The international economic news this week has been dominated by developments in Ukraine, as events in Eastern Europe have roiled global financial and commodity markets. Rising energy prices and sliding share markets have arrived at a time when policymakers were already fretting about inflation and supply-side disruptions.

Now geopolitics is adding to the pressure on central banks who find themselves having to navigate increasingly treacherous waters. In economic terms, the downside risk for the global economy is for more inflation, higher interest rates, tighter financial conditions and slower growth. Of course, there are issues that go well beyond economics and finance here, and much will depend on how events in Europe play out.

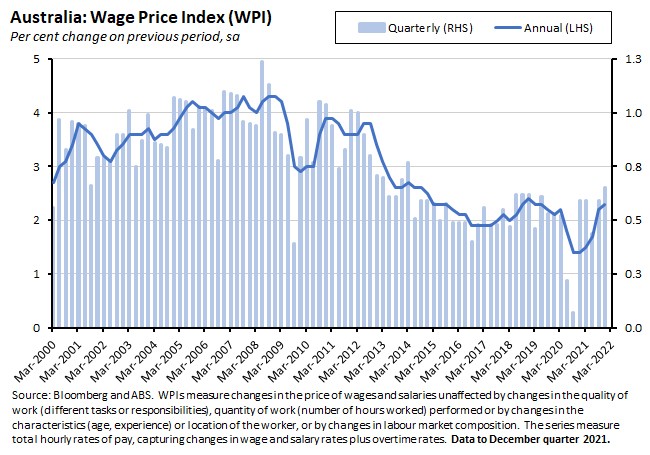

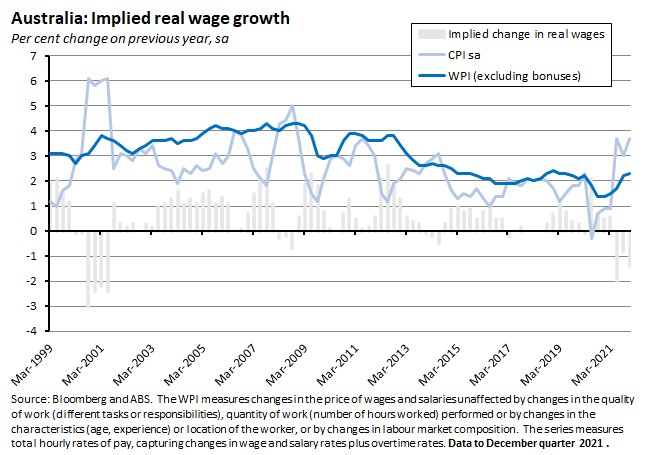

Here in Australia, the key economic event this week was the release of the December quarter 2021 wage data, with the ABS reporting that the Wage Price Index (WPI) rose by 0.7 per cent over the quarter to be up 2.3 per cent over the year. That was the fastest quarterly growth rate recorded since 2014 and the fastest annual growth since 2019. As such, it indicates that a tightening labour market is having an appreciable impact on wage growth. But with the RBA judging that wage growth above three per cent will be required for inflation to be sustainably in the central bank’s target range, the December quarter outcome on its own provides little ammunition for those arguing for earlier and aggressive rate hikes than currently contemplated at Martin Place.

This week’s note also takes a quick look at other Australian data including Flash PMIs for February and construction work done and private capex for the final quarter of last year. There is also the usual roundup of selected links, including a critique of the LMITO, Australia’s missing foreign policy debate, a (pre-Ukraine) update on the global economy from the IMF, the latest Munich Security Report, a look back at how the US Fed prevented a financial meltdown at the start of the pandemic, the return of monetarism and why central banks can’t forecast commodity prices.

Next week is a big one on the Australian economic front, with the March RBA meeting on Tuesday and the release of December 2021 quarter GDP on Wednesday. Due to a coincidence of timing, however, I’m away from home and office next week, attending the AICD’s AGS 2022 in Melbourne. Unfortunately, that also means that there will be no weekly note. But it will give me the chance to say hello to readers in person.

My apologies to readers for missing such an important week on the data calendar, but I’ll aim to cover the main highlights in the following week’s note.

