In a quiet week for Australian data, the domestic economic news focused on the release of the 2023 Intergenerational Report (IGR).

One of the purposes of the new IGR is to consider the impact of some of the new powerful forces set to shape the Australian economy over coming decades including technological change and geopolitical fragmentation. It also takes into account some old favourites including the ageing population which was considered back in the very first IGR in 2002. Despite some important changes, however, this year’s analysis still came with a familiar message: that without a significant upgrade to our current productivity performance, Australia’s growth performance over the next 40 years is likely to be markedly weaker than that seen over the previous 40 years.

As well as providing a bit more detail on IGR 2023 below, we also consider some of the drivers and implications of the recent tumble in the Australian dollar.

The 2023 Intergenerational Report

This week brought the publication of the 2023 Intergenerational Report (IGR), the sixth in the series. The first IGR was published in 2002 and was intended to assess the long-term sustainability of Commonwealth finances, by examining the combined impact of current policy settings and trends on the budget over a 40-year time frame. In the original IGR, the focus was on the impact of slowing population growth and population ageing. For IGR 2023, the five key forces considered, and their consequences for Australia’s changing industrial base, are:

- Population ageing

- Technological and digital transformation

- Climate change and the net zero transmission

- Rising demand for care and support services

- Geopolitical risk and fragmentation

These IGR 2023 projects will see real GDP growth for the Australian economy and run at an average annual rate of 2.2 per cent over the next 40 years. That’s down 0.9 percentage points from the 3.1 per cent average rate recorded over the previous four decades. (For some contemporary context, annual real GDP growth was a strong 3.6 per cent in post-COVID 2021-22 but had slowed to 2.3 per cent by the March quarter of this year and is set to slower further as the lagged impact of RBA tightening intensifies).

Sitting behind that projected downshift in economic performance are key assumptions around the ‘three Ps’ of productivity, population, and participation.

- The 2023 IGR assumes that future annual productivity growth will average 1.2 per cent, in line with the average over the past 20 years. That’s below the 2021 IGR estimate of 1.5 per cent, which was based on the then 30-year average. The decision to use the lower 20-year average for productivity growth places more weight on recent productivity headwinds including the structural shift towards services industries and the declining impact of previous economic reforms. (For comparison, labour productivity rose by 1.1 per cent in 2021-22 but according to the most recent quarterly data, fell 4.6 per cent over the year to the March quarter 2023).

- The average annual rate of population growth is projected to slow to 1.1 per cent over the next 40 years, down from 1.4 per cent over the past 40 years. That would see Australia’s population reach 40.5 million in 2062-63. That population will also be older. By 2062-63, the share of the population aged 15-64 is projected to have fallen by 3.5 percentage points, while the share aged 65 and above is projected to have risen by 6.1 percentage points.

- An ageing population is expected to lead to a gradual decline in the share of people in the workforce, with the participation rate projected to fall from 66.6 per cent in 2022-23 to 63.8 per cent by 2062-63.

One other point worth noting. In recent decades, growth in income per person has been boosted by big price gains for some of the key commodities Australia exports, which in turn propelled our terms of trade to record highs. That, in turn, allowed for a positive gap between growth in real gross national income (GNI) per head and growth in real GDP per capita. The 2023 IGR assumes that commodity prices and the terms of trade will decline and then stabilise at a lower long-term level, ceasing to contribute to growth in real incomes per person, which will then grow roughly in line with real GDP per person. The annual growth of real GNI per capita over the next 40 years is projected to be just one per cent, down on the 2.1 per cent growth we enjoyed over the previous 40 years.

The implication of these changes for fiscal sustainability is a future of long-term budget deficits, which, after narrowing across the medium term, are then projected to widen from the 2040s onwards due to rising spending pressures. Put differently, while government payments as a share of GDP are projected to increase by 3.8 percentage points (from 24.8 per cent now to 28.6 per cent in 2062-63) total government receipts are projected to rise from 25 per cent of GDP now to 26.3 per cent of GDP in 2033-34 but then fall back to 26 per cent of GDP by 2062-63.

