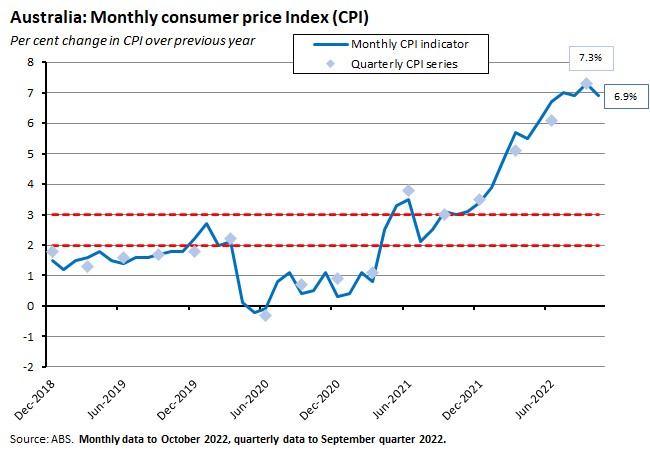

This week’s release of the ABS Monthly Consumer Price Index (CPI) Indicator surprised to the downside, with the annual rate of increase in the indicator falling to 6.9 per cent in October, down from 7.3 per cent in September and comfortably below market forecasts of a 7.6 per cent result. The annual rate of underlying inflation, as measured by the trimmed mean, also eased (to 5.3 per cent from 5.4 per cent) and came in below market expectations (5.3 per cent vs 5.7 per cent). All of which is consistent both with the RBA’s view that inflation is approaching its peak, and with the central bank’s previous decision to slow the pace of monetary tightening.

On their own, the latest monthly numbers are unlikely to be enough to dissuade Martin Place from delivering another 25bp increase in the target cash rate next week. But they will add to the debate over when it might be time for a pause in the monetary policy tightening cycle beyond the RBA meeting-free month of January.

Meanwhile, higher interest rates continue to exert pressure both on the housing market (where national housing values fell for a seventh consecutive month in November) and on consumer spending (with retail turnover in October suffering the first contraction of this year).

Finally, the Government has made further progress with its plans to reform Australia’s industrial relations (IR) arrangements in the form of the Secure Jobs, Better Pay Bill. We dive into some of the associated debates around wage growth, productivity and bargaining in a lengthy section tucked away at the end of this week’s note.

Inflation surprises to the downside in October

The ABS said that Australia’s monthly CPI rose 6.9 per cent over the year in October 2022, down from a 7.3 per cent rate of annual increase in September. The result was also below market expectations for a 7.6 per cent print.

The Bureau also reported that the monthly trimmed mean series rose 5.3 per cent in October. Again, that was below both September’s result (5.4 per cent) and the consensus forecast of a 5.9 per cent rate.

Returning to the headline CPI, key factors relating to the October result included:

- Higher prices for new housing, due to high levels of construction activity and shortages of labour and materials. In annual terms, new dwelling construction prices rose by a heady 20.4 per cent in October. At the same time, however, the monthly rate of price growth in September and October was just 0.5 per cent, down from a peak of 2.2 per cent in April 2022 and a monthly growth rate that was still above one per cent as of August this year.

- Ongoing upward pressure on rents from low vacancy rates.

- An easing in price pressures for fruit and vegetables as growing conditions improved following the disruption to supply associated with severe rainfall events earlier this year. In annual terms, price increases fell from 17.4 per cent in September to 9.4 per cent in October.

- The reinstatement of the full fuel excise tax on 29 September (from 22 cents / litre to 46 cents / litre). This lifted automotive fuel prices, which were up 11.8 per cent over the year in October, compared to 10.1 per cent in September.

- A fall in the monthly rate of increase in holiday travel and accommodation. This was due to the end of school holidays and the end of the peak tourist season for outbound travel to Europe and America, which led to a decline in airfares. As a result, the annual rate of increase fell from 12.6 per cent in October to 3.7 per cent in October.