Ukraine, energy prices, and inflation risks compound to test policymakers and markets

At the time of writing (on Thursday evening), events in the Ukraine this week had seen Moscow first recognise the breakaway Republics of Donetsk and Luhansk in the Donbas region and send in Russian troops as ‘peacekeepers’, then threaten to extend the Republics’ territory to what were Ukrainian-controlled parts of Donbas, followed by announcing that the leaders of the two separatist regions had requested the use of Russian military force, and – shortly before hitting ‘send’ on this copy – launched an invasion of Ukraine. Russia’s moves had initially seen Western countries impose what now looks likely to be just the first in a wave of sanctions against Moscow: The United States said that it would target selected Russian financial institutions, the Russian sovereign debt market and the company behind the Nord Stream 2 natural gas pipeline; Germany declared that it would halt certification of Nord Stream 2; the UK introduced its own round of modest financial sanctions; and the EU sanctioned senior Russian figures. As the security situation continues to worsen, the intensity of sanctions is set to increase in parallel. That in turn could prompt Moscow to implement some of its threats around the ‘weaponisation’ of commodity supplies.

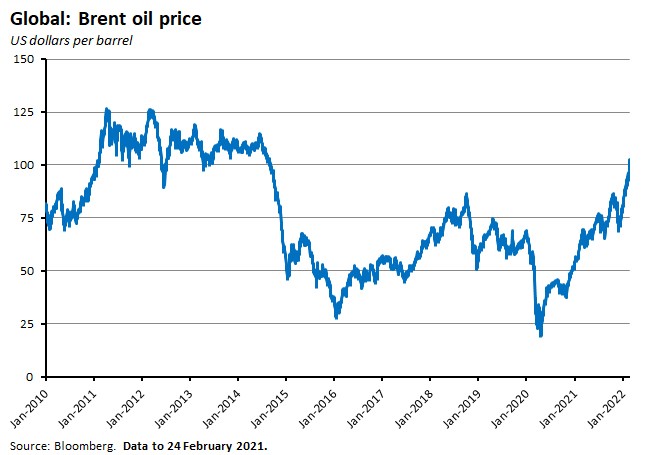

The financial impact of recent developments has already been felt in rising energy prices and falling share markets. Russia is one of the world’s largest gas and oil exporters (as of last year Russia was the world’s third largest oil producer, accounting for about 10 per cent of global output or about 10 million barrels of oil per day). It supplies Europe with about 40 per cent of its gas supply and around 25 per cent of its oil. Spot gas prices are already at record levels in Europe and Asia and oil prices had been pushed up to US$100/barrel as tensions have risen – jumping above US$100/barrel on news of the invasion.

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify

The disruption to global energy markets and the consequent increase in prices comes at a time when many Western policymakers were already focussed on inflationary pressures and their political masters were worried about the rising cost of living. Higher energy prices will, of course, further exacerbate both challenges, raising the spectre of a stagflationary shock in the form of a nasty combination of rising prices, falling confidence, squeezed consumer incomes and compromised supply chains that pushes up inflation while sapping economic growth.

The disruption could go also beyond oil and gas: Russia is a key global supplier of wheat, as is Ukraine (US wheat futures jumped to a ten-year high on Wednesday on fears of supply disruption) and of other food products and fertilizers, as well as a major exporter of a range of metals including aluminium, nickel, copper, palladium and vanadium (aluminium and nickel prices hit multi-year highs this week while palladium prices hit a six-month high).

These and related concerns will also take a toll on overall financial market sentiment. As Russia’s first moves in the Ukraine played out this week, one immediate response was a sharp fall in Moscow’s Moex Index. That has been followed by declines across global stock markets along with a rise in market volatility. Optimists have been arguing that (1) markets were already pricing in significant geopolitical risk before this week’s developments, limiting the scope for further big adjustments and that (2) many previous geopolitical shocks have anyway had only short-lived impacts on market valuations. But those arguments need to be balanced against the backdrop of central banks that were already under significant pressure to normalise monetary policy settings in the face of rising prices and that may therefore be less willing to prop up market sentiment than would otherwise be the case, and that also have limited room for manoeuvre should more stimulus be required. It’s also important to note that we also still don’t know what the end game will look like, which will have a significant impact on the ultimate implications of this unfolding geopolitical shock.

