Last Friday, the RBA published the November 2022 version of its Statement on Monetary Policy (SOMP). As well as setting out the central bank’s latest forecasts for growth (down), inflation (up) and unemployment (up), the SOMP also explored the risks to the outlook, explaining that since August, downside risks to growth and upside risks to inflation had both increased.

That message was echoed in this week’s data on consumer sentiment and inflation expectations. On the one hand, consumer confidence has continued to fall, dropping to levels last seen at the start of the pandemic. That’s signalling important risks to future consumer spending and economic activity. On the other hand, current measures of inflation expectations have risen in line with actual inflation. That threatens unhelpful changes in inflation psychology and therefore in the future wage- and price-setting behaviour of workers and firms (although it’s worth noting that financial market measures still indicate that the RBA’s inflation target looks credible in the medium term).

No wonder, then, that the RBA warned in Friday’s SOMP that, depending on how the economy develops from here, Martin Place could potentially choose either to increase the future size of hikes in the target cash rate or to put future rate moves on a temporary hold. Clouded in uncertainty, the RBA’s narrow path looks an increasingly precarious one.

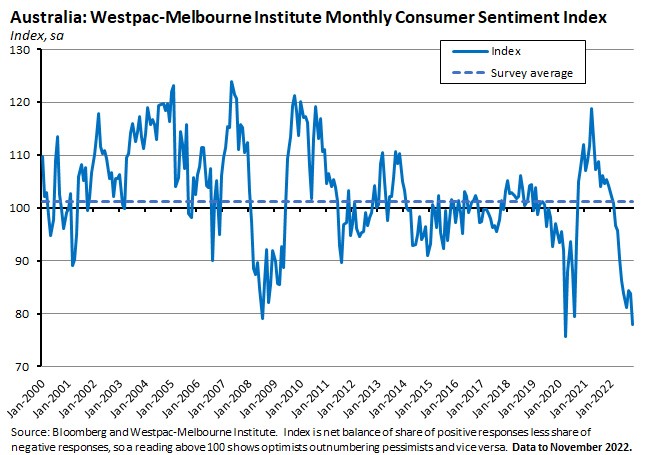

Consumer confidence continues to crumble . . .

The Westpac-Melbourne Institute Index of Consumer Sentiment slumped 6.9 per cent to a reading of 78 in November. At that level, the index is below the low of 79 reached during the GFC and only slightly above the 75.6 reading associated with the start of the pandemic in April 2020.

Westpac pointed to the combined impact on sentiment of the surge in headline CPI inflation to 7.3 per cent in the September quarter of this year, the forecasts in the October Budget for sharply higher electricity and gas prices over the year ahead, and the RBA’s latest 25bp rate hike in November as factors behind the fall. The RBA meeting took part mid-way through the survey week and Westpac noted that sentiment among those surveyed before the cash rate decision registered an index level of 83.1 vs an index level of 75.6 among those surveyed afterwards. The survey results also suggest that October’s Budget was not particularly well-received by households, with a relatively high 35 per cent saying it had worsened their financial outlook. That’s well above the 14-year average of 30 per cent, although it is also well below the 58 per cent recorded in 2014, the last time a new government introduced its first budget.

Digging into the subcomponents of the sentiment reading, this month’s survey showed an 11.2 per cent collapse in the ‘family finances, next 12 months’ subindex, along with seven per cent declines for the ‘economic outlook, next 12 months’ and ‘economic outlook, next five years’ subindices. According to Westpac, both of the ‘economic outlook’ readings deteriorated sharply following the RBA decision, dropping nearly 10 per cent between the pre- and post-RBA meeting samples.

The Westpac-Melbourne Institute Unemployment Index rose by more than five per cent this month, indicating that more consumers now expect to see an increase in unemployment over the coming year. And the Westpac-Melbourne Institute House Price Expectations Index dropped eight per cent, with falls particularly pronounced in the post-RBA meeting sample.