- Updated expenditure weights that were applied to the CPI in October. According to the Bureau, the most significant change was an increase in the weight of international travel from just 0.1 per cent during the COVID period to 1.9 per cent. The ABS says the overall rate of annual increase in the CPI using the original weights would have been 7.1 per cent instead of the 6.9 per cent increase that was produced by the revised weighting structure.

The surprisingly low monthly inflation result lends support to the argument advanced a couple of weeks ago that the RBA is likely feeling comfortable with its October shift to a more gradual pace of monetary policy tightening. It’s also consistent with the central bank’s view that we may now be approaching peak inflation due to some combination of the consequences of domestic and international monetary policy tightening to date, the repair of global supply chains and a diminishing impact from high commodity prices. To that extent, it should further reinforce the case for another 25bp rate increase next week, as opposed to anything larger. Indeed, it could also bring forward the debate as to when it will be appropriate for the central bank to take a pause and consider the impact of rate increases already delivered. Given that the absence of a meeting in January will provide such a pause anyway, however, a December rate hike next week still looks the most likely outcome.

Finally, and despite the good news in this week’s release, it’s important to note that we – and more importantly Martin Place – cannot be sure that we’re now at or passing peak inflation. For a start, the monthly CPI release is a relatively new data series and comes with some limitations. The ABS itself has emphasised that the quarterly CPI remains the principal measure of household inflation. And the Bureau has also cautioned against using month-on-month changes to track inflation developments, instead suggesting users concentrate on annual or three-month-ended changes. For its part, the RBA has said that while the monthly series has been a good indicator of material turning points in consumer prices over the past few years (data for the first two months in the quarter have tended to offer a reasonable guide to the eventual quarterly outcome), its accuracy has varied over time and senior officials have commented that the RBA is still monitoring the new series and ‘trying to figure out what is the noise and what is the information in the monthly figures.’ We also know from the September Quarter 2022 quarterly CPI release that state government electricity rebates have pushed back the main impact of increased energy prices to the final quarter of this year, where they would be expected to show up in the final month of the quarter – implying more upward pressure on the headline rate is still to come, all else equal.