Australian wage growth picks up, but not by enough to move the RBA

The ABS said that in the December quarter of last year the Wage Price Index (WPI) rose 0.7 per cent over the quarter (seasonally adjusted) to be up 2.3 per cent over the year. That was the fastest pace of annual growth seen since the June quarter of 2019 and the strongest quarterly growth since the March quarter of 2014. But it was also well below the kind of wage growth ‘with a three in front of it’ that the RBA has said it thinks is necessary to deliver an inflation rate that is sustainably within its two-three per cent target band.

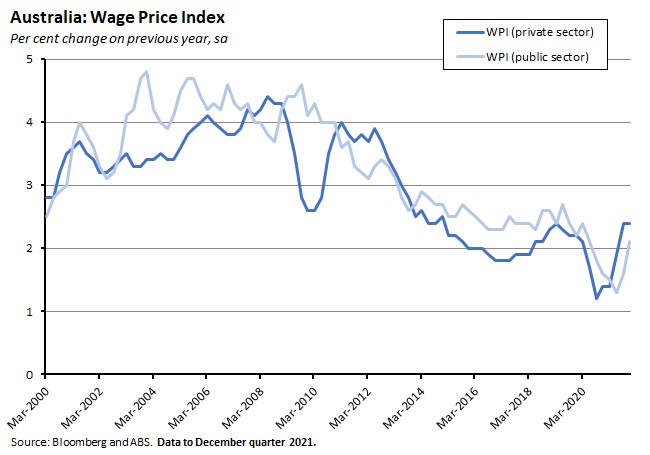

Both private and public sector WPIs rose 0.7 per cent over the December quarter, with private sector wages rising at an annual rate of 2.4 per cent and public sector wages up 2.1 per cent.

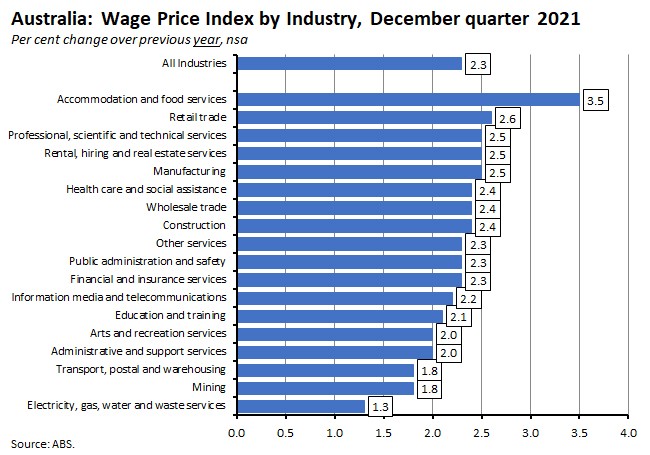

By industry, quarterly wage growth (in original terms) was fastest in retail trade (up 1.2 per cent over the quarter in the strongest result for the sector since the September quarter 2015), information, media and telecommunications (up 1.1 per cent) and accommodation and food services (up one per cent). These were the only three industries to report quarterly growth of one per cent or more, however, down from five industries in the September quarter.

In annual terms, accommodation and food services was the only industry to record wage growth with a three in front of it, with a strong 3.5 per cent growth rate which the ABS noted was boosted by the payment of both the 2020 and 2021 Fair Work Commission annual wage increase in the March and December quarters of this year. Only one other industry – retail trade – recorded an annual increase in excess of 2.5 per cent.

The ABS did note that the ‘proportion of pay rises reported over the December quarter was higher than usually seen at this time of year’ reflecting the ‘implementation of the last phases of award updates and state-based public sector enterprise agreements, on top of a rising number of wage and salary reviews’. And the Bureau also reported that ‘wage pressure continued to build over the December quarter for jobs with specific skills. Private sector wage growth occurred across a broad range of industries as businesses looked to retain experienced staff and attract new staff.’

