. As I’ve noted before, the aftermath of the huge economic shock that hit my home town back in 1980 was probably one of the things that ended up triggering my interest in studying economics.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content