Once again, economy watchers focused on the RBA this week. The minutes of the 7 November monetary policy meeting provided more detail on the decision to increase the target cash rate earlier this month, highlighting the importance of managing expectations and central bank credibility in the context of inflation that was now expected to be higher for longer. There was nothing here to fundamentally change the assessment delivered last week after reading the November 2023 Statement on Monetary Policy (SMP), although the minutes’ hawkish tone did reinforce the sense that Martin Place currently feels it has little room for manoeuvre on monetary policy.

Despite the recent run of good news on the international front – with inflation continuing to ease in the United States, the United Kingdom, the Eurozone and Canada – the RBA remains very cautious when it comes to the domestic inflation story.

That message was further reinforced in this week’s speech by Governor Bullock which emphasised that ‘the remaining inflation challenge…is increasingly homegrown and demand driven’, and warned that an ‘important implication of this homegrown and demand-driven component to inflation is that getting inflation back to target will take time.’ In this context, next Wednesday’s monthly inflation print for October will be a significant data point ahead of the 5 December RBA Board meeting.

It's worth remembering that this anticipated gradual disinflationary process will take place under a revised monetary policy framework from February next year, as Martin Place puts in place some of the recommendations from the recent Review into the Reserve Bank. Governor Bullock also used Wednesday’s speech to elaborate on some of the details. More on those details below.

Finally, please note that the Weekly will take a short break next week but will be back on 8 December with an update on the last RBA meeting of 2023.

RBA minutes’ hawkish tone

The minutes from the 7 November 2023 Monetary Policy Meeting of the Reserve Bank Board provided some further context to the central bank’s decision to increase the cash rate target earlier this month. Once again, the RBA Board found itself debating the relative merits of leaving policy unchanged for what would have been a fifth consecutive month versus delivering a 25bp increase. That debate also took place in the context of new RBA forecasts for the economy (see last week’s note for a detailed look) which projected that inflation would only return to the top of the inflation target range in late 2025, and which were further predicated on an additional one or two increases in the cash rate as well as an assumption that productivity growth would return to trend.

According to the minutes:

‘The case to hold the cash rate constant at this meeting was premised on the argument that inflation was continuing to decline in year-ended terms, the economy was slowing, and the geopolitical and economic outlook was highly uncertain. In that environment, there was a case to wait for additional information before determining whether a further adjustment to the cash rate was required.’

That is, combine significant uncertainties around the potential economic and financial implications of the crisis in the Middle East with surging population growth at home in Australia, which members said ‘was making it more challenging to assess the underlying resilience of the economy’ and add in ‘the acknowledgement that inflation expectations remained broadly anchored’ and you could construct ‘a credible case that a somewhat slower return of inflation to target did not warrant a policy response at this meeting.’

But set against these arguments was the alternative view:

‘The case to raise the cash rate target by a further 25 basis points centred on the risks arising from the outlook for inflation being stronger than it had been some months earlier…underlying inflation in the September quarter had been higher than previously expected, inflationary pressures were evident across a broad range of consumer items, and inflation was most apparent in items for which inflation typically took longer to subside (such as services)…these observations implied that it would take some time for inflation to return to target.’

In addition to the increased risk of inflation failing to return to target by end-2025, the minutes cited a ‘greater-than-expected resilience of domestic demand’ meaning it would take longer to bring supply and demand back into balance give that further disinflation was likely to require continued subdued activity. They also reported some concerns around ‘a slight upward drift in some financial market measures of inflation expectations’ and ‘growing signs of a mindset among businesses that any cost increases could be passed onto consumers.’

The commentary also made the same argument advanced in our own assessments prior to the 9 November meeting regarding RBA credibility. That is, members ‘agreed there was a risk of inflation expectations increasing if the Board left the cash rate target unchanged at this meeting, particularly given the Board’s repeated statements that it has a low tolerance for inflation returning to target after 2025.’ [emphasis added]

And as we know, the board decided that this second set of arguments was stronger and tightened policy accordingly.

Other points of note from this week’s minutes included:

- The RBA saw the potential for upside inflation surprises arising from any disruption to energy supplies from the Middle East, and from El Nino effects on global food price inflation.

- The pace of population growth – due to a faster-than-expected return of students and international visitors – has added strongly to spending. But because this has lifted both supply and demand, in the aggregate the RBA judged the net effects on inflation were ‘largely offsetting’ although it also cautioned this may have varied across sectors (think of the housing sector and rental inflation).

- The rise in real longer term bond yields in advanced economies (perhaps due to some combination of higher estimates of neutral rates due to persistent inflation and higher term premia due to more uncertainty about future inflation and interest rates) implied that there was some tightening in monetary conditions underway independent of changes in official policy rates. But the minutes reckoned that this was less significant in Australia than in the United States, given the relatively lower importance of bond markets for our corporate financing.

