According to the IMF, the global economy is ‘limping along’. The Fund’s new forecasts for the world economic outlook suggest that near-term risks have subsided a little since earlier this year (although they do remain tilted to the downside) and that the chances of pulling off a soft landing have increased. Unfortunately, there is a risk that the IMF’s latest projections may already be out of date. They were pulled together before the recent turmoil in Israel and Gaza, with the Fund’s Chief Economist noting earlier this week that ‘it’s too early to really assess what the impact might be.

Further adding to the sense of whiplash in international economic matters, this week’s geopolitical shock arrived hard on the heels of last week’s financial shock in the form of a US Treasury market rout that saw yields on benchmark 10-year US Treasuries hit 16-year highs and prompted a sell off across other government bond markets. Explanations for the market turbulence included investors pricing in ‘higher for longer’ US Fed policy rates, concerns about the apparently ever-growing borrowing needs of the US government, fears about the credibility and stability of long-term US policymaking exacerbated by the first ousting of the Speaker of the US House of Representatives in US history and a more general rise in the term premium, with the breadth of options suggesting that nobody was quite sure what had just happened.

For now, initial economic concerns relating to this week’s violent conflict in the Middle East have focussed on the potential implications for oil prices which first rose quite sharply but which had fallen back at the time of writing as markets judged that the near-term implications for oil supply were limited. If there were to be any widening of the conflict, however, oil market related concerns would quickly return to front of mind.

It has been a dramatic few weeks for oil markets. Prior to the bond market meltdown, in late September analysts had been speculating that Saudi- and Russian-led production cuts under the auspices of OPEC+ could see oil prices return to US$100pb, threatening central banks’ disinflationary ambitions and (perhaps) necessitating higher policy rates in response. The bond market mayhem at the start of this month then sent oil prices tumbling as growth expectations – and estimates for future oil demand – were abruptly downgraded. At the start of this week, prices rose again, albeit to levels still well below their late September levels.

Meanwhile, the conflict is likely to have consequences for regional risk premia and for the overall level of economic uncertainty in the world economy. Further, to the extent that recent events are taken as further evidence of the crumbling of the Pax Americana, they could also prompt a broader rise in market assessments of and pricing for – geopolitical risk.

In last week’s webinar and presentations, I suggested that one way to think about the current position of the world economy was to see it as in ‘mid-transition.’ Not just in mid-energy transition (that is, caught between renewable and fossil fuel energy systems) but in mid-geopolitical transition (between the end of the US-led post-Cold War order and its still-to-emerge successor), as well as mid-demographic transition and mid-economic transition (where the latter particularly refers to the inflation and interest rate nexus). One implication of that worldview, I proposed, was more volatility, more disruption and more uncertainty. To some extent, this week’s events might be one tragic example of the perils of a global order in mid-transition.

After a review of the IMF’s new forecasts along with a look at the latest Australian data on consumer and business sentiment, this week’s note also discusses the latest RBA Financial Stability Review which included a deep dive on household financial resilience and summarises a new overview from Martin Place on how the various ways that the 400bp of monetary policy tightening delivered since May 2022 have influenced the Australian economy.

IMF: Short-term outlook slightly less risky, longer-term prospects mediocre

The October 2023 edition of the IMF’s World Economic Outlook (WEO) predicts that global economic growth will slow from 3.5 per cent last year to three per cent this year and to 2.9 per cent in 2024 on an annual average basis. Those headline numbers are little changed from the July 2023 WEO Update, with no change to the 2023 forecast and a modest 0.1 percentage point downgrade to the outlook for 2024. Sitting behind those aggregates, however, are some significant adjustments. The Fund is now considerably more optimistic about US growth, with upgrades of 0.3 percentage points (to 2.1 per cent) and 0.5 percentage points (to 1.5 per cent) for this year and next. The upgrades reflect stronger business investment, resilient consumption (due to a still-tight labour market) and an expansionary fiscal stance. Offsetting that, the IMF has cut its growth forecasts for the Euro Area and for China (in each case, by 0.2 percentage points this year and 0.3 percentage points in 2024). The Fund notes that China’s downgrades reflect the crisis in the property market and a lower rate of investment in response. For Australia, relative to the April 2023 WEO, the IMF thinks growth will be about 0.2 percentage points higher this year (at 1.8 per cent) and 0.5 percentage points lower next year (at 1.2 per cent).

