Overview

- Household consumption ended 2025 on a surprisingly strong note. This was a key contributor to unexpected strength in private demand that prompted the RBA to tighten monetary policy last week.

- This week’s monthly spending and consumer sentiment readings suggest not all that strength will be sustained into the start of this year.

- Consumer sentiment fell in February 2026 in response to the RBA’s rate hike and expectations of more tightening to come, although the decline was milder than the hit to confidence usually delivered by rate increases.

- Key uncertainties include the sustainability of that December quarter 2025 strength in consumption and how much the RBA’s tap on monetary policy brakes will influence actual spending behaviour over coming months.

In this week’s note, we consider updates on the state of household spending in the final month of 2025 and consumer sentiment in February 2026, with surprising strength seen in private demand in the fourth quarter of last year. We also analyse post-pandemic patterns in household consumption and consider some of the implications for monetary policy.

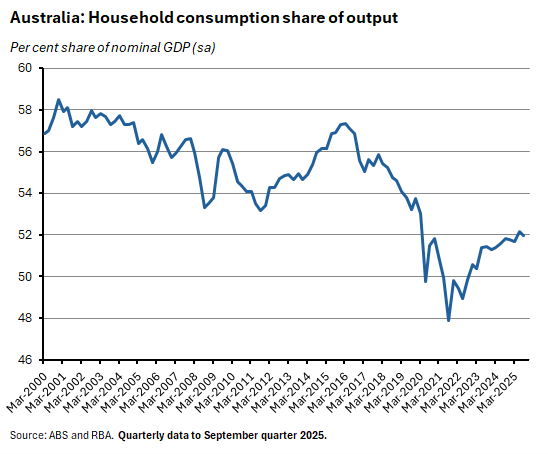

Household consumption is the largest expenditure component of GDP, and although its share has fallen in recent years, it continues to account for more than half of all Australian output. No surprise, then, that developments in consumption are key drivers of economic outcomes and that expectations about future changes in consumption growth are critical to the economic outlook, informing the RBA’s views on demand-supply balances and prospects for inflation.

At times, Australia’s central bank has struggled to come to grips with consumption growth post-pandemic, as household spending patterns shifted in dramatic ways in response to the closing and re-opening of the Australian economy. For a time, the RBA was too optimistic, anticipating recovery in consumption that took longer than expected to manifest. More recently, Martin Place was caught out by the strength of consumer spending in the final quarter of last year, with this stronger-than-expected increase contributing to the unanimous decision to deliver that 25bp rate hike at the February meeting of the Monetary Policy Board (MPB).

In that context, this week has brought us two useful updates on the consumption story.

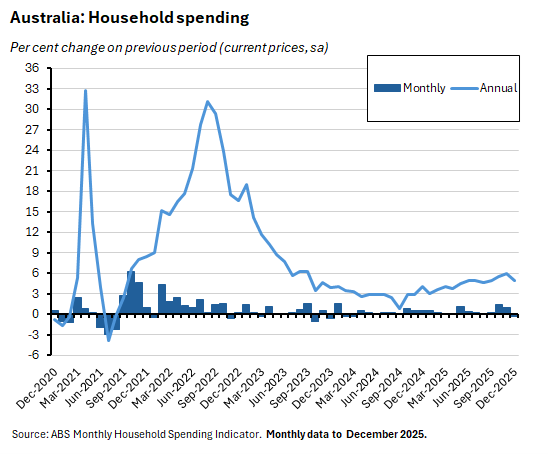

First, the ABS Monthly Household Spending Indicator (MHSI) reported that householdspending was down 0.4 per cent month-on-month (current prices, seasonally adjusted) in December 2025, although it was still up five per cent over the year.

That was important because December’s monthly decline followed strong monthly increases of 1.4 per cent in October and one per cent in November last year, which together contributed to stronger-than-expected surge in private demand. Consumption spending was boosted by major sales and cultural events, and the ABS notes that the December monthly decline is consistent with households bringing forward some purchases to take advantage of earlier sales events.

This intertemporal reallocation of spending was visible in changes in spending on discretionary items, with the Bureau highlighting notable falls in expenditure on clothing and footwear and on furnishings and household equipment.