On the spending side of the government accounts, the IGR highlights five main drivers: health, aged care, the National Disability Insurance Scheme, defence, and debt interest payments. Collectively, these five drivers are projected to rise from approximately one-third of all current government spending to around one-half by 2062-63. Demographic ageing alone is expected to drive around 40 per cent of the projected rise in total government spending over this period. On the revenue side, the IGR assumes that tax receipts as a share of GDP will be constant over the long run, at 24.4 per cent from 2033-34 onward, although it also cautions on significant pressures on the economy’s revenue base over the same period.

Some relatively good news in the current IGR is that a stronger starting fiscal position means that gross debt to GDP is only projected to rise to 32.1 per cent of GDP by 2062-63, after having first fallen to 22.5 per cent by 2048-48. That is a lower national debt burden than projected in IGR 2021.

According to the Treasurer, the government’s ‘big, broad and ambitious productivity agenda’ in response to the projections set out in the IGR is focused on five pillars: (1) building economic dynamism and resilience by upgrading institutions, promoting innovation and boosting competition; (2) investing in data and digital infrastructure and helping more businesses adopt new technologies; (3) building a more skilled and adaptable workforce; (4) creating a more sustainable and productive care economy; and (5) powering the net zero transformation.

We talk more about the IGR including whether governments can really do much about productivity growth, how to think about the impact of ‘economic reform’ and the perils of long-term projections in this week’s Dismal Science podcast.

The sliding Australian dollar

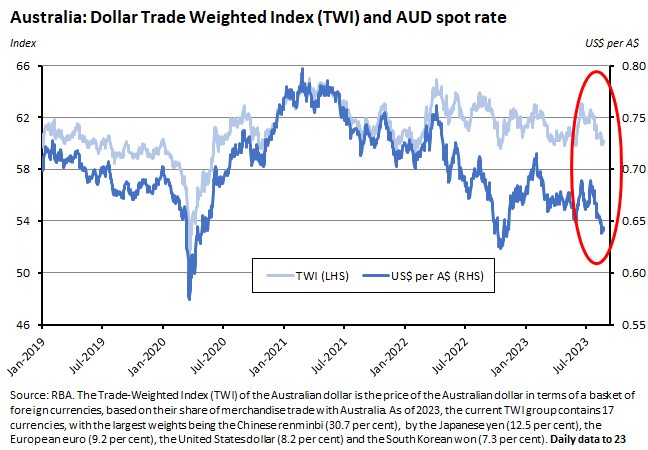

This week also brought a renewed focus on the sliding Australian dollar (AUD), which at the time of writing had slipped to about US$0.64 after having fallen briefly below that rate earlier in the week. The AUD started this year at around US$0.68 and had briefly climbed to above US$0.71 in late January and early February, so the depreciation from that earlier peak is close to ten per cent. Some market analysts are now suggesting the currency could even fall below US$0.60 later this year – a level last reached in the early days of the pandemic.

The AUD’s decline on a trade-weighted basis has been more moderate than its fall against the US dollar, but it is still notable. The TWI stood at an index level of around 61 at the start of this year, had climbed to around 63 in late February and had returned to that level again in mid-June. In contrast, at the time of writing, the TWI had eased to around 60, representing a peak-to-trough decline of more than four per cent.

In recent years, the two key fundamental drivers of the exchange rate have been differences between the level of interest rates here in Australia compared to the level of rates in other major advanced economies (the interest rate differential) and Australia’s terms of trade. Both drivers have been at work this year.

The large fall in the bilateral exchange rate against the US dollar points to the fact that a significant part of the story is greenback strength. Still-robust US growth in the face of tighter monetary policy has prompted markets to push back their estimates of the likely timing of any US Fed rate cut and instead grapple with the likelihood that US interest rates will have to stay higher for longer. (Note that other major implications of this shift have included a dramatic sell-off in the US government bond market as the yield on US 10-year Treasuries hit a 16-year high earlier this week as well as a parallel slump in global equity markets.) In contrast, the Australian interest rate story in recent weeks has involved markets becoming increasingly confident that the RBA is pretty much done in terms of rate hikes. The implication of these two diverging interest rate views is the prospect of a large and persistent policy rate ‘gap’ between the US and Australia.