- Required mortgage payments as a share of household disposable income had risen to a record high of around ten per cent by the September quarter 2023, although overall debt service costs were still below their previous peaks due to households having reduced their total stock of personal debt.

- Finally, the minutes reported that a larger-than-usual share of borrowers had been drawing down funds in their offset accounts, consistent with consumers finding it harder to finance expenditure out of current incomes. Still, according to the RBA, this share had not risen over prior months and banks had not reported a significant rise in the proportion of households experiencing difficulties making their mortgage payments.

RBA Governor focused on homegrown, demand-driven inflation

RBA Governor Michele Bullock hit two themes in her speech to the Australian Business Economists this week. One of these (discussed later) covered changes to the central bank’s monetary policy processes in response to the recent Review into the RBA. But she also used her time to reinforce the message that the RBA is determined to bring inflation back to target, and that in its view ‘the remaining inflation challenge we are dealing with is increasingly homegrown and demand driven.’

That emphasis on the domestic drivers of inflation is important in a context where the recent international news on inflation has been positive, because it implies that rather than simply wait for an ongoing correction in supply conditions to bring down inflationary pressures, ‘a more substantial monetary policy tightening is the right response to inflation that results from aggregate demand exceeding the economy’s potential to meet that demand.’

The governor’s speech cited three pieces of evidence in support of her argument that Australia has experienced a shift ‘from mainly supply-driven to mainly demand-driven inflation.’

First, inflation looks broadly based. According to the RBA, around two-thirds of the items in the CPI basked still have inflation running above the target band. And underlying (trimmed mean) inflation has been higher than the central bank expected.

Second, inflation seems to be increasingly underpinned by strong rises in services prices. In part, this reflects the strength of domestic demand relative to supply. And in part it reflects domestic cost pressures from labour, energy, business rents and insurance. In contrast, imported cost pressures are easing.

Third, the economy has only limited spare capacity. The RBA thinks this is most evident in the labour market, where it highlights the low (hours-based) labour underutilisation rate.

Bullock also warned that one ‘important implication of this homegrown and demand-driven component to inflation is that getting inflation back to target will take time.’ So, while it took just three quarters for inflation to fall from almost eight per cent to 5.5 per cent due to easing supply constraints, the RBA expects it to take ‘another two years for inflation to fall that much again and move below 3 per cent.’

Australia’s monetary policy framework will be adjusted next year

Governor Bullock also used her speech this week to talk about the upcoming changes to Australia’s monetary policy framework. The RBA has already committed to a range of changes as it implements some of the recommendations from the Review of the Reserve Bank of Australia. These include:

- A reduction in the number of Board meetings to eight a year.

- Longer Board meetings, spanning two days.

- An internal staff meeting at the beginning of the Board cycle that Board members would be able to attend.

- Board oversight of the research agenda

- Changes to the central bank’s communications, including the post-meeting statement being issued by the Board, rather than the Governor, and media conferences after each meeting.

The new schedule of meetings starts on 5-6 February next year, with the policy decision to be announced at 2.30pm on the second day, followed by a media conference at 3.30pm.

Bullock elaborated on some of these adjustments and provided some additional details including: plans to change the look and feel of the quarterly Statement on Monetary Policy (which will now be released at the same time as the monetary policy decision every second meeting); modifications in the materials to be provided to the Board in order to offer a more strategic focus, with ‘a greater role for scenario analysis to facilitate a discussion of risks to the outlook and the potential implications of different decisions…[and]…a deeper discussion of trade-offs and a consideration of how the immediate decision fits within the medium-term strategy.’; and a commitment to providing the Board with a summary of staff views, including material ‘setting out in more detail the arguments raised by staff for and against particular policy options and strategies.’

The governor also said the central bank would be working on culture and leadership, including by ‘encouraging more active debate and challenge’ than was previously the case.