The December quarter WPI therefore does show that a recovering labour market in general and rising labour demand in particular are now translating into stronger wage growth. That said, the actual result was roughly in line with RBA forecasts (which had anticipated an annual 2.25 per cent WPI print) and does not show any real sign of a rapid breakout in wage pressures. In the context of a pre-pandemic average rate of growth for the WPI of 0.8 per cent in quarterly terms and 3.2 per cent in annual terms, this was not a particularly dramatic result. Rather, it marks more of a return to pre-pandemic norms. Granted, if the labour market continues to tighten there’s certainly scope for wage growth to accelerate from here. Still, taken on its own, it’s hard to see this particular data drop warranting a significant rethink on the part of the RBA when it comes to its stated ‘patient’ approach to monetary policy normalisation.

Finally, note that with annual wage increases running at 2.3 per cent and annual inflation at 3.5 per cent (or 3.7 per cent on a seasonally adjusted basis), real wage growth was once again negative in the December quarter.

What else happened on the Australian data front this week?

IHS Markit Flash PMIs

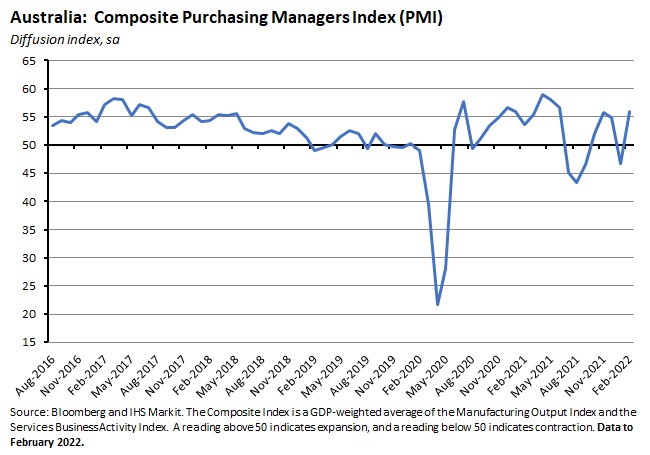

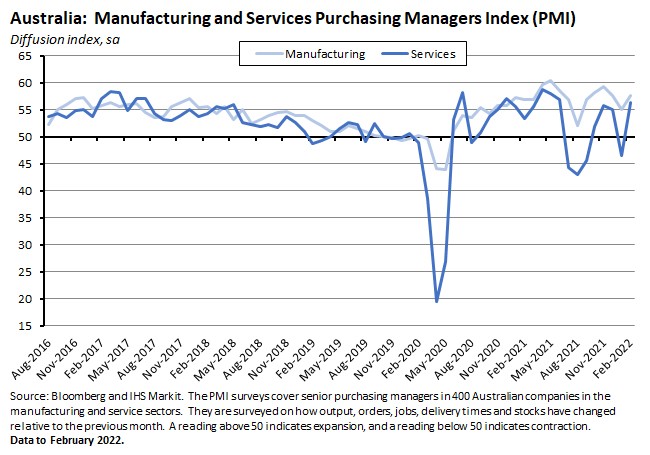

The IHS Markit Flash Australia Composite PMI (pdf) rebounded into positive territory in February this year. After having fallen into contractionary territory with a reading of 46.7 in January the index rose to 55.9 this month, reaching an eight-month high.

The Flash Australia Services Business Activity Index rose from 46.6 in January to 56.4 in February (another eight-month high) while the Flash Manufacturing PMI rose from 55.1 in January to 57.6 in February (a two-month high).