In terms of global inflation, the WEO reports that the headline rate has more than halved and that about 80 per cent of the gap between 2022’s peak inflation rate and the pre-pandemic annual average of 3.5 per cent has now closed. Much of the disinflation work has been done by falls in energy prices and (to a lesser extent) in food prices, and as a result, the decline in underlying or core inflation has been more gradual. In this case, the WEO puts the global rate at almost two-thirds of the way back to the pre-pandemic average. Looking ahead, the IMF sees world consumer price inflation falling from 8.7 per cent last year to 6.9 per cent this year and 5.8 per cent in 2024. That is a shallower disinflation path than had been anticipated in the July WEO update, with inflation now predicted 0.1 percentage point higher this year and 0.6 percentage points higher in 2024.

While the numbers have not changed much, the tone of the IMF’s commentary has become somewhat more positive. The Fund’s chief economist reckons that its new projections ‘are increasingly consistent with a soft landing scenario, bringing inflation down without a major downturn in activity.’ Likewise, the WEO says that adverse risks ‘have receded since the April 2023 WEO, implying a more balanced distribution of risks around the outlook for global growth.’ The potential for surprises to the upside include the possibility that underlying inflation falls more swiftly than expected (allowing central banks to ease monetary policy sooner) and that domestic demand recovers faster (due to some combination of tighter than foreseen labour markets, additional policy support from Beijing and a stronger pickup in private investment). Still, the WEO thinks that on balance the risks to its forecasts remain tilted to the downside. And it lists a familiar set of downside risks: a further slowdown in China’s economic growth; more volatile commodity prices due to climate and geopolitical shocks; stubborn underlying inflation; a repricing in financial markets (last week’s bond market turmoil was an example of this kind of effect); rising debt distress; an intensification of geoeconomic fragmentation; and a resumption of social unrest. And as already noted, the Fund’s new numbers do not consider recent events in the Middle East.

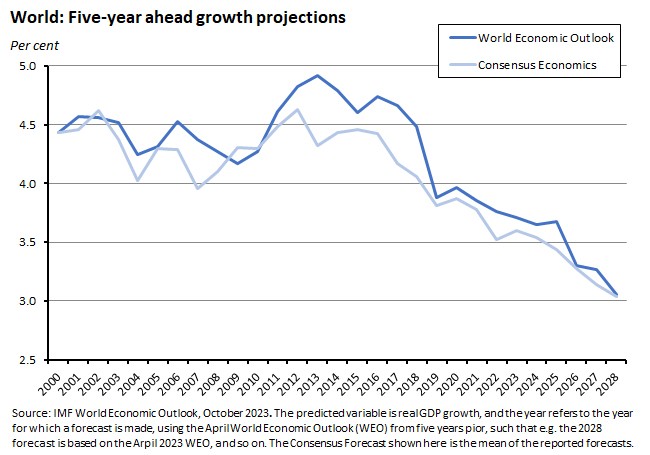

While the IMF’s (pre-Middle East turmoil) near-term outlook has improved somewhat, the WEO sounds downbeat about the future further out, pointing out that ‘forecasts for the growth rate of global GDP over the medium term are at their lowest in decades.’ The WEO compares five-year ahead WEO forecasts between 2000 and 2023 and finds that medium-term growth prospects have fallen by 1.9 percentage points since the April 2008 WEO forecast for 2013 growth. (For Australia, the drop is about 1.25 percentage points.) All of the world’s ten largest economies and 81 per cent of all economies have seen a decline in their medium-term growth prospects. And it is not just the IMF: repeating the exercise using Consensus Economics forecasts generates the same kind of results. About three-quarters of the decline in performance reflects weaker per capita GDP projections, so it is not slowing population growth that is doing most of the work here. Rather, it is lower productivity growth, a decline in labour force participation and a slowdown in capital deepening.