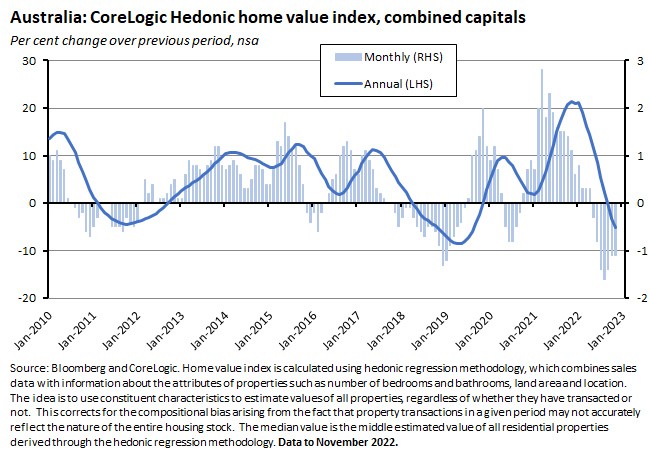

National house prices fall for seventh consecutive month in November

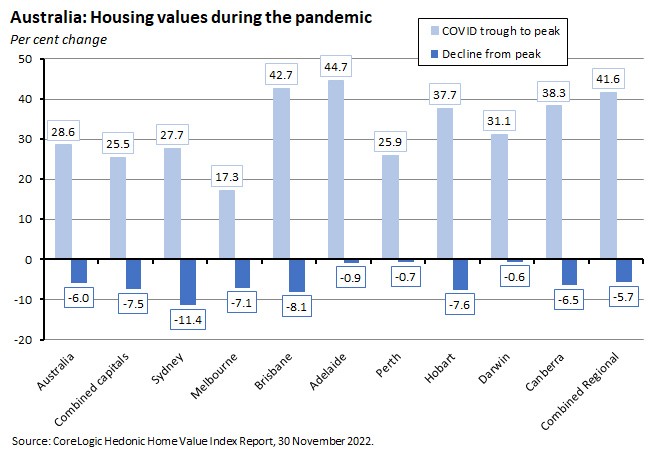

The CoreLogic National Home Value Index registered a seventh consecutive monthly decline in November, falling one per cent over the month to be 3.2 per cent lower over the year. CoreLogic noted that the national index is now about seven per cent or $53,400 below the peak value set in April 2022. That drop comes after national housing values rose by 28.6 per cent over the current upswing, adding around $170,700 to the value of the average dwelling.

The combined capitals index fell 1.1 per cent over the month and dropped 5.2 per cent over the year and has now fallen 7.5 per cent from its April 2022 peak.

Across the capital cities, only Perth (no change) and Darwin (up 0.2 per cent) did not register a monthly fall in November. Sydney remains the only capital city where housing values have fallen by more than 10 per cent from their peak – and values in that city are still more than 10 per cent above pre-COVID levels.

It’s no surprise that higher interest rates and other economic developments continue to weigh on house prices. But CoreLogic does note that the monthly pace of house price decline has been ‘consistently moderating’ since the national index slumped by 1.6 per cent in August, a trend which it reckons may reflect a decline in ‘the initial uncertainty around buying in a higher interest rate environment’, plus a low level of advertised housing stock. Still, the data provider also warned that housing risk remains skewed to the downside, with the possibility of a renewed acceleration in the pace of price decline next year, in part as the expiration of fixed rate arrangements for many existing borrowers will push up debt serviceability costs through 2023.

Several other sets of housing market-related data were published this week:

- Total building approvals fell six per cent over the month (seasonally adjusted) in October 2022 and dropped 6.4 per cent over the year. The drop was bigger than consensus expectations for a two per cent decline. The ABS said the number of approvals for private sector houses fell 2.2 per cent over the month and dropped by 11.3 per cent over the year. Approvals for private sector dwellings excluding houses slumped by 11.3 per cent in monthly terms, but were still 5.5 per cent higher on an annual basis. The value of total building approvals fell 0.2 per cent over the month, driven by a 2.1 per cent fall in the value of all residential building approvals that more than offset a 2.6 per cent monthly increase in the value of non-residential approvals.

- The RBA reported that total credit rose 0.6 per cent over the month (seasonally adjusted) in October this year to be a strong 9.5 per cent higher over the year. Housing credit rose 0.4 per cent over the month and 7.2 per cent over the year.

- The ABS said the value of total construction work done in the September quarter of this year was up 2.2 per cent over the quarter (seasonally adjusted) to $54.8 billion, beating the consensus forecast of a 1.5 per cent quarterly gain. Work done was also 1.1 per cent higher than in the same quarter last year. Total building work done rose 1.2 per cent over the quarter, but fell 1.7 per cent over the year. Residential construction rose 1.3 per cent quarter-on-quarter but fell 5.2 per cent year-on-year while non-residential construction rose 3.4 per cent over the quarter and climbed 3.9 per cent over the year. Engineering work done rose 3.4 per cent over the September quarter and increased 4.9 per cent over the year.

What else happened on the Australian data front this week?