The other big global driver of the AUD has been the weak performance of the Chinese economy, which has been flirting with deflation, along with the failure of Beijing to deliver a convincing policy response. Sans the traditional infrastructure-heavy stimulus package from the Chinese authorities, means less demand for some of the key commodities (iron ore, LNG) that dominate Australia’s export mix resulting in a lower level for our terms of trade.

The current bout of AUD weakness complicates the RBA’s battle against inflation, as changes in the exchange rate have both direct and indirect effects on the economy. The direct effects of a depreciation in the exchange rate are the consequent shifts in the relative prices of Australian goods and services, which will become cheaper in foreign currency terms, making Australian exporting and import-competing producers more competitive. The indirect effects follow from the implications of those relative price changes for economic activity and inflation and are likely to include increased demand for Australian tradable goods and services, lower demand for imports, and – via the increase in national income from greater net exports – an increase in demand for Australian non-tradable goods and services. In other words, overall a depreciation is likely to boost activity. At the same time, however, it will also boost inflation.

First, a weaker AUD implies higher prices for imported goods and services. The pass-through to consumer prices from an exchange rate depreciation can be split into two stages: the first-stage pass-through from a fall in the currency to Australian dollar import prices, and the second-stage pass-through from import prices to consumer prices. Previous RBA research has found that the first stage pass-though is large and rapid for foreign-currency invoiced imports but much lower for imports invoiced in Australian dollars (according to the ABS, in 2020-21, about 53 per cent of Australian merchandise imports were invoiced in US dollars, 32 per cent in Australian dollars, and less than eight per cent in euros).

Second, the increased demand for Australian production (plus the accompanying increase in employment and wages) could also push up Australian inflation. This will particularly be the case when there is little spare capacity in the economy.

The RBA’s models suggest that when considering the impact of a depreciation on the inflation rate, the TWI is the exchange rate to watch and as noted above, the fall in the TWI has been more modest than decline in the AUD against the US dollar. According to the RBA’s MAcroeconomic Relationships for Targeting INflation (MARTIN) Model, a transitory 10 per cent real depreciation of the TWI would only push up inflation by about 0.3 percentage points (as well as lift the level of GDP by around one per cent after one to two years and lower the unemployment rate by 0.4 percentage points).

Finally, there is some evidence from recent consumer confidence readings (see below) that the depreciation of the AUD may also be denting household sentiment via its impact on higher petrol prices.

What else happened on the Australian data front this week?

The Flash Australia Composite PMI Output Index fell to a 19-month low in August, dropping from a reading of 48.2 in July to 47.1 this month, a result that indicated ‘a solid and accelerated reduction in private sector activity.’ Business activity has now fallen for a fourth time in the first eight months of the year, with the rate of decline in August the quickest reported since January 2022. The decline in activity is being led by the services sector, with the Flash Australia Services PMI Business Activity Index falling to a 19-month low reading of 46.7. The services sector also reported its first decline in new orders in five months, with respondents citing the impact of tightening financial conditions and cost of living pressures. The Flash Australia Manufacturing PMI Output Index indicated a slower pace of decline in the manufacturing sector, with the PMI slipping to a two-month low of 49.5. Despite the decline in activity, business confidence among private sector firms rose to its highest level in seven months, with both manufacturing and services businesses reporting a rise in optimism. That confidence was also seen in an increase in the employment index, which is now back above 50 and in positive territory. Finally, overall price pressures eased somewhat in August as services firms reported slower increase in input costs. This was enough to offset a pickup in the pace of manufacturing input cost inflation due to worsening supply conditions.

The ANZ-Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence index fell 2.4 points to a reading of 75.8 in the week ending 20 August, after having previously risen by 3.2 points in the week ending 13 August. Four of the five subindices (current and future financial conditions, current and future economic conditions) declined although time to buy a major household item edged up by 0.2 points. ANZ suggested the drop in confidence could reflect the recent weakness in the Australian dollar and the consequent rise in retail petrol prices. The accompanying measure of weekly inflation expectations also rose 0.3 percentage points to 5.5 per cent.

