Phil Ruthven examines the key cultural and political divides across the globe and the progress being made towards a less divisive world

The world is shrinking. Modern and fast communication, together with automated interpretation of different languages on the internet is seeing to that.

But there are still barriers to better understanding across the world’s 7.3 billion population, and some of these differences are scary, notably terrorism.

The main barriers to a more peaceful and wider-trading society and economy are language, religion, politics, standard of living, climate and culture. A numerical look at the dividing factors across the world’s 230 nations and principalities can provide some perspective.

The spoken word

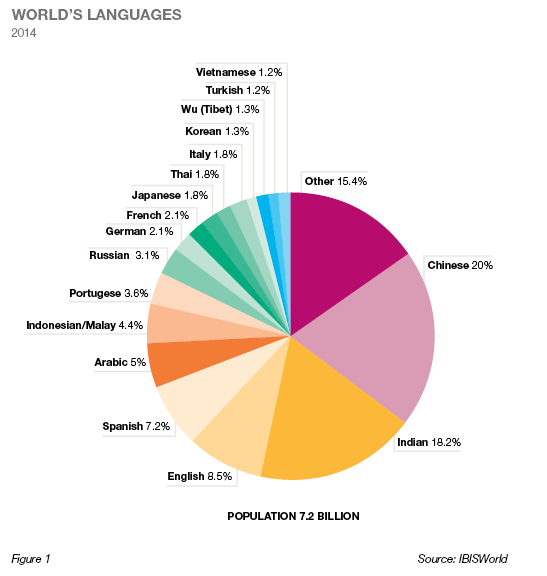

Language is a good place to start. The first figure shows the diversity of the spoken word, whether the result of the Tower of Babel as claimed in the Book of Genesis, or in other origins.

As can be seen in the chart, Chinese and Indian languages are the top two first or second languages; perhaps not surprising given these are the world’s two most populated nations. Yet English is the most widely spoken as either an official language or as one of the languages spoken across 188 countries, accounting for over 80 per cent of all nations.

While language can be a barrier to the integration of societies, these days it is not as problematic as it once was due to the aforementioned revolution in communications.

A greater divide

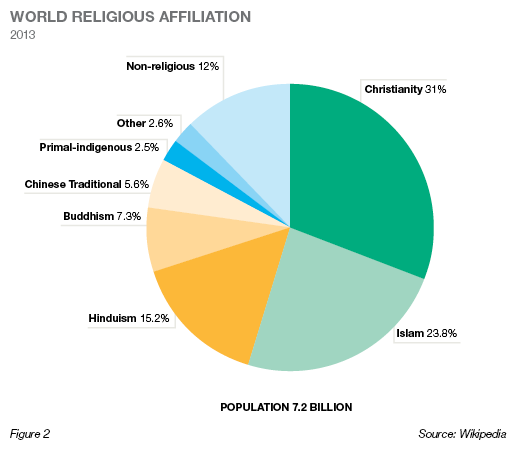

Religion, on the other hand, is more divisive. This can be seen by the Crusades of the early second millennium and other “holy wars” that have occurred throughout the ages. The founders of the hundreds of religions, for the most part, were well intentioned and typically, pacifists. It is just a shame that some claimed inheritors have chosen to fanaticise the original teachings. Terrorism, using religion as a justification, has been able to gain traction even in an advancing world economy and society such as exists today, although not so surprising when divisions of wealth and the absence of true democracy still prevail in some parts of the world.

The second figure shows the religious division extant in 2014. Many of the major religions’ leaders and oligarchs have exercised hegemony over their followers and outsiders across millenniums. Those that have done so are basically witch doctors and have often done far more harm than good.

The witch doctors, sadly, are alive and well in this new century too. As suggested earlier, political ideologies, oppression and poverty are all contributors to unrest, unhappiness, rebellion and fanaticism.