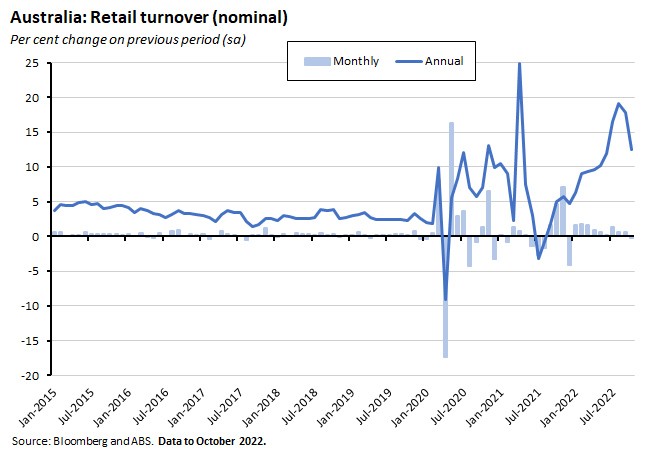

The ABS said that retail turnover fell 0.2 per cent month-on-month in October 2022 (seasonally adjusted) to be 12.5 per cent higher than sales in October 2021. This was the first monthly decline in retail turnover since December last year, with turnover down in all industries except for food retailing, which the Bureau said had been boosted by a combination of flood-related spending in affected parts of Australia, along with higher food prices. The biggest fall by industry was for Department Stores (down 2.4 per cent), followed by Clothing, footwear and personal accessory retailing (down 0.6 per cent). Turnover for Cafes, restaurants and takeaway food services fell for the first time since January 2022.

This first monthly drop in retail turnover for 2022 suggests that the combination of higher interest rates, higher prices and low levels of consumer confidence has now started to have an adverse impact on household spending decisions.

The ANZ Roy Morgan Index of Consumer Confidence rose 1.8 per cent over the week ending 27 November 2022, delivering a third consecutive weekly gain. By subindex, there were increases for ‘current financial conditions’ (a nine per cent jump following a 12.3 per cent net drop over the previous eight weeks), ‘future financial conditions’ and ‘future economic conditions’, but falls for ‘current economic conditions’ and ‘time to buy a major household item.’ By state, confidence rose in Victoria, Queensland and Western Australia but fell in NSW and South Australia. ANZ noted that confidence has now risen 5.6 per cent over the past three weeks and is back to its highest level since October this year, although added that this still leaves confidence ‘at exceptionally weak levels’. According to the same release, weekly inflation expectations dropped by 0.1 percentage points to 6.2 per cent.

The ABS reported that private new capital expenditure fell by 0.6 per cent (seasonally adjusted) in the September quarter of this year, although it was still up 1.7 per cent over the same quarter in 2021. Spending on buildings and structures was up 0.5 per cent quarter-on-quarter and 1.4 per cent year-on-year, while spending on equipment, plant and machinery fell 1.6 per cent over the quarter but rose 2.2 per cent in annual terms.

According to the same release, Estimate 4 for private capital expenditure in 2022-23 was $155.7 billion. This is 5.6 per cent higher than Estimate 3 and is 12.4 per cent higher than the corresponding Estimate for 2021-22. So, while actual investment spending last quarter turned out to be weaker than market forecasts (the consensus had anticipated an increase of 1.5 per cent vs the actual fall of 0.6 per cent), these results suggest that the outlook for investment over 2022-23 remains healthy.

New ABS data on Managed Funds shows that during the September 2022 quarter, total funds under management fell by $0.2 billion to $4,306.1 billion.

The latest RBA index of Commodity Prices. Preliminary estimates for November 2022 show the index falling by five per cent in SDR terms over the past month and dropping by 6.8 per cent in Australian dollar terms. Over the past year, the index is up 19.1 per cent in SDR terms and 22.3 per cent in Australian dollar terms.

On the Dismal Science podcast this week, inflation is showing signs of waning. Have we put the genie back in the bottle? Plus, with protesters on the streets, is the Chinese grand bargain for stability and growth at an end?

Other things to note . . .

- The latest ANZ Stateometer covers data for the September quarter 2022.

- Taking the long view - the labour share of national income in Australia since the 1860s.

- Boosting Australia’s cyber defences.

- The Grattan Institute’s 2022 Prime Minister’s Summer Reading List.

- A speech from the RBA’s Jonathan Kearns on the Past, present and future of Securitisation and the Australian residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) market.

- RBA Governor Lowe’s Appearance before the Senate Economics Legislation Committee (video).