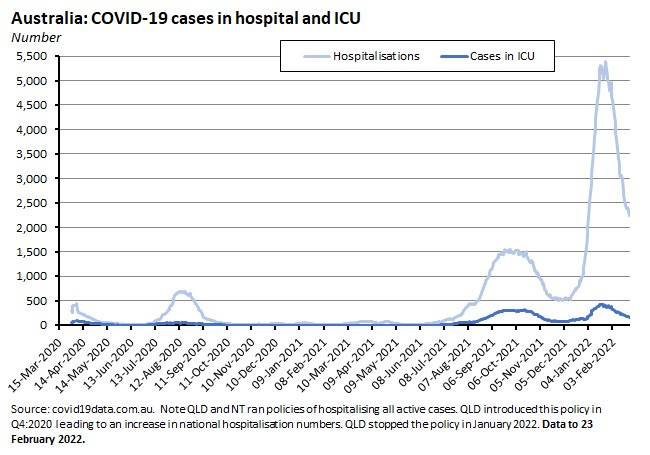

The February PMI shows that business activity – particularly in services – has bounced back quite strongly from January’s Omicron-induced slide as case numbers, hospitalisations and ICU admissions have all trended lower into February.

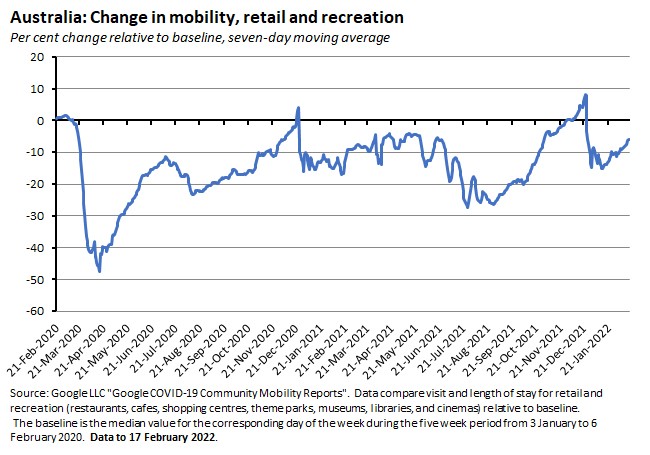

The improved PMI readings, especially for services, are also consistent with an uptick in mobility indicators over the past couple of weeks.

In less welcome news, the PMI surveys continued to report problems on the supply side of the economy: according to respondents, shortages of materials and labour are still impeding private production, input prices continue to rise (albeit at a slower rate than in January), and output price inflation hit a new record this month.

ABS private capital expenditure

According to the ABS, total new capital expenditure rose 1.1 per cent over the December 2021 quarter (seasonally adjusted) to be 9.8 per cent higher over the year. Spending on buildings and structures rose 2.2 per cent in quarterly terms and 11.2 per cent in annual terms, while spending on equipment, plant and machinery slipped 0.1 per cent over the quarter but was still up 8.4 per cent relative to the December 2020 quarter.

In terms of expected capital expenditure, Estimate 5 for 2021-22 was $140.8 billion, up 1.6 per cent from Estimate 4 for the same year. Looking further ahead, Estimate 1 for 2022-23 was $116.7 billion, which is 10.8 per cent larger than Estimate 1 for 2021-22. That’s a strong first result for investment intentions in 2022-23, suggesting that firms are responding to strong growth with projected increases in capacity, and that investment plans haven’t been too hurt by uncertainty about future conditions.

ABS construction work done

The ABS said that the value of total construction work done in the December 2021 quarter fell 0.4 per cent over the previous quarter (seasonally adjusted) but was up 2.9 per cent over the year. The value of building work done fell 1.3 per cent over the quarter but was up two per cent in annual terms, while engineering work done rose 0.7 per cent quarter-on-quarter and 4.2 per cent year-on-year. The quarterly decline in building work was driven by a drop in residential construction (down 2.9 per cent over the quarter) but non-residential construction was 1.3 per cent higher relative to the September quarter.

ANZ-Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence

The ANZ-Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence Index fell 1.4 per cent last week, with a large drop in New South Wales (down 5.6 per cent), a sizeable fall in Western Australia (down 2.8 per cent) and more modest declines in Queensland (down 0.8 per cent) and South Australia (down 0.7 percent). At a level of 101.8, the confidence index remains below its long-run average of 112.4. Confidence was up 2.9 per cent in Victoria.

Weekly inflation expectations rose 0.1ppt to 5.1 per cent last week, their highest result since December 2014, likely reflecting the impact of the record high petrol prices seen over recent weeks. These rising inflation expectations and cost of living pressures more generally may well be contributing to softer consumer confidence readings.