Another factor highlighted by the ABS as contributing to the softer December result was a decline in health spending in December, following several months of growth. Some of this fall was due to higher bulk-billing rates reducing out-of-pocketcosts for households.

On a quarterly basis, the ABS said the volume of spending rose 0.9 per cent over the December quarter 2025, marking a sixth consecutive quarterly rise. Spending volumes were also up 2.4 per cent over the year, representing the strongest result recorded in 2025, consistent with a strong end to the year for private demand.

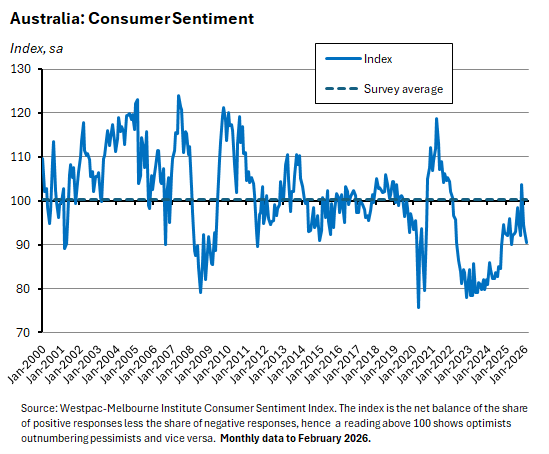

The second datapoint came in the form of the Westpac-Melbourne Institute Consumer Sentiment Index. Economic theory suggests that changes in household expectations regarding future economic conditions should influence current spending decisions. Hence shifts in consumer sentiment should tell us something about future spending intentions, even if the relationship is not straightforward.

According to the index, sentiment fell 2.6 per cent in February 2026, dropping to a reading of 90.5 from 92.9 in January. Indeed, all five subindexes were below 100 this month, with Westpac noting that this was only the second time since October 2024 that pessimists have outnumbered optimists across every survey component.

Unsurprisingly, a key driver of the fall in sentiment was the MPB’s vote for a 25bp rate increase, along with expectations that more policy tightening was likely to follow. According to Westpac, nearly two-thirds of consumers who expressed a view (some 64 per cent) now anticipate higher mortgage rates over the next year. That expectation is now at its highest level since July 2024, when inflation was still running at four per cent.

Interestingly, Westpac also noted that the hit to sentiment was nevertheless relatively mild when compared to experience. This month’s 2.6 per cent fall was markedly smaller than the average 3.8 per cent decline in sentiment that historically follows an increase in the cash rate. That difference could point to the fact that this month’s rate increase was widely expected and as such was partly embedded in household expectations before the actual decision.

Putting both results together, they suggest that household consumer spending could soften as we move through the first quarter of this year, which would in turn ease some RBA concern about surprisingly strong spending in the final quarter of 2025.

Household income and consumption after COVID-19

A complicating factor here is that post-pandemic swings in the consumption story have simultaneously made understanding household spending patterns more important and more challenging.