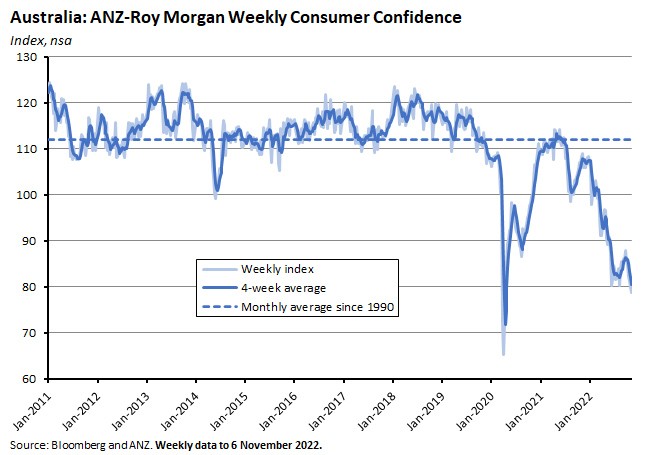

Consistent with the slump in monthly sentiment, a weekly index of consumer confidence also tumbled last week. The ANZ-Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence Index fell 1.5 per cent to 78.7. It has now fallen for six consecutive releases, delivering a cumulative decline of more than ten per cent. And, like the Westpac-Melbourne Institute measure, the ANZ-Roy Morgan index has now dropped to levels last seen in early April 2020 during the onset of the pandemic.

Also consistent with the Westpac report is the Roy Morgan-ANZ finding on respondents’ views of economic conditions: the ‘current economic conditions’ subindex fell 1.6 per cent in a third consecutive weekly decline, while the ‘future economic conditions’ subindex dropped 4.8 per cent. The latter has now fallen seven times over the past nine weeks and it too is at its lowest since April 2020.

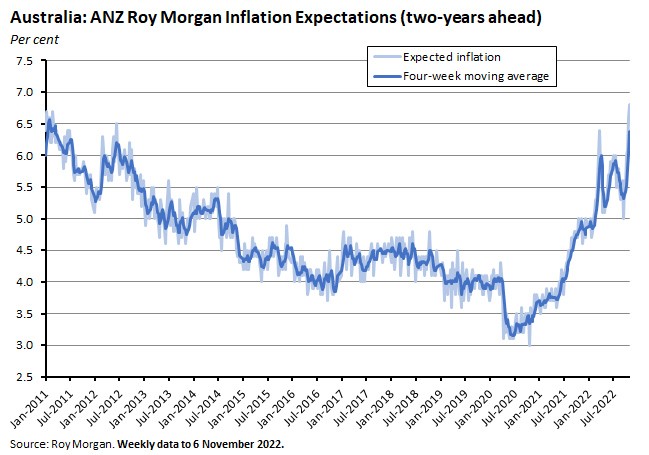

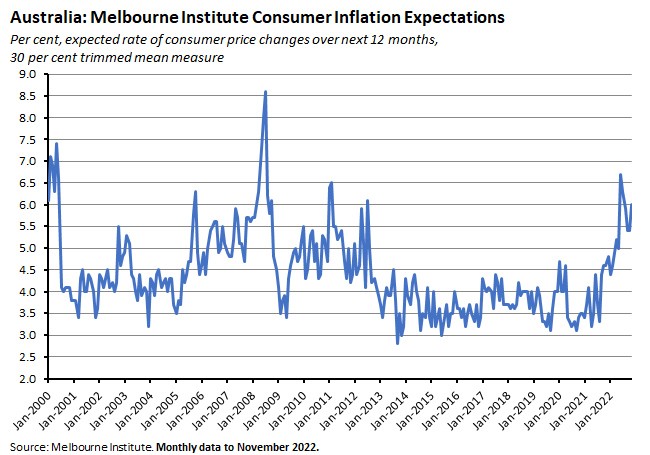

. . . while inflation expectations continue to climb

As emphasised in the RBA’s latest SOMP (see next story), Martin Place continues to see some significant risks around the future trajectory of inflation expectations. This week’s numbers indicated that the rise in the cost of living has pushed up consumers’ short-term inflation expectations. Hence the decline in consumer confidence is occurring in parallel with (as well as partly being driven by) rising inflation expectations. For example, the ANZ-Roy Morgan weekly inflation expectations index rose to 6.8 per cent last week. That’s the highest rate in the history of the series (which goes back to 2010).

Similarly, the Melbourne Institute’s November 2022 Survey of Consumer Inflationary and Wage Expectations reported that the expected trimmed mean inflation rate rose by 0.6 percentage points in November to six per cent. The Institute also said that uncertainty about inflation appears to have risen, with an increase in the share of consumers reporting ‘don’t know’ for year-ahead inflation.