Australian consumers more upbeat in October

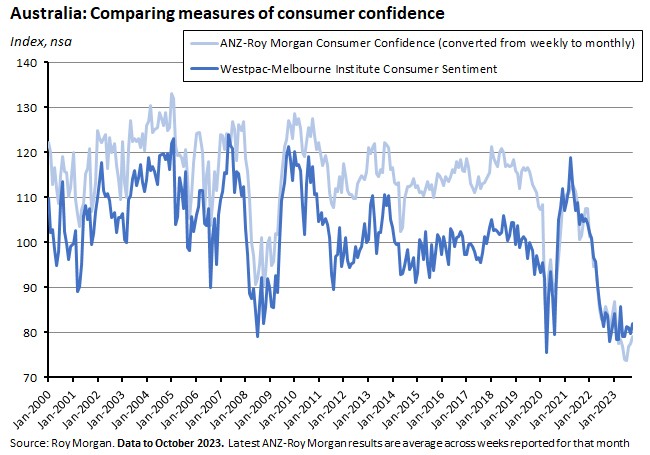

The Westpac-Melbourne Institute Index of Consumer Sentiment (pdf) rose 2.9 per cent to an index reading of 82 this month, up from 79.7 in September. Despite the rise, the index remains in deeply pessimistic territory. Westpac noted that the modest gain this month reflected only a ‘muted lift in sentiment’ in response to the RBA’s extended pause, with the headline index up just 3.7 per cent since the last increase in the cash rate target was delivered in June this year (sentiment in households with a mortgage is up 5.9 per cent over the same period). Survey results show ‘some faint glimmers of hope around family finances and the outlook for jobs’ as the ‘family finances vs a year ago’ subindex rose 2.7 per cent over October; the ‘finances next 12 months’ subindex was up 2.6 per cent, and the Westpac-Melbourne Institute Unemployment Expectations Index fell 2.7 per cent indicating that more consumers expect the unemployment rate to fall over the year ahead. Overall, however, high inflation and renewed concerns about future interest rate increases continue to hold down household sentiment.

The weekly measure of household confidence tells a broadly similar story. The ANZ-Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence Index rose 1.9 points to an index reading of 80.1 for the week ending 8 October 2023. This was the first index reading above 80 for eight months and the highest reading since the week ending 19 February 2023. ANZ said that confidence has been trending upwards in recent weeks due to improving sentiment around personal finances. This could reflect stronger wage and employment growth over the past year but might also reflect the fact that the ‘current finances’ question – which asks participants to compare the state of their current finances to a year ago – will now be capturing the impact of household sentiment in the final months of 2022, when inflation and interest rates were already a pressing issue.

The survey measure of weekly inflation expectations eased by 0.1 percentage point to 5.1 per cent.