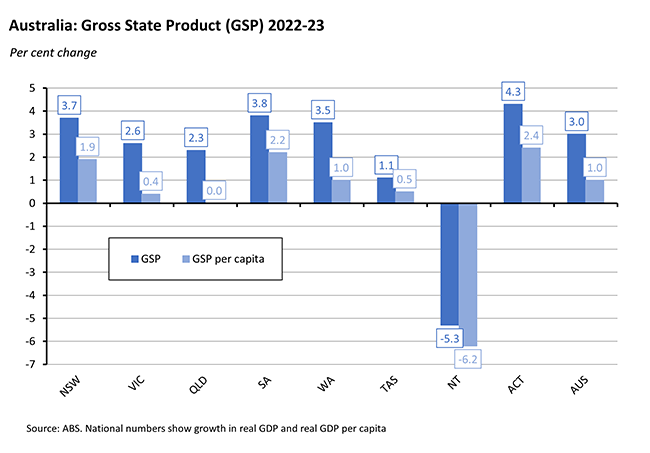

The ACT was the fastest growing of Australia’s states and territories in 2022-23

The ABS said that all states and territories enjoyed a rise in Gross State Product (GSP) in 2022-23 except the Northern Territory. The Australian Capital Territory (ACT) enjoyed the fastest growth in GSP at 4.3 per cent, followed by South Australia (3.8 per cent) and New South Wales (3.7 per cent).

The ACT also saw the fastest growth in GSP per capita (2.4 per cent) followed by South Australia (2.2 per cent).

What else happened on the Australian data front this week?

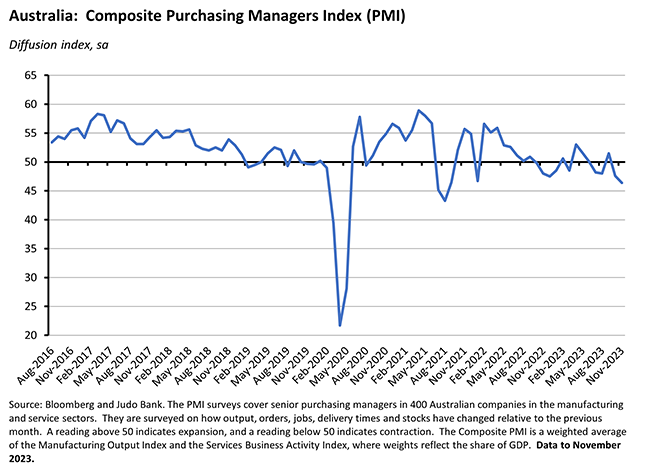

The Judo Bank Flash Australia Composite PMI Output Index slipped to 46.4 in November 2023 from 47.6 in October, falling to a 27-month low. The Flash Services PMI Business Activity Index fell to 46.3 from 47.9 (a 26-month low). The Flash Australia Manufacturing PMI Output Index rose to a 2-month high of 47.2, up from 45.8 in October but the Flash Australia Manufacturing PMI fell from 48.2 in October to 47.7 in November, a 42-month low.

November marked a second successive month of declining business activity, with this month’s reduction the quickest since August 2021. According to Judo Bank, the downturn in the PMI came ‘amidst widespread reports of softening economic conditions and high interest rates negatively affecting budgets.’ At the same time, there was also a rise in inflationary pressures, with higher wages and fuel costs pushing up both input cost and output price inflation. That combination of higher inflation, weaker demand and high interest rates saw the measure of business confidence fall in November to the lowest recorded in the history of the series (since May 2016)

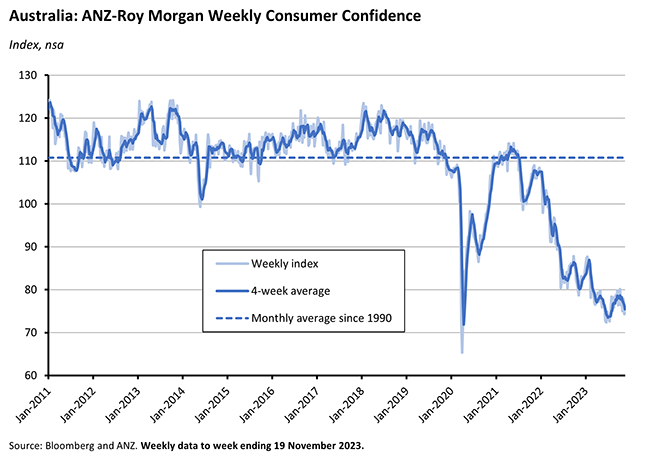

The ANZ Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence Index rose by a modest 0.4 percentage points over the week ending 19 November 2023. Despite the slight increase, at a level of just 74.7, the index continues to signal significant weakness in sentiment. Weekly inflation expectations edged up 0.1 percentage points to 5.6 per cent.

The ABS said that its experimental monthly employee earnings indicator rose 3.8 per cent over the month to September 2023 (calendar-day adjusted basis) to show wages and salaries paid by employers up 8.4 per cent over the year. The monthly growth rate was up from 1.6 per cent in August which the ABS said reflected businesses paying cyclical bonuses in September. (The monthly indicator captures the combined impact of underlying wage growth, increased employment, and changes in hours worked and periodic payments.)

Other things to note . . .