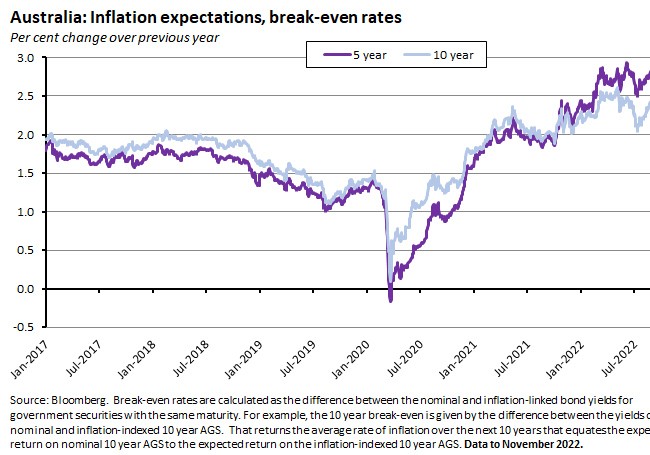

Still, there is also some good news to be had here, as measures of longer-term inflation expectations remain consistent with inflation returning to target over time. For example, although financial market measures of expected inflation outcomes over the five- and 10-year horizons have risen over recent months, they still indicate that markets expect inflation over this period to be back within the RBA’s target band.

The RBA is increasingly worried about downside risks to growth and upside risks to inflation.

Last Friday, the RBA published the November 2022 Statement on Monetary Policy (SOMP). As flagged in last week’s note, the SOMP included updated forecasts from the central bank showing that inflation and unemployment were both now expected to be higher than previously forecast and growth lower. The RBA also continues to predict a gradual disinflation process that now would only see headline and underlying inflation heading into the target band after 2024 but that would still avoid a recession (although growth would slow to a very subdued 1.5 per cent rate) and generate only a modest rise in the unemployment rate, to 4.25 per cent by the end of 2024.

One key takeaway from November’s SOMP was the increased uncertainty around the ‘narrow path’ that Martin Place is seeking to follow between inflation and recession. The commentary suggested that the risks to both of those outcomes have risen since the August 2022 SOMP.

In terms of the downside threats to growth, the November SOMP flags:

- A marked deterioration in the global environment. Synchronised policy tightening will slow global growth and lift the risks of a financial accident; activity in Europe is hostage to higher energy prices, a colder than expected winter, and an escalation in the war in Ukraine; and China’s outlook is being undermined by Beijing’s zero-COVID policy and a weak property sector.

- Increased pressure on Australian household budgets from rising prices and higher interest rates at the same time as balance sheets are suffering from falling house and other asset prices, and where the ‘magnitude of the decline of housing prices arising from higher interest rates is uncertain, especially given the high level of prices relative to incomes.’

Then there are the risks that inflation will surprise to the upside:

- In the near term, the impact of higher energy prices on domestic electricity and gas prices is now expected to be much greater than envisaged earlier in the year, and further increases in prices are now expected in 2023. In addition, domestic inflation has also been boosted by flooding and other bad weather which has led to higher food prices. And there are signs of broadening domestic price pressures in the form of a pick-up in services inflation and increasing rental price inflation.

- Persistently higher inflation rates now could produce changes in expectations about future inflation, leading to changes in price- and wage-setting behaviour, such that workers demand higher wages and firms pass on higher costs as higher prices (indeed, the SOMP flags that firm pricing behaviour had already started to change in late 2021/early 2022).

When it looks at these two sets of risks, the RBA’s best guess as to the implications for monetary policy is still that ‘interest rates will need to increase further’. But, the SOMP says, the uncertainty is such that any further rate rises are ‘not on a pre-set path’ and depending on circumstances the Board could yet decide either to revert to increasing the cash rate in larger steps or choose to hold it steady for a period.

Treasury endorses government intervention in the energy market

Treasury Secretary Steven Kennedy’s opening statement to the Economics Legislation Committee covered a lot ground, ranging across the global and domestic economic outlook, inflation, the fiscal position and Treasury staffing matters. But it was Kennedy’s comments putting Treasury’s weight behind policy ‘interventions that directly address…higher domestic thermal coal and gas prices…’ that grabbed the headlines.

The Treasury Secretary’s remarks began with the economic orthodoxy, citing the economists’ adage that ‘the solution to high prices is high prices’ since high prices simultaneously send a signal to suppliers and investors that an expansion in capacity is worthwhile and to consumers to look for alternatives and scale back demand. In this view, government intervention would serve only to impede necessary adjustments. According to Dr Kennedy, ‘in most circumstances Treasury would support such an approach.’ His statement then continued:

‘However, the circumstances of war-driven price shocks are different and outside the frame of such an approach. In our view, such shocks bring into scope government intervention.’