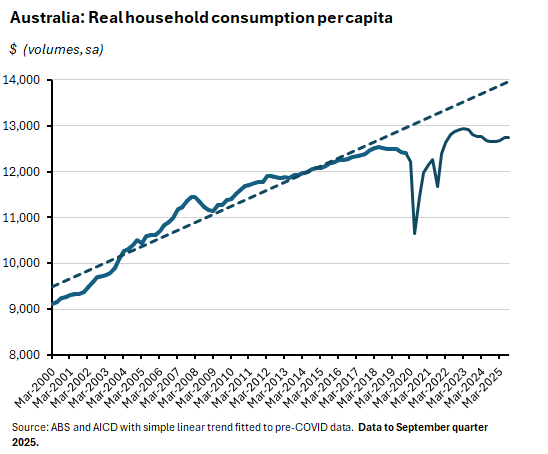

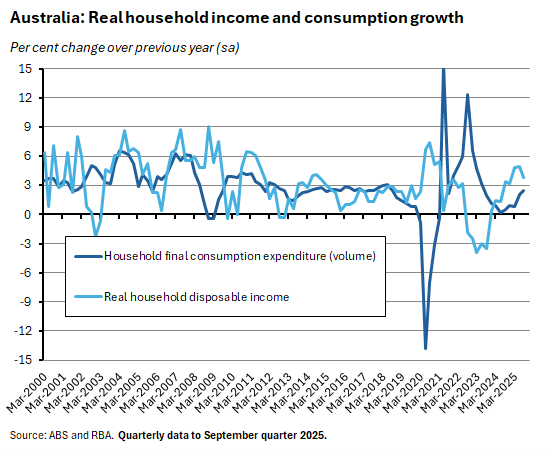

For example, Box B in the February 2025 Statement on Monetary Policy (SMP), discusses developments in household consumption and income since the pandemic. One important development highlighted here is the weakness of real household disposable income per capita, relative to its pre-pandemic trends through to the start of last year, with the SMP noting that ‘this has been among the weakest periods of real income growth since the 1960s and has occurred alongside a period of historically weak productivity outcomes’.

Why was income growth so weak? Part of the story is that real wage growth as measured by the WPI has been poor for much of the post-pandemic period. Yet real labour income overall still grew strongly, thanks to the impact of promotions, bonuses, job-switching (to higher paid roles), and a rise in the employment-to-population ratio. But this in turn was more than offset by the combined drag on net disposable income arising from lower gross mixed income (mainly in the form of reduced small business income), higher interest rates and higher tax payments. This negative effect was also large enough to offset a significant post-pandemic rise in aggregate household wealth.

The squeeze on per capita income growth was even more intense and that income squeeze was an important headwind for household consumption. Real household consumption was largely stagnant between 2022 and 2024. Strip out population growth and per capita consumption fell from late 2022 through 2024.

That weakness dragged down overall economic growth, with overall real GDP growth slumping to an annual rate of just 0.8 per cent by the September quarter 2024, its lowest rate in more than three decades (excluding the COVID 19 recession). Absent public demand, the economy would likely have fallen intooutright recession, as opposed to the per capita recession it did suffer.

As noted above, for much of this period, the timing of an expected recovery in household consumption growth represented a key uncertainty for the Australian economic outlook as actual consumption spending repeatedly undershot the RBA’s forecasts, with growth in household spending lagging the upturn in household disposable incomes.

Household consumption and inflation

That pattern shifted again in 2025 as consumption growth started to gain momentum into the second half of the year.

Recall that in last week’s analysis of the RBA’s rate hike, we listed a series of factors set out in the new February 2026 SMP that explained the shift in the central bank’s thinking and the consequent move to tighten monetary policy. Prominent was the way in which the rise in private sector demand through H2:2025 exceeded RBA expectations, with the SMP emphasising that ‘growth in private demand looks to have been especially strong in the second half of 2025.’ That strength reflected several factors, including a rebound in dwelling investment and a jump in business investment due to spending on data centres. But it also included a prominentrole for household consumption. Hence, according to the SMP:

‘Household consumption grew solidly in the September quarter and timely indicators of household spending suggest that consumption growth continued to pick up during the December quarter and by much more than expected in the November [SMP].’

The SMP attributes some of this strength to temporary factors, with households bringing forward spending to take advantage of sales and promotions – a take that is consistent with December spending numbers discussed above. But the SMP also notes higher-than-expected increases in household income growth that it says could have contributed to strength in underlying consumption. That lift to real income growth came from the previous slowdown in inflation, from the impact of the rollout of the Stage Three tax cuts, and from lower interest rates. Low unemployment and a relatively tight labour market (and therefore a reduced risk of joblessness) could also have played a supportive role. There may also have been positive wealth effects from higher home prices for homeowners.

Again, some effects will fade over time. Prices and now interest rates have increased, for example, as reflected in this month’s decline in sentiment. The boost to spending from December quarter sales and events will also drop outof March quarter numbers.

This means a key question for the growth and inflation outlook remains. Just how much of December quarter strength in household consumption proves to be persistent, as opposed to transitory?

Households and the monetary policy transmission mechanism

A second and closely related question is how households will react to last week’s decision to apply the monetary policy brakes and how quickly this will influence actual spending decisions, as opposed to the swing in sentiment that has already appeared.

Higher interest rates will influence household spending by directly increasing interest payments and interest income and hence the amount of cash that households have available to fund spending. This is known as the ‘household cash flow channel of monetary policy.’* And as noted above, there could also be an impact via expectations of a greater probability of future rate increases.