- The FT’s Martin Wolf considers how to think about policy in a polycrisis. AFR version.

- Also from the FT, a Big Read on a week that could unravel the global oil market.

- A WSJ piece on China’s growth challenges, Chinatalk on the protests in China, and the Economist magazine says China’s economy cannot cope with Beijing’s zero COVID policy.

- On the reshuffling of global supply chains.

- A Guardian Long Read examines West Africa’s emerging Megalopolis.

- The ILO’s Global Wage Report reckons global monthly wages fell in real terms over the first half of this year, marking the first negative global real wage growth seen this century.

- Matt Yglesias on how the US Fed Chair is bending time and upending the business world, as high interest rates reshape the economic, financial and business environment. (In part, this is a response to the ‘Tech in mid-life crisis’ link from last week’s roundup, that had presented an alternative to the traditional interest rate view.)

- Brad Setser is back blogging with a post on the new geopolitics of global finance.

- An analysis of post-COVID labour shortages across the OECD.

- Nature article on how the Great Depression shaped people’s DNA by accelerating ageing.

- Econtalk podcast on the power of quitting. This is (sort of) a counterpoint to a previous Econtalk podcast on the importance of grit.

- The Conversations with Tyler podcast talks with Jeremy Grantham. For some context, here is Grantham’s latest piece, on Entering the Superbubble’s Final Act.

A deep dive into IR reform, wage growth and productivity

The government's new industrial relations bill passed Parliament today. The IR reforms involve a number of changes to Australia’s Workplace Relations laws via The Fair Work Legislation Amendment (Secure Jobs, Better Pay) Bill 2022. The Bill – originally introduced to Federal Parliament on 27 October – contains a wide range of measures relating to bargaining, job security, gender equity, compliance and enforcement, workplace conditions and protections and workplace relations institutions.

Designed to meet the Government’s pre-election pledges to ‘promote job security, help close the gender pay gap, modernise the workplace bargaining system and get wages moving after a decade of stagnation’, one particular focus of the legislation is low wage growth. The government has accepted arguments that targeted policies are needed to lift wage growth though IR and other institutional changes, and to this end, the Bill is pushing changes that are intended both to improve productivity (by restoring some of the lost attractiveness of enterprise bargaining) and to rebalance labour market power (by promoting multi-employer bargaining). The challenge is that there are potential tensions between the former and the latter.

The context of low wage growth

The context for the push on wages is that Australia has suffered from a prolonged period of unusually low wage growth that extends back to 2012-13. In 2017, for example, in response to a request from then-Treasurer Scott Morrison for a ‘thorough analysis’, Treasury’s Analysis of wage growth in Australia opened with the judgement that:

‘On a variety of measures, wage growth in Australia is low. This is true across the States and Territories, across industries and across both the public and private sectors. Real wage growth…has also been low’ and ‘recent subdued wages growth has been experienced by the majority of employees, regardless of income or occupation.’

Similarly, the RBA’s final pre-pandemic annual research conference in 2019 made low wage growth its organising theme, with the conference overview paper explaining that, following a sharp decline in wage growth between 2013 and 2016, wage growth in Australia had been low across a range of different measures of labour costs, that growth in the wage price index (WPI) was running at a lower than average rate across all industries and states, and that the dispersion in wage growth across jobs was at its lowest level in the 22-year history of the WPI.

More recently, in the post-pandemic period, while a tighter labour market has seen nominal wage growth pick up, the rate of increase has nevertheless been low relative to the level of spare capacity in the economy (as measured by the unemployment, underemployment and underutilisation rates). Moreover, nominal wage growth has lagged inflation, leading to falling real wages.