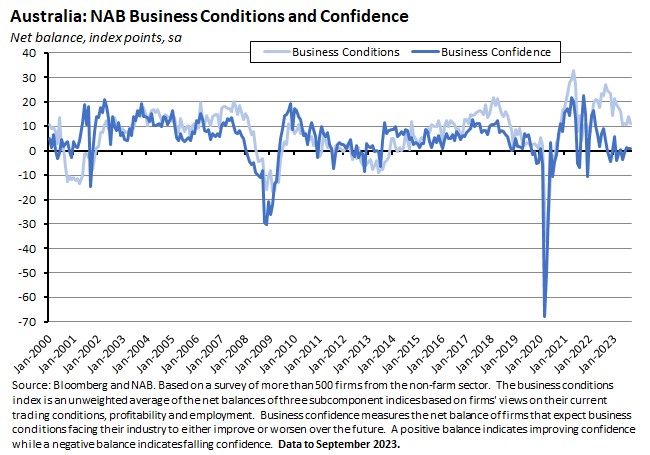

Business conditions resilient in September with eased cost pressures

According to the September 2023 NAB Monthly Business Survey, business conditions eased slightly last month but remain above their long-run average, as the index fell from +14 points in August to +11 points. Likewise, by subindex, trading conditions fell three points to +16 points, profitability dropped five points to +8 and employment fell one point to +8, while all three remained above their respective long-term averages. NAB said there were some significant monthly declines in conditions by industry, with sharp drops for Mining, Transport & utilities, Construction and Retail, although in trend terms conditions remained robust with only the Construction and Wholesale industries reported conditions below +10 index points.

Business confidence was unchanged in September with the index steady at +1 index points. Forward orders rose two points to +2 index points while capacity utilisation slipped to 84.2 per cent from 85.1 per cent.

Price and cost growth showed signs of easing last month. Labour cost growth slowed from 3.2 per cent in August to two per cent in September (quarterly equivalent terms) while purchase cost growth fell from 2.9 per cent to 1.8 per cent over the same period. At the same time, the rate of growth of final product prices dropped from 1.7 per cent to one per cent, although retail price growth was unchanged at 1.8 per cent.

What else happened on the Australian data front this week?

The ABS Monthly Business Turnover Indicator rose in eight of the 13 published industries in August 2023 (seasonally adjusted basis) with the largest rise in Manufacturing (up 6.4 per cent) and the largest decline in Other services (down 2.6 per cent). On an annual basis, ten of the 13 published industries reported increases in turnover, led by Construction (up 19.2 per cent) and other services (up 9.2 per cent). The biggest declines were for electricity, gas, water, and waste services (down 22.3 per cent) and Mining (down 16.5 per cent).

The ABS said that for the week ending 16 September 2023, the number of payroll jobs was unchanged over month from 19 August 2023 but up 2.4 per cent over the year since 17 September 2022.

Other things to note . . .

- Last Friday, the RBA published the October 2023 Financial Stability Review. According to the Review, ‘global financial stability risks are elevated due to challenging macroeconomic conditions,’ and it warns that stress in China’s financial system could spill over into the global financial system, including Australia, via slower growth and higher risk aversion. Nevertheless, the Review judges that ‘the Australian financial system remains strong.’ Some specific points worth noting:

- In terms of the resilience of households, the Review says that although higher inflation and interest rates are putting pressure on household budgets and have also prompted an uptick in arrears and personal insolvencies, the ‘vast majority’ of households have continued to service their debts, supported by a strong labour market, the ability (of some) to draw down savings accumulated during the pandemic and by squeezing discretionary spending. Given this context, the RBA reckons that ‘the risks to the broader financial system from housing lending remain low.’

- The RBA does think that a ‘small but rising share of borrowers are on the cusp, or in the early stages, of financial stress’ and estimates that the share of variable-rate owner-occupiers whose essential expenses and mortgage costs exceed their income had risen from one per cent in April 2022 to around five per cent by July this year. Of the five per cent with insufficient current income, the RBA estimates that around 70 per cent have sufficient savings to finance their cashflow shortfalls for at least six months at current interest rates. (Note that the RBA reckons if essential expenses are augmented to include what are technically discretionary but in practice potentially difficult-to-adjust items such as private health insurance and private school fees, the relevant increase to date is from three per cent to around 13 per cent instead of one to five.)

- A further 50bp increase in rates would boost the estimated share of variable-rate owner-occupier borrowers who are unable to cover their essential expenses from around five per cent to around seven per cent.

- In the case of a two-percentage point increase in the unemployment rate, the RBA estimates that only 1.25 per cent of variable-rate owner-occupiers would become at risk of depleting their financial buffers within one year.