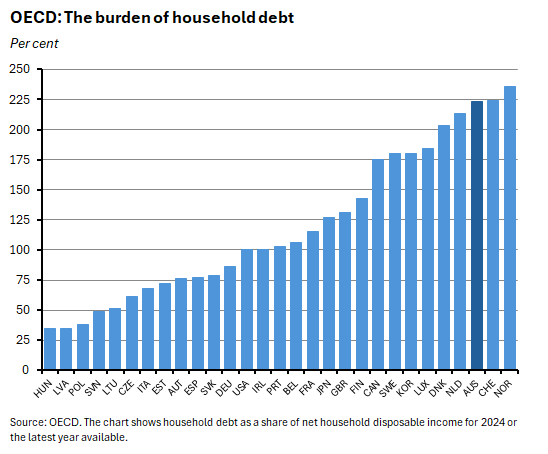

The size of the direct impact will be influenced by the extent to which changes in the cash rate are passed on to the lending and savings rates faced by households, the relative size of household holdings of interest-bearing assets and liabilities, and the sensitivity of household spending to changes in cash flows. With the debt burden of Australian households among the highest in the OECD and with variable rate mortgages once again prevalent, one might expect this channel to operate quite strongly in Australia. And work by the RBA has found that the monetary policy pass-through to outstanding mortgage rates is quicker in Australia than in most other advanced economies, although it has not found evidence that the overall potency of monetary differs significantly from our peers.

Prior to the pandemic, the RBA reckoned a reduction in the cash rate by 100bp was associated with an increase in household income of around 0.9 per cent, which would then increase household spending by about 0.1 to 0.2 percent through the cash flow channel.

Strikingly, however, there was a large shift in the sensitivity of household cash flows to changes in the cash rate between 2020 and 2022, due to the dramatic increase in the share of fixed-rate mortgages (between March 2020 and January 2023, the share of fixed-rate housing credit rose to almost 40 per cent of housing credit outstanding). As a result, for a time, short-term changes in the policy rate seem to have had a negligible effect on household disposable income at the aggregate level, leaving monetary policy to seek traction through other channels.

More recent work, however, has found that as the fixed-rate share of mortgages has fallen back to historical lows, the sensitivity of overall household income to changes in interest rates has returned to around its pre-pandemic average. And the same is true for the size of the consumption response to changes in the cash rate via the cash flow channel.

*Note that there are other channels through which changes in interest rates will influence household spending. Higher rates could lead to lower asset prices, which would then reduce household wealth (the wealth channel). Higher rates could also encourage households to save more, thereby lowering current consumption (the intertemporal substitution channel). Note that MARTIN, the RBA’s macro model, assumes the impact of the cash flow channel is relatively small, although it is also quicker to influence economic conditions than the savings and investment and asset price channels.

Other Australian data points to note

According to the NAB Monthly Business Survey, NAB’s index of business conditions fell three points to +7 index points in January 2026, suggesting a softening of activity at the start of this year, driven by declines in trading conditions and profitability. That said, on a trend basis, conditions remain a little above average. In contrast, the survey’s index of business confidence rose by one index point last month to reach +3 index points, just below the series’ long run average. The January survey also reported a further decline in capacity utilisation, which eased slightly to 82.9 per cent. The utilisation rate is now down 0.6 percentage points from its peak but remains above average rates in six out of eight industries. Finally, on the cost front, labour cost growth fell 0.5 percentage points to 1.3 per cent (quarterly equivalent rate) while growth in purchase costs slowed by 0.2 percentage points to 1.1 per cent. Final product price growth fell 0.3 percentage points to 0.5 per cent. According to NAB, all cost and price growth measures now sit at their lowest levels since 2021, in positive news for the inflation outlook.

The ABS said the total number of new loan commitments for dwellings rose 5.1 per cent (seasonally adjusted) over the December quarter 2025 to be 13.4 per cent higher over the year. Commitments to owner occupiers were up 4.8 per cent quarter-on-quarter and up 7.4 per cent year-on-year, with commitments to first home buyers rising by 6.8 per cent in quarterly terms, outpacing a 3.6 per cent quarterly rise for non-first home buyers. The number of loan commitments to investors grew 5.5 per cent over the December quarter to be 23.6 per cent higher than in the December quarter 2024. The Bureau noted this was the largest rise in the number of first home buyer loans since the December quarter of 2023. That growth likely reflects the impact of the expansion of the federal government’s Five per cent Deposit Scheme and the introduction of the government’s Help to Buy scheme. The size of the average first home buyer loan rose by a record 8.5 per cent to $607,624 last quarter. The ABS also said new investment loans reached record numbers and values in the December quarter of 2025.