The wage -productivity relationship

Economic theory says that, in the long run, nominal wage growth should be driven by a combination of growth in labour productivity (the number of hours required to produce a unit of GDP) and inflation expectations, since employees will care about the real purchasing power of their nominal incomes. Real (inflation-adjusted) wage growth will therefore largely be driven by growth in labour productivity over the long term. This message is one that has been delivered frequently by the Productivity Commission (PC), which argues that almost all Australian wage growth since Federation appears to be due to labour productivity growth. All else equal, then, a slowdown in the pace of productivity growth would likely be associated with a slowdown in the rate of growth of wages. And since the evidence suggests that the rate of growth of productivity in Australia has declined over the past decade, this is likely an important source of lower wage growth. However, there is also some evidence that the size of the passthrough from productivity growth to wage growth may have declined after 2012-13.

A range of factors can lead to a divergence between productivity and wage growth in the short and medium term. For example, two potentially important cyclical factors that determine wage growth are the degree of slack in the labour market and the terms of trade. All else equal, wage growth is likely to be lower when spare capacity (unemployment and underemployment) is higher and vice versa. And particularly importantly for Australia, increases in the terms of trade due to rises in export prices are associated with rising real incomes. During the mining investment boom, the PC estimates that real wages in Australia rose at about twice the rate of labour productivity.

Structural changes in the economy can also shift the relationship between wage and productivity growth. Technological change, for example, is likely to be important. As is the level of economic dynamism in the economy – work by Treasury has found that higher job-to-job transition rates in Australian local labour markets are associated with higher wage growth, including for those workers who stay in their job. Pre-pandemic, labour mobility in Australia had been on a downward trend and had then stagnated at a relatively low level. Again, the transition to a greater role for services in the economy could weigh on aggregate measures of wage growth, to the extent that growth in services employment has been concentrated in below-average wage industries such as accommodation and food services. The structural factor that is particularly important in the current context, however, is the relative bargaining power between employers and employees. Shifts in the balance of power could reflect the impact of more intense international competition (globalisation) and the threat of technological change (automation) or be a product of changes in labour market structures and institutions such as rates of union membership (although work by the RBA covering 1991 to 2017 found that changing unionisation patterns were unlikely to account for much of the decline in Australian wage growth over that period.)

The role for IR reform (1): Productivity and the BOOT

In this context, the recent proposed changes to IR laws can be seen as seeking to boost wage growth in Australia through two main channels: (1) by making changes to the current framework that are intended to lift productivity growth, and (2) by making changes designed to tilt the balance of bargaining power towards employees and / or their representatives (primarily unions). Simplifying a bit, we could say that reforms to the Better Off Overall Test (BOOT) are mainly targeted at the former, while the promotion of multi-employer bargaining is mainly aimed at the latter.

Starting with productivity, one of the motives behind the 1990s Hawke-Keating labour market reforms and their promotion of Enterprise Bargaining Agreements (EBAs) in particular, was to encourage productivity growth. The idea was that enterprise level bargaining was correlated with higher productivity growth, reflecting the greater flexibility afforded by decentralisation (for example, it should be easier to better align wages and conditions according to specific circumstances), better employee-firm matching (more productive firms should be able to offer higher wages and better conditions and thereby attract more productive workers) and by allowing scope for more individual enterprise-level innovation and experimentation.

Unfortunately, the PC recently concluded that Australia’s current Enterprise bargaining system ‘remains unnecessarily complex and inefficient’ and that ‘bargaining is still time-consuming and resource intensive for parties.’ Partly as a result, EBAs have declined across industries. According to the latest ABS data, as of May 2021, 23 per cent of employees had their pay set by award only, 35.1 per cent by collective agreement (down from 42 per cent in 2012) and 37.8 per cent by individual arrangement (4.1 per cent were owner managers of incorporated enterprises).

Back in 2021, the Business Council of Australia’s review of the state of enterprise bargaining in Australia argued that while EBAs remained ‘the best way to keep people in work and to enable businesses to grow and succeed so they can pay higher wages and employ additional workers’, the system was no longer working. In particular, the number of active agreements had fallen to the lowest level in more than two decades; complexity and uncertainty around the BOOT meant that employers and employees were choosing not to renegotiate agreements; when renegotiations did happen, they took longer; and some employers were not using EBAs at all, but defaulting back to awards. Another consequence was that the share of people working under a lapsed (or ‘zombie’) agreement had risen to almost 40 per cent of all federally registered agreements, potentially leaving workers stuck on their old pay rate and without a pay rise.