Kennedy said these ‘war-driven price shocks’ were leading to price and profits ‘well beyond the usual bounds of investment and profit cycles’ for producers while reducing household real incomes and undermining the profits, and in some cases the viability, of many businesses.

While the statement did not go on to spell out in any detail what a policy intervention should look like, it did provide several guidelines. Any policy intervention:

- Should not contribute further to inflation but instead directly address higher prices.

- Should reflect Australia’s position as a net exporter of energy as well as the differing positions across states and territories.

- Should be designed so as to not subtract from measures to reduce the emissions intensity of electricity production.

- Should be temporary and regularly reviewed.

Other points of note from the Treasury Secretary’s comments included:

- ‘It is becoming probable that major developed economies will soon experience recessions and it is likely China will grow at the lowest rate in over 30 years outside of the pandemic.’

- Australia has ‘been fortunate to be less affected than others by these global shocks, but nevertheless, we have been significantly affected.’

- Treasury’s preliminary estimate is for the recent floods in Eastern Australia ‘to detract around one quarter of a percentage point from GDP growth in the December quarter, largely offset by increased activity across the second half of the 2022–23 financial year.’

- The interaction of the price indexation of benefit payments with inflation may ‘have the unusual side-effect of reducing income inequality as payments grow as a share of average wages.’ The Age Pension is forecast to increase to 30.2 per cent of the Male Total Average Weekly Earnings (MTAWE) for singles and 45.5 per cent for couples by 2024, compared to averages over the past 20 years of 27.4 per cent and 42.9 per cent, respectively. Similarly, JobSeeker payments are forecast to rise as a share of MTAWE to 21.5 per cent for singles, a level not seen since 2006.

What else happened on the Australian data front this week (and last)?

According to the NAB Monthly Business Survey October 2022, business confidence fell four points to a neutral reading of zero last month, indicating that the number of optimistic firms in the survey is now equalled by the number of pessimistic ones. Forward orders also softened somewhat in October, falling from +14 to a still-healthy looking + seven index points. Capacity utilisation was unchanged at a rate of 85.8 per cent.

Despite a small one-point fall, business conditions remained strong at +22 index points. Profitability rose one point to +22 index points, and although trading conditions eased by six points that was to a still-high +31 index points. Employment fell two points to +14 index points.

Measures of costs pressures in the NAB survey were mixed. Growth in purchase costs rose to 4.1 per cent in quarterly terms, up from 3.7 per cent in September, but growth in labour costs moderated further, slipping from 3.1 per cent in September to 2.7 per cent in October. NAB noted that the rate of increase in labour costs has eased significantly relative to the sharp rise reported in July (4.6 per cent at a quarterly rate), suggesting that month’s result was something of an outlier, reflecting increases in award and minimum wages. Even so, NAB’s commentary also noted that labour costs remain elevated, reflecting underlying wage growth.

The ABS Monthly Household Spending Indicator showed household spending rose 28 per cent over the year to September 2022 on a current price, calendar adjusted basis. In annual terms, spending was up 43 per cent for services and 15 per cent for goods, and up 29.7 per cent for discretionary items and 26.4 per cent for non-discretionary ones. September’s result brought the 19th consecutive annual increase in spending and saw expenditure up 19.8 per cent relative to pre-pandemic (September 2019) spending levels. The ABS said that there were particularly strong increases for items that had been most affected by last year’s lockdowns including clothing and footwear, hotels, cafes and restaurants, and transport.

The ABS Monthly Business Turnover Indicator for September 2022 fell in monthly terms in seven of the 13 industries for which the ABS publishes data. The ABS said the biggest monthly fall was in electricity, gas, water and waste services (down 18.9 per cent, partly reflecting moderation in wholesale electricity prices) while the biggest rise was in arts and recreation (up 9.4 per cent and boosted by attendance at a range of events, including the AFL and NRL finals series and the Women’s Basketball World Cup). All 13 published industries recorded year-on-year gains.

The number of weekly payroll jobs rose 0.4 per cent between the weeks ending 1 and 15 October 2022 as people returned to work after the school holidays, after having fallen 0.7 per cent over the previous fortnight. Job numbers were down 0.3 per cent over the month, but up 4.1 per cent over the year. The ABS also said that total wages fell 2.5 per cent over the fortnight and dropped 5.5 per cent over the month, while still being six per cent higher in annual terms. The Bureau noted that wages in October are subject to seasonal patterns due to the payment of periodic bonuses in many industries in September.