According to the ABS there were 1,036,660 short-term visitor arrivals in December 2025, up 9.7 per cent on the same month the year before. Total arrivals were 1,996,200, an annual increase of 7.7 per cent, while total departures were 2,451,810 (up 8.4 per cent over the year). The 138,610 arrivals from the UK (behind only New Zealand’s 142,420 trips) were the largest on record for that country.

Further reading and listening

- Treasury Secretary Jenny Wilkinson’s opening statement to the Economics Legislation Committee notes that Treasury still expects ‘solid annual growth’ in the economy over the next two years. Wilkinson also said Treasury is monitoring the impact of recent natural disasters and currently estimates that the combined impact of bushfires in Victoria and flooding in Queensland could result in nearly $1 billion of lost economic activity, or around 0.1 per cent of real quarterly GDP.

- The AFR reports that the Australian Office of Financial Management, or Australia’s debt office, is in chaos.

- From last Friday, RBA Governor Bullock’s opening statement to the House Standing Committee on Economics. And the Hansard record of the meeting. And from this week, video of a fireside chat with Deputy Governor Andrew Hauser (the discussion only starts a bit more than 20 minutes in).

- Relevant for the previous discussion, the e61 Institute’s Gianni La Cava analyses the cash flow channel of monetary policy in Australia and says it is weaker than many assume. That is because although changes in the cash rate do feed directly into changes in mortgage rates, the subsequent response of actual mortgage repayments to those changes in rates is much more muted. Some of that is down to inertia – households do not change actual repayments in line with required repayments – and some of it reflects the presence of large liquidity and prepayment buffers which allow households to smooth consumption over time.

- The Grattan Institute’s suggestions (in a submission) on how to bring down Australian electricity prices.

- Productivity Chair Danielle Wood’s speech explains how the PC seeks to influence policy.

- In the AFR, Stephen Grenville offers a cautiously positive take on the prospect of Kevin Warsh as Fed Chair.

- A couple of interesting papers from Global Trade Alert. One looks at how companies are seeking to build ‘geopolitical muscle’ and the other reviews updated measures of state economic intervention.

- Mapping the transition channels from China shocks to the global economy.

- How will ‘involution’ in China end?

- On pricing cascades and inflation in a networked economy.

- From the NY Fed, an anatomy (not autopsy) of the Phillips curve.

- The WSJ compares the AI investment boom currently underway in the United States with previous capital splurges. It estimates that at a projected 2.1 per cent of GDP this year, it would be bigger than the Apollo space program (0.2 per cent), the build-out of the US interstate highway system (0.4 per cent), and the 1850s railroad boom (2.1 per cent). But not yet up there with the Louisiana purchase (three per cent).

- Related, Greg Ip with a thought-provoking piece on the changing position of capital and labour.

- Also from the WSJ, a profile of Amanda Askell, resident philosopher at Anthropic.

- This OECD working paper seeks to track trends in AI incidents and hazards, as reported by the media.

- Snobby about Excel: Dan Davies on AI and the end user effect.

- The latest edition of the Journal of Economic Perspectives includes symposia on fertility rates and on labour market competition.

- The Economist magazine reckons hedging your portfolio looks tricky.

- Also from the Economist, the Schumpeter column on how Jeffrey Epstein’s ghost is haunting the grand old men of capitalism.

- The FT magazine on the ideas of Michael Sandel.

- Daniel Waldenstrom makes the positive case for inherited wealth.

- Nouriel Roubini warns of the coming crypto apocalypse.

- What can we learn from the nineteenth century urbanisation experience?

- The IMF talks to Johan Norberg about what makes and breaks Golden Eras.

- The Odd Lots podcast on the crypto winter and other asset price shifts.

- The ChinaTalk podcast has a long conversation with grand strategist Edward Luttwak on military revolutions that also weaves in his life story and some of his favourite reading.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content