- In terms of the resilience of businesses, the Review reports that a strong post-pandemic recovery supported profitability and robust demand has allowed most businesses to pass on higher input costs. Although more recently, pressures from higher input costs, higher interest rates and slowing demand have emerged.

- Company insolvency rates have risen back to around pre-pandemic levels, with rising insolvencies in the construction industry accounting for on-third of the recent increase, with residential builders locked into fixed-price contracts particularly vulnerable. But the Review also notes that banking sector exposures to insolvent businesses appear to be limited, consistent with low rates of non-performing loans.

- The Review also cites pressure on profitability and asset valuations in office and retail commercial real estate (CRE) due to higher vacancy rates and weak rental growth as well as higher interest rates but it sees limited signs of financial stress among owners of Australian CRE, concluding that ‘the risks to the broader financial system stemming from the CRE sector remain low.’

- Banks’ credit quality overall faces some risk from tighter financial conditions and weaker economic activity, but the RBA’s view is that the level of risk remains low, as does risk for non-bank lenders.

- Finally, the Review highlights a redistribution of risk in the Australian insurance landscape; a challenging reinsurance market is pushing retail insurers to absorb more risk, and higher premiums (reflecting higher inflation and a sequence of severe natural disasters boosting the cost of claims, increasing reinsurance expenses, and squeezing profitability) are putting pressure on affordability for businesses and households, which is likely to see them taking on more risk in the form of higher excess payments and reduced cover. According to the RBA, premium increases are most severe in areas heavily exposed to natural disasters which, in turn, could reduce bank willingness to lend to those regions.

- RBA Assistant Governor (Financial Markets) Chris Kent gave a speech on Channels of Transmission which examines the way that tighter monetary policy influences demand and inflation. Kent explains that the transmission mechanism moves through the economy in three steps:

- Changes in the cash rate produce changes in other interest rates in economy by changing bank funding costs which are then passed on to variable-rate borrowers and to depositors. Kent says that since May 2022, Australian banks have passed on about 75 per cent of the increase in the cash rate to depositors – a pass-through rate which is much higher than in the US (35 per cent) and New Zealand (50 per cent), perhaps reflecting Australian banks’ focus on variable-rate borrowing and lending.

- Changes in interest rates then influence economic activity. Kent lists fives channels through which this occurs:

- The cash-flow channel: higher interest rates boost debt service payments for debtors while lifting earnings on savings for creditors. Since May 2022, required household mortgage payments have risen from around seven per cent of household disposable income to nearly 10 per cent, for example. Overall, Kent says the RBA reckons the 400bp of tightening to date should have the net effect of reducing overall household spending by 0.4 – 0.8 per cent per year.

- The intertemporal substitution channel: higher interest rates change the incentive to save relative to spend and influence business decisions regarding investment. According to Kent, recent RBA estimates suggest that after two or three years the current cycle’s 400bp of tightening mean that business investment might be four per cent lower than it would otherwise have been.

- The asset price channel: higher interest rates lead to lower asset prices by reducing the discounted value of expected future cash flows. The RBA thinks each one per cent fall in wealth depresses consumption by 0.1 to 0.2 per cent (but note that house prices, for example, have been rising, not falling in recent months).

- The credit channel: higher rates tend to make lending riskier, leading to less borrowing and lower demand. Kent said that the 400bp increase in the cash rate has reduced the borrowing capacity of the typical Australian household by about 30 per cent via the impact on debt serviceability assessments (Australian banks assess a borrower’s ability to service debt by considering the impact of interest rates rising by a further three percentage points from current levels).

- The exchange rate channel: all else equal, higher Australian interest rates increase the demand for Australian assets and drive up the Australian dollar. The RBA’s estimate is that a 100bp cash rate increase would lead, all else equal, to a five to ten per cent appreciation in the trade-weighted exchange rate which would in turn reduce inflation by between 0.25 and 0.5 percentage points after two years (but note that all else is not equal, for example some major overseas central banks including the US Fed have increased their policy rates by more than the RBA).