Australian life expectancy increased over the pandemic. According to the ABS, for the 2019-2021 period, life expectancy at birth was 81.3 years for males and 85.4 years for females. That was up 0.1 years for males and females when compared to the 2018-20 period, making Australia one of the few countries across the world to report increases in life expectancy in the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Bureau also said that Australia now has the third highest life expectancy in the world.

New ABS data releases on Education and work, Public sector employment and earnings (there were 2,160,000 public sector employees at end June 2022, of which 254,000 were employed by the Commonwealth government), and Marriages and divorces (the Bureau reported that marriage registrations were well below pre-pandemic levels for a second consecutive year).

The ABS published Jobs in Australia, with data covering the period 2015-16 to 2019-20.

Last Friday, the ABS said that the volume of retail trade rose 0.2 per cent in the September quarter 2022 to be ten per cent higher than in the corresponding quarter in 2021. This was the fourth consecutive quarterly increase in retail volumes but also the smallest since the end of COVID lockdowns in October 2021.

Listen to the latest episode on The Dismal Science podcast.

Other things to note . . .

- RBA Deputy Governor Michele Bullock gave a speech on The Economic Outlook that discussed the forecasts contained in the November SOMP.

- Also from the RBA, a new research paper that examines how local income inequality influences household debt and its composition. The paper finds evidence that households do tend to borrow more as local income inequality increases, suggesting a ‘keeping up with the Joneses’ effect.

- The Economic Society of Australia’s regular survey of economists finds a strong majority in favour of government intervention to limit increases in gas and electricity prices. Extra taxes on resource rents and domestic gas reservation policies were the favourite options, followed by subsidies for low-income consumers and domestic price caps.

- The Lowy Institute’s Richard McGregor reckons that in response to Chinese trade coercion, Australia should seek to entrench itself as an indispensable supplier of key commodities to China, in order to maximise its leverage with Beijing.

- From Bloomberg Businessweek, Why Australia is gearing up for possible war with China. The cited parallel with the WW1-era Triple Entente is…disquieting.

- The ATO’s corporate tax transparency report for 2020-21.

- New report from ACSI on the ASX200 and commitments to emissions reduction.

- Related, according to a report on global companies and net zero from Accenture, while 34 per cent of the world’s largest companies have now adopted a public net zero emissions goal, nearly all of them will fail to achieve this target without at least doubling their pace of emissions reductions by 2030.

- The messy unwinding of the New World Order in charts, from the WSJ.

- Also from the WSJ, have epic housing booms met their match in Australia, Canada and New Zealand?

- An Economist magazine briefing argues that the world needs to face up to the fact that it will miss the 1.5C climate target.

- From late last month, the UN Environment Programme (UNEP)’s Emissions Gap Report 2022. According to the UNEP, updated national pledges since COP26 make a negligible difference to predicted 2030 emissions. Policies currently in place point to a 2.8C rise by end-Century and the implementation of current pledges will only reduce this to a 2.4C-2.6C rise.

- Three priorities for COP27 from the IMF’s Managing Director: Net zero emissions by 2050, more action and support for adaption, and more effort on climate finance.

- Also from the IMF, evidence on electoral cycles in tax reforms. Unsurprisingly, the data show that governments tend to avoid announcing tax reforms during the months running up to elections, but become more likely to announce them in the first few months following elections. Relatively lower institutional quality is correlated with a pre-election decrease in the likelihood of reform.

- An OECD report on Pricing Greenhouse Gas Emissions. In 2021, more than 40 per cent of emissions were covered by carbon prices, up from 32 per cent in 2018. Carbon prices increased in 47 of the 71 countries covered in the report and average carbon prices from emissions trading systems and carbon taxes have more than doubled to reach four euros per tonne over 2018-2021 period. According to the OECD, a mid-range estimate of carbon prices required by 2030 would be 120 euros per tonne.

- Proxy power to the people?

- How shipping costs drive global inflation. Shocks to ocean freight costs have similar inflationary effects as shocks to global oil and food prices but are more persistent.

- Dario Perkins (TS Lombard) reckons that inflation is the only socially-acceptable way out of our current predicament for most democratic societies.

- WFH and the office real estate apocalypse (US data).

- According to Noah Smith, macroeconomics is still in its infancy.

- Macro Musings podcast interview with Megan Greene on the recent market turmoil in the UK.

- Ezra Klein talks to Brad DeLong on how inflation destroys governments.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content