According to the ABS, there were 2,589,873 actively trading businesses in Australia as of 30 June 2023, up 0.8 per cent or 19,973 businesses from June 2022. The firm entry rate was 15.8 per cent while the exit rate was 15 per cent. The industries that saw the largest net increase in the number of businesses were Health care and social assistance, Transport, postal and warehousing, and Professional, scientific and technical services. The largest net decrease in numbers was for retail trade.

Other things to note . . .

- Treasurer Jim Chalmers’ opinion piece accompanying this week’s release of the 2023 Intergenerational Report argues that we need to ‘turn around Australia’s longstanding sluggish productivity performance’ by meeting ‘the big structural changes in the economy like the impact of climate change, growth in the care economy and the spread of digital technology.’

- A media release from Treasurer Chalmers and Assistance Minister Andrew Leigh announcing a review of Australia’s competition policy settings. The review will be conducted by a Competition Taskforce and will consider ‘competition laws, policies and institutions to ensure they remain fit for purpose, with a focus on reforms that would increase productivity, reduce the cost of living and boost wages.’ Initial issues to be considered include the ACCC’s recent proposals regarding merger reform, the treatment of non-compete and related clauses and options for coordinating reform with the states and territories.

- A new economic report from the Business Council of Australia (BCA), Seize the moment.

- Against picking winners: outgoing Productivity Commission chair Michael Brennan in the AFR. Related, Brennan’s address to the National Press Club on Productivity, public policy and challenges associated with Closing the Gap.

- John Hawkins on Australia’s cost of living crisis.

- Grattan Institute submission on seizing Australia’s hydrogen opportunities.

- RBA media release and report (pdf) on a research project exploring potential use cases for a central bank digital currency (CBDC) in Australia. The report identifies four key themes: (1) enabling ‘smarter’ or more complex payment arrangements; (2) supporting innovation in financial and other asset markets; (3) promoting innovation in private digital money; and (4) enhancing resilience and inclusion in the digital economy by providing households and businesses with alternative ways to make payments or access money without requiring a commercial bank account.

- In the FT, Chris Giles argues that recent talk of the end of inflation and soft landings is premature. AFR version.

- The WSJ asks now that China’s 40-year boom is over, what comes next?

- Related, a couple of weeks back I linked to Adam Posen on the end of China’s economic miracle. Nicholas Lardy, who is a colleague of Posen’s at the Peterson Institute, is more sanguine on China’s growth prospects.

- An ASPI Brief on China’s property sector.

- This piece from Nature offers suggestions on how to speed up scientific progress. According to the authors, academic scientists should: spend more time working in government to understand how science policy works; look for ways to collaborate with think tanks; and work to change academic norms to value use-inspired research.

- Central banks at the crossroads: the BIS Deputy General Manager argues that central banks and central bankers face five major forks in the road: the re-emergence of inflation (including a future of more cost-push factors), climate change (with risks to price and financial stability and the challenge of radical uncertainty), inequality (higher inequality tends to decrease the efficacy of monetary policy), digital financial innovation (potentially a double-edged sword for policymakers) and artificial intelligence (with a possible challenge to the ‘art’ of central banking).

- The Cato Institute says Argentina should dollarise. Others argue that dollarisation is not the answer to Argentina’s economic problems. This older FT piece (also mentioned on this week’s Dismal Science podcast) looks at the lessons from Ecuador’s dollarisation experience.

- This assessment of minimum wages in times of high inflation by two OECD economists reckons that they have proved to a be useful policy instrument in protecting the most vulnerable workers from higher prices, and that there appears to be little evidence that they risk a wage-price spiral.

- Brookings surveyed 285 executives, academics and researchers in the global technology industry for their views on technology competition between nations. On balance, they see the future of the global technology industry as ‘bifurcated and de-risked, with many firms continuing to serve both the US and Chinese technological systems – even as these two ecosystems grow more separate and distinct.’

- An explainer for the price cap on Russian oil.

- Joshu Gans with an updated assessment of life among the Econ tribe.

- Review of a new biography of Spinoza, ‘the master thinker to whom we owe freedom, democracy and modernism itself.’

- The macro musings podcast talks to Zac Gross on the past, present and future of Australian monetary policy.

- A podcast celebrating the 20th anniversary of the Marginal Revolution economics blog.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content