ABS monthly household spending indicator

This week saw the ABS publish a new, experimental indicator of household spending derived from aggregated and de-identified card and bank transactions data. Household consumption accounts for about 50 per cent of Australian GDP and the Bureau reckons that the new indicator covers about 68 per cent of household consumption. That’s more than twice the coverage of the current monthly retail trade survey, which is only around 30 per cent.

The first release showed current price household spending up 3.1 per cent over the month and 8.6 per cent over the year to December 2021. The largest annual spending increases were on furnishings and household equipment (up 27.4 per cent) and hotels, cafes and restaurants (up 23.6 per cent), while spending on recreation and culture fell 8.9 per cent over the year.

ABS Average weekly earnings

The latest ABS estimate for average weekly ordinary time earnings for full-time adults as of November 2021 was $1,748.40. That was a 2.1 per cent ($37) increase from the November 2020 estimate. Full-time adult average weekly total earnings were $1,812.70, a 2.4 per cent increase.

Other things to note . . .

- Peter Martin is not a fan of the Low and Middle Income Tax Offset (LMITO).

- Grattan makes the case for a ‘shared equity’ scheme to mitigate Australia’s housing affordability challenge (under the plan, the federal government would co-purchase up to 30 per cent of the home value – including the rights to 30 per cent of any subsequent capital gain when sold – for a selected number of low-income Australians).

- The Australia in the World podcast offers a take on the Australian foreign policy election debate we should have, but almost certainly won’t.

- The IMF’s G-20 Surveillance Note, prepared for the 17-18 February 2022 G20 Finance Ministers Meetings says that the pace of the global economic recovery has slowed, as economic indicators since the January 2022 World Economic Outlook Update ‘point to continued weak growth momentum amid the spread of the virus’ and adds that ‘Supply-demand mismatches, increases in energy and food prices, and bottlenecks in transportation of goods have put upward pressure on inflation’. It cautions that downside risks predominate due to ongoing uncertainty around the evolution of the pandemic, inflation, and the high public and private sector debt levels that expose emerging markets in particular to tighter global financial conditions. The Fund also cautions that implementing ‘the first best policy mix will be particularly challenging amid difficult trade-offs between containing inflation and supporting the recovery.’

- Also from the IMF, a Working Paper on China’s declining business dynamism.

- The ECB on the eurozone’s natural gas dependence and risks to activity.

- The Munich Security Report 2022. The theme is the emergence of a sense of ‘collective helplessness’ in the face of a rising tide of reinforcing global challenges: the pandemic, climate change, increasing geopolitical tensions and the vulnerabilities of an interconnected world are together creating ‘stressed and overburdened societies.’

- Tracking the changing views on the relationship between international trade and inequality.

- Assessing the predictive accuracy of COVID-19 mortality projections. In the short-term (one-week ahead), a simple fitted second-order polynomial function does a better job than the forecasters, but the latter become more competitive at longer (three-four week) time horizon. And an ensemble forecast tends to perform well, suggesting that policymakers should avoid relying on just one forecasting team.

- This WSJ Essay looks back to March 2020 and how the US Fed averted economic disaster. Unparalleled emergency-lending backstops ‘helped to save the economy from going into a pandemic-induced tailspin’ and arrested a financial market meltdown. While successful, the case for speed meant ignoring any qualms over moral hazard, something critics fear will store up future problems.

- The FT’s Martin Wolf says that when it comes to inflation, economists should start taking the money supply seriously again.

- Interesting Bloomberg opinion piece arguing that central bank are getting their inflation predictions wrong because they can’t forecast commodity markets. Relying on futures prices, as many do, doesn’t work well as – despite what theory says – in practice the futures curve has not been a good guide to future spot prices. And current conditions mean that forecasting commodity markets – and inflation – ‘has become more art than science. What would be the Saudi king’s response to US pressure to boost oil production? What’s Vladimir Putin going to do with Europe’s gas supply? How will Beijing react to record high coal prices?’ Such questions, the piece argues, are likely to be ‘beyond the expertise of any central banker.’

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content