Political landscape

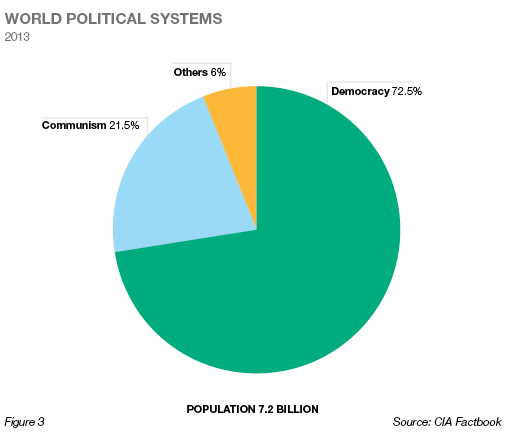

In the third figure we see the world’s political systems. At first sight, we could be cheered by the dominance of “democracy” experienced by over 70 per cent of the world’s population. However, this is misleading. A true and fair democracy is expensive. It requires a standard of living of more than $25,000 per capita to ensure fair elections, an adequate and honest judiciary system, and reasonably corrupt-free military and police forces via taxation.

It also requires the tax capability to provide a measure of egalitarianism via support to the unemployed, aged, sick and illiterate members of society.Australia, as an advanced economy, derives taxes to do all the above, spending over $20,000 or 30 per cent of its standard of living ($67,000 per capita) this year. So, our taxes are higher than the entire standard of living of most developing economies who battle to generate enough taxes to support democracy.

Therefore, we have a long way to go before democracy can actually work in poor and developing economies. Indeed, democracy achieved too early in a developing economy can arguably be worse than a benevolent “guided democracy” or even a competent benevolent dictatorship. Sadly, a number of so-called democracies around the world are headed by incompetent and greedy, if not malevolent, dictators.

Though communism is on the wane, it still accounts for over a fifth of the world population, mainly in China. With a standard of living of just $8,000 per capita, China is in no position to be able yet to provide the egalitarianism we now take for granted in the developed world. One day it will, but not for some decades. All it can do is gradually provide more benefits, more freedom and openness to its citizens.

Quality of life

Looking at standards of living across the globe, it is sobering to know the world average is around $12,000 per capita, compared with Australia’s $67,000 per capita.

Further, the rich nations of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), control 64 per cent of the world’s global domestic product (GDP) with less than a fifth of the world’s population. Their average standard of living is around $36,000 per capita, ranging from $16,000 per capita in Turkey and Mexico to $67,000 per capita in Australia and $80,000 per capita in Luxembourg.

This leaves over 80 per cent of the world in the other 190-plus nations with an average standard of living of just $5,900 per capita.

This is a serious division in the world, demanding much tolerance, knowledge transfer and generosity by the rich nations for all the right reasons; and to avoid the damaging risks of envy, rebellion and terrorism to those that have already made it.

The world has had many wealth divisions over thousands of years. Sometimes these have arisen via the establishment of empires such as the Roman, Persian, Ottoman and British empires; and, one could perhaps add the current “American Era” (arguably a more benign power). Interestingly, the British Empire was built over a period of 150 years with a GDP of just 2 per cent per annum growth, followed by the rise of the US over 100 years at 3.5 per cent per annum growth in GDP.

This makes the current growth of China extraordinary. With over 8 per cent per annum growth during the past half century, China is on its way to becoming the world’s largest economy within several years, especially with a population of 1.4 billion compared with 40 million in the UK and 70 million in the US when they began their march to supremacy.

Of further significance is the old East-West divide. This year, for the first time, the East has matched the economic power of the West; now 50/50 in terms of GDP in purchasing-power-parity terms. The times are a-changing, as is said.

A more encouraging development over the past five decades, since the end of the industrial age in the West and most of the OECD, is the emergence of economic regions as depicted in the final figure.

Gradually, during this new era, extending from the mid-1960s to the middle of the 21st century, the world’s 230 nations are coalescing into eight regions. This is bringing more peace, prosperity, neighbourliness, trade and social interchange via travel than the world has ever seen. The Middle East may take longer than other regions due to intense racial and long-standing religious animosity, and Africa is taking a long time to emerge from poverty, pestilence and corrupt leadership.

So, not yet a world without divisions and differences, but progress all the same.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content