- In the AFR, Paul Bloxham asks, is there really a path to soft landing for the RBA and the Australian economy?

- Meanwhile, Peter Martin thinks lower inflation outcomes in the US and UK mean the RBA is less likely to increase rates.

- Treasury has published a consultation paper on merger reform.

- Related, an e61 Institute report (from August this year) on the competitive impact of stealth M&A in Australia.

- CoreLogic lists five things to know about migration and the Australian housing market.

- An RBA speech on changes in Australian securitisation markets.

- Data from the ABS on Australian patient experiences in 2022-23. About 82 per cent of Australians saw a GP in 2022-23 while 52 per cent saw a dental professional. Around 58 per cent of people aged 15 or over had private health insurance.

- This week’s Economist magazine has a briefing on how war and crises are piling up so much that the capacity of diplomats, generals and leaders is being stretched to its limits.

- Also from this week’s edition, the magazine’s The World Ahead 2024 which argues that next year will be a stressful one for liberal democracy.

- The WSJ analyses the US$2 trillion interest bill that’s hitting governments. Faced with higher military spending, rising climate-related expenditures and demographically driven budget pressures, the rising burden of debt service is presenting fiscal authorities with uncomfortable choices.

- IMF staff deliver a stocktake of global climate mitigation. Their message is that to meet the Paris Agreement ambition of limiting global warming to 1.5C, countries will need to close both a large ambition gap and a sizeable policy implementation gap. On the former, the Fund says global policy ambitions would need to be more than quadrupled from existing levels, since while current targets would cut 2030 greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to 11 per below their 2019 levels, that falls well short of the cuts of 50 per cent that would be required to achieve 1.5C. On the latter, the paper says that in a business-as-usual scenario, global GHG emissions are on track to rise four per cent by 2030. It estimates that measures equivalent to a global carbon price of at least US$85 would be need just to get emissions on track for 2C, and an even higher price would be required for 1.5C. By way of comparison, the current global weighted average carbon price is just US$5.

- Related, the OECD climate action monitor 2023 reports that national climate policy action across the countries that together account for nearly two thirds of total GHG emissions only increased by one per cent in 2022. That was the lowest annual growth recorded since 2000, which the OECD attributes in part to a focus on energy security.

- Also from the OECD, Corporate Tax Statistics 2023 and an accompanying working paper on the effective tax rates of large multinational enterprises.

- Three interesting pieces from the FT: Martin Wolf warns of the looming threat of fiscal crises, Ruchir Sharma says China’s rise is reversing, pointing out that China’s share of world GDP (when measured in nominal US dollar terms) is set to fall for a second consecutive year in 2023, and Soumaya Keynes sums up what we’ve learned about ‘greedflation.’

- A new BIS Financial Stability Institute Paper on climate change and avoiding the insurability tipping point. The authors caution that insurers’ approach to underwriting and pricing climate-related risks could have negative implications for financial stability either because under-pricing and overly optimistic underwriting could lead to solvency or liquidity problems for insurers or because mass withdrawals of coverage from economically significant sectors could cause disorderly economic dislocations. A survey of insurers finds that while most of those surveyed currently do not explicitly account for climate change impacts when pricing insurance policies, there is a noticeable trend of increasing premia and falling coverage. Risings insurance costs reflect in part the increasing frequency and severity of the insured risks as well as increased exposure from the concentration of assets in high-risk regions.

- On the green transition and geopolitical tensions.

- From Brad DeLong: The Google antitrust trial sends the attention economy to court.

- Also from DeLong, two short book reviews consider the US financial system that was reformed by Roosevelt’s New Deal and its state today.

- Charting the relationship between working hours and average pay across the OECD.

- How supply shocks (and dual mandates) lead to disagreements over monetary policy.

- A piece from RAND asking how AI might affect the rise and fall of nations.

- A new working paper on the short-term effects of generative AI on employment finds that the release of ChatGPT had negative effects on the employment and earnings of online freelancers, implying a reduction in demand for knowledge workers. The authors also find ‘suggestive’ evidence that the top freelancers were disproportionately affected by AI.

- Noah Smith notes the current upswing in US productivity growth and says the roaring 20s are back on track. (Interestingly, one of the several explanations Smith considers for the recovery in US productivity is a lift from WFH. Compare and contrast that with the Bloxham piece linked above, which speculates that one potential cause of Australia’s recent poor productivity performance might be…WFH. Granted, both arguments could be true if we assume that US managers are implementing flexible working arrangements much more effectively than their Australian counterparts. Alternatively, we could take this as suggesting that nobody really knows for sure what drives productivity…).

- The Rhodes Center podcast in conversation with Angus Deaton.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content