In line with this BCA review, an increasingly common take was that the BOOT, which is carried out by the Fair Work Commission (FWC) when it is approving EBAs, had become a key constraint on the adoption of EBAs. The BOOT is intended to ensure that each employee covered by an EBA is better off overall when compared to their relevant award. But the Government now recognises that the complexity of the BOOT has led to an increase in approval times and encouraged some employers to give up on EBAs altogether. The Government has therefore proposed to make the BOOT simpler and easier to apply, including by: applying the BOOT as a global assessment to ensure each employee would be better off, rather than requiring a line-by-line comparison between the proposed agreement and the relevant modern award; requiring the FWC to only consider employees, patterns, or kinds of work or types of employment that are reasonably foreseeable at the test time (reducing the time spent on unlikely hypothetical or edge cases); and requiring the FWC to give primacy to any common view shared by employees and employers as to whether the agreement passes the BOOT. It has also proposed other measures to simplify the EBA approval process and to reduce the scope for procedural errors and unhelpful complications.

The role for IR reform (2): Multi-employer bargaining and labour market power

What about bargaining power? While Government says that it believes single Enterprise bargaining should remain ‘at the centre’ of Australia’s Workplace Relations System, it is also using IR reform to promote multi-employer bargaining. It’s important to note that there are some pro-productivity arguments that can be deployed here (for example, it could be argued that multi-employer bargaining might allow smaller employers to take advantage of any economies of scale in bargaining by sharing the burden and costs across firms; and in the presence of sunk cost investments, industry-wise bargaining can increase incentives for capital upgrades). Even so, the main focus in this case is more likely to be on improving the overall bargaining position of employees to improve the pass through from productivity growth to wage growth.

Current arrangements under the Fair Work Act already allow for multi-employer bargaining under two streams, at least in theory. But in practice those rules have been so restrictive they have been rarely if ever used. One stream relates to low-paid bargaining and applies to low-paid employees who have traditionally not participated in enterprise bargaining. The second relates to single-interest bargaining, which applies to multiple employers operating with a single interest and under the same regulatory structure (such as franchises). The Government’s plan is to make multi-employer bargaining easier under both streams:

- With regard to low-paid bargaining, it plans to rename the stream as the Supported Bargaining Stream. The Bill would then require the FWC to make a Supported Bargaining Authorisation if it was satisfied that it was appropriate for the relevant employers and employees to bargain together. To that end, it would be directed to consider the prevailing pay and conditions in the relevant industry/sector, including whether low rates of pay prevailed; whether employers have clearly identifiable common interests which may include geographic location, the nature of the enterprises involved, and the terms and conditions of employment, and whether the likely number of bargaining representatives is manageable.

- The Government also intends to make it easier to apply to the FWC for a single interest employer authorisation. Employee representatives (unions) would be able to apply for a single interest employer authorisation to cover two or more employers, subject to majority support of the relevant employees. Factors determining whether employers could be deemed to have a common interest could include the nature of their enterprises, the terms and conditions of employment, their geographical location, and whether they’re subject to a common regulatory regime. Employers and employees would also be allowed to apply to the FWC to add or remove the name of an employer for the authorisation to bargain together, or to extend coverage of an existing single interest employer organisation to a new employer and its employees, subject to specific requirements. Under a carve out, small businesses (initially defined as those with less than 15 employees) would not be subject to a requirement to bargain in this stream but would only participate voluntarily.

Some of the thinking behind the Government’s proposed changes to multi-employer collective bargaining is that it will boost the bargaining power of low-paid workers in industries such as aged care, child care and disability support. The shift is also intended to reflect the changing nature of industrial organisation and the increased role of labour hire, independent contracting and outsourcing by, for example, allowing a union representing the cleaners and security guards operating in the same commercial building to negotiate directly with the building owner or services management company, rather than with the multiple agencies responsible for cleaning and security contracts. And the Bill is also intended to address the restraint on wage growth currently imposed by the proliferation of zombie agreements.

Employer organisations generally dislike the idea of multi-employer bargaining. They have objected both to the detail (arguing, for example, that the definition of ‘small’ firms is far too low, and that the definition of a ‘common interest’ to be applied by the FWC is far too loose) and to the broader concept, worrying that the changes could prompt widespread strikes, industrial action and disruption to supply chains while also undermining productivity and flexibility.

In its own recent assessment of Australia’s labour market, the PC reckoned that the impact of changes to multi-employer bargaining would ‘depend very much on its design features.’ While acknowledging that it could reduce transaction costs for some small employers and improve the overall bargaining position of employees, the Commission also warned that, if poorly designed, it could:

- Risk reducing the productivity benefits associated with firm-level bargaining by leading to a ‘one size fits all approach’ for wages and conditions that could prevent more productive firms from attracting higher productivity workers;

- Require firms to compromise some of their firm-specific requirements and flexibilities to ensure an agreement was suitable for the other firms involved; and

- Potentially encourage cost-collusion and broader forms of anti-competitive conduct among businesses, which could increase prices and/or reduce quality for consumers.

The PC concluded that ‘any changes to the Fair Work Act to increase the use of multi-employer and industry/sector wide bargaining are likely to have uncertain implications for productivity…and should be undertaken with caution and be subject to detailed, rigorous and transparent analysis.’ It also warned that ‘removing restrictions on protected industrial action and bargaining orders would pose significant risks to productivity and wages if it led to wider industrial action, with impacts on the broader economy. In the extreme, multi-employer agreements could morph into industry-wide agreements, undermining competition across industries, weaking the growth prospects of the most productive enterprises…and creating wage pressures that cascade into other industries.’

The state of play and summing up

To secure a deal on the Bill, the Government has agreed to several changes including those proposed by a recent Senate committee. Some of these involved amending the definition of a ‘small business employer’ for the single interest bargaining stream to fewer than 20 employees instead of fewer than 15, and empowering the FWC to remove a business with fewer than 50 employees from a single interest authorisation either where their circumstances have changed or where the majority of employees votes for it, subject to appropriate safeguards. Another change will give the Minister a specific power to declare that a particular industry or occupation is eligible for the supported bargaining stream. The Government has also agreed to ‘establish an ongoing statutory committee to provide advice on economic inclusion, including policy settings, systems and structures, and the adequacy, effectiveness and sustainability of income support payments ahead of every Federal Budget.’

From the perspective of boosting wage growth via higher productivity growth, the revised changes to Australia’s workplace relations laws could have a positive effect if they are successful in reducing the complexity and thereby approving the attractiveness of (single) Enterprise bargaining and if EBAs are then able to deliver a pickup in productivity growth.

Unsurprisingly, efforts to shift the balance of power in the labour market are far more controversial. All three peak employer organisations (the BCA, ACCI and AiG) have recently reiterated their opposition to the Bill and in particular to its promotion of multi-employer bargaining. As noted above, from a Government perspective, these measures are intended to boost access to bargaining for low-paid workers and to account for changes in labour market organisation such as outsourcing that it reckons have tilted the IR playing field against employees. But from the point of view of employers, they risk imposing a productivity-sapping ‘one-sized fits all’ straitjacket on terms and conditions, adding further complexity to an already-complex system, and threaten to lead to a sharp increase in the number and size of industrial disputes.

The risk in this part of the strategy, then, is that in making efforts to improve the negotiating power of employees and thereby boost wage growth in the near term, there could be offsetting losses to potential productivity growth that serve to undermine prospects for wage growth in the longer term.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content