- These induced changes in economic activity then feed through into changes in inflation.

- The Productivity Commission (PC) published the September 2023 edition of its Quarterly Productivity Bulletin. Focusing on the June quarter 2023 national accounts results, the PC highlights the combination of an increase in economy-wide hours worked alongside a decline in labour productivity. It explains these developments as the joint product of a household labour supply response to cost-of-living pressures and declines in real wealth, a tight labour market that saw more people enter (new entrants and more marginal workers might have lower skills, and there would be less capital per worker, both contributing to lower productivity in the short term), and the pandemic (the end of a COVID-19 ‘productivity bubble’ that had been driven by the temporary closure or shrinking of lower productivity sectors).

- Grattan’s Tony Wood on why Australia urgently needs a climate plan.

- As well as the flagship World Economic Outlook, the IMF has also published the full Global Financial Stability Report, and is releasing new Regional Economic Outlooks.

- Related, an FT Big Read on US attempts to reboot the IMF and World Bank.

- Claudia Goldin won the 2023 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel ‘for having advanced our understanding of women’s labour market outcomes.’ According to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, Goldin’s work ‘provided the first comprehensive account of women’s earning and labour market participation though the centuries. Her research reveals the causes of change, as well as the main sources of the remaining gender gap.’ Here are the Academy’s ‘popular science background’ (pdf) and ‘scientific background’ (pdf) on Goldin’s work. Her latest NBER paper is Why Women Won which considers ‘how, when and why did women in the US obtain legal rights equal to men’s regarding the workplace, marriage, family, Social Security, criminal justice, credit markets, and other part of the economy and society, decades after they gained the right to vote?’ Downloadable pdf here. The FT interviewed Goldin about her recent book Career and Family last year. And Tyler Cowen reposted his 2021 conversation with Claudia Goldin on the Economics of Inequality.

- Noah Smith on after the Pax Americana (already linked in the main text).

- The Economist magazine has a special report on what it calls ‘Homeland Economics’ – a ‘protectionist, high-subsidy, intervention-heavy ideology administered by an ambitious state.’

- The new IEA medium-term gas report says that after a decade of unprecedented expansion, growth in global demand for natural gas is expected to slow in coming years in line with declining consumption in mature markets, with future growth highly concentrated in fast-growing Asian markets. China is expected to account for almost half the growth in global demand between 2022 and 2026.

- A Chatham House report on the consequences of Russia’s war on Ukraine for climate action, food supply and energy security.

- Two VoxEU columns on how economics can learn from history: Mark Harrison reviews the experience of economic warfare from the two World Wars to claim that ‘economic warfare does not win battles, but it helps to decide who will win them when they are fought’ while Linda Yueh considers what we can learn from three generations of currency crises, arguing that the 1980s Latin American debt crisis, the 1990s Mexico crisis, and the late 1990s Asian crisis all emphasise the importance of credible policymaking and of the sustainability of trade and budget deficits.

- The Basel Committee report on the 2023 banking turmoil – which it says was ‘the most significant system-wide banking stress since the Great Financial Crisis in terms of its scale and scope.’ The report’s findings highlight ‘fundamental shortcomings in basic risk management of traditional banking risks (such as interest rate risk and liquidity risk; and various forms of concentration risk)’ as well as a failure to appreciate the overall relationship between various individual risks, a poor risk culture, a failure to respond adequately to supervisory feedback and recommendations and ‘inadequate and unsustainable business models, including an excessive focus on growth and short-term profitability (fuelled by remuneration policies), at the expense of appropriate risk management.’

- This episode of the Odd Lots podcast covers last week’s bond market turmoil.

- Barry Ritholtz in conversation with Michael Lewis about his new book on SBF and FTX. I’m normally a bit of a Lewis fan. Not sure if I’ll be grabbing this one though.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content