Despite a reasonably busy week on the domestic data front, attention remained focused on next week’s RBA meeting, where the consensus continues to expect a first hike for the cash rate target since June. Certainly, there was nothing in this week’s releases that looked likely to dissuade the central bank from another round of monetary policy tightening. The monthly increase in September retail sales was much stronger than the median market forecast (0.9 per cent vs 0.3 per cent) while the CoreLogic National Home Value Index rose again, a 0.9 per cent increase over the month in October taking national home values back to just half a per cent below the record high they reached in April last year.

According to the data provider, at current rates, dwelling values are on track to hit a new record high mid-way through this month. Rental vacancies, meanwhile, dropped to a new record low last month. With housing approvals remaining soft as migration-powered population growth continues to surge, the demand-supply imbalance in housing looks set to persist.

While we have been waiting to see what the RBA Board has in mind, the IMF and the OECD have both recently delivered updates on the Australian economy, including the usual dose of policy advice. In terms of the issue at hand, the Fund recommended ‘further monetary policy tightening to ensure that inflation comes back to the target range by 2025 and minimise the risk of de-anchoring inflation expectations.’ It also suggested that the federal government and state governments could help out the central bank with macro stabilisation by slowing down the rate of public investment. In terms of structural economic reforms, both international institutions suggested more work was needed on Australia’s tax system, including a shift from direct to indirect taxes. There is more detail on their (quite lengthy) lists of suggested reforms below.

In a bumper issue this week, we also take a look at the latest World Bank assessment of potential oil market risks associated with the current turmoil in the Middle East, the RBA’s thoughts on emerging threats to financial stability, the outcome of the recent independent evaluation of the pandemic era JobKeeper program, and some thoughts from the incoming Productivity Commission Chair on what makes tax reform in Australia so difficult.

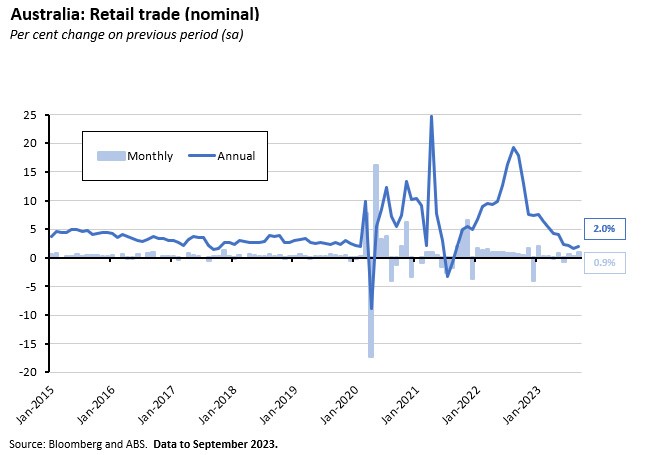

Retail turnover rise of 0.9 per cent in September 2023

The ABS said that retail turnover rose 0.9 per cent month-on-month (seasonally adjusted) in September 2023 to be up two per cent over the year. That was markedly stronger than the median forecast for a 0.3 per cent monthly increase and the fastest monthly growth reported since January this year.

The ABS said that September’s unexpectedly strong monthly growth was the joint product of several factors, including: a warmer-than-usual start to Spring, which lifted spending on hardware, gardening and clothing items at department stores, household goods and clothing retailers; the release of a new iPhone model; the introduction of the Climate Smart Energy Savers Rebate Program in Queensland which encouraged households via cashback offers to upgrade appliances such as washing machines, dishwashers, refrigerators and dryers; and a temporary boost in turnover for pharmacies after the introduction of 60-day prescriptions for medicines that manage ‘stable, ongoing conditions’ led to an initial shift forward of income from PBS medicines. Rapid population growth due to very high rates of net overseas migration is also likely contributing to overall spending growth (which is consistent with relatively weak spending in per capita terms).

Still, it is also worth noting that the Bureau commented that underlying growth in retail turnover remained historically low, highlighting that retail turnover in trend terms was up only 1.5 per cent on September 2022 – the smallest trend rate of annual growth in the history of the series.

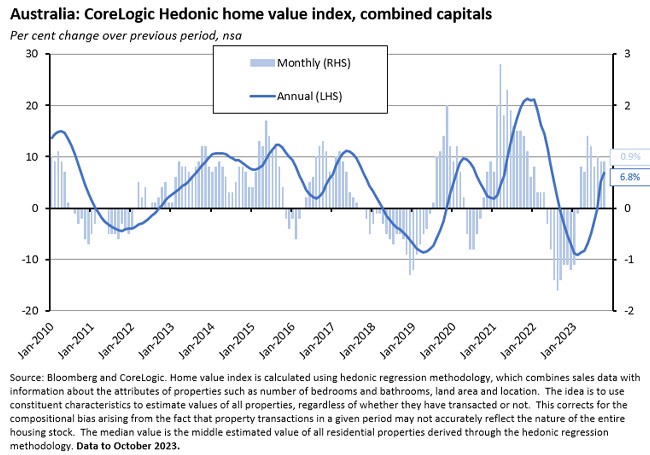

House price rise in October 2023

CoreLogic’s national Home Value Index (HVI) rose 0.9 per cent over the month in October 2023, accelerating from a (downwardly revised) 0.7 per cent monthly increase in September. The HVI was up 5.6 per cent over the year and has risen 7.6 per cent from its January low, leaving it just half a percent below the historic high it reached in April 2022. According to CoreLogic, it is set to reach a new record high mid-way through this month.

The combined capitals index also rose 0.9 per cent over the month to be up 6.8 per cent over the year as dwelling values rose across October in every city except Darwin. Prices in Sydney, Perth and Brisbane have now risen by more than ten per cent over the first ten months of this year.

CoreLogic said that the trend in dwelling stock levels continues to be a critical driver of prices. After ten months of below-average vendor activity, the flow of new capital city listings has increased and is now almost 12 per cent higher than a year ago. While total listings (new listings plus relistings) are still lower than in October 2022, housing inventory levels are rising. At the same time, buyer activity has slowed. The net result is that although home values continue to rise, they are doing so at a slower rate: capital city home values rose 3.7 per cent over the three months to June but more recently increased by 2.6 per cent over the three months to October.

Meanwhile, rental vacancies fell to a new record low in October 2023, reaching 0.9 per cent across the combined capital cities. Rents have now risen in every month for the past 39 months, although CoreLogic reckons that gross rental yields have peaked as values continue to rise and the rate of rental growth has slowed.

Although prices keep heading up, CoreLogic’s take is that the housing market faces a mix of headwinds and tailwinds. The former includes rising affordability pressures, increasing debt service burdens, very low levels of consumer confidence, and the expectation of another RBA rate hike. The data provider reckons that mortgage repayments on a $500,000 loan have already risen by about $1,040 a month since the RBA started to tighten monetary policy last year, and another 25bp hike would add an additional $81 a month. But pushing in the opposite direction are tailwinds from a still-tight labour market, record low rental vacancy rates and rapid population growth.

The latest policy advice from the IMF and OECD

This week, the Fund published the Staff Concluding Statement of the IMF 2023 Article IV Mission to Australia. Key messages from the IMF’s latest assessment of the Australian economy included:

- Although the economy is slowing, it remains resilient, supported by high net migration, resilient private investment, strong public investment, and net exports. The IMF thinks the current slowdown will deepen, however, as the bulk of the impact from past interest rate rises will materialise in coming quarters. Meanwhile, inflation is falling ‘but remains too high’ and the IMF thinks it will remain outside the target band for ‘an extended period.’

- The IMF recommends ‘further monetary policy tightening to ensure that inflation comes back to the target range by 2025 and minimize the risk of de-anchoring inflation expectations’. It also says the ‘Commonwealth Government and state and territory governments should implement public investment projects at a more measured and coordinated pace, given supply constraints, to alleviate inflationary pressures and support the RBA’s disinflation efforts.’

- Over the medium term, the IMF says all levels of government ‘need to reduce structural deficits and promote economic efficiency’, improve expenditure outcomes, and ‘contain structural spending growth in health, aged care, and the NDIS.’

- The Fund supports ‘comprehensive tax reforms, including rebalancing from high direct taxes to underutilised indirect taxes.’ It also says that ‘at the state and territory level, implementing recurring property taxes in lieu of stamp duties on housing transactions would promote housing affordability, more efficient use of the housing stock, labour mobility, and more stable tax bases over the medium term.’

- With respect to the housing market, given that prices are rising again (as noted above), the IMF suggests that ‘additional borrower-based tools, such as loan-to-value and debt-to-income limits…should be considered to boost the overall macroprudential toolkit and contain build-up of risks.’ In the longer term, the Fund says that Australia needs a greater housing stock and that ‘supportive planning and land-use policies are critical.’

- The IMF also reckons that ‘efforts to jump-start productivity growth should be a priority,’ including by promoting innovation via investment in digital infrastructure, a more open FDI regime and better labour market integration of skilled immigrants, and by addressing skills shortages.

- The IMF still thinks that ‘an economy-wide carbon price would be the most effective way to achieve net zero’ but that in a second-best world, the authorities should consider gradually expanding the coverage of the Safeguard Mechanism to a greater share of economy, should make efforts to ensure the integrity of carbon offsets, and should consider the use of ‘feebates’ in the energy and transport sectors.

The IMF isn’t the only international economic institution offering views on the Australian economy. Last Friday brought the publication of the latest OECD Economic Survey of Australia. The OECD reckons that real GDP growth will slow from 1.8 per cent this year to 1.3 per cent in 2024, the headline inflation will ease from 5.5 per cent to 2.8 per cent over the same period, and the unemployment rate edge up from 3.7 per cent to 4.2 per cent.

The OECD also offered its usual list of proposed reforms and policy advice. Its policy suggestions included:

- Improve mechanisms for fiscal dialogue between the federal government and the states to manage spending pressures.

- Raise revenue by reducing exemptions in the GST tax base (including for education, healthcare, food, and water) while also giving consideration to increasing the rate. Any regressive effects should be offset by providing compensation to low-income households.

- Further reduce tax concessions on private pensions to more closely align their tax treatment with other forms of saving and investment.

- Seek to reduce hospitalisation rates and growth in spending on health care by encouraging more preventive health policy and more patient care in primary settings.

- Design more effective policies related to Indigenous Australians.

- Make the composition of skilled migration more responsive to the skill needs of industry.

- Improve education policies to ensure that the workforce has strong foundational skills that can easily adapt to structural changes – for example, by providing all teachers with access to high-quality and evidence-based curriculum resources.

- Introduce greater flexibility in zoning systems to improve the ability of new businesses to enter and grow in desirable locations and to benefit residential housing supply through enabling an increase in housing density.

- More closely align Australia’s merger regime with other OECD economies, including by considering requiring companies to give pre-merger notification to the competition authority for transactions above a defined threshold and introducing divesture as a legislated remedy.

- Reduce the gender gap in hours worked by reducing the speed of benefit withdrawal to lower effective marginal tax rates, potentially funded by removing Family Tax Benefit Part B for couple families.

- Further increases in the JobSeeker benefit rate along with reforms to encourage those on the payment to increase working hours.

- Initiatives to encourage further supply of childcare through the private childcare sector should be coupled with measures to increase the provision of non-standard hours of care.

- Increase the duration of parental leave, the rate at which it is paid, and the share of leave reserved specifically for fathers.

- Implement programs that focus on promoting early work experience, apprenticeships and mentoring arrangements for females studying STEM and ICT and men studying caring professions.

- Consider scaling up and refocusing public funding towards the development and demonstration of clean energy and energy-efficiency technologies.

- Consider further reforms of the Safeguard Mechanism to guarantee a significant reduction in emissions, including by switching from baselines based on emissions intensity to limits on total emissions.

- Align the various state subsidy programs for electric vehicles, introduce stringent federal fuel economy standards, raise fuel taxes, and reconsider existing fuel tax credits.

- Regularly update energy efficiency requirements in the National Construction Code to keep in line with international standards.

- Introduce mandatory disclosure of climate-related risks in cases such as the sale of property along with the incorporation of climate hazard considerations in land-use planning.

The World Bank on the risks of another global oil shock

The latest World Bank Commodity Market Outlook contains a preliminary assessment of the conflict in the Middle East for commodity markets. The reports’ authors begin by noting that commodity markets’ initial response to the crisis has been muted, indicating the expectation that – assuming no escalation – the turmoil will have only a limited impact on oil prices. The World Bank’s baseline scenario, then, is for weaker global demand to lead to an overall fall in energy prices this year. But they also note that historical precedent shows that ‘escalating conflict in the region could substantially disrupt commodity supply…this could have destabilising implications for the global economy.’

The most prominent two examples of past disruptions to Middle Eastern oil markets are (1) the October 1973 – March 1974 Arab Oil Embargo which saw OPEC quadruple official oil prices, leading to a permanent step increase in real oil prices, a spike in global inflation and the 1975 global recession and (2) the Iranian revolution which led to a more than doubling of oil prices, a significant decline in global economic activity and a sharp rise in global inflation. Other significant regional geopolitical shocks have included the Iran-Iraq War, the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, the Libyan Civil War, and the imposition of sanctions on Iran.

The paper’s authors argue that current market conditions ‘differ markedly’ from those prevailing around previous major oil shocks: the world economy is now considerably less oil-reliant (oil intensity – the amount of oil needed to produce one unit of GDP – has fallen from 0.12 tons of oil equivalent (toe) in 1970 to 0.05 toe in 2022; oil supply is now more geographically diversified; and past shocks prompted the creation of shock absorbers such as strategic oil reserves and the establishment of the International Energy Agency (IEA).

The paper considers three scenarios associated with various levels of disruption to the global oil supply. Under the small disruption scenario, global oil supply is reduced by between 0.5 million and 2 million barrels per day (mb/d), which would be comparable in impact to the 2011 Libyan Civil War. As a result, oil prices rise by between US$3/b and US$12/b over the World Bank’s Q4:2023 baseline of US$90/b. Under the medium disruption scenario, global oil supply is reduced by between 3mb/d and 5mb/d, comparable to the loss of supply experienced during the 2003 Iraq War. This would see an initial increase in oil prices of between $19/b and US$31/b over baseline. Finally, under the large disruption scenario, global oil supply falls by 6mb/d to 8mb/d, in line with the initial disruption associated with the 1973 oil embargo. This scenario would see oil prices rise by US$50/b to US$67/b above the baseline.

The Bank’s analysis also warns that a significant rise in oil prices would spill over into commodity markets through higher production costs, leading to higher prices for food and metals. The Bank is particularly concerned about the potential threat to food security.

What else happened on the Australian data front this week?

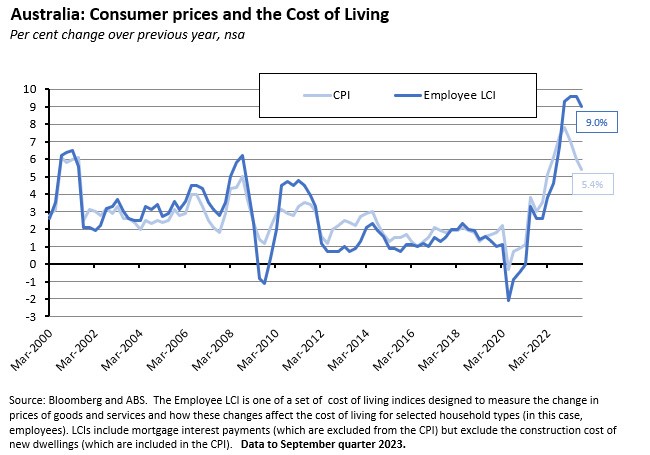

The ABS published numbers for its Selected Living Cost Indexes (LCIs) for the September quarter 2023. All five LCIs rose between 0.5 per cent and two per cent in quarterly terms and by between 5.3 per cent and nine per cent in annual terms. The largest cost of living increase was experienced by employee households where the relevant LCI rose by two per cent over the quarter and nine per cent over the year (the latter down slightly from the June quarter 2023’s 9.6 per cent annual rate of increase). That reflected increases in mortgage interest charges, which rose by 9.3 per cent in the September quarter of this year after jumping by 9.8 per cent in the preceding June quarter. In annual terms, the rate of increase in mortgage interest charges fell to a still substantial 68.6 per cent from 91.6 per cent. Other major sources of rising cost pressures were other insurance and financial services (in the form of rising premiums for house, house content and motor vehicle insurance) and transport (higher automotive fuel prices).

New loan commitments for housing rose 0.6 per cent over the month (seasonally adjusted) in September 2023 but were still down 4.7 per cent relative to September 2022. The ABS said that lending to owner occupiers edged lower by 0.1 per cent in monthly terms and fell 8.4 per cent in annual terms. In contrast, investor lending rose two per cent month-on-month and 2.6 per cent year-on-year. The Bureau also said that personal fixed term loans grew by 2.7 per cent over the month and 12.1 per cent over the year.

The ABS said that the total number of dwellings approved fell 4.6 per cent over the month (seasonally adjusted) in September 2023 and was down 20.6 per cent in annual terms. Approvals for private sector houses also fell 4.6 per cent month-on-month and dropped 12.6 per cent year-on-year, while approvals for private sector dwelling excluding houses were down 5.1 per cent in monthly terms and slumped 33.1 per cent on a yearly basis.

The RBA published financial aggregates for September 2023. These showed total credit for housing growing by 0.4 per cent over the month (seasonally adjusted) to be 4.2 per cent higher over the year. Personal credit growth rose 0.6 per cent month-on-month and 2.3 per cent year-on-year.

According to the ABS, Australia ran a merchandise (goods) trade surplus of $6.8 billion in September 2023 (seasonally adjusted). That was down $3.4 billion from August’s trade surplus. (The Bureau is no longer reporting monthly international trade data for services, although the ABS did provide a guide to compiling monthly estimates.)

New ABS data on Australia’s population by country of birth shows that in 2022, 29.5 per cent (about 7.7 million people) of Australia’s population (about 26 million) was born overseas. That’s up from 29.3 per cent in 2021 but still below the 29.9 per cent reached in 2020. According to the ABS, in the first country-wide Australian census in 1891, 32 per cent of the population were born overseas. That share fell to a low of ten per cent in 1947 and since then trended higher until 2021. People born in England (961,000) continue to be the largest group, followed by India (754,000), China (597,000) and New Zealand (586,000). The English-born share peaked at just over a million in 2013 while the Chinese-born share peaked in 2019 at 661,000. Over the past decade, the fastest-growing migrant group was people from India.

The ANZ Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence Index fell 3.2 points to an index reading of 75 in the week ending 29 October. The index is back down to its lowest level since early August this year and all the subindices dropped over the week, with the largest drops for ‘current financial conditions’, ‘current economic conditions’ and ‘time to buy a major household item’. ANZ noted that the fall in confidence followed a higher-than-expected inflation reading and a growing consensus that the RBA would hike interest rates again. Weekly inflation expectations fell by half a percentage point to 5.2 per cent.

The ABS released an experimental Australian Transport Economic Satellite Account, which estimates that transport activity contributed 7.9 per cent ($164.4 billion) to GDP in 2020-21. Total transport activity was the second largest industry contributor to the Australian economy, behind only mining, and employed around 1.2 million people. Of that total $164.4 billion contribution, $86.8 billion came from the transport industry itself while the balance of $77.7 billion came from other industries where in-house transport was an integral part of daily business, led by construction ($40.3 billion), agriculture, forestry, and fishing ($17.8 billion), and manufacturing ($15.8 billion).

According to the ABS’s Education and Work Australia, of people aged 15-74 in 2023, 61 per cent were fully engaged in work, study, or both and 63 per cent had attained a non-school qualification (certificate, diploma or degree).

Last Friday, the ABS published the 2022-23 Australian system of national accounts. According to the Bureau, the Australian economy grew by three per cent in real terms last financial year, but only by one per cent in per capita terms. Labour productivity – as measured by real GDP per hour worked – fell 3.7 per cent while real unit labour costs were roughly flat (up just 0.1 per cent). In current price terms, GDP rose 9.8 per cent while the household saving ratio fell to 4.3 per cent.

Other things to note . . .

- Brad Jones, RBA Assistant Governor (Financial system) gave a speech on Emerging Threats to Financial Stability – New Challenges for the Next Decade. According to Jones three new ‘inside risks’ (those emerging from within the financial system) could include (1) much more rapid deposit runs due to new digital technology such as the herding effects associated with social media interacting with new balance sheet vulnerabilities (think of some mid-tier US banks’ exposure to the ‘crypto-winter’ earlier this year); (2) systemic risks arising from entities that are not systemically important on an individual basis, partly because contagion risks has increased as the speed of money and information flows can magnify herding effects and because of procyclicality in parts of the asset management industry (for example, when funds are tied to similar benchmarks) which are not subject to the kind of intensive regulation associated with deposit-taking institutions; and (3) structurally higher interest rate volatility reflecting the end of the great moderation (a world of more supply shocks linked to changes in globalisation, climate change, geopolitics and the energy transition), a higher and more volatile bond premium (due to increased uncertainty over future inflation outcomes and real policy rates plus structural supply and demand imbalances in the market for government bonds), and reduced smoothing from price-insensitive buyers (a smaller bid from central banks). ‘Outside risks’ (those arising outside the financial system) include (1) geopolitical risk and (consequently) geoeconomic fragmentation and the danger of outright conflict; (2) operational risks arising from the increased digitalisation of financial services, including the risk of cyber-attack, the role of critical technology service providers, and the implications of AI; and (3) climate change.

- Treasury published the final report of the Independent Evaluation of the JobKeeper Payment. Key findings were that:

- JobKeeper was effective in achieving its stated objectives – it preserved employment (estimates suggest it saved between 300,000 and 800,000 jobs or between 2.5 to six per cent of pre-pandemic employment), it reduced the risk of labour-scarring by maintaining employee-employer relationships, and it prevented large-scale business failures.

- These significant gains came at significant fiscal costs. While the economic cost (inhibiting productivity enhancing labour reallocation) was ‘relatively small and short-lived,’ the total fiscal cost was $88.8 billion (of which $70 billion related to the first six months) making it one of the largest fiscal and labour market interventions in Australian history.

- Overall, ‘JobKeeper provided value for money through its broad social benefits and the role it played in addressing extraordinary and unquantifiable uncertainty and averting the worse economic tail risks of the pandemic.’

- It was ‘implemented with incredible speed and was well managed.’ Cross-agency collaboration was a strength of the program.

- There are lessons that could improve outcomes and value for money should a similar scheme be required in the future:

- A policy design that more readily adopted to changing conditions could lower costs.

- An earlier commitment to keep JobKeeper more closely aligned with the introduction of social distancing and other pandemic-related restrictions could have increased efficiency.

- A tiered payment structure or one proportionate to previous earning would be better targeted than a flat payment.

- Narrow eligibility and exclusions reduced JobKeeper’s effectiveness.

- Transparency requirements should be built into policy design to build public trust and enable scrutiny of public spending. JobKeeper was something of an international outlier in this regard.

- Clear communication from policymakers is critical. As is the availability of timely and granular data – and its analysis.

- Communication should emphasise uncertainty around cost estimates and be clear about assumptions.

- A policy like JobKeeper should only be considered where there is an exogenous and temporary shock with substantial economy wide implications – JobKeeper was a unique policy designed for an extraordinary situation.

- Peter Martin reports on the views of 50 leading Australian economists on the best government policies to support decarbonisation. An economy-wide cap and trade carbon price was the most popular option among survey respondents, followed by expediting the building of new transmission lines.

- Data on the pattern of individual giving in Australia. The overall trend is of a decrease in the share of taxpayers donating across genders, age brackets, income bands and states/territories.

- Outgoing Grattan Institute CEO and incoming Productivity Commission Chair Danielle Wood gave the Freebairn Lecture on Tax reform in Australia: an impossible dream? Wood’s speech asks ‘Why, after so many decades of discussion, so many points of broad economic consensus, does tax reform remain so challenging?’ Wood’s answer to this question cites a mix of vested interests (concentrated losers, diffuse winners, and weak institutional checks on influence, lobbying and political donations), media sensationalism (tax stories lend themselves particularly well to winners and losers narratives), the attractive politics of scare campaigns, and human psychology (salience matters – a one-time stamp duty might ‘feel’ worse than an annual land tax bill). Wood also offers four steps for reformers: (1) An external push is often needed to put tax reform on the agenda; (2) a reform package is better than incremental change, by sharing the costs more broadly and perhaps by offering some compensation to losers; (3) be prepared to campaign long and hard for the reform; (4) ensure that the reform sticks by creating positive feedback loops. (See also the Blinder link below.)

- The Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO)’s National fiscal outlook 2023-24. According to the PBO, the national fiscal outlook has improved since its October 2022 report, thanks to a stronger-than-expected recovery from COVID-19 and higher-than-expected commodity prices over 2022-23. The stronger budget balances that resulted have reduced net debt but changes in interest rates have lifted interest payments. The PBO also considers fiscal sustainability, concluding that ‘the national fiscal position is likely to remain sustainable, given prudent fiscal management, providing sufficient fiscal space to address key risks.’

- Douglas Irwin looks back at trade theory, trade policy, and the work of the late Max Corden.

- The Economist magazine considers what a third world war would mean for investors and runs through some alternative explanations as to why global markets don’t seem to be pricing in the risk of a major conflict: (1) they think the odds of such a disaster are pretty close to zero; or (2) they are about to be blindsided in the way that investors were in 1914; or (3) that even if investors did anticipate a major conflict, there would be little they could do to profit from it, given that war ‘involves a level of radical uncertainty far beyond the calculable risks to which most investors have become accustomed.’

- Also from the IMF, a new working paper looking at public support for climate change mitigation policies across 28 countries (including Australia).

- Content from the 22nd BIS Annual Conference on Central banks, macro-financial stability, and the future of the financial system.

- An FT collection of recent Martin Wolf pieces on the economic future of China.

- A theory of trade policy transitions.

- This new IMF working paper on geopolitical shocks and international trade finds that ‘the much-debated geopolitical alignment between countries has contradictory and statistically insignificant effects on trade, depending on the level of economic development. Moreover, the economic magnitude of this effect is not as important as income or geographic distance, and it diminishes significantly when extreme outliers are removed from the sample.’

- The 2023 Real East Bubble Risk index by global city.

- Alan Blinder discusses narrowing the gap between economics and politics. Relevant to the Wood speech linked above, Blinder offers an example of how he sees the difference between economic and political logic: consider a tax break that would reap $1 million in gains for each of ten people but cost 20 million people $1 apiece. According to Blinder, economic logic would count this as bad policy but political logic would view it differently – the 20 million losers of a dollar each probably won’t notice or at least be moved to political action by their loss, while the ten winners of $10 million will notice and be grateful – translating into gains for the politicians who delivered it (support, campaign contributions etc.). In Blinder’s view, this difference in logic explains why a range of decisions on tax policy, trade policy, regulation, and antitrust might seem obviously ‘wrong’ to economists, but would still not be corrected even if politicians somehow just ‘understood economics better.’ Blinder also argues that while political time horizons are typically too short for economists, economists’ time horizons are often too long for politics – people do not live in equilibrium states and ‘transition costs’ are not unimportant details.

- On the avocado and Mexican water wars.

- John Lanchester’s LRB essay on crypto corruption.

- Yasheng Huang on the exam that broke society.

- A New Statesman audio long read – John Gray on Israel, Hamas and the unravelling of the West.

- The BBC’s In Our Time podcast discussed Keynes’ 1919 book The Economic Consequences of